The Oak Island Mystery

Just off the rugged southeast shore of Nova Scotia lies a tiny island fashioned somewhat like a question mark. The shape is appropriate, for little Oak Island is the scene of a baffling whodunit that has defied solution for over two centuries. Here, ever since 1795—not long after pirates prowled the Atlantic coast and left glittering legends of buried gold in their wake—people have been trying to find out what lies at the bottom of a mysterious shaft dubbed, hopefully, the “Money Pit.”

Using picks and shovels, divining rods and drilling rigs, treasure hunters poured about $1.5 million into the Money Pit. Despite more than 20 attempts, no one has yet reached bottom: each time a digging crew has seemed close to success, torrents of water have suddenly surged into the shaft to drown their hopes. Although it’s now known that the Money Pit is protected by an ingenious system of man-made flood tunnels that use the sea as a watchdog, no one knows who dug the pit, or why.

One legend makes the pit the hiding place for the plunder of Captain Kidd, who was hanged for piracy in 1701. Other theories favour the booty of Blackbeard and Henry Morgan, both notorious buccaneers; or the French crown jewels that Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were said to be carrying when they attempted to flee during the French Revolution; or Shakespeare’s missing manuscripts. Whatever the pit may contain, few other treasures have been sought so avidly.

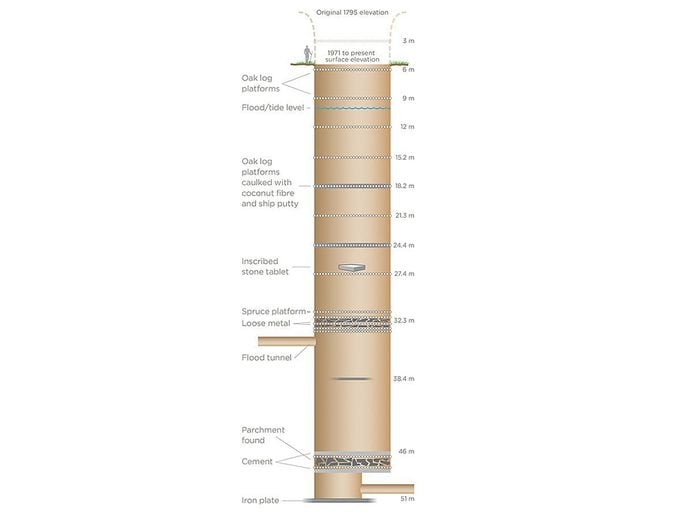

Inside the Oak Island “Money Pit”

The long parade of searchers began one day 200 years ago, when Daniel McGinnis, a 16-year-old from Chester, Nova Scotia, paddled over to uninhabited Oak Island to hunt for game. On a knoll at one end of the island, he noticed an odd depression. Above it, on a sawed-off tree limb, hung an old ship’s block and tackle. McGinnis’s heart raced, for in the nearby port of LaHave, once a lair for pirates preying on New England shipping, he had heard many legends of buried treasure.

The next day, he came back with two other boys, Anthony Vaughan and John Smith, and began digging. Three metres down they hit a platform of aged oak logs; at six metres, another; at nine metres, a third. In the flinty clay walls of the shaft, they could still see the marks of pickaxes. As the work grew harder, they sought help. But no one else would go near Oak Island. It was said to be haunted by the ghosts of two fishermen who vanished there in 1720 while investigating strange lights. So the boys gave up, temporarily. (Check out more chilling tales of Canada’s most haunted places.)

Later, McGinnis and Smith settled on the island. In 1803, intrigued by their tale, a wealthy Nova Scotian named Simeon Lynds joined them in forming a treasure company. Along with the oak tiers, they uncovered layers of tropical coconut fibre, charcoal and ship’s putty, plus a stone cut with curious symbols. At 28 metres, the diggers drove a crowbar 1.5 metres deeper and struck a solid mass. Lynds felt sure that it was a treasure chest.

But next morning he was amazed to find 18 metres of water in the pit. Weeks of bailing proved fruitless; the water level remained constant. Lynds assumed that this was due to an underground freshwater spring. The next year, his hired miners dug 33 metres down, off to one side of the Money Pit, then began burrowing toward it. When they were only a metre from it, gallons of water burst through. As they scrambled for their lives, the shaft quickly filled to the same depth as the Money Pit.

Beaten and almost broke, Lynds gave up. McGinnis died. But Vaughan and Smith never lost hope. In 1849, they took another stab at the Money Pit, with a syndicate from Truro, Nova Scotia. The results were dramatic.

Layer After Layer

At 30 metres down, just where the crowbar had hit a solid mass in 1803 a horse-driven pod auger (which picked up a sample of anything it passed through) pierced a spruce platform. After dropping through an empty space, it cut into 10 centimetres of oak, 59 centimetres of metal pieces, eight of oak, 22 of loose metal again, 10 more centimetres of oak and spruce and then into deep clay. To the drillers, this suggested an exciting prospect—a vault containing two chests, one atop the other and laden with treasure, perhaps gold coins or jewels. Moreover, the auger brought up something tantalizing: three links of a gold chain.

A second 34-metre shaft was dug in 1850. It also flooded. But this time a workman fell in and came up sputtering, “Salt water!” Then someone noticed that the water in the pits rose and fell like the tide. This discovery jogged Anthony Vaughan’s memory: years before, he had seen water gushing down the beach at Smith’s Cove—158 metres from the Money Pit—at low tide.

The treasure hunters stripped the sandy beach, looking for a hidden inlet of the sea. Under the sand, to their astonishment, they found tons of coconut fibre and eel grass on a stone floor that stretched 47 metres wide, the full distance between the high- and low-tide marks. More digging uncovered more surprises: five rock-walled box drains slanted in from the sea and dropped 21 metres straight down, converging on a line aimed at the Money Pit.

In effect, the beach acted as a gigantic sponge to soak up tidewater and filter it into a conduit. This conduit dropped 21 metres straight down, later exploration proved, then sloped back to a point deep in the Money Pit—all of it filled with loose rock to prevent erosion. This brilliant baffle was no natural obstacle; it was the work of a genius. As diggers neared the cache at 30 metres, they had unwittingly lessened the pressure of earth that plugged the mouth of the conduit.

Undeterred, the Truro crew built a cofferdam to hold back the sea. The sea promptly wrecked it. Next they dug 36 metres down and burrowed under the Money Pit. But while the diggers were at dinner, the bottom of the pit collapsed into the tunnel, then dropped even further—into a mysteriously empty space.

Don’t miss these haunting tales of Canada’s most famous shipwrecks.

The Curse of Oak Island

Though the Truro syndicate lost $40,000, its discoveries excited wide interest in Oak Island. A series of costly expeditions followed, all dogged by bad luck. One outfit gave up after a huge steam pump exploded, killing a man. In 1893, almost a century after the dig began, still another syndicate was organized, this time by Frederick Blair, a Nova Scotia businessman who was to spend almost 60 years trying to solve the mystery.

Blair and his partners resorted to core drilling. At 47 metres—the deepest yet—their bit chewed into 18 centimetres of cement, 13 centimetres of oak, 81 centimetres of metal pieces, then more oak and cement. Finally, at 51 metres, it rattled against impenetrable iron.

To Blair, this indicated a treasure chest encased in primitive concrete, larger and buried deeper than the ones drilled through in 1850. This time, along with flecks of gold, the bit brought up a tiny scrap of parchment bearing the letters vi, written with a quill pen and India ink, according to analysts in Boston. “That’s more convincing than a few doubloons would be,” Blair claimed. “Either a treasure of immense value or historical documents are at the bottom of that pit.” But the syndicate never found out. After spending more than $100,000, it folded.

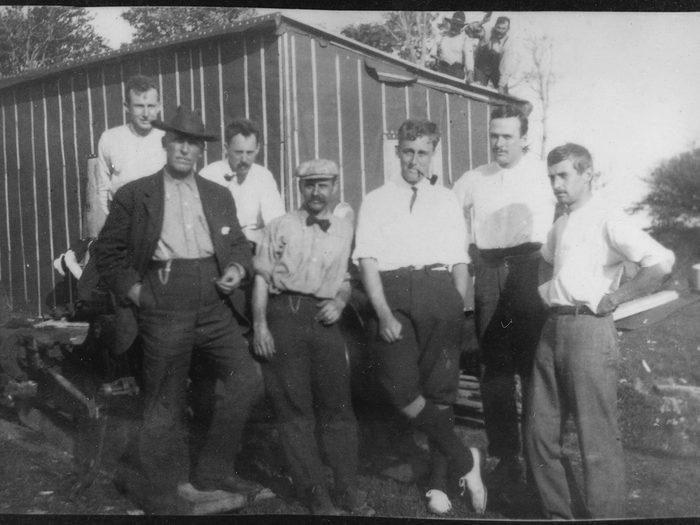

Only Blair carried on. He secured treasure-trove rights to the island for 40 years, then offered to lease them for a share in any bonanza that might be found. The first taker was engineer Harry Bowdoin, of New York. With several prominent backers looking on—including a young lawyer named Franklin D. Roosevelt (above)—Bowdoin dug and drilled in 1909, to no avail. Then he wrote a magazine article for Collier’s, claiming that there had never been any treasure on Oak Island anyway.

Next came syndicates from Wisconsin, Rochester, N.Y., and Newark, N.J. All failed. In 1931, William Chappell, of Sydney, Nova Scotia, sank $30,000 into the Money Pit. Then the Depression made him quit. Chappell was followed in 1936 by Gilbert Hedden, a New Jersey millionaire, who spent $100,000 more. Hedden ran submarine power lines from the mainland to drive high-speed pumps and hired a Pennsylvania mining firm to clear the 51-metre shaft. Again, nothing.

At the time of Blair’s death in 1951, Oak Island and its treasure rights were acquired by William Chappell’s son, Mel, who had worked with his father’s expedition in 1931. Mel Chappell spent $25,000 on one excavation, which quickly became a small lake, then leased portions of his rights to a series of other fortune hunters, the latest being Robert Restall, of Hamilton, Ontario.

A 59-year-old steelworker, Restall quit his $150-a-week job in 1959 and moved to Oak Island with his wife, Mildred, and their sons, Bobbie and Rickey, then 24 and 14. The Restalls have lived there ever since, in a two-room cabin beside the Money Pit, a caved-in crater filled with sludge and rotting timbers. Restall has managed to clear a 47-metre shaft sunk in the 1930s. He has added eight holes, eight metres deep, trying to intercept the flood tunnels that have foiled all previous searches.

To finance his hunt, Restall has already sold about half of his half-interest in any treasure to friends and interested strangers, who have written from as far away as Texas. In all, including savings and five years of hard labour, Restall figures that his quest for Oak Island’s elusive hoard cost almost $100,000. Yet all he has to show for it so far are an olive-coloured stone chiselled with the date “1704,” which he found in one of the holes, and a profound respect for whoever designed the Money Pit. “That man,” he says, “was one hell a lot smarter than anyone who has come here since.”

Is there really a treasure at the bottom of the Money Pit? As petroleum engineer George Greene put it in 1955, after drilling on Oak Island for a syndicate of Texas oilmen, “Someone went to a lot of trouble to bury something here. And unless he was the greatest practical joker of all time, it must have been well worth the effort.”

Take a look back at Canada’s most baffling cold cases.

What Lies Beneath: A Timeline of Oak Island’s Modern Day Treasure Hunters

1965: Robert Restall’s six-year hunt for the Oak Island treasure comes to a tragic halt when, while checking on an eight-metre shaft, he is overcome by fumes and topples to the water-filled bottom. His son, Bobbie, along with helpers Carl Graeser and Cyril Hiltz, dash into the pit to help, but all three men also lose consciousness and drown. Probable cause of death: carbon monoxide from the gasoline water pumps.

1971: Triton Alliance Limited, a treasure-hunting group formed three years earlier, deepens one of the most promising boreholes—called 10X—to 70 metres. An underwater camera brings back grainy images of a cavity carved out of bedrock and, within the stone chamber, a severed hand, a corpse and several treasure chests. Excited by the footage, Triton launches 10 diving expeditions. No treasure is found.

1983: Triton Alliance sues ornery local treasure-seeker Fred Nolan, contesting his ownership of seven lots and demanding access to the island’s only causeway, which Nolan was then blocking. Four years later, the courts rule Nolan can keep the lots but order him to open up causeway access. Alas, the costly court battle, combined with the 1987 stock market crash, spooks investors and forestalls all Money Pit activity for nearly a decade.

2014: Treasure buffs Rick and Marty Lagina, two Michigan brothers who now own most of Oak Island, inspire the History Channel to build a reality show around their efforts to excavate the area.

© 1964 the Rotary International, The Rotarian (January 1965). rotary.org

Intrigued by the Oak Island mystery? Explore 15 more fascinating unsolved mysteries across Canada.