Reader’s Digest Canada: In your memoir, All We Leave Behind, you describe reporting from Pakistan early in your career. Three decades later, you’re the co-host of CBC’s As It Happens. How have things changed for female journalists in the intervening years?

Carol Off: When I started out, it was unusual to meet women in the field. Now there are many of us. I remember a turning point: going back and forth between Jordan and Israel during the Gulf War in early 1991. This young male journalist from Ireland started hanging around with me, which was surprising—the men were cliquish. He said, “You get through the checkpoints easier than anybody.”

That access is part of why you wrote this book, which centres on the Aryubwals, an Afghan family. Their lives were in danger in part because the father spoke out against local warlords in a documentary you produced in 2002. You’re candid about your struggle to separate yourself from this story.

I still think you have to keep that distance as best you can, but now I have a stronger sense of my responsibilities in protecting the lives of others.

You helped the Aryubwals come to Canada, which took over a decade. What did you learn in the process?

They came in as a government-sponsored family, but if I hadn’t been helping them, I don’t know how they could have survived. After they arrived in Hamilton in 2015, they were sent to a shelter to get processed; we met refugees there who didn’t have anyone to advocate for them. What they went through was appalling. I think the government should expand the private sponsorship program tenfold. It doesn’t just benefit those who’ve found places to live; it’s transformative for the communities themselves.

The family arrived two years ago. How has the transition been?

The Aryubwals are doing fine. It’s difficult for them to find the jobs they want, to find housing they want. I keep saying, “These are normal problems.” They agree: these problems are a relief after wondering if you’re going to get killed or abducted.

In the book, you reflect on key events—the U.S.’s involvement in arming mujahedeen in Afghanistan during the Cold War to fight a proxy war with Russia, for example—which led to the current refugee crisis. Are there similar red flags today?

Libya is a failed state because we joined a campaign to take down Muammar Gaddafi, and when he was dead, we said, “You’re on your own.” ISIS is there. Al Qaeda is there. We’re creating failed states all over the place. The biggest victims of terrorism aren’t in Manchester, Boston or Paris. Overwhelmingly, they’re people in Muslim countries who are under attack by their countrymen.

You describe your experience with the Aryubwals as “life changing.” How so?

I have my brothers and sisters. I have a husband, kids, stepkids and grandchildren. But I also have this other family, and I consider them to be part of my family, too. I can’t imagine my life without them. It’s hardly consolation for what I put them through, but it’s just been such an extraordinary friendship.

Next, check out our interview with long-time CBC anchor and host Peter Mansbridge.

Searching for My Birth Mother

It was 1984 and I was a helmet-less six year old, peddling my red bike into Mom’s forbidden territory—across the street. I was in wonder of the new faces, places and houses. Heck, even the weather was different. It was during those times that I knew my life would be about searching. For what, I didn’t know.

It was a few years later that I found out about my adoption. I didn’t quite understand. My parents, who loved and nurtured me, fed me breakfast, lunch and dinner, read me bedtime stories—they weren’t actually my parents? I questioned my friends: “Are your parents actually your real parents?” I would get funny looks, but they all said the same thing. Yes, their parents were their real parents. They were also loved and nurtured. This was unbelievable. I was different. Who was I? I went back to my schoolwork, thinking of those long-ago, forbidden bike rides.

I was a teenager when I came to terms with the secret I was keeping from most people. Was there a stigma attached to someone like me? Was it possible that in this vast universe, there were others like me? Taken in as a baby by two loving human beings who could not have a child of their own. Given up by a woman I had absolutely no clue about. Dreams began to occur about this woman who had the courage to carry me for nine months, only to let me go to complete strangers. She seemed like a ghost, floating around my peripheral vision. Knowing I didn’t look like either my adoptive mom or dad, I began searching the faces of the women I’d see on the street. Green or blue eyes. Red or brown hair. My short stature had me crossing taller women with those features off my list. I loved reading so I looked for women who had a book with them. I searched pews in churches. She was a believer, of that I had no doubt. I wrote poetry and wondered if she, too, was writing in her journal at the same time. Did she also see beauty in words? Were her thoughts and feelings put down on paper as well? Did she roam the aisles of used bookstores? Was she the worst in her math class, too? In my mind, she was just like me.

I hoped against hope. You’ve read or heard those adoption stories that end in horror—guilt trips and angry protests, doors slammed in faces because the hurt was too much.

I began to have a little luck. After submitting requests throughout the years, information from adoption agencies began filling my mailbox. The government was sending out all available information to adoptees as the rules had changed.

Years went by. I received pages of information on my birth mother: how many siblings she had, her medical history, but the one thing that eluded me was a name. How was I to start my search if I didn’t have a name?

Success At Last

In August 2020, I received another letter from the agency. This one was different. There was a name attached to it. I went online and played detective, deducing who was who, cross-referencing surnames and ages, towns and cities. I chose a few people who I thought might give me the greatest chance of finding my birth mother. I stated my name and intent, knowing full well a sensitive subject like this wouldn’t just change my life, but someone else’s, too. I sent the message into cyberspace. The following morning, I received a message. Someone knew my birth mother. The woman who gave me life wanted to connect. As humans, we steel against rejection. As an adopted person, the fear that we’ll be rejected once again, can be an insurmountable feeling.

It turns out, she knew this day was coming. My whole life wasn’t just a footnote in a used book. I was thought of on birthdays and Christmases. Even though other children called her “Mom,” I had a special place in her heart that was all mine. She prayed everyday that her first born would come back to her. Both of us cried tears of joy. Finally, a reunion.

Feeling a Connection

I found myself believing in miracles. Age- old questions were answered. Slowly but surely, a bond started to form. Each time we talked, there was always something new to learn. She preferred the library to the bookstore, where, just like me, she went every week. She read poetry, but didn’t quite understand what the poets tried to convey.

A journal for her thoughts was a constant companion. Her math skills were just as non-existent as mine, so we had both stayed away from numbers. Both of us, generous with our time, thinking of others first. My grey eyes were from her dad, my grandpa.

We had both known that we’d see each other again. It blew my mind that I had manifested all of this from thoughts and dreams as a teenager. Our connection felt familiar. As if we had known each other all along. It seemed that we had been living parallel lives and began seeing ourselves at a deeper level.

Truthfully, such commonalities are not unheard of. Science calls it quantum entanglement. Two different objects, no matter space or time, mirror the same trajectory. The religious would call this a God incident. Any way you explain it, the void in my soul I had felt for so long had been filled. It was amazing. I had been working on this unfinished puzzle my whole life—turns out, the missing pieces were right there the whole time, wondering where I was, too.

Next, read about how this mother-and-son tour of Haida Gwaii became the trip of a lifetime.

IN THE FALL OF 1988, when I was 10 years old, my parents moved us to a bigger house across Peterborough. I was forced to leave the familiarity of St. Paul’s and become “the new kid” at St. Teresa’s: a one hallway school with no gym where the other kids in my Grade 5 class had been together since kindergarten. I struggled to break into the crowd and spent recesses playing hopscotch alone, gazing longingly at the other kids as they traded their Twinkies and Fruit Roll-Ups. I was lonely and desperate to make a friend.

One school day in early December, shortly after the move, I poured myself a bowl of Life cereal and headed to my designated spot at the kitchen table. The radio was tuned to a golden oldies station. The DJs, whose voices were the audio wallpaper of my youth, bantered between songs. “It’s a sad day in the music world,” I heard one of them say. “Mr. Roy Orbison has died.”

Oh no, I thought, how sad, Roy Orbison has died. Wait…who is Roy Orbison? I didn’t have a chance to ask. I had to get to school before the bell.

I was in Mr. Hutchison’s class, but he liked to be called Mr. 83. He used to teach in Japan and his name sounded like the Japanese numbers eight (“hachi”) and three (“san”)—Mr. “Hachi-san.” It seemed pretty clever to this 10-year-old. I think he felt sorry for me because I was struggling to fit in, so he gave me my own nickname, “Meggie McMuffin,” and I loved it. Mr. Hutchison was in my corner.

Every day after the national anthem, Mr. Hutchison would ask if there was anyone we wanted to pray for, and he’d write their names on the chalkboard so we could keep them in our thoughts. That day, Johnny, with the gelled hair, asked us to pray for his grandfather who‘d just had surgery. Emily, with the long ponytail, asked us to pray for her grandmother who had pneumonia. Clare, the intimidating popular girl, asked us to pray for her dog, Sparky, who’d just had his manhood removed.

This was it. This was my chance to fit in! Before I had time to fully think it through, my hand shot into the air, and when Mr. 83 called my name I blurted out, “I’d like to pray for Roy Orbison!”

A hush fell over the room. The other kids looked confused, but Mr. 83 could see the desperation in my eyes. No one had ever been so excited to pray for anyone in the history of the Catholic Church.

“OK, McMuffin, Roy Orbison has been added to the prayer list.” He winked.

I did it! This must be another way we Catholic kids make new friends: you just pray for someone.

I had never met Roy Orbison, nor did I have his album or know who his “Pretty Woman” really was. But I like to think we’ve played an important role in each other’s lives. If there is a heaven, Roy is there because a Grade 5 girl prayed for him.

And because of Roy Orbison, a little girl named Christine came up to me during class and said, “I’m really sorry for your loss. If you’re not busy with the funeral, maybe you can come over and play after school.”

Thanks to Roy and Christine, I was lonely no more.

De-icing with Driveway Salt

Ideally, you’ll sprinkle salt on your driveway before a heavy snowfall. When you’ve missed your window of opportunity, however, it’s best to shovel the driveway before applying salt—starting with a bare driveway will require less de-icer in the long run.

Although driveway salt’s affordable price point makes it an attractive de-icing option, it can damage your lawn or garden. Canadians use about five million tons of rock salt each year, but it can harm plants, contaminate water and, in severe cases, sicken or kill wildlife. You should also keep in mind, according to Scientific American, when temperatures drop below -18° Celsius (zero Fahrenheit), ice can’t be dissolved by salt.

Sand

Sand will increase traction and is more garden-friendly than driveway salt. Just be sure to clean it up properly in the spring, as it can easily clog drains or sewers, and because it absorbs contaminants like oil and chemicals. Gravel is another possible solution.

Other Driveway Salt Alternatives

Though salt remains the most accessible means of de-icing your driveway, other options exist. (You might also consider the pros and cons of heated driveways.) A rule of thumb: The more eco-friendly the product, the higher its cost will be.

Most combine driveway salt with five other common materials:

- Calcium magnesium acetate: CMA is a green alternative that is salt-free and biodegradable. However, it is slow acting and only works in mild temperatures.

- Calcium chloride: It won’t hurt your plants, but it can corrode metal and hurt the tender paws of your pets. Works well in cold weather. Don’t track this into your home since it can leave a residue on carpets and shoes.

- Potassium acetate: It’s not that harmful since it is biodegradable, non-corrosive and non-toxic. But it’s pricey and won’t perform well in extreme cold.

- Magnesium chloride: This salt works well in cold weather but use sparingly because too much will make your pavement wet. Can damage concrete.

- Urea: Also known as carbamide or carbonyl diamide, this de-icer can burn your lawn and garden. Since it’s high in nitrogen it also causes algae bloom in waterways. Should be avoided.

Two Major Considerations When De-Icing Your Driveway

Always keep the minimum effective temperature (MET) of ice melters in mind. If sub-zero temperatures are rare where you live, you don’t need an ice-melter with a MET capacity of -31° C/ -25 ° F.

Use ice melters sparingly; throwing more down won’t melt ice any faster. And don’t shun the greenest method of snow and ice removal: shovelling. De-icers can’t melt through compacted snow or built-up ice, so the less there is, the more effective they’ll be.

Next, find out how to remove snow from your car quickly.

“Three peppers for five dalasis!”

“Get my onions for 10!”

“Hey, pretty lady, come buy my stuff!”

It’s June 2015, and the air in the neighbourhood market in Yundum, The Gambia, is full of dust and exclamation marks as I hurry from one vendor to the next under the hot sun. Around me, sellers have spread their items over corrugated metal and cardboard balanced on wooden platforms: a display of fish in one place, salad greens at another, rice at another still. They flap fans back and forth to keep flies from settling on their goods.

The plan for my family’s meal that day is a stuffed chicken. Covered head to toe in a black niqab, I look like many other women in the market, though I wish for anonymity more than purity. Near the entrance to the market are the two men who have followed me on the 15-minute walk from my mother’s home, and who now watch as I go from vendor to vendor.

I make my way to my destination, a shop that sells cooking oil. Tucked against the perimeter of the market, the store’s corrugated side panel provides a place just out of view of the entrance. As the vendor passes me my oil, I tuck it into the basket at my feet and sneak a look at the entrance. I can’t see the men, making it likely they can’t see me. I know the oil seller will recognize my younger sister, Penda, or mother, Awa, when they come looking for me, and that the basket of food I am abandoning here will be passed on to them.

I duck out the back of the shop to where the taxi drivers gather. I slide into the front seat of the closest car. “I need to go to Banjul,” I tell the driver, handing him 500 dalasis, just over 10 Canadian dollars. I take the SIM card out of my phone and throw it away so I can’t be tracked. My life now depends on me escaping The Gambia.

The pageant

I was 18 and in my first year at Gambia College when I decided to enter a national pageant sponsored by my country’s president, an all-powerful dictator named Yahya Jammeh. The pageant, which was meant to commemorate the coup that brought Jammeh to power, required each contestant to perform, speak on a topic related to improving life in The Gambia—mine was about eradicating poverty—and appear in our traditional tribal costumes. If I won, I was promised a scholarship to study anywhere in the world as my prize. I came second in the first round at my college, which qualified me for the final. Shortly after, in December 2014, I was crowned the winner.

At first, it was exciting. Jimbee, the president’s cousin, became a frequent visitor and caller. She invited me to many public and private meetings with Jammeh. To my shock, however, after almost six months of what I later recognized as grooming, the president proposed. I told him I wasn’t ready, that I was too young for marriage. But he was the most powerful man in our country, and he wasn’t asking me, he was telling me. The choice wasn’t mine; it was his. A few days after my refusal, Jimbee took me to a house that she promised would be mine—if I relented. My answer was still no.

After the visit to “my” house, Jimbee had continued to call me. “Hey, it’s been a while,” she said on one such call, in the casual tone of a friend. My stomach lurched. “There’s an event at the State House on the day before Ramadan starts. You have the crown—you have to come.” It was part of Gamo, a religious celebration of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad, and she said I couldn’t refuse.

I dressed for the event in a gold floor-length dress and draped a scarf over my hair in deference to the religious holiday. Once at the State House, I saw guests gathered in the garden for the ceremony. Jimbee was waiting for me inside. I was led to another room, where she told me to wait before she made her excuses and disappeared.

And then Jammeh was there. I hadn’t seen him since he had asked me to marry him. He radiated impatience, even anger.

“There’s no woman I want that I cannot have,” he said, as he crossed the room toward me. My mind scrambled to find words that might placate him, but before I could speak, he dragged me to a bedroom next door. Terror gripped me as he struck me across the face with the back of his hand.

Then he jammed a needle into my right arm. I started to scream. His hands felt big and leathery as they covered my nose and mouth. I know that I struggled. I know that I begged for help. Eventually, I passed out.

There is no word for rape in my first language, Fula, or in Wolof or Mandinka, the other common languages of The Gambia. This isn’t because it doesn’t happen; it’s because we are supposed to believe it is so rare that no word is necessary. If it does happen, we are not supposed to speak of it.

A missing word isn’t the only barrier. English has the words and women still struggle to speak of rape—and when they do, they often aren’t heard. And so, even as I speak in the language of the West, I struggle: to be clear, to be heard, to be believed. I’m not giving it words for me. I don’t need these words to remember being raped, to feel it. I can’t choose to turn off these words and forget. What happened next is with me always, whether I drape it in words of any language or not.

The escape

It was 3 a.m. by the time I got home. As I passed the curtain that covered the entrance to Mum’s room, she peeked out at me, calling, “It’s late!” That wouldn’t have worried her so much, since Gamo celebrations often continue into the early morning hours. But if she had seen me fully, she would have known something was terribly wrong.

After the house went still, I went into the bathroom and turned on the shower. The water was cold, but I didn’t care. I stayed in bed the whole next day, my body numb, waves of disgust washing over me, thinking of all the things I could have done differently. Why hadn’t I left the country immediately after his proposal? What made me think life was going to just go on? What could I do now?

I couldn’t tell anyone, especially my mother—not because she would blame me, but because she would fight back. She would not be quiet about it. She would tell my father and her family. She would tell her boss at the Ministry of Education. That would be dangerous for us all because President Jammeh wasn’t going to let anyone speak out about it. And she wouldn’t be able to put him on trial or see him jailed. She wouldn’t be able to do anything.

A few days later, Jimbee called, speaking as if nothing had happened: “Hey, girl, how are you? Are you feeling good?” She told me of another event. “All of the pageant-winners will be there. A driver will pick you up.”

It was then that I knew for certain that the rape hadn’t been a one-time thing. Jimbee was going to keep calling me. This was going to be my life. This attack on my body would keep happening.

To the border

To leave, I had to go through Senegal, which surrounds The Gambia on three sides; its fourth faces the Atlantic Ocean. As my taxi approached the ferry terminal in Banjul, where I would cross the river to Barra and then travel to the Senegal border, the smell of rotten fish discarded from boats near the dock filled my nostrils. The entrance area was crowded with cars full of people, trucks jammed with goods and pedestrians lining up for tickets. I was scared but focused: I had come this far.

If the men who had followed me to the market had reported me missing, I reasoned, the Gambia Ports Authority security may have been notified: the ferry was the obvious route. To get on, I’d have to buy a ticket, and they might ask me for identification. If I was caught here, maybe I’d end up in prison. Or worse. The official story would simply be that I’d disappeared. My family would never know.

My gaze swept past the terminal entrance, down toward a section of shore. Small, open fishing boats called pirogues bobbed in the water, and in one, a man with a green net appeared ready to set out. Judging by his facial features, he looked Wolof, which was my mother’s tribe. Perhaps this was the solution to my river-crossing dilemma.

“Hey!” I called in Wolof as I made my way toward him. “Can you help me cross over?” I offered a substantial sum for a single passenger on a small motorboat.

“Okay, okay,” he said. There were no life jackets. For 30 minutes, the small boat slapped across the Gambia River estuary toward the opposite shore, the sun beating down on us. As dangerous as it looked, the tiny boat still felt safer than the ferry. Finally I climbed ashore on the sandy beach close to the Barra terminal. Nearby, private taxis and passenger vans waited for fares. I slid into a taxi, and 15 minutes later, I was at the Gambia-Senegal border.

Into Senegal

I could see the chocolate-brown building that housed the Gambian immigration office, and just beyond it, the metal barricade separating it from the corresponding Senegalese immigration office. So far, I had made three escapes: from the market, across the river and from the river to the border. Now I faced the most daunting barrier of all. Here I would almost certainly be asked for my identification, and if my departure had been noted, border officers would likely already have been alerted to watch for me.

Over to one side, I could see town-trip taxis—the kind you hire individually, rather than piling in with other passengers. I was certain these drivers would have other routes, as well: jungle roads and paths without guards.

I approached one of the drivers. “What would a town trip to the other side cost me?” I asked.

“Ten thousand dalasis,” he said. I felt deflated: it was so much more than I had with me that negotiating wasn’t an option. I thanked him and moved back to my perch by the side of the road.

I had enough money for a bus or shared taxi, but I could see that the passengers in these vehicles were being asked for their papers as they crossed. Still, not every vehicle faced the same scrutiny. I saw that the livestock trucks moved through quickly. Those drivers didn’t even disembark at the crossing; the immigration guards just waved them through.

Nearby, a cattle truck had pulled over to a gas pump. This was my chance, I thought—I could see the driver was Fula. And so as I walked toward him, I slid into a new character: a more mature Fula woman with a dying relative in Senegal and no money to pay for a bus. I told him my tale, pleading for him to take me across. To my relief, he agreed.

Through the grimy windshield, I could see the checkpoint over the cars in front of us. The line seemed to have slowed, with officers checking every cab, every car, every shared vehicle, requesting paperwork for all the passengers. Still they seemed to be letting the trucks pass through with less scrutiny.

“Nakala,” shouted the driver in greeting to an immigration officer. As the word left his mouth, part of me wanted to reach into the air and grab it, suffocate it, but it floated away across the road. The driver waved. “How are you?” he shouted to the officer. My whole body shrank inside the niqab. I could hear my every breath, feel my gut dropping.

“Good, good, you know,” replied the officer with a smile.

And then he waved us through, past a tiny metal barrier and into Senegal. Away from a dictator. Into the unknown.

What next?

On the Senegalese side of the border, I was swamped by relief and regret.

What had I done? I’d escaped, but to what? I’d left behind everything I’d ever known in The Gambia. And I could never go back. Jammeh had been president since before I was born. I couldn’t picture the possibility of anyone other than him in power. Robert Mugabe had ruled Zimbabwe since 1980—he was 91 and still in control. Jammeh was only in his 50s. I might be 40 before I could go home. Or 60. But it was too late to turn back.

Most of my money was spent on taxis and paying the fisherman. I used some of what I had left to buy a cheap SIM card for my phone. With the new card in, I dialed Ahmad Gitteh, a schoolmate who now was studying in Canada. I hadn’t spoken to Gitteh in months, but I knew he might have connections outside The Gambia. In my desperation, I hoped he would help me.

He was confused, but he agreed to text me the name and number of Ebrima Chongan, who had been a deputy inspector of police in 1994, at the time of the coup that put Jammeh in power. Chongan had tried to rally the police to help keep the democratically elected government in place, but Jammeh had Chongan and other police officers arrested and held in prison.

Under Jammeh’s rule, the prison became synonymous with state-sponsored torture and abuse of political prisoners. Chongan was imprisoned for 994 days. Upon his release, he went into exile in the U.K. After studying law, he worked as a policy adviser in the British Home Office.

I tried Chongan’s U.K. number and got no answer, eventually deciding to try him again when I arrived in Dakar, the capital of Senegal, which was about a seven-hour drive away. I used the last of my money on a shared taxi. During the ride, I sank inside myself, trying to disappear.

Visiting embassies

It was almost midnight when I arrived in Dakar. I uncurled myself from the back seat, stretching the kinks and cramps out of my aching muscles. It would be 1 a.m. in England. Under normal circumstances, it would be too late to call anyone. But my circumstances weren’t normal. As I looked at my phone, I hoped a man who knew what it was like to end up somewhere you couldn’t come back from would be willing to help me connect with those who might protect me.

When I reached Chongan, he connected me with one of his trusted contacts: a man named Omar Topp. I met Topp the next evening, barely more than 24 hours after leaving my home. I wanted to stay in Senegal, but Topp warned me that I’d never be safe there: Jammeh had contacts all over the country. He introduced me to a police chief who not only believed my story but convinced the minister of the interior that it was too unsafe to send me back to The Gambia; Jammeh was already looking for me. While the Senegalese wouldn’t let me stay indefinitely, they did put me up in a secure apartment at a secret location and told Topp and the police chief to get to work on finding a country that would accept me as a refugee.

I felt safe enough in Dakar to stop hiding under a niqab or hijab, but still I dressed conservatively: usually in a long skirt and a long-sleeved shirt, with a veil on my head. The human-rights organizations Topp and I visited were supportive but cautious. Some, like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Amnesty International, said they would investigate my claims if I wished them to do so, but it would take time. The embassies were equally cautious: the Americans said that an investigation could take months or longer. The interviewer at the British embassy—a man named Nigel—was friendly and supportive, and I left that meeting feeling hopeful, even as he said he needed to send his report of our conversation to his superiors in order to move the file forward. I didn’t hear from him again.

When the Canadian embassy called me to come in for an interview, it seemed like just another on a growing list of appointments. The interviewer’s office was tucked in the back corner of the UNHCR’s five-storey white office building. At the entrance, topped with barbed wire, a security guard swapped our IDs for visitor passes and waved us inside. The woman who met us was older and unsmiling. She took us to a conference room where she asked me question after question, her face showing no encouragement or sympathy as she made notes of my answers.

As I sat there, all I could think was that my future was in this woman’s control. Or maybe it was all pointless, and I’d have to go through this with someone else a week from now. The emotional ups and downs were flattening me. In that moment, though I knew that her questions were necessary and this was her job, I hated the power she had over me.

Finally, she said we were done. As we left, she told me she’d get back to me, but I was certain I’d never hear from her again, either.

Toronto sounds great

I spent the days that followed waiting—hoping and waiting. During this time, Topp was my closest friend and confidant. In my interactions with Jammeh, I had seen the worst of how a man could use his power: to degrade, to abuse, to harm. With Topp, I saw power used to help. He was under no obligation to listen to me; he didn’t have to spend time with me, didn’t have to care. He could have turned his back on me and said, “Who cares? It’s just some girl. Let her figure it out.” Instead he helped me.

Then one day, Topp arrived at my door. I’d asked him to get me some groceries on the way over. “Guess what?” he said as he entered the apartment.

“What? There are no chickens at the market?” I joked.

His smile was wide. “They’ve transferred your documents to the International Office of Migration. You are going to Canada!”

Relief filled every cell of my body. I was going to be safe. I was going to Canada.

The next day, Topp took me to the International Organization for Migration in Dakar, where an immigration officer named Lamin greeted me. He gave me the details: I had qualified for an IM-1 visa that allowed me to enter Canada and become a permanent resident. But first I had to decide where I wanted to live.

He brought out a map and put it on the table between us. “Where in Canada do you want to go?” he said. He circled Toronto. “Toronto is diverse. There are Caribbean and Black people there and a great transit system and lots of industry, so you can find any kind of work. And it’s close to New York,” he said, pointing to the American city not far away on the map.

I put my finger on the map. “Toronto sounds great.”

In 2015, Toufah Jallow made it safely to Toronto, where she now lives. In 2019, she testified in front of The Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, sharing details of her rape and, in the process, sparking West Africa’s #MeToo movement. In December 2021, the commission decided that Jammeh should face prosecution for murder, torture and sexual violence. Today, Jallow heads The Toufah Foundation in support of survivors of sexual assault.

Excerpted from Toufah: The Woman Who Inspired an African #MeToo Movement by Toufah Jallow with Kim Pittaway. Copyright © 2021 Toufah Fatou Jallow. Published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Next, read up on 10 inspiring women you didn’t learn about in history class.

The world was spinning. Seconds earlier, Beatrice Roberts had been driving her red Ford F-150 down a stretch of stick-straight highway she’d taken for years. Sunlight glimmered in her rear-view mirror as she headed home to Grand Falls-Windsor, a 14,000-person town in central Newfoundland. Inexplicably and in an instant, she’d crossed the yellow line of that familiar two-lane road, and her truck was crashing toward the side of the highway. As the steep ditch zoomed closer, Roberts braced herself. She watched the rocky ridge smash into her windshield, shattering the glass.

A retired store clerk and cook, the 63-year-old had lived in Grand Falls for 20 years. As she was driving, Roberts had thought about her mother, whom she had just visited in Springdale, an hour and 20 minutes away. Last fall, her mother had had a stroke, and she’d lived with Roberts and her husband, Terry, throughout the winter. But by May, the family had decided a long-term-care facility was best, and a weekly ritual had begun. Roberts would spend time with her mother outside, chatting with other residents or watching TV. That Sunday, July 27, 2014, should have been just like the others. Instead, Roberts was screaming for her life by the side of the road.

“The truck is on fire!”

Ryan Folkes could feel the sun on his face as he drove his black Ford F-150 truck along the Trans-Canada Highway. It was a stretch of road he’d been down hundreds of times, just outside his hometown of Grand Falls-Windsor. Here, thick copses of black spruce and balsam fir line the paved two-lane highway, which is so flat you’d think you were in the Prairies. Based in Gagetown, N.B., Folkes was on a week-long vacation from his post as a corporal in the armoured corps of the Canadian Armed Forces. It was good to be home. He hadn’t visited in about a year, and he’d come to appreciate the place more than he had before his nine-month stint in Afghanistan in 2012. Four of his military friends—Ryan Elliott, Nick Bronson, Adrien Guindon (a former soldier) and Lee Westelaken—plus Elliott’s wife, Danielle, had come along for the trip, eager to see the Rock for the first time. It was a vacation six months in the making. They’d spent an idyllic first few days kicking back at Folkes’s family cabin, which the 26-year-old had helped build, half an hour outside of town.

That afternoon, Folkes had planned to take the group to Leech Brook, a trio of waterfalls where locals loved to hang out. The boys had piled into the pickup, Billy Currington’s country song “Pretty Good at Drinkin’ Beer” blaring over the speakers. In his rear-view mirror, Folkes could see Westelaken and the Elliotts following behind in their car. The six would spend the day at Leech and later head into town to Folkes’s parents’ place for dinner—steaks on the barbecue, probably, Folkes thought as he passed a stretch of green.

“The truck is on fire! The truck is on fire!” Rodney Mercer cried out to curious passersby climbing out of their cars to survey the scene. He and his wife, Jennifer, a gynecologist with the Central Newfoundland Regional Health Centre in Grand Falls-Windsor, had skidded to a stop after seeing a red truck roll over a steep embankment on the side of the highway. Normally, their 21-month-old triplets would be in their back seat, but they’d taken Rodney’s parents up on an offer to babysit. Perpetually exhausted, the couple figured they’d make the most of the hazy day and take their new boat out to Badger Lake, about half an hour away.

The Mercers vaulted into the ditch, where the truck had landed on the passenger side. Clouds of smoke emanated from the engine, and Jennifer urged the other drivers to stay back. Rodney, a Grand Falls town councillor and teacher, ran for the extinguisher he knew was buried in the back of the boat behind their car. Sprinting back, he was followed by two men who attempted to dampen the flames that were now shooting skyward with dirt and gravel. A woman in one of the first vehicles behind them to stop yelled out that she was calling 9-1-1.

“Help me!” Roberts screamed over and over from inside the truck. Struggling to breathe, she could smell the smoke. “We’re here,” Jennifer called back. “We’ll try.” Roberts could see the orange glow in the truck’s hood moving closer to where she was pinned, her right foot lodged behind the pedals and her body draped over the inflated airbag. She’d released her seat belt after the crash, a gut reaction that left her deeper in the truck-and harder to reach. The three men were keeping the fire at bay, but just barely. Each time they thought they had put it out, the engine would shoot out more flames. They knew they couldn’t win.

Moments later, the five soldiers ran up. They had pulled over to the roadside when they spotted the smoke trailing into the sky, and they immediately sprang into action. They had each been trained in emergency extraction from vehicles and advanced first aid, and, having served together in the same squadron for nearly six years, quickly fell into a rhythm. Folkes and Westelaken hopped on top of the truck, wrenching the door open with their hands. The smaller of the two, Westelaken climbed inside the cab, taking Roberts’s hand. Folkes hovered above, assessing the damage, before following Westelaken. “Check on the fire,” he told Elliott, who had firefighting experience.

“You gotta hurry up…”

Meanwhile, bolstered by instinct and adrenalin, the growing crowd of over a dozen passersby morphed into a series of moving parts. Danielle directed traffic on the two-lane highway and shooed away rubberneckers snapping photos with their smartphones. Another civilian ripped up a yield sign from the side of the highway and carried it to the truck to use as a makeshift stretcher. The soldiers scrambled to get to Roberts before the fire did, racing against the sparks still flying out from under the buckled hood.

“I need to know how long we’ve got,” Folkes asked Elliott. He looked back at Folkes. Not wanting to alarm Roberts, the 25-year-old responded quietly. “You gotta hurry up,” he said, looking his friend in the eyes. Bystanders handed Elliott fire extinguisher after fire extinguisher, but it wasn’t enough. Until the local fire department arrived on the scene, there was only so much to be done.

Folkes climbed down into the cab’s back seat, and together he and Westelaken managed to shove the front seats back to give Roberts more space. Her left foot was dangling, nearly severed. She had cuts up and down her legs, so deep on the left side the men could see pockets of fat below the skin. “What’s your name?” Folkes asked her, determined to keep her from panicking. He was accustomed to first aid in combat; he’d never seen anything like this so close to home. “Where are you from?” She answered clearly, alert through her tears. The friends worked quickly, and in minutes they’d extracted Roberts and lifted her carefully out through the door, passing her to Guindon and two men waiting at the top of the truck, before climbing out after her. The men laid Roberts gingerly on the yield sign; the soldiers each took a corner, while the civilians followed behind, keeping her legs from swinging. A grim procession, the group carried Roberts carefully to the other side of the road, about 40 metres from the truck.

“Get back!”

At the same moment, Elliott, realizing the blaze had progressed beyond an exhaust fire and was going to blow, yelled at bystanders to get back. Three minutes later, the truck exploded, caving in on itself and sending up a wall of flames that separated Elliott, on the highway’s south side, from the rest of the group to the north. Suddenly alone, the young soldier turned and glanced down the highway. Stopped cars stretched out in both directions beyond the horizon.

With Roberts safely on the highway shoulder, the soldiers and Jennifer, along with two nurses also on the scene, began to treat her injuries as best they could. One bystander hauled over a 12-pack of Pepsi to use as an improvised splint for her injured legs, while another grabbed blankets from surrounding cars to keep her warm. Others pulled first-aid kits from their glove compartments, handing gauze and bandages to the team packing and wrapping her wounds. “How’s it going?” Folkes asked Roberts. “Where were you headed?” Anything to keep her conscious, talking, calm.

Twelve minutes later, the paramedics from Central Newfoundland Regional Health Centre pulled up. “When the ambulance arrived, you could hear a collective sigh of relief,” Rodney says. Jennifer stayed with Roberts as she was lifted onto a stretcher and rushed to the hospital. “She was lucky to be alive,” Rodney says. “Regardless of whether they were trained military or medical personnel, everybody had a role to play in saving this woman’s life. We were very proud to be a part of that group.” Once the emergency-room doctors at Central Health had assumed care of Roberts, the Mercers drove home and rushed inside to hug their kids. It was the last time they’d try to take the boat out for the summer.

Danielle and the five friends never did make it to the waterfalls or the Folkes family dinner that night. Instead, they piled into their vehicles, turned around and headed back to the cabin. “We cracked a couple of beers and cooked up some steaks,” Folkes says. “After that, we just wanted to relax.”

Beatrice Roberts spent three months recovering in hospital in St. John’s, N.L. On October 23, 2014, she was transferred back to Grand Falls-Windsor, where her lung, which was punctured, and her back, which was broken in one place, continue to heal. In the meantime, she’s been receiving visits from her 12 siblings and stitching patches for a patchwork quilt that she’ll work on in earnest when she’s fully recovered. She’s still learning the identities of the people who came together to pull her out of her truck. “Everyone was a stranger to me. I don’t know any of them. It really was a miracle,” she says. “I owe those people my life. I wouldn’t be here otherwise. There were a lot of angels there that day.”

Check out more Drama in Real Life from the pages of Reader’s Digest Canada.

Are you using Apple privacy settings on your iPhone? If not, you may want to reconsider just how much personal information can be exposed. Arbitrary details, such as where you shop, where you work or how you get around town may seem irrelevant but when data is collected and compiled by third-party apps, privacy can easily be breached. Using security features is important to secure your iPhone and prevent a cybercriminal from infiltrating your smartphone.

The iPhone doesn’t have a privacy mode, as Android phones do, but there are Apple privacy settings users can enable to reduce the likelihood their personal information will be compromised. Managing apps permissions is an important step to take back some control of what private information is shared about you and gathered online. (Learn how to spot spam texts on an iPhone or Android.)

iPhone privacy features

iPhones are known to be better than Androids when it comes to privacy and security “primarily because Apple does a better job of forcing users to keep their operating system up to date,” says Jack Vonder Heide, president of Technology Briefing Centers, Inc. and a frequent speaker on privacy and security topics. Privacy features on Apple devices include the following:

Passcodes

Passcodes are a combination of words and letters to access and unlock a device that the user sets. It’s important to create a complex passcode that isn’t easy to crack. It’s also important to use them; iPhones give you the option to turn them off and if you do and your phone winds up in the wrong hands, you’ll have lost this initial layer of defense. (Here’s how to tell if your phone has been hacked.)

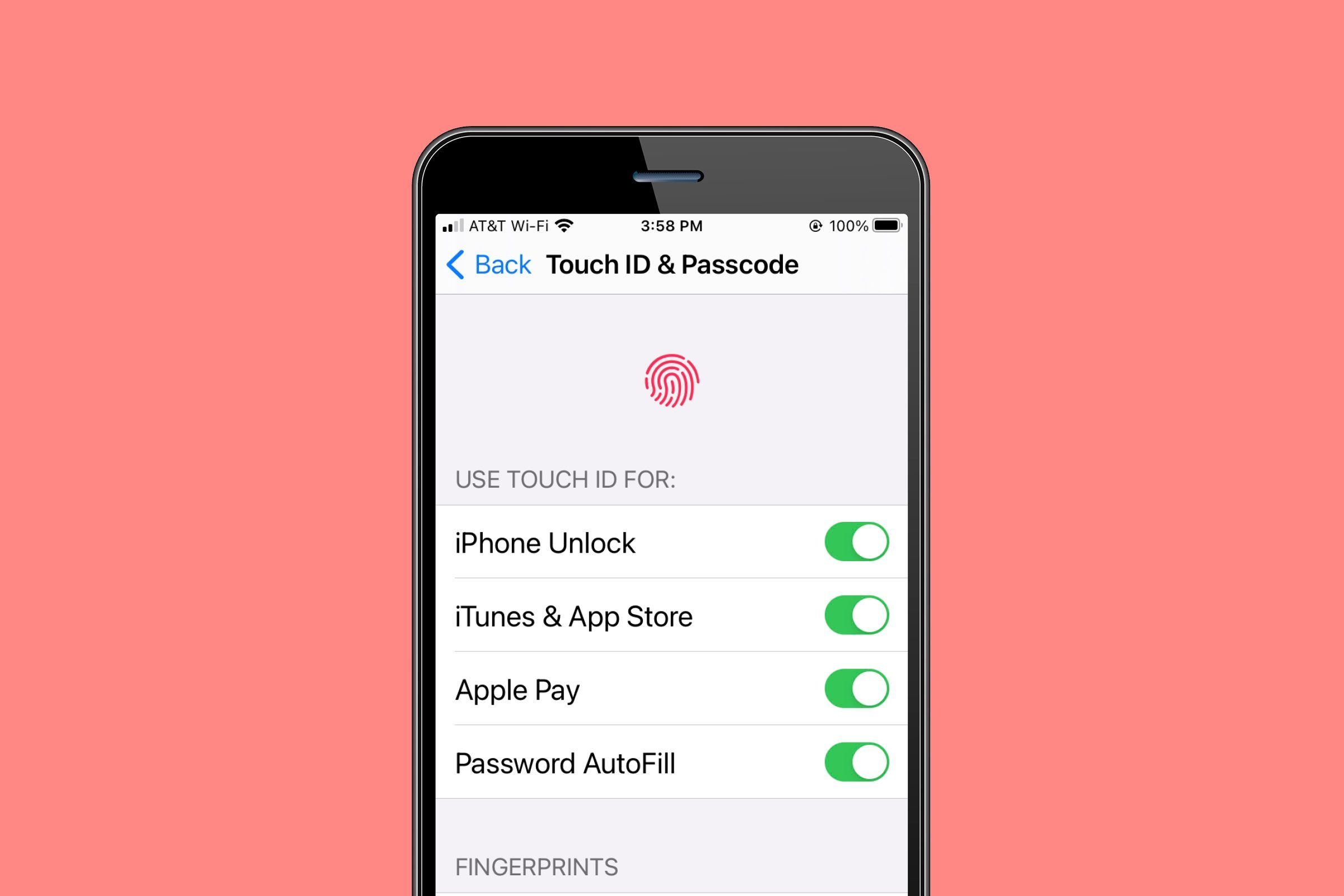

Touch ID

Touch ID is a type of biometric technology, using fingerprints as a layer of security to unlock your device as an alternative to a passcode. The first iPhones to have Touch ID are the iPhone 5s and models up to iPhone 8 Plus and iPhone SE have Touch ID installed.

Face ID

When iPhone X debuted without a home button, Apple introduced Face ID. This facial recognition, a form of biometric technology, allows users to unlock their devices, make payments, and access sensitive information by holding their phones up to their faces. iPhones X through iPhone 12 Pro Max have Face ID. (This is how to spot Apple ID phishing scams.)

Two-factor authentication (2FA)

This is a layered process that requires a one-time code sent to another device, such as your computer or tablet, along with your passcode for more security. “The best protection is 2FA because it is unlikely that a hacker would have the two vital pieces of information needed to log into your accounts,” says Jonathan Simon, professor of digital marketing at the Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa. Additionally, there have been situations where biometrics have been replicated by fingerprint scanners and the like, compromising users’ personal data.

Location settings

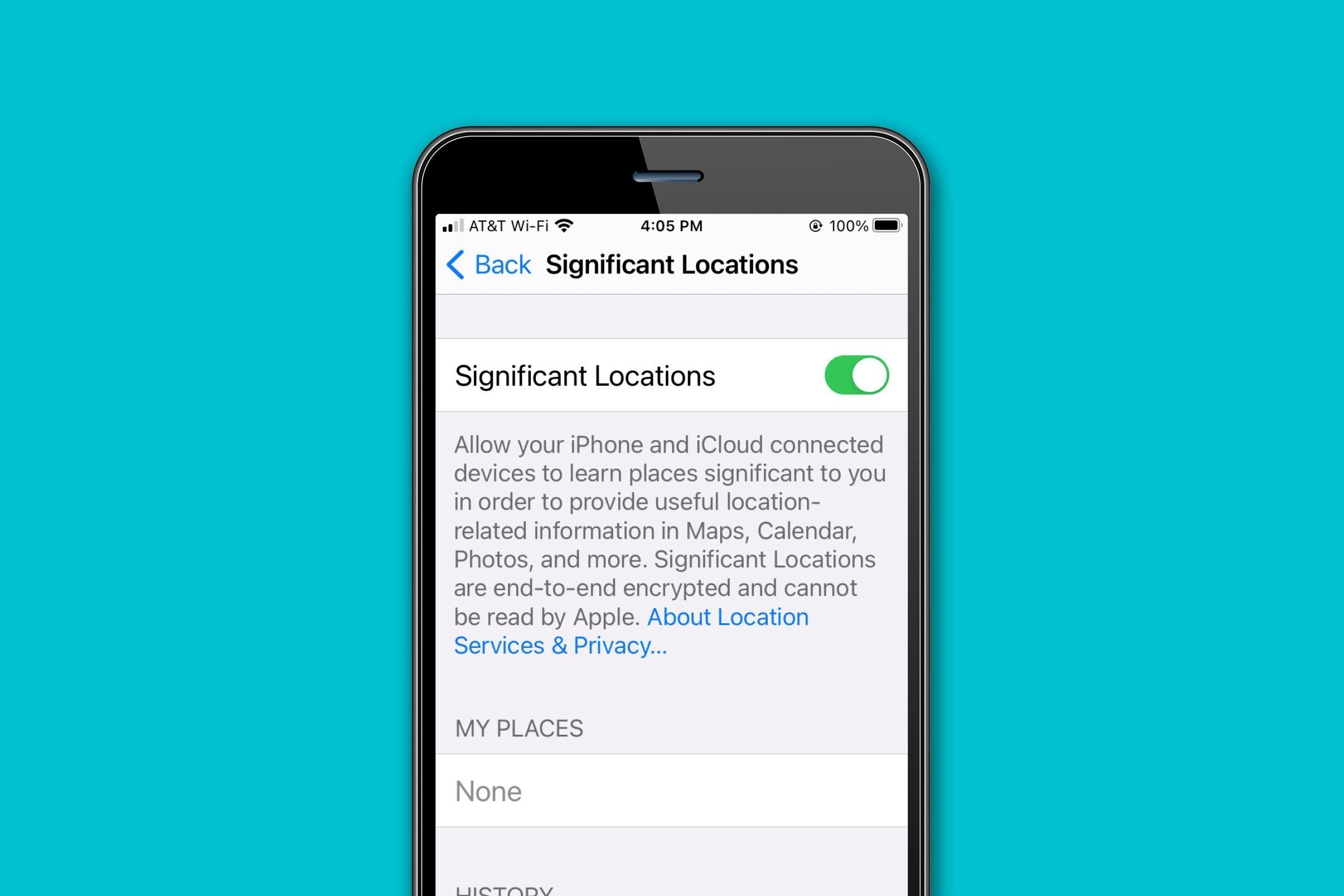

Apple devices are constantly collecting data about you, including tracking your location—when, where, and how frequently you visit a place—to identify your significant locations and offer location-based services ranging from helping you locate the nearest gas station to alerting responders to your location in an emergency. While Apple states they don’t sell your data, the apps you use might to third parties for targeted marketing. “In most cases, you give permission for the app to monitor your location on a continuous basis and to share that data with others.[…] that analyze your activity and push customized advertising to your phone,” Heide says. (You should never post these photos on social media.)

Managing your location settings is fundamental to minimizing the amount of personal information you inadvertently give, especially with apps that don’t need your location to function properly. “People tend to believe they don’t have a thing to hide […but] anyone should be cautious of location tracking and manage it accordingly,” says Daniel Markuson, digital privacy expert at NordVPN. “Technology called fingerprinting cross-matched with the location parameters makes it possible to know who you are and what you were up to without your consent,” he warns.

How to manage app permissions

Managing app permissions is key to minimizing how much personal information is collected from you. “Apps are always tracking your data,” Simon says. “They know when you downloaded the app, when you open it, how much time you are spending in it, and any action you take in the app.” Although there is some information you can eliminate without removing the app, “you should determine what value you are getting from each app and then decide if the information you are required to give is worth it,” Heide suggests. Before installing any app, read the Privacy Policy. “You should never give a ‘go’ to everything an app is asking for, except for the permissions an app cannot function without,” Markuson recommends. Some apps, for example, need to track your location in order to function, such as weather apps, ride-sharing, or food delivery ones, but you can choose to turn off tracking when you’re not actively using the app. Many smartphone apps steal your data so it’s a good idea to monitor your privacy settings. (Here’s how to delete everything on your iPhone.)

How to check app permissions on your iPhone

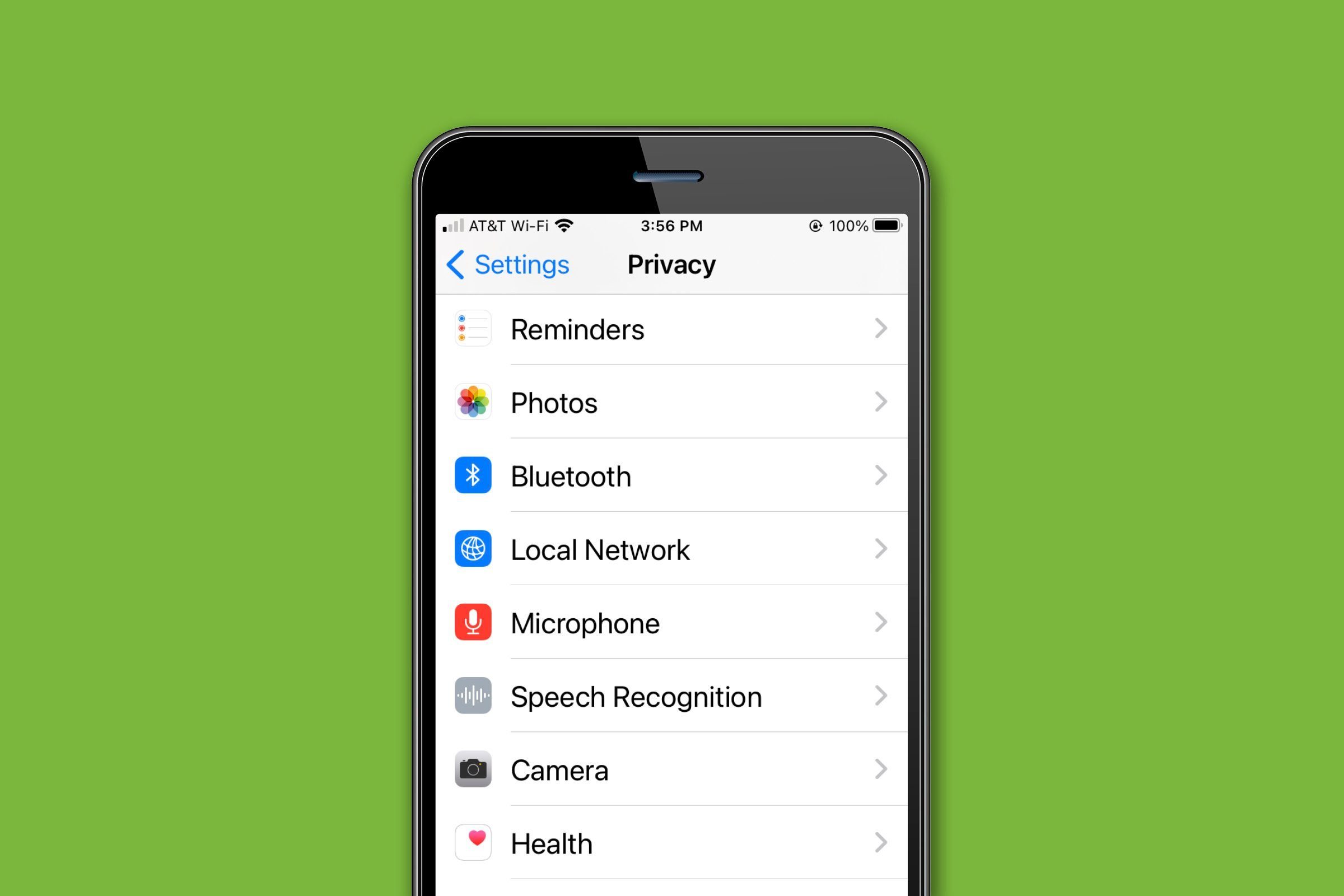

To check your app permissions, go to Settings —> Privacy. A list of different categories, such as Location Tracking, Bluetooth, Contacts, Microphone, Photos, and more will appear. You can click on each specific category to see which apps have access to that data. You can grant or revoke permissions as you see fit.

Next, read about how to clear cookies from your phone.

Midland is a quaint tourist town known as the Heart of Georgian Bay. It boasts (when not in a pandemic) many attractions such as the famous Butter Tart Festival, Martyrs’ Shrine, Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, Wye Marsh Wildlife Centre, Midland Cultural Centre, Little Lake Park and while you’re at it, why not take a tour of the more than 40 murals around town, just to mention a few places of interest.

Take a stroll along King Street downtown Midland and browse through a wide variety of boutiques, bakeries, art stores, to name a few, then continue to the Town Docks. Here you will have the opportunity to relax on the waterfront patio of the Boathouse Eatery with your favourite beverage and enjoy the view of sailboats gliding around Midland Bay.

Being truly a four-season town, not only can you enjoy the incredible golf courses in and around Midland such as Brooklea, Midland and Balm Beach; there are many other activities such as hiking and biking the 95 kilometres of Trans Canada Trail from Midland. Boating is a huge attraction for enthusiasts from all over as evidenced by the variety of boats docked each season here. Georgian Bay has amazing sandy beaches and crystal-clear water that is great for swimming, water-skiing, jet skiing, and the list goes on.

Summer isn’t the only season enjoyed here. Skiing is a big attraction for young and old alike and Mountainview Ski Centre is right here in Midland with 35 kilometres of cross-country ski and snowshoe trails throughout a breathtaking forested area. Thanks to Georgian Bay lake effect snow, Mountainview is the first to get snow and the last to lose it, according to the centre. If it’s downhill you are hooked on, then just a short drive from Midland will take you to Collingwood’s Blue Mountains, Mount St. Louis Moonstone or Snow Valley.

Many famous people were born here or have called Midland home. To name just a few are the Howards (Russ, Glenn & Scott), champion curlers; indie rock band Born Ruffians; Sarah Burke, world champion freestyle skier; former NHL hockey players Roy Conacher, Shayne Corson, Herb Drury, Wayne King, Alex McKendry, Mike Robitaille; and cross-country skier Angela Schmidt-Foster.

After moving back to Midland, I adopted a rescue dog, Charlie. He is a lovable Maltese Shih Tzu and accompanies me on my walks through the trails or just sitting at the waterfront for hours. It’s like a form of therapy just whiling the time away watching others enjoy a stroll at the docks and boats sailing in and out of the harbour. Or we might take a short trip to a local beach on those hot summer days to feel our feet in the soft sand, have a refreshing dip and even stay to watch the most amazing sunsets.

No matter the season or weather, Charlie keeps me out and about town enjoying our numerous walks each day. I’m thankful and blessed to live in such a wonderful town with so much to offer its residents and visitors. But don’t take my word for it, come see for yourself.

Next, check out the 10 places in Canada every Canadian needs to visit.

As winter weather kicks into full gear around the country, it’s important to keep an eye on the news and to be ready to adjust your travel plans as needed. Many drivers who live in cold climates don’t think twice about hitting the road when just a few flakes are falling or there is less than five centimetres of snow on the ground, but according to research, a light snow can be just as dangerous as a snowstorm—even if there is no winter weather advisory.

The Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS) along with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently published a study that found that 54 per cent of snow-related fatal car crashes from 2015 to 2017 occurred when there wasn’t a warning or weather advisory in effect from the National Weather Service (NWS).

“While it might seem like driving in light snow isn’t much to fret about, don’t underestimate the problems it could bring,” says Laura Adams, Senior Education Analyst for DriversEd.com. “Yes, snow is less dangerous than ice for drivers. However, light snow can melt quickly and then refreeze. That turns roadways into sheets of slippery ice, which gives you the least traction possible.”

Even when there isn’t enough snow or ice for a winter weather advisory, you should still stay off the roads if possible, and if you do have to travel, keep speeds low. In 2016, there was a 36-car pileup in Pennsylvania due to a passing snow squall. Even though it wasn’t a blizzard, visibility was really low and a light layer of snow on the ground prevented many cars from braking safely.

“The amount of traction you have between your tires and the road surface determines how your vehicle will respond to sudden stops, quick turns, and acceleration. In many cases, even light snow can cause you to lose traction and skid out of control,” says Adams.

The study also found that only 46 per cent of snow-related fatalities on the roads occurred during a National Weather Service advisory or warning. The NWS also reported that from 2005 to 2016, most snow-related accidents in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—a place very accustomed to snow—occurred when less than five centimetres of snow were on the ground.

Snow is snow, and no matter much is on the road, you should always take it seriously and drive with caution. Before winter weather even starts, Adams recommends making sure your car’s tires have the right amount of pressure and that the treads aren’t worn down so you can have traction on the roads. (This one-second tire test could save your life.) If you are on the road during a storm, stay calm and take things slow to stay in control. Always remember, stopping on snow and ice requires more time and distance. If you do hit a patch of ice or snow, Adams says to never hit the brake, but instead take your foot off of the accelerator and try your best to keep your vehicle going as straight as possible until you feel your tires grip the road again.

Next, find out 9 things you’ll regret leaving in your car this winter.