Angie Deveau had planned to spend Boxing Day of 2013 lounging in front of the Christmas tree with her family. Instead, she had morning sickness and found herself rushing back and forth to the bathroom. That evening, after she read her three-year-old son his favourite bedtime story, cuddled him, and kissed his forehead goodnight, Deveau took a pregnancy test. She’d already guessed what it would say: positive.

At the time she was 34 and lived in a house in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Though she shared custody with her son’s father, she was the boy’s primary caregiver and had only her part-time income as a researcher to sustain them both. She made $25 per hour, working 15 hours per week, and had all the bills that everyone does: housing, groceries, clothing, utilities, and on it went.

Being pregnant made every day a struggle. At seven weeks, she had unbearable nausea. Nibbling on saltines, she tried to work while her son napped. Most days, she had to return to her computer again at night, working into the small hours. Deveau was exhausted and conflicted about having another child. She didn’t have the time or the desire for another kid. She didn’t want a bigger family and knew that she couldn’t afford one.

The path forward was clear to her: she had to schedule an abortion. That’s when she cursed the fact that she lived in New Brunswick. In her province, making the decision to terminate a pregnancy and being able to act on it are two very different things.

Adequate reproductive health care is not uniformly available across Canada. In New Brunswick, where religious stigma against abortion is strong, it’s even harder to access. According to a 2011 Statistics Canada report (the most recent year the agency collected this data), nearly 85 per cent of the province is Christian—compared to about 67 per cent of all Canadians at that time. Here, church parking lots still fill up on Sundays. Traditionally, many in the province feel strongly that pregnancies should be carried through to term.

The province offers four places, in total, to get an abortion: three hospitals, where the cost of the procedure is covered by provincial health care, and one independent clinic, where it is not. Still, while provincial health care may cover the fees of an abortion at each hospital, it doesn’t mean the process is cost-free for everyone—or easily accessible.

Both the Moncton Hospital and the Georges Dumont Hospital are located in Moncton; the Chaleur Regional Hospital is in Bathurst, 220 kilometres north of Moncton. This means 76 per cent of the province’s population is hundreds of kilometres away from any access at all. When these people need abortions, they must take time off work and pay to travel not once, but twice: first for an ultrasound and again for the abortion itself. Add to that the costs of accommodations and potentially also child care, and the procedure is easily out of reach for many New Brunswickers, whose median income in 2015 was $28,107 after tax.

A patient may also opt to go to Fredericton’s Clinic 554. It was originally founded in the mid-1990s as the Morgentaler Clinic. The facility provides sexual and reproductive health services alongside other health care, with 3,000 patients currently on file. Under provincial healthcare laws, the clinic is not reimbursed for ultrasounds or abortions, so it charges between $700 and $800 for the procedure. In fact, New Brunswick is the only province in Canada where abortions aren’t covered outside of hospital settings.

Premier Blaine Higgs has repeatedly defended the province’s current system. “If we felt that we weren’t providing the service in reasonable manner, I mean, it would be a different story,” Higgs told The Globe and Mail in 2019 when asked why he wouldn’t extend abortion funding.

To Deveau, the challenges of getting an abortion at a hospital felt insurmountable. Without her own car, she’d have to take the bus to Moncton, 177 kilometres away, or Bathurst, 254 kilometres away. Plus, at the time, New Brunswick also required that two doctors sign off on the medical necessity of all abortions offered at hospitals. (This requirement was later lifted in 2014 and never applied to Clinic 554.) Getting an appointment with her family doctor usually took weeks. If her doctor signed off, they’d likely refer her to the second required doctor, which would take more time.

Coupled with the wait to schedule the abortion, Deveau was afraid she wouldn’t be able to have the procedure in time to meet the hospitals’ gestational limit of 13 weeks and six days. She decided her best option was Clinic 554 (then still named the Morgentaler Clinic). They were able to see Deveau right away, and her abortion was scheduled for roughly a week later, on a Tuesday. Still, she couldn’t afford the $800 fee—especially not after Christmas—and in the end, her dad loaned her the cash.

Over the years, Clinic 554 has arguably played the role of both saviour and last resort for many. It’s staffed by one full-time employee and about 10 contract staff. That it has also managed to avoid being closed down is no small miracle. Lack of provincial funding most recently drove it to the brink of closure in September 2019, when its medical director, Dr. Adrian Edgar, was forced to put it up for sale. A swell of community support, as well as small donations, helped keep it afloat—but just barely. It had to drastically reduce services over the next year. In October 2020, it was forced to cease providing all non-provincially funded services, including ultrasounds and abortions. By early 2021, Clinic 554 seemed destined to close for good.

In a 2014 Maclean’s interview, Dr. Wendy Norman, a professor of family medicine at the University of British Columbia, said her research shows 31 per cent of women over age 45 report having had an abortion at some point in their lives. It’s likely many women faced barriers in securing that right. While the procedure is common enough, abortion remains taboo and the subject of lobbying and protests by anti-abortion advocates. Politicians of all parties, meanwhile, generally prefer to distance themselves from the issue. Canada has been without an official abortion law since 1988. That year, the old laws, which required a “therapeutic abortion committee” to approve each individual abortion, were struck down by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional.

Dr. Henry Morgentaler fought for abortion rights for nearly two decades before it was legally made more accessible for Canadians. In reality, access is scarce not only in New Brunswick but in parts of every province and territory. Fewer than 17 per cent of Canadian hospitals provide abortions. Those who live in rural and northern areas, or even smaller cities and towns, must travel long distances if they want the procedure. In Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, for example, abortions are offered only in cities, even though 18 per cent of Canada’s population is rural. The Yukon, P.E.I. and Northwest Territories are home to one provider each.

Access varies so widely because health care is a matter of provincial jurisdiction. When Canada’s restrictions were struck down, the provinces were left to dole out access—or prevent it—as they saw fit. In some provinces, doctors are still able to deny care based on moral grounds. Gestational limits also vary by province. In P.E.I., the limit is 12 weeks and six days, but in specific locations in Ontario, Quebec and B.C., abortions are performed well into the second trimester. Of all the regions, Atlantic Canada is the most restrictive.

From 1988 until 2016, for example, Prince Edward Island offered no abortion services, with both the province’s government and hospitals refusing on moral grounds. People had to travel at their own cost to New Brunswick or Nova Scotia—provided they were first able to secure the necessary two-doctor referral. In 2016, advocates eventually threatened to sue the government for a violation of their Charter rights, citing unequal access to health-care services. By the end of January 2017, a reproductive health clinic had opened in Summerside, P.E.I., and the first abortions in 35 years were performed on the Island.

Meanwhile, from 1988 until now, eight different New Brunswick governments, both Liberal and Conservative, have refused to fund clinic-based abortions. Joyce Arthur, executive director of the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada, describes New Brunswick politicians as having their heels “dug in.” Deveau wraps up her feelings on the matter in two sentences: “A few years ago, my husband got a vasectomy, and taxpayers paid for that. The onus is on women, then, to keep our legs closed.”

As a specialist in reproduction, trans health care and addiction medicine, Dr. Adrian Edgar is a firm believer in equal access to health care. His belief was solidified during time spent volunteering in Mae Scot, Thailand. There, Edgar volunteered twice at a refugee health centre, and what he experienced there committed him to this line of work. “We routinely saw people who had tried to self-abort,” Edgar explains. “If you try to obstruct abortion access, a pregnant patient will find a way to control their body, and that might lead to their death.”

Edgar didn’t set out to be a spokesperson for abortion access in the Maritimes. At 38, he is shy and soft-spoken. But he was fired up when he returned to New Brunswick in 2014 and discovered that lack of funding after Morgentaler’s death threatened to close the Morgentaler Clinic in Fredericton. Fearing Maritimers would lose access to much-needed sexual health care and could resort to self-abortion, he helped the community to raise more than $131,000. The facility was renamed Clinic 554 in January 2015, after its street number.

The clinic stands out: one side of the building is painted in the colours of a rainbow. It’s centrally located and by the river. Across the street is the Boyce Farmers Market, where many Frederictonians congregate on Saturday mornings for breakfast.

Since the clinic reduced service offerings last October, Edgar has continued to perform abortions—some are paid by the patient, and some he does for free. But he can’t keep doing it forever. For now, Edgar is taking a wait-and-see approach. In June 2021, a judge gave the green light for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association to sue the New Brunswick government. CCLA argues that the province’s lack of access is against the Constitution. (And, indeed, the Canada Health Act does stipulate that it’s illegal to make Canadians pay for their health care or to pose barriers to that health care. Abortion is included under this umbrella.) Edgar hopes the results will work out in the clinic’s favour and the government will be forced to repeal the delisting of ultrasound and abortion outside of hospital.

“People need access to reproductive health clinics that are local, in their communities, and have on-site staff who understand not just reproductive rights, but also the need for women to be reassured in their decision,” says Melanie Vautour, who works with Fresh Start in Saint John, N.B., an organization that provides housing to women and families. She and three other people volunteer many hours to help women get essential services. This includes driving to and from appointments, securing lodging for women as they undergo or recover from a medical abortion, and providing basic comforts like food and pain medication.

“We are not counsellors or social workers, but we are trying to fill that gap,” Vautour says. She worries about how desperate many women can become when that gap isn’t filled. The WHO estimates that about 68,000 women worldwide die each year from unsafe abortions. That’s about eight per hour. Edgar has repeatedly warned the province that if his clinic closes, some in New Brunswick may try unsafe methods, and people will die. There are no Canadian stats on unsafe abortion, but P.E.I. professor of psychology Colleen MacQuarrie’s research covering her province’s own access deficit suggests several self-induced abortions took place on the Island each year the province refused to provide the service.

At the end of September 2020, just before Clinic 554 reduced its services, Deveau gathered on the front lawn of the New Brunswick legislature with a group of about 30 other reproductive rights activists for a candlelight vigil. Since her abortion in January 2014, she has protested on the lawn many times. Each time there’s an election, or an added barrier to abortion—like, say, a national pandemic—the calls for better access start again, and each time Deveau is there. She doesn’t want other women to go through the same stress and uncertainty and helplessness that she did.

She is now 41, and her son is 10. Deveau doesn’t hide her activism from him; to her, it’s all about equal access to health care. They talk openly about abortion and the importance of choice. He recently chose to write a school report on the 1970s book How to Care for Your Husband and talked about how gender roles have changed since the time it was written. Deveau has now lived through 15 different governments, the Morgentaler decision and countless pushes for better access, and she says that something, eventually, has to give. She keeps going because she knows she’s not alone in her desire for better access to health care.

In some ways, things have started to give. The two-doctor approval is gone. In 2017, New Brunswick also became the first province in Canada to cover the cost of Mifegymiso, a medication containing the ingredients of mifepristone and misoprostol that, together, induce what’s called a medical abortion. The former blocks progesterone, a hormone needed for pregnancy. The latter helps empty the contents of the uterus. It isn’t a perfect solution. In Canada, Mifegymiso can be prescribed only up to nine weeks gestation.And while New Brunswick foots the bill, in some provinces it can cost up to $450.

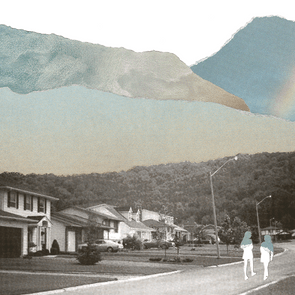

In the meantime, the lobbying continues. Around the same time as the candlelight vigil, protesters from across the province met to demand better access. They took over the sleepy town common in Rothesay, N.B., then-health minister Ted Flemming’s district, on a sunny Thursday afternoon. About 50 people, most of them young, sporting buttons and carrying signs, camped out for hours, even as Flemming refused to speak with them. He’d barely addressed the issue at all during his term. The protest ended at Flemming’s suburban house. It was just hot enough to break a sweat on the way up the hill from the common. Each protester carried a sign. My body, my choice. One by one, they stepped up to Flemming’s door and laid their signs to rest, for him to find.

Next, read about this Ontario doctor who helps breast cancer patients prepare for treatment.

In March 2020, when we were hit with COVID-19, most of us were surprised and in a bit of a daze, not fully understanding just what that meant—or would mean—for ourselves, others, our community, and different parts of the world. Early coverage of COVID-19 compared what was developing to the “Spanish Flu,” an influenza pandemic just over 100 years earlier, lasting from 1918-1920.

Thinking about this, I realized my parents would have been in their teens in 1918—and that they had lived through that pandemic. And yet, I grew up never having heard them speak of it or their experiences! I had questions about what it was like for them, but no answers since my parents are no longer with us.

I thought to myself, “I don’t want this kind of thing to happen to the younger generation in my family in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

I spent the first eight months of the pandemic taking in all the new and changing information, adjusting to the uncertainty and restrictions, wondering about my parents’ experiences and thinking about how I might be able to help pass on information to younger/future generations. One day in December 2020, I woke up knowing what I wanted to do. I had a vision of a family quilt documenting our family’s experience of the pandemic. The idea excited me because I’ve always loved quilting, sewing, knitting, and other fibre crafting. Also, I was facing another winter, this time with a lock-down and stay-at-home order; I really wanted something creative to do so I wouldn’t feel as isolated.

of Lois’s family contribuuted to the pandemic quilt she conceived of to keep the memories alive.

I ran the idea by my family members—my four adult children (with invitations also to their spouses and my eight grandchildren). They all gave it some thought and said “Go for it, Mom!”

So, I asked each person to create a square to convey their views on and experiences of the pandemic. We did some brainstorming together, including ways to include some family members providing essential services without taxing them too much. I ordered the fabric and quilting supplies we needed. One of my daughters sourced some good acrylic fabric markers. And we found a good local shop that did a great job printing photos and other designs onto fabric.

Each family unit contributed a few completed squares for a total of 20 squares. Some of us made more than one square, collaborated with and/or helping one another. The quilt covers three generations: the youngest family member is 17 this year, and I’m the oldest at almost 83. The quilt took my family and I almost four months from the time I envisioned it to the day I finished sewing it up.

Once the pandemic has ended, I will stitch the end date and any other key information onto the inside of the quilt. It may not be as skilled as some of my earlier work—I hadn’t made a quilt in a long time!—but it’s certainly one of the most creative and exciting things I’ve done, already serving the cause of bringing our family closer together. Seeing it completed—my vision realized, and knowing that upcoming generations will learn about our family experiences firsthand and not be left in the dark as I was as a child—is a dream come true.

Next, get inspired by the stories of 30 Canadians who reveal what they’re most thankful for.

Reader’s Digest Canada: Your new novel, The Apollo Murders, takes place on a mission to the moon. I guess you subscribe to the adage “write what you know”?

Chris Hadfield: It’s more about being compelled to share these miraculous and rare experiences. I was the first Canadian to walk in space, the only Canadian to command a spaceship, and I served as commander of the International Space Station. I could just keep it all to myself, but that feels like a waste. Since retiring from the Canadian Space Agency in 2013, I have come up with new ways to share my expertise and passion for space exploration. The novel is another platform and also a challenge that I was eager to attempt.

You set your book in the Cold War era. Why?

That was a very exciting and fruitful period in terms of the history of space exploration. When I was born, going to space was impossible. In 1961, the first person flew in space. The space shuttle Columbia flew in 1981, and nearly 20 years after that we started living on the ISS. Now another 20 years have passed and we’re on the brink of not just getting to the moon, like they do in The Apollo Murders, but of actually settling there.

What does that look like, exactly? Are we talking about suburban life, but on the moon?

For so long, both cost and risk made getting to the moon something that was only attempted by a very small group. But we now have more affordable and reliable ways of getting to the moon. We also know that the moon has water frozen into craters and a power source in the sun. We have to figure out how to extract that and start to grow crops as part of building a safe, permanent habitat. A lot of the work can be done by probes and robots. The joke is that, if we do this right, the robots we send ahead of us will hand us a martini when we get there.

What about the criticism that we should instead focus our investment on solving problems here on Earth?

It’s about balancing investment. Certainly there is a lot to be done to solve issues happening on our own planet, but exploring the universe is part of that. We have to look at the history of extinction events and how another habitable planet could mean the survival of humankind. Carl Sagan has said that the reason the dinosaurs died is because they didn’t have a space program.

There has been a lot of debate recently about whether we should be settling the moon or Mars. What’s your take?

When we’re talking about travelling to the moon versus travelling to Mars, it’s the difference between building a vehicle to get to your cottage and building one to get to Australia. Mars is not only far beyond the Moon, it’s often on the other side of the sun, and there is a lot of risk associated with making that trip. There is also a lot to be excited about. We know that the moon is a lifeless planet. There is no evidence of life on Mars—yet.

Life as in Martians?

At this point, the speculation is around microbial fossils, but we will know more when specimens from the Perseverance rover return to Earth, potentially by 2031. On Earth, we have a fossil record of almost four billion years of life, starting with single-celled organisms. And, we know that Mars and Earth were very similar at the time that life developed on Earth. So when you look out into the universe and the infinite number of chances for life to develop, it seems pretty arrogant to think that we’re it.

Next, find out how Canada made the moon landing possible.

From the time he was four years old, Woodie Stevens has spent every summer of his life at his family cottage in the Thousand Islands, a 10-minute boat ride from Gananoque, Ont. But it wasn’t until his 20th summer at the cottage, when he thought he had that part of the province all figured out, that the islands and the river reached out and spoke to him—and changed the course of his life.

Woodie, born Ford Woods Stevens, is now 79 years old. He’s a career dentist in the Philadelphia area, a gentle soul who can spin a good yarn. His cottage, which has been in the family for more than a century, sits atop the highest point on Wyoming Island, some 18 metres above the St. Lawrence River. It features an impressively level stone patio just outside the door, a perfect plateau of Canadian Shield granite, courtesy of Mother Nature. The patio faces downriver to the east but also offers a clear view south toward Grindstone Island, just across the invisible line in the water that marks the Canada-U.S. border.

The Thousand Islands were Woodie’s summer playground as a kid, the place where he learned how to swim and paddle and fish, and how to get into and out of trouble. At age 15, he and his pal Gordie once found a giant anchor stone at the bottom of the river and decided to haul it out of the water and up to the patio. It took them five days.

By the time he’d reached his 20s, Woodie was living a carefree and careless life. “I was full of beans as a young man,” he says. “Always running around, always talking.”

Then, one beautiful morning in the mid-’60s, he woke up early and saw his father, Ford Stevens Sr., out on the patio.

His dad (also a dentist, and one of the founders of the Academy of General Dentistry) was sitting in one of the family’s homemade chairs, which they call “island rock chairs.” They look like a pre-historic prototype of a Muskoka chair, the kind of thing an archaeologist might unearth. They have the same sloped seat, wide armrests and tall backrest. But they are less rounded than Muskoka chairs, more angular and boxlike. The backrest is made of only two wide slats of wood. The armrests are untapered. The chair’s rudimentary appearance is key to its charm.

“He was having a coffee and watching the sunrise, so I got up, got some coffee and went out. Of course, I was full of bubbles and that stuff, and he just went, ‘Shh,’” Woodie recalls. “He said, ‘Quiet. Sit down. Sit down and listen.’”

Woodie sat in the island rock chair his dad had made for him when he was just a kid. Woodie obviously wasn’t inclined toward quiet serenity at this point in his life, but the chairs, with their reclined seats and backrests, have a way of encouraging people to settle. He gently lowered himself into the seat and the chair took hold of him, and he tried listening for a change.

The problem was that Woodie truly had no idea what he was supposed to listen for. Voices? Motorboats? A malfunctioning septic system? “I said, ‘Listen to what?’ And Dad said, ‘Sit and listen.’ I thought I was in trouble again so I kept quiet.” Moments passed. Then his dad said, “Listen to the river. ”

Woodie listened. He was sitting on an island with the mighty St. Lawrence rushing past him on all sides, but to him the river had become inaudible. It took him a while to locate the sound of its churn beneath the loon calls. You have to listen past the wind to hear the water. Finally, he heard it and isolated the sound in his mind. Then he looked at the river anew. “My dad said, ‘This river has passed by this island for millions of years at six miles an hour. You’ve got to design your life like that.’”

It was an epiphany to him: those words, spoken in this place at that moment, suddenly gave him a new perspective on his life, his family, adulthood, the world. The lesson he took from the moment wasn’t that he needed to slow down to six miles an hour, and it wasn’t just that he needed to find a more sustainable pace for his life. He also understood that he needed to learn to halt life’s perpetual rush, fast or slow, and be still—and that his grandfather, as it happened, had designed the perfect chair for this very purpose. Even when you’ve got an island cottage like Woodie’s—as literal a metaphor as you’ll ever find for stepping outside the fray—it’s not an easy thing to do.

The Stevens clan has, through generations, been characterized by its combination of hospitality and contemplation, which helps explain how the family ended up with this cottage in the first place. Wyoming Island got its name from its initial purchasers, two Methodist ministers from Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley. They quickly decided the island was big enough for four families and, recognizing they had a rare opportunity to choose their neighbours, in 1910 invited two of their friends, young family men both, to come visit, and to buy in.

One of those friends was Woodie’s grandfather, Junius Stevens. He purchased the island’s southeast corner, which happened to be its least accessible area from the water, yet its most majestic once scaled (funny how those things go together, adversity always leading to reward). Junius then contracted a Grindstone Island farmer, Hiram Russell, to build a one-room camp and to complete it in time for the following summer.

Back then, it was arguably easier for Hiram Russell to build that camp than it was for Junius Stevens to go and enjoy it. The Stevens family’s voyage to their summer retreat was an annual crucible, and it is a testament to their destination’s beauty that they endured it. At 420-odd kilometres, the trip from Kingston, Penn., to Gananoque, Ont., which is roughly the same distance as Ottawa to Toronto or Edmonton to Banff, lasted three whole days. Junius owned a motor car and drove it—with his wife, Fannie, and their two children—on unpaved and badly potholed roads, stopping repeatedly to fix flat tires and to push through muddy ruts.

There were no hotels or motels along the way; just roadside tent camping and campfire cooking. The trip was capped by a ferry ride from Clayton, N.Y., to Gananoque, and then 90 minutes of toil in a rowboat to Wyoming Island.

Nor was life any easier once they arrived. There were regular rowboat outings to Grindstone for milk and other necessities, and all the cooking took place outside on that stone patio. All this in order to spend the summer in a one-room cabin with an outhouse.

Junius designed and built his original island rock chairs out in the open here, as well. The original chairs he built for himself and Fannie are still there on Wyoming Island, beneath their favourite pine tree.

Skip forward a century or so, and that one-room camp is now a three-bedroom cottage with a full kitchen, plus a second building that features its own miniature suite and, around back, a giant workshop with every tool you could possibly need. The second suite is for Woodie’s brother, Jim, and his wife, Darlene; as the family has grown, so has the

family compound. As their kids have become adults, they all

share in the cottage’s operating expenses, with everyone paying annual dues for taxes, repairs and maintenance. It’s an unsentimental way to organize the business end of the family cottage, but it works. Once everyone pays up, they are free to indulge in relaxation and nostalgia.

These days, Junius’s 72-hour excursion has become, for Woodie, a six- hour drive from Philadelphia to the Gananoque marina and a 10-minute ride in Chips, the family’s vintage mahogany motorboat.

“If you think you really like a girl,” Ford Stevens Sr. told his restless son back in the ’60s, “bring her here.” This was the sagest piece of advice Woodie’s dad gave his sons about choosing a partner. Island cottaging isn’t for everyone: even when you’re not alone you remain symbolically surrounded by a void, outside life’s currents, cut off from the rest of the world. Some people—the Stevenses, for example—find that liberating. Others find it suffocating. If your steady likes it here, explained Ford, the relationship has potential. If not, it’s doomed.

This is precisely what Woodie did when he met young Lini Westland on a nearby Howe Island dock in 1971. Woodie, 29 at the time, was out on the water with two friends, zipping around in one of his buddies’ motorboats, when they spotted three girls sunbathing at Bishops Point one summer afternoon. Lini, then 21, was sharing a cottage rental with two friends. The boys offered them a boat ride, and Lini’s friends said yes. Lini thought the whole thing was sketchy, but she wasn’t about to leave her friends or be left alone on Bishops Point.

Woodie and Lini hit it off immediately. Woodie told her he was planning to go back to school and become a dentist. “When he told me that, I realized he had a dream and some ambition,” she says.

Woodie was deeply enamoured, too. Their conversation turned easy and intimate while Woodie’s buddies were still trying hard to impress the other girls. Later that afternoon, the group split up, and Woodie, though he’d known Lini for no more than a couple of hours at this point, didn’t see any point in wasting time. He brought Lini to Wyoming Island for the litmus test.

She liked it from the outset. “I thought this whole place was really beautiful. And his father liked me right away because I paid attention to the stuff on the walls.” She also got her first taste of the Stevens’ unique, homemade family cottage chairs on the stone deck and made a point of saying how comfortable they were. “I asked about everything and told him how wonderful it all was, and I meant it.”

Lini and Woodie spent a week at the cottage alone later that summer. Within five months, Woodie had achieved the following milestones: he proposed, he and Lini were engaged and then married, and Woodie built Lini her own rock chair.

When Lini gushed to her future father-in-law about the family cottage, it was no small compliment. The walls of the Stevens family cottage are replete with built-in shelves, hooks, mantels and plate rails, the better to festoon them with tchotchkes and quirky artifacts. It’s a living family archive that puts their values on display.

And it’s a display so rich that it’s actually hard to see the walls themselves. Toby jugs. Commemorative plates. Family photographs. Model boats. Muskie mounts. Busts of ship captains. Two American flags in triangle fold—tributes to relations killed in war. A ship’s wheel. Regatta silverware galore, from medals to banners to plaques. Beer steins. Family sayings and poems.

What Lini noticed in particular—what everyone notices—was the bedroom door off the dining area that doubles as a logbook. It’s a beautiful old door, solid wood with four recessed interior panels. Every inch of that door—the panels, the borders, top to bottom—has a log entry inscribed into it. One side of the door, unpainted, covers the period ranging from the interwar years to the 1960s. The other side of the door, painted blue and white some 50 years ago and never to be repainted, contains entries running from 1971 to the 1990s, when they ran out of room.

The door looks better than it reads—if you parse the Stevens’ door log, you’ll learn that they got a new dishwasher and electric range in 1972; you’ll read about water levels and first swims and first paddles; you’ll find the names of dinner guests; and you’ll see the outlines of their kids’ feet, showing how they’ve grown over the years. But cottage logbooks aren’t meant to be great literature. They are meant to mark the passage of time in a place where time stands still. No one bothers keeping a logbook of their city home; we buy and sell urban dwellings like the commodities they are, and whatever traces of ourselves we leave behind will be forgotten with the next reno. But our cottages are truly ours, and we make our mark indelible upon them.

When Woodie’s dad first told him to be quiet and listen to the river, it felt to Woodie as though his dad was passing on a piece of wisdom he’d always known, a lesson he always knew his son had to learn and that he had just been waiting to impart to him when the time was right. But of course, that’s not true: his father was also a restless young man once, and he also had needed to learn to be still, as did his father, Junius. This is surely why Junius invented his own cottage chair.

Despite its rough appearance, the Stevens cottage chair is the most comfortable version of the Muskoka-Adirondack chair I’ve ever sat on. The angle of the seat is not as steep as in a true Muskoka chair, making it easier to get in and out. And your spine fits neatly into the space between the two backrest boards, allowing your shoulder blades to press flat against the backrest.

In the Stevens chair, you also sit a little taller, making it easier to converse with others, read or write in a notebook on the armrest. Or to simply look out over the horizon and listen for the river, and to feel its power, even when you’re not immersed in it. Island cottaging teaches you to step outside the current, watch its flow and not react, nor respond, nor go with the flow or against it. The only way to be still is to sit still.

Next, check out the story behind the fascinating origins of butter tarts.

© 2021, Philip Preville. From “A Family’s Homemade Chair Is More Than Just a Place to Site,” Cottage Life (August/September 2019), cottagelife.com

Back in 2017, Hani Al-Dajane was struggling to figure out where he fit in. Al-Dajane, then 25, was the only Arab at the Toronto law firm where he worked. Every time he scrolled online, he saw mainstream media stories filled with negative stereotypes about his culture—if they included Arab perspectives at all. And, within his own Arab community, he felt there weren’t enough spaces for young people to talk about the issues that mattered to them, such as racism, gender equality or LGBTQ rights.

Finally, he confided in his friend Mays Alwash, a 24-year-old biology student. Both Al-Dajane and Alwash had moved to Canada from other countries (he from Kuwait and she from Iraq), and hit it off in university. Alwash was similarly troubled by the dearth of Arab voices in Canadian society. She also had difficulty connecting with other Arabs about seemingly taboo topics, which made her feel even more unrepresented and isolated. “We realized we couldn’t be the only ones feeling this way,” says Al-Dajane.

The solution, they decided, was to host events for like-minded young Arab adults. In May 2018, they launched Yalla Let’s Talk! (yalla is Arabic for “Come on!”) as an event series, spreading the word through Arab-Canadian youth leaders and social media influencers. Six months later, about 50 participants in their 20s met at a café in Mississauga for the first event. People sat in a circle with Al-Dajane and Alwash moderating. They opened with questions about “choice.” What choices are yours, and what choices are controlled by family pressures? One person likened the idea of community to a chain: there’s only so far you can move before the chain pulls you back. That resonated with others. Like Al-Dajane, the group wanted to loosen their chains without discarding their rich Arab heritage.

Soon, Al-Dajane and Alwash began holding monthly meetups across the GTA. Anyone who identified as Arab or with the immigrant experience could participate. YLT then expanded its volunteer-run events to London, Ont. and Montreal, as well as to cities in the United States and the United Kingdom. In its first year, YLT held 20 café meetups that hosted nearly 1,000 people.

“The meetups were all about encouraging conversations that are usually swept under the rug,” says Alwash. Muslim women who wear a hijab shared the challenges of using dating apps. Black Arabs spoke about the racism they encountered. Some participants shared stories about their experiences with trauma. Others came out as LGBTQ for the first time among other Arabs.

In 2020, with in-person events postponed because of the pandemic, the organization began hosting free YLT virtual cafés via Zoom every Saturday. More than 1,500 people from around the world have attended. Then, last fall, Al-Dajane and Alwash found a way to expand the conversation even further, turning YLT into a full-fledged media company that produces content both as an online magazine and through an Instagram account. Arab staff writers and guest columnists write about subjects as varied as divorce, masturbation, women’s rights and mental health.

Today, Al-Dajane is a lawyer at Emerge LLP, a firm that helps entrepreneurs, which he also co-founded, and Alwash is a PhD candidate in molecular biology at the University of Toronto. Neither feels isolated or anchorless anymore—they’ve built a new community and a meaningful Arab identity for themselves. “We all have different goals and values,” says Al-Dajane, “but the new generation of Arabs has one thing in common: a desire to make a positive difference.”

Next, check out how a mentorship program in Toronto helps vulnerable youth succeed.

Beneath the ocean’s surface waits a different world—quiet, full of wonder, shimmering with life. Carter Viss loved that world. It’s why he left Colorado to study marine biology at Palm Beach Atlantic University. It’s why he got a job at the Loggerhead Marinelife Center, just up Highway 1 on Florida’s east coast. And it’s why he spent so much free time snorkelling in the reef system just a couple hundred metres from the famous Breakers resort in Palm Beach.

This particular Thursday morning— November 28, 2019—was especially nice. It was Thanksgiving. Tourists and locals alike hit the beaches. The water was flat, the sky blue and the underwater visibility spectacular. Twenty-five-year-old Viss and his 32-year-old co-worker, Andy Earl, spent a couple of hours among the sharks, eels, turtles, octopus, lionfish and angelfish. They netted some small specimens for Viss’s personal collection. Finally, around noon, they headed for shore.

To a diver underwater, outboard engines have a clear, unmistakable sound. On the surface, however, swimming the crawl, Viss didn’t hear the powerboat until it was almost on top of him. When he saw it, he knew he had just an instant. He pulled desperately to one side, getting his head and upper torso out of the boat’s path before it ran him over.

He braced and tumbled. The seawater around him turned crimson. A severed limb was sinking to the bottom—a human arm, the hand enclosed in a black diver’s glove.

This couldn’t be happening, he thought. It was too bizarre.

Inhaling blood and seawater, Viss realized he would drown if he didn’t swim. But he couldn’t swim. His right arm was gone. Both his legs were smashed, dangling uselessly beneath him, and his remaining hand was damaged. Screaming for his life, he slipped beneath the surface.

Andy Earl heard his friend’s mortal terror. So did Christine Raininger, an expat Canadian who was sitting on a paddleboard nearby and had yelled at the boat to slow down. They reached Viss at about the same time. While Andy kept Viss’s face out of the water, Christine squeezed his upper arm to stem the blood flow, then fashioned a tourniquet from the cord on her paddleboard.

Meanwhile, the 11-metre speed-boat, named Talley Girl, was reversing urgently. It was powered by three massive 400-horsepower Mercury outboard engines with five-blade propellers. On board were retired Goldman Sachs executive Daniel Stanton Sr., his 30-year-old son, Daniel Jr., his son-in-law and two grandchildren. Daniel Jr. was at the wheel. Horrified, in shock, he helped Earl and Raininger load Viss onto the dive platform at the boat’s stern.

I’m not going to make it, Viss thought, pain searing through the adrenalin. No way I’m gonna make it.

Earl, too, feared his friend’s wounds were not survivable. “God is with us,” he reassured Viss, over and over, holding his hand as Talley Girl made for shore. “God is with us.”

Viss, a devout Christian, felt his fear and panic melt away. In its place came total surrender, a kind of blissful acceptance. Dying felt like diving down into another beautifully peaceful realm.

As it turned out, the worst day of Viss’s life was not without things to be thankful for. Earl and Raininger being so close, for one. The speedboat reversing so quickly. The first responders who waded into the ocean to meet Talley Girl. The ambulance that raced to St. Mary’s Medical Center. The 12-person critical-care team, already briefed and suited up, that received Viss in the trauma bay barely 20 minutes after the boat strike.

Also fortunate was the fact that Dr. Robert Borrego, a critical-care surgeon and the medical director of trauma at St. Mary’s, was in the middle of his shift. The son of a Cuban fisherman, Borrego had come to America at age nine. Thirty years at St. Mary’s and a stint at a field hospital in Iraq had acclimatized him to dealing with massive trauma.

Many soldiers he’d worked on had been devastated by improvised explosive devices. Borrego did a quick assessment. Major open wounds in the ocean are doubly perilous because the victim’s bleeding is not slowed by clotting and infection is very likely. Viss was clearly in Stage 4 shock, meaning he’d lost at least 40 per cent of his blood volume and was on the verge of multi-organ failure. His right arm had been retrieved by a diver, but there was no hope of reattaching it.

Borrego noted the damaged left hand and wrist. The right knee was dislocated and deeply lacerated, the kneecap was nearly severed and the femur had a fracture. The lower left leg and ankle were smashed, with deep gashes in the flesh. The left foot was turning blue.

It was a miracle Viss had gotten to the hospital alive, but every moment counted. One option was to amputate both legs. Amputation could be done quickly and would lower the risk of infection. Because Viss was young and otherwise healthy, Borrego and his team decided it was worth trying to save them.

Three surgeons and two residents set to work together. First came a guillotine amputation of the mangled stump of his arm. That wound would need to be regularly trimmed and washed with antibiotics to ensure it was infection-free before being closed. Next, each leg was reset and encased in a fixator, a sort of exoskeleton that maintains proper alignment as the bones begin their slow process of repair. Fractures in the left hand and wrist were also set and soft-tissue damage repaired. Three and a half hours later, liberally infused with saline and eight units each of red blood cells, plasma and platelets, Viss was moved to the ICU.

The next 48 to 72 hours would be critical. The human body can only fight so many battles at once before shutting down. All anyone could do now was wait, and hope, and see if he’d pull through.

In Centennial, a town outside Denver, Chuck and Leila Viss were taking a chilly, snowy walk after Thanksgiving Day church service when Leila’s cell- phone rang. The call display showed a Florida number. She assumed it was a telemarketing robocall.

Back in the car, heading home to start dinner, she saw there were two voicemail messages. She put the phone on speaker so Chuck could listen, as well. It was a sheriff in Palm Beach County. As the mother of three active boys—Carter was her middle son— Leila wondered: what’s Carter done?

“Boating accident… lost one arm… trying to save his legs.”

Panicked, weeping, they pulled into a parking lot. “We took turns losing

it and comforting each other,” said Leila. The day became a desperate, blurry scramble—cancelling dinner, urgent calls, sobbing helplessly, work plans, trying to book flights on a holiday. Chuck’s persistence paid off when he found two seats out of Denver that evening, with a layover in Boston.

If there’s such a place as purgatory, it just might resemble Logan Airport at 4 a.m. when you’re so emotionally spent that you’ve run out of tears, unsure whether your son would be alive when you reached him. And daring to contemplate whether, if he ended up with just one limb, it might be better if he passed—this young man who lived to snorkel and fish and play guitar and piano.

If Logan Airport is purgatory, a hospital’s ICU could be the high-stakes room in a casino. You can’t tell whether it’s day or night. People move with purposeful efficiency. The atmosphere is generally calm but intense. The difference, of course, is that what’s at stake in a hospital is not just money but life itself.

Frayed and exhausted, Leila and Chuck Viss reached St. Mary’s around 10 a.m. The sight of their son in the ICU, swollen and bandaged, right arm missing, fixators on his legs and tubes down his throat, was overwhelming. Leila and Chuck had to be helped out to compose themselves.

So began their vigil. The Visses took turns by his bedside, where Carter was hooked up to a ventilator. He was tormented by hallucinations—“ICU psychosis,”doctors call it. He knew his family was there, tearful and comforting, but so were strange, gruesome creatures that were crawling all over him.

“Get them off me,” he begged.

Viss didn’t know he’d already had four operations. Infected flesh had been excised, a titanium rod inserted in his shattered tibia and hardware installed in his left wrist and right knee. Nor did he recall the many emotional visits he’d had from church friends and Loggerhead colleagues.

Chuck, as an employee of Oracle, the software company, was able to work remotely. Leila, a church organist and piano teacher, needed to be back in Centennial. So Chuck took up residence in a nearby condo and Leila commuted.

One morning, after Viss had been extubated, Borrego told him the battle was 90 per cent won. I’ve got a long road ahead of me, Viss realized, but I’m gonna make it.

He decided he would use his spared life to educate others about ocean safety and conservation. Heading into yet another surgery, he told his parents, “I can make a bigger difference now than I ever could before.”

Over the 68 days Viss spent in hospital, his recovery felt agonizingly slow. Actually, says Borrego, it was remarkably fast. His parents noted each milestone. The first day he sat up. Being moved out of ICU to a “step-down” room. The first time, after surgery on the nerves in his right knee, that he wiggled his toes. The first time he sat in a wheelchair. The first day he ate the hospital Jell-o and chicken broth Chuck had brought him. The morning he wore his own clothes. And then, a week later, Viss standing unaided, and a few days after that his first shaky, excruciatingly painful steps.

But another battle had just begun. Heavy doses of morphine, oxycodone and fentanyl had eased his pain. Now, as Borrego explained to the Visses, a successful outcome depended on Carter getting off opioids: “I’ve seen many lives ruined when patients can’t break free.”

The Visses have friends who’ve lost family members to overdoses. Carter, too, understood the gravity of the issue. He gradually reduced his dosages until, determined to use nothing more than Advil and medical marijuana, he tore off his fentanyl patch. Withdrawal made for a harrowing few days, but then Viss, as Borrego puts it, “has incredible mental strength, just extraordinary.”

Viss was discharged from St. Mary’s in February 2020. By June, just seven months after the accident, he returned to work. His duties aptly include helping with the rehabilitation of loggerhead sea turtles that have been injured in boat strikes.

Today he can bend his right knee only 90 degrees. For a while, residual infections had him on and off antibiotics. He’s been fitted with a prosthetic arm but finds it cumbersome. All in all, says Borrego, his recovery has been almost miraculous.

Physical healing is one thing. The emotional legacy is less obvious, more nuanced. “The accident itself,” Viss says, “I try not to remember how real it was, the panic and horror. It feels more like remembering a dream now, or a nightmare. And I try not to think of what I can’t do and focus on ways to work around things.”

An investigation by Florida Fish and Wildlife found that Talley Girl had been going at least 80 kilometres per hour when it struck Carter. The agency faulted Stanton Jr. for operating a vessel within 90 metres of diver-down warnings; reckless operation of a vessel; failing to maintain a safe speed; and failing to maintain a proper lookout.

Last September, Stanton was charged with wilful and reckless operation of a vessel, a first-degree misdemeanour punishable by up to a year in jail. “The prosecutor gave us several options,” says Chuck Viss. “Carter insisted he did not want Stanton to face incarceration. He said, ‘I’d rather have him working with me on ocean safety than sitting in a jail cell.’”

A civil suit was settled out of court, and last November the terms of Stanton’s criminal plea agreement were made official. The court hearing marked the first time Carter and Daniel Stanton Jr. had seen each other since the day both their lives changed.

Leila and Chuck Viss had flown in from Denver. Stanton’s mother, Mary, was there with her son. Stanton Sr. attended via Zoom. Everyone wore protective masks because of the COVID- 19 pandemic. The two families avoided eye contact.

Viss read a victim-impact statement and then Daniel Stanton Jr. addressed him directly. Viss knew that the remorse was genuine and profound. “There was no doubt how he felt,” his father agreed. “You could see the pain in his eyes.”

Judge Robert Panse confirmed the plea deal. Stanton Jr. was sentenced to 75 hours of community service, a year’s probation, a US$1,000 fine and a mandate to work with Viss on legislation to enhance ocean safety and conservation. Afterward, Viss went to Stanton Jr. and shook his hand. Tears flowed and the wall of silence between the families came down. As the two men embraced, Viss said quietly, “Let’s make a difference.”

One of their ideas is a better “diver down” marker. The current design is a red flag with a diagonal white stripe. Depending on wind direction, however, a boater may not see it. Viss favours a bigger, three-dimensional buoy, visible in any weather, with reflective strips.

In addition, Viss wants to see strict speed enforcement. Most boat-strike victims are simply people swimming off the beach. Close to shore, at a popular spot, a speedboat planing at high speed makes no sense.

Has the legal resolution led to forgiveness? “Forgiveness comes from the heart,” says Carter. “I feel like I’m going in the right direction. If I were him and had to live with the guilt and remorse, I’d almost prefer to be in my shoes. It’s a complex thing emotionally, but if I can ease someone else’s pain, I will.”

Next, read the amazing story of how this man was stung by killer bees thousands of times and survived.

I love a beautiful vista as much as the next person, but I have always directed my gaze downward wherever I walk. I like to keep my eye peeled for unexpected treasures—the habit likely goes back to my childhood, searching for fossils in Alberta’s Badlands.

Even today, I partake in my “obsession” (as some of my more charitable family members call it) while walking the dog up and down Toronto’s Don Valley, a river park that spans from Lake Ontario to the far north of the city. Among the numerous small objects I’ve picked up: a 1915 penny, a silver pencil etched with the year 1902 and a lead toy soldier from the First World War.

In January 2019, a few days after an unusually heavy snowfall, I was trudging through the Don Valley as usual with Luna, my loyal but somewhat bored golden retriever. Snow days are not the best for treasure hunting, so I was surprised to see a glint of gold beneath the snow near the bottom of a hill. I carefully extracted a ring of three entwined bands, emblazoned with a Cartier logo.

I walked into the local coffee shop overlooking the hill to see if anybody had reported lost jewellery. Sadly, they had no news, so I headed home to print up flyers to post around the neighbourhood. I also tried a local Facebook group.

I

waited and waited but nobody called to lay claim to my small treasure, and having carefully hidden it from my cat atop my tallest bookshelf, I eventually forgot all about it. That is, until many months later when my wife and I took a trip to Amsterdam to visit our daughter Katie, who was attending university there. I figured that somebody may as well enjoy the ring, so I took it along and was delighted to see that it looked beautiful on her hand. But my daughter’s eyesight is far better than my own, and she soon noticed a tiny inscription on the inside of one of the bands that read, “Omar and Yoshi.”

Right away, she said she could never feel comfortable wearing a ring that was so obviously important to somebody else. I had to agree and took the ring home, vowing to do whatever I could to track down this couple.

Back in Toronto, my son Cameron and I searched through years of wedding notices but there was nothing on record for those two names, and so we began our deep dive into social media. We found hundreds of matching individual names, but never the two together. When something looked even remotely hopeful, we messaged the couple but received only apologetic, negative responses. This was not their ring.

Frustrated, I began to give up hope, then had one last thought: why not call Cartier stores in the city?

Checking online, I saw there were two Cartier stores in the Toronto area. I picked one at random and dialed. An understandably bemused gentleman listened to my story, went silent for a moment and then stated that the ring was totally untraceable. He apologized, and I was about to hang up when he suddenly asked if I had found a name on the ring. I told him just the first name, Omar. “Omar?” he said excitedly. “Omar and Yoshi?”

Nearly a year earlier, two friends of his had mentioned losing one of their matching rings, but, since almost nobody returns lost jewellery, he didn’t expect they’d ever get it back. He gave me Omar’s phone number and I called right away. I reached his voicemail and left a brief message about maybe finding a ring. I waited impatiently for several hours until I finally got the call I was waiting for. Omar was overjoyed, and asked if he and Yoshi could come by to meet me first thing in the morning.

Bright and early, there was a knock at my door and on my porch stood two handsome men in their 30s, with outstretched arms and a bottle of wine. They came inside and we started stumbling over each other trying to tell our respective stories. I explained how the ring had travelled to Europe and back, and only because of that trip had we discovered their names. I showed them the signs I had put up and how we had searched for them in vain.

Before I could hear their story, though, Yoshi slipped on the band and both men triumphantly held up their left hands to show their matching rings. Omar was originally from Colombia and Yoshi from Mexico. They had met in Toronto and married the previous December at a small ceremony where they gave each other these rings. Just a few weeks later—after the first snowstorm of winter—they decided to do something truly Canadian and bought a toboggan, carrying it to the steep hills of the Don Valley, right at the end of my street.

Their first run was spectacular, fast and very scary. As they pulled themselves up out of the snow at the bottom of the hill, another toboggan smashed into the two, sending them cartwheeling across the field. They hobbled back up the hill and straight to a hospital’s emergency room department to set Omar’s broken arm. It was only then that they discovered Yoshi’s new ring was missing. Heartbroken to have lost it so soon after their wedding, Omar went back to the hill the next day to search, but it was hopelessly gone, or so it seemed.

I now have a great photo of the three of us in my house, with our arms around each other’s shoulders and their hands raised to show off the rings. We stay in touch and, honestly, I can’t imagine a more quintessentially Canadian love story.

Next, check out these random acts of kindness that will inspire you to pass it on.

I belong to the camp that has survived COVID times by staying up very late at night to avoid my two children (and my ex, whom I live with in Toronto, which seemed like a better idea before we became trapped in the same space for over a year). At least, I assume there are others out there like me, reading this during their 4 a.m. lunch break. The silent nighttime hours can be great for concentrating on a task without interruption, but also lend themselves to bizarre trains of thought: the sort of things that might have been dreams, if not for my nocturnal schedule.

One of the questions I pondered during these past 15 months of extremely strange sleep patterns is: if “Ring around the Rosie” is purportedly about people dying of the bubonic plague (we all fall down—get it?), then what rhymes are my daughters and their friends making up about the current pandemic that will seem harmless if slightly mysterious in a few hundred years? Since encountering this factoid about “Ring around the Rosie,” I’ve treated all children’s rhymes with a bit of suspicion.

Another late-night obsession was why children’s rhymes so often talk about ants being in your pants, like Dennis Lee’s poem, On Tuesdays I Polish My Uncle, and at least a dozen children’s songs. There are so many other words that rhyme with “ants.” The ants could dance in France, or have a great romance on plants. Is it really so common to have ants in your pants that it deserves the status of being a common motif? Or is it a euphemism for something much more sinister? These are some of the questions I attempted to research with the energy of a QAnon conspiracy theorist.

I recently stumbled upon an answer to at least one of these questions. Due to lockdown restrictions, many local restaurants have closed, and the downtown rodent population has moved off the main streets and into residential areas. At first, I thought the quality of plastic food packaging had gotten worse, then realized that the holes in the oatmeal bag had a more organic source: mice. We’ve now had mouse traps set up in our kitchen for months, and my six-year-old has made a sizeable rodent cemetery in the backyard with headstones made of bejewelled popsicle sticks, dandelion bouquets and names for each victim. Rest in peace, Nibbles. I can’t say that I’ll miss you, but I do admire your nerve.

After one adventure, when the elusive black mouse and I caught each other sneaking into the kitchen for a 2 a.m. snack, and I heroically tricked it into running into a trap, the rodents were finally wiped out. Unfortunately, a colony of ants quickly took over the job of licking off the peanut butter from the rest of our traps, so we now have an ant infestation.

Even in those precious moments when all the human inhabitants of the house are asleep, and I’m still awake for no other reason than the thrill of being alone, I’m never really alone. One morning, as I was sitting down for a pee, a little bleary after staying up binge-watching Korean soaps (with the flimsy justification that it might help me learn a new language), an ant brazenly walked across the toilet seat between my splayed legs. I jabbed at it with my thumb, trying to squish it, but only succeeded in knocking it off the toilet seat. It fell into my pants, waiting just below.

Next, read this hilarious tale of a family RV trip gone wrong.