For many of us during the pandemic, the world was turned upside down and we completely changed our notion of what was “normal.” Many felt alone or possibly forgotten, while others suffered loss. Not being able to touch or talk to our loved ones face-to-face was so difficult.

All that pain and upheaval made me think of last Remembrance Day and the changes that were put in place. For 20 years, I’d gathered outside with others to quietly reflect on the sacrifices made by so many, and show gratitude for their gift of freedom to us all.

I cherished being able to see, and shake the hands of those who served and are still serving to keep us safe. The energy in these crowds was amazing. We were all there to honour, remember and stand together in reflection of what was sacrificed for us. Regardless of the weather, I wanted to be there and show my gratitude and support. I always thought that if those who served could endure all sorts of weather and situations, the least I could do was bundle up if need be and stand for 45 minutes to honour them. It was a small gesture on my part but one that I felt was important.

The year 2020 changed those plans and I was really upset at not being able to gather downtown at the cenotaph. This lack of gathering affected me more than any other inability to get together with anyone. It made me start to think of other ways that I could still honour those who served.

The isolation we were all feeling gave me a small glimpse into what they must have felt, being away from home and those they held dear. They were put in unfamiliar places facing an uncertain outcome and forced to carry on. Did they feel forgotten? I am sure they must have. Were they unsure of any positive outcome? I bet they were. Still, no matter what they felt, they stayed the course and persevered through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. I would like to think that they held onto the hope they would see their loved ones again. If they had to sacrifice their lives, it would be so they could help those they loved to live and be free and secure.

I wanted to find a new way of honouring those who lost their lives. I requested a map for the placement of soldiers in the Red Deer Cemetery, which is close to my home. I drove there with my husband, Dave, and we walked through the fresh snow to the rows of those who gave their lives and placed a poppy on as many of the headstones as we could.

Standing there gazing at those rows of graves, the sun peeking through the trees, we held our own moment of silence for them. I read their names, and I said thank you to each of them. There was no music, no speeches, no mournful trumpet calling out. Just us, taking a quiet moment to say thank you for your service, you are not forgotten, you are loved.

In a world that seems so changed now, hold onto what you can. Show your love and support to all. Remember that you are not alone. There is someone who loves you and wants you to be well. Together we will continue to move past this time and enjoy gathering and celebrating being able to hug, sing and cheer again.

On November 11, I hope you are able to take a moment to reflect on those who fought for us and honour their memory, whether you knew them or not. They gave the ultimate sacrifice for us all and they deserve to never be forgotten.

Next, check out these 30+ powerful true stories of Canadian veterans to read for Remembrance Day.

It’s odd sometimes how we make connections with the living and the dead. One of the most striking I made was with First World War soldier Mervyn Naish in 1987, when my wife bought an antique dining room buffet at an auction in Barrie, Ontario, some 70 years after he died.

A week or so after she brought it home, it still sat in the garage. When I examined it, I noticed a document lodged at the back of one of the drawers. The paper was yellowed with age, the same colour as the wood, and might have been easily missed.

I retrieved what turned out to be an original Canadian Expeditionary Force death certificate for Mervyn Naish of the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade. The certificate, dated 1917, was rather ornate, not large, maybe 20 by 30 centimetres, with the details written in fountain pen. I held it carefully because I was holding a piece of history that I knew didn’t belong to me. Mervyn had died of his wounds, which means he likely suffered before he expired. I knew I had to return this certificate to someone connected with the fallen soldier.

I began by checking the war memorials in Simcoe County, just north of Toronto, not far from where the auction was held. The area is full of small cities and towns. As a lawyer, I often attended satellite courts throughout the county, and on my way home I would check each town’s memorial. I had never before scanned the long, sad lists of names carved in stone, and the experience was sobering. Each one had been a man who was someone’s son, or brother or husband.

Mervyn Naish, however, was not one of the names I found. He was proving to be elusive.

Finding Mervyn

Discouraged by my lack of success, I lost interest for a few months. But one rainy morning I was racing to court in Penetanguishene, Ontario, when I spotted a memorial in the village of Waverley, which I hadn’t seen before. I stopped on my way back and scanned the list of casualties.

Among the fallen soldiers of Medonte township was the name Mervyn Nash. Although the spelling of his surname was different, I felt sure that this was the right man. Later that day I checked the phone book for the area and came across another Mervyn Nash. I didn’t believe it at first. I reread the entry several times. I felt a mixture of shock and relief, as I knew this must be the family.

Instead of calling the number, I decided I would just drive the certificate over to them.

The following Saturday, I placed the certificate in a legal file folder and headed to the township where Mervyn Nash lived. It was a sunny spring morning. I stopped at a variety store and asked the fellow behind the counter if he knew Mervyn Nash. He did, and gave me directions to his farm.

As I turned into the yard, I realized I’d been looking forward to this moment. I walked up to the house and could see someone at the kitchen table through the screen door. I knocked.

The middle-aged man stood up and I could see he was dressed as if he’d just come in from working outside. He was wary of this stranger at his door.

“Are you Mervyn Nash?”

When he said yes, I pulled out the document and handed it over. “I think this belongs to you.”

I watched him mouth the words as he read, and when he looked at me, he was overcome, unable to say much except that he wanted to know who I was and how I had come into possession of this certificate. I explained my story, then asked him for Mervyn’s.

A Walk Through History

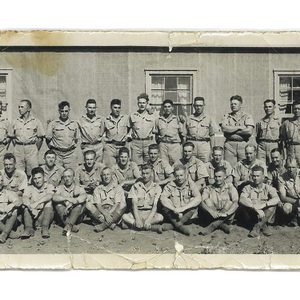

The man I was speaking to had been born about a decade after the end of the First World War and named in honour of his fallen uncle. Uncle Mervyn had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Orillia, Ontario, in February 1916. Because he was underage, he used a false name and date of birth. The soldier died in Noeux-les-Mines, France, a year and a half later, on August 8, 1917.

Mervyn brought me inside and showed me his uncle’s photograph taken shortly after his enlistment. Mervyn had been entrusted with the soldier’s medals and postcards but had never seen the death certificate.

Mervyn and I spent the morning together. We walked around the farm, noting where the Coldwater River flowed through and where the salmon came in from Georgian Bay to spawn. Everything was green and lush—a beautiful and tranquil setting. While we spoke, we both thought of the young soldier who had been born and raised in Creighton, Ontario, and who had never returned from the war. Every few moments the conversation would naturally return to him. I asked Mervyn about the misspelling of the last name and was told that it actually had a significance of its own.

Back at the house, Mervyn showed me old family records he kept hidden away in a bible and explained to me that the family name was once spelled Naish. It was changed to Nash a few decades after the family had immigrated to Canada from England in the 1830s. The young soldier had used his old surname in order to get around the local recruiters, who would have known the Nash family and that Mervyn was underage.

Before I knew of Mervyn Naish, Remembrance Day was never personal. I never had a relative killed in any war. But every November 11th since then I have thought of him during the minute of silence and when the bugle is sounded. I imagine that he, like many others, was a boy in a hurry to get off the farm, into a uniform and off to Europe, before all the excitement ended. I have thought of the sorrow that would have befallen his family when they received word of his death. I can only think that this certificate was too painful to look at or to hold, and so became lost in a hidden part of a drawer, and then forgotten with the passage of time.

But this is one young soldier’s story that needs to be remembered.

© 2018, Michael Shain. From “Remembrance Day Was Never Personal. Then I Learned About Mervyn Naish,” from The Globe and Mail, (November 4, 2018), theglobeandmail.com.

Next, check out 30 powerful Remembrance Day stories from Canadian veterans.

A reluctant hero

June 6, 1944, 19-year-old Harold “Rowdy” Rowden (my father) stepped into the cold water of the English Channel at Juno Beach and became part of history. It was a day that played a large role in changing the outcome of the Second World War and the course of history.

Alongside Utah Beach (the American landing zone), the assault on Juno is widely considered the most strategically successful of the D-Day landings. Juno Beach, a 10-kilometre stretch of French coastline, was one of five beaches in the Allied invasion of German-occupied France known as the Normandy landings. It was primarily the responsibility of the Canadians to take Juno with some air power, sea transport and mine sweeping being provided by other Allies.

It’s said that the code name Juno arose because Winston Churchill considered the original name—Jelly—inappropriate for a beach on which so many men might die. He insisted on a change to the more dignified name of Juno.

As a young boy growing up in Port Hope, Ontario, Harold never imagined that he would one day travel to Europe to fight with 90,000 other Allied soldiers in the Normandy Invasion to oust the Nazis. He’d signed up at 15 years of age because there was “nothing going on in Port Hope” and he’d make $1 and 10 cents a day—a hefty enough sum in those days. He was assigned to the 3rd Division of the 13th Field Regiment and trained to be a dispatch rider.

Training in Scotland helped prepare Harold for battle and for following orders, and it changed him from a boy into a man. On June 5, 1944, at Southampton, England, when he boarded his ship for the trip across the Channel, he began to truly understand what he would face. The Channel was rough, with waves two metres high, which made the crossing very difficult. The ships, landing craft and men were tossed around so much that many of the young recruits became violently seasick. By dawn, the weather was still bad, but the landings were a go. In preparation, destroyers began pounding the German coastal defence positions, while the bombers overhead dropped thousands of tons of bombs. Everything was on fire—the sky and the entire coastline. Harold thought it must be like hell. The noise was deafening as thousands of engines roared and bombs exploded around them; the air the men breathed was crackling and filled with smoke.

Against all odds

General Eisenhower’s voice came over the loudspeaker and told them, “You are about to embark on the Great Crusade… The eyes and ears of the world are upon you.” Their training had involved firing a gun with no one firing back; now Harold and his comrades were about to face a battle-hardened enemy. It was into this mayhem that Harold entered when the landing ramp dropped and he began the deadliest run of his life to the sound of a loudspeaker blaring, “Get off the beach, get off the beach!” As well as coping with the rough and cold waters, there were obstacles and minefields to be avoided. Sadly, many young men didn’t even make it to the shore; they drowned before they even started. Harold, with his bike, and his comrades waded ashore and directly into the killing zones of the German gun positions. The Germans were shielded by the brick seawall and many Canadian soldiers were gunned down in the water or on the beach. It was hard combat and the soldiers used raw courage, grenades, rifles and bayonets to storm the German nests.

The brave Canadian soldiers didn’t hesitate to advance despite the loss of countless numbers of their platoons. Through the terror of battle, they found the courage to keep going. Fourteen thousand Canadians stormed Juno Beach on D-Day and their bravery and achievements were remarkable. By the end of the day, they had progressed further inland than any of their allies and had smashed the first line of German defences. Harold fought beside his friends, people he had signed up with, lived with and trained with, and they found the courage to endure the fierce and frightening battle. They had hundreds of casualties, wounded and many others taken prisoner, but ordinary young Canadian boys accomplished what many had thought was impossible.

Harold went ashore near the town of Courseulles-sur-Mer and once the beach had been secured and the advance inland began, his “job,” as a dispatch rider, truly began. His task was to transmit coded messages to his commander from various observation posts. He was a vulnerable target, riding out alone multiple times a day on his Norton motorbike—easy pickings for any sniper.

After only a few days in France, Harold’s regiment again came under direct attack. He was knocked flat by a deafening, violent concussion and when he staggered to his feet he found four of his comrades dead and his commanding officer on the ground, bleeding profusely from a piece of shrapnel through the neck. With only the field dressing he had stuffed into his helmet, Harold covered the wound and applied pressure until help arrived—he is credited with saving his officer’s life.

On July 29, at the Battle for Caen, during intense enemy shelling, Harold was hit with a blast and thrown against a truck, losing consciousness. He only remembers waking up in a field hospital. His left leg was completely mangled, with the tibia busted to bits. Harold doesn’t know how the doctors coped that day as soldiers were being bought in by the hundreds, many bleeding profusely with serious wounds. Many had their legs or arms blown off; Harold was unable to walk but he was alive! His service to his country was over.

In December 1944, he was transported across the Atlantic aboard the SS Letitia, an ocean liner turned hospital ship. Back in Ontario, he spent six months in Kingston General Hospital as his wounds healed.

Aftermath

Since participating in the D-Day raids of 1944, the 93-year-old veteran has been back to France six times, mainly to Juno Beach. His name is among those of veterans engraved on the monuments in front of the Canadian Juno Beach Centre in Courseulles-sur-Mer—the same beach where he went ashore all those years ago. Harold has eight medals for his service, with the latest being France’s highest honour, the rank of Knight of the French National Order of the Legion of Honour. France has never forgotten the sacrifice of those Canadians who went to liberate French soil.

My siblings and I are very proud of our father. He doesn’t like to talk about the war and has never considered himself a hero. He says he did only what was asked of him and he’d do it again to help protect his country—a land as magnificent as Canada. He says he’ll answer questions when he needs to, but “there’s no glory in killing a man, you just try to get it out of your mind.”

Check out more Remembrance Day stories from Canadian veterans.