My parents landed in Canada from a small town near Naples in February 1969. They’d sold their only real possession—a bedroom set—and arrived with $200 in their pockets. They faced harsh, snowy winters for the first time and worked hard at whatever jobs they could find.

I grew up in a tiny apartment in the multicultural neighbourhood of Mimico in Toronto. My family was open, curious and inclusive. To me, being Canadian meant that we were the total sum of our parts. Still, I shared some of my parents’ feelings of loneliness and displacement. I went to kindergarten speaking mostly English with some Italian sprinkled in, but I was not amongst the majority in school, and I was constantly being reminded by the class bullies that I was not Canadian. I recall being told to go back to my country—yet Canada was my country. I was born here. This experience instilled a sense of deep disorientation, and I struggled with this identity crisis for much of my life. I would even hide in the bathroom to have my lunch for fear of being ridiculed or, worse, beaten up.

To add to my confusion, my family and I would travel to Italy in the summers to visit relatives. As much as Italy felt familiar and comforting, I did not fully relate to its way of life and culture. Like so many hyphenated Canadians, I felt as though I was split between two worlds, and I longed to belong somewhere.

Over time, my mother became a successful entrepreneur and my dad a powerful figure in the labour movement. We were encouraged to assimilate and respect the Canadian way of life. My parents valued education, and my father believed that getting a secure job with a pension was the only way to be successful and fulfilled. He felt it was important to slowly build security over a lifetime, without taking too many risks. My mother, on the other hand, was more of a calculated risk-taker and artistically inclined. She loved music and enrolled me in lessons when I was five, which set me on a very different path from the one my father had envisioned for me. Even now, music plays such a big part in my process. From the moment of inception of every film, I think about the score, the melodies, mood and tone.

Finding Film

I quickly learned that music—then later film and the arts in general—would be my escape. I will never forget watching my parents’ eyes light up as I performed at my vocal recitals. It reminded me of the times they would laugh joyously or be deeply moved watching movies at the San Carlino cinema in the Italian section of town, which we often visited on weekends. Whether it was a recital for the Royal Conservatory of Music, a magic show in my backyard where I would charge neighbourhood kids 25 cents, a talent show where I would impersonate Prince or an elaborate school play, I fell in love with using the arts to create an emotional response in people, especially the ones I loved most.

I also wrote scripts as a kid, mostly stories that mimicked the films I loved at the time, such as E.T. and Star Wars. My father owned a Super 8mm camera I played around with. The most state-of-the-art equipment he owned was a VHS camera and recorder that was so heavy, I sometimes wonder how I managed to drag it to family vacations. My dad loved to tinker with technology, and I remember how exciting it was to film something, wait several weeks to have it processed and then set up a screening at the house on the projector for friends and family. In an era before Skype and Facetime, I remember seeing 8mm film of relatives in Italy sending messages and greetings. These were highly emotional moments in my house.

As a teen and into my early 20s, I owned several businesses, including a retail store that featured my own fashion line, vintage clothing and Canadian designers. I owned a club promotion company as well as a landscaping company to make extra money during the summers. I organized fundraisers for the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation and the local food bank. I joined a band in my teens, and we performed original songs and covers. Later, after performing at several smoky bars and hosting karaoke nights, I launched a record label of my own called Trinity Records to help promote other artists. My varied experiences over the years helped me develop skill sets that would eventually inform my work in ways that I could never have predicted. My experiences also helped me build the courage I would need to take creative risks, and the willingness to do things that at first blush might seem unreasonable.

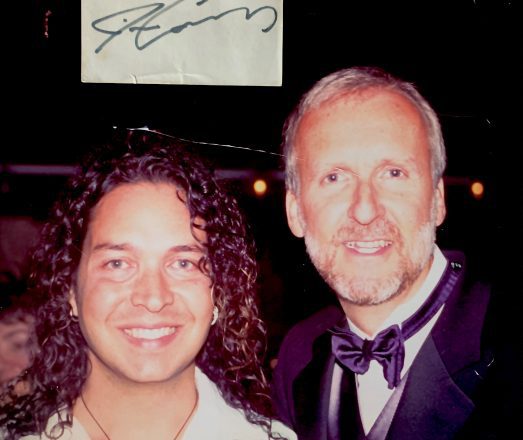

Although I had dreams of becoming a filmmaker, I did not have any direct connection to the industry as a young adult. I didn’t know anyone who worked in movies, and there was no clear path to achieving such a goal. Certainly, like many children of immigrants, I thought movies were only made in Hollywood. It wasn’t until I travelled to my first film festival, determined to meet director James Cameron, that my journey would start to become clear. It was at the height of the Titanic frenzy, and Cameron was attending a homecoming presentation at a small festival in Niagara Falls. During his opening speech, he remarked that growing up in a small town in Canada was a far cry from Hollywood—until he went there and realized that everyone put on their pants one leg at a time. It was as if he were speaking to me. I turned to my friend and said, “I’m going to meet James Cameron.”

Mobs of fans and journalists waited outside. He was whisked away by handlers, and by the time I saw Cameron enter his limo, my dream of meeting him was dwindling. Feeling dejected, we walked to a hotel to use the bathroom. As I ambled around the corner of the parking lot, the door opened, and there was James Cameron himself.

“Hey, James! I want to be a filmmaker,” I blurted.

He replied without hesitation: “Then pick up a camera and shoot something.” We both laughed. He posed for a photo and off he went.

His advice was simple, and it ignited something in me I will never forget. Here was a small-town Canadian boy who had made the biggest movie of all time, winning 11 Oscars, telling me I could do it. Why wouldn’t I believe him? I was young and naïve, and the cynicism of the world had not yet set in. Suddenly, anything was possible.

From Hogtown to Hollywood

Meeting James Cameron set in motion a chain reaction of serendipitous encounters with many of my Hollywood heroes. Most recently, Alexander Payne graciously talked me through the prep stage of my latest film, The Cuban. His advice was clear and simple: tell the truth when communicating with legendary actors like Louis Gossett Jr. and become an observer.

Being part of a community of like-minded individuals is the most gratifying part of the business. The fact that I can meet filmmakers from anywhere and speak the universal language of cinema brings the world closer together. Film becomes a window onto the world where we can share common (and not so common) experiences.

Whether they know it or not, each of my mentors played a role in continuing to inspire me in my darkest hours. I learned that words matter, and what we choose to say to each other matters. For this reason, I now dedicate some time to mentoring emerging filmmakers, and I am mindful of how impactful my advice can potentially be. Sometimes all a person needs to hear is that their voice matters and to never give up. Beyond technical guidance, artists need to know that people before them have experienced the same struggles. It sounds cliché, but I am living proof that giving someone a boost is better than a kick in the ass, as legendary Canadian entertainment journalist Brian Linehan once told me.

When I made my first film, Over a Small Cup of Coffee, it was shot on 35mm film, and everyone on set had little to no experience— myself included. The elation of the whole experience was inexplicable, from the very first meeting at a bar in downtown Toronto, where over 100 people showed up to volunteer, to the arduous shooting. The film premiered at the iconic Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, and as I looked around the sold-out screening, I saw actors I admired, such as Dom DeLuise and Vincent Schiavelli.

This past year gave me a lot of time to reflect upon and realign my values and priorities. We developed a new way of releasing movies during a pandemic, and with our distributors released The Cuban in over 50 cities in the U.S. via virtual cinema, and in drive-in and indoor theatres across Canada. Our virtual press tour lasted months, and we even ran an Oscar nomination campaign, all from the comfort of my home office. The whole experience was not only a dream come true, it far exceeded my expectations.

Creating meaningful content that has the potential to make an impact is crucial to me and aligns with the mission statement of my production company, S.N.A.P. Films Inc. Giving back and supporting fellow artists at all stages of their careers is also a big part of my mission, and this journey has led me to develop and launch my new podcast, Creativity Unleashed. Intended to be a resource for creatives, it will help people learn from high-level performers and coaches in all sectors, even outside entertainment. Everything I continue to develop feeds my burning desire to foster my creative spirit and, most of all, continue to entertain people and make them feel something.

Next, check out the best drive-in theatres across Canada.

If a person is not breathing, his heartbeat will stop. Do CPR (chest compressions and rescue breaths) to help circulation and get oxygen into the body. (Early use of an AED—an automated external defibrillator—if one is available, can restart a heart with an abnormal rhythm.

First, open a person’s airway to check if they are breathing (don’t begin CPR if a patient is breathing normally). Then, get help. If you are not alone, send someone to call for help as soon as you have checked breathing. Ask the person to come back and confirm that the call has been made.

CPR 101: These Are the CPR Steps Everyone Should Know

1. Position your hand (above). Make sure the patient is lying on his back on a firm surface. Kneel beside him and place the heel of your hand on the centre of the chest.

2. Interlock fingers (above). Keeping your arms straight, cover the first hand with the heel of your other hand and interlock the fingers of both hands together. Keep your fingers raised so they do not touch the patient’s chest or rib cage. (Check out these emergency first-aid kit essentials.)

3. Give chest compressions (above). Lean forward so that your shoulders are directly over the patient’s chest and press down on the chest about two inches. Release the pressure, but not your hands, and let the chest come back up.

Repeat to give 30 compressions at a rate of 100 compressions per minute. Not sure what that really means? Push to beat of the Bee Gees song “Stayin’ Alive.” (Learn how to recognize the silent signs of a stroke.)

Note: The American Heart Association recommends Hands-Only CPR (CPR without rescue breaths, which are detailed below) for people suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. According to the AHA, only about 39 per cent of people who experience an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest get immediate help before professional help arrives; doing Hands-Only CPR may be more comfortable than doing rescue breaths for some bystanders and make it more likely that they take action. The AHA still recommends CPR with compressions and breaths for infants and children and victims of drowning, drug overdose, or people who collapse due to breathing problems.

4. Open the airway (above). Move to the patient’s head. Tilt his head and lift his chin to open the airway again. Let his mouth fall open slightly.

5. Give rescue breaths (above). Pinch the nostrils closed with the hand that was on the forehead and support the patient’s chin with your other hand. Take a normal breath, put your mouth over the patient’s, and blow until you can see his chest rise.

6. Watch chest fall. Remove your mouth from the patient’s and look along the chest, watching the chest fall. Repeat steps five and six once.

7. Repeat chest compressions and rescue breaths. Place your hands on the chest again and repeat the cycle of 30 chest compressions, followed by two rescue breaths. Continue the cycle.

Next, learn how to recognize the silent signs of a heart attack.

The sourdough spree was fun for a while, but more than a year into the pandemic I find myself drawn to more modest tasks. Tiny triumphs that offer clear resolution. And I do mean tiny. For instance:

Cobbling. The other day, I retrieved a pair of vintage, rhinestone-trimmed stiletto mules from my closet. The soles had begun to peel away, so I glued them back on, clamping the heels in a vise to dry. It’s not often you see rhinestones in a vise. Then I put the shoes back in the closet. As long as I know they’re there, the history of parties is not over yet.

Sorting. I took about a hundred dessert forks out of my cutlery drawer, bagged them, stored them in the winter-hat bin, probably forever, and felt a glow of accomplishment.

Testing batteries. Yesterday I retrieved a quaint gizmo we own that measures the charge left in a battery. It’s gratifying to see the little needle leap up into the green zone, meaning that the battery in question is still fresh and usable. It is not dead, in other words. Good news!

Taking down the Christmas lights. Yes. It’s time.

Washing the car mats. If the prospect of waiting in line for a car wash tires you, hosing down the car mats will give you some small peace of mind.

Throwing out spices. If you have a jar of ground coriander with no detectable taste or odour, this doesn’t mean you have COVID and you can’t smell; it means it’s old and you should throw it out. This decision will give you 15 seconds of satisfaction before you find yourself staring at the many boxes of stale herbal teas you never drink.

Darning. I don’t knit, which is a popular pandemic activity, but I will darn. Moth holes in sweaters are depressing because they represent more proof (we now have lots) of an indifferent nature. Like viruses, moths also infiltrate and are difficult to banish. Darning is an uplifting investment in the future. It suggests that you are looking forward to another 10 years of wear out of that sweater.

Clearing your inbox. This is more than a tiny triumph. It’s major housecleaning. Clear your search history, too. It will only remind you of how often you googled “Celsius to Fahrenheit” when taking your temperature, or “Is frequent eye blinking a COVID symptom?”

Changing your filters. Have yourself a fun filter day: don’t just scoop out the lint filter in your dryer, wash it with soap and water. And wash the horrible little filter in your vacuum cleaner. There is also a little-known gunky food filter in most dishwashers. Clean that, too. Then wash all your face masks and hang them up like clothing for mice.

Organizing your photo albums. If you have more than eight photos of the dog wearing reindeer antlers at Christmas, throw out five. Then go watch TV.

Thanking a stranger. You probably know someone doing a good job under difficult circumstances and without much recognition. Maybe it’s a courier who regularly comes to your door or a friend who works in health care or a woman who offers free dance classes online. Let them know you appreciate their work. A tiny gesture of gratitude will improve their day and yours, too. Remember, no task is too small.

Next, check out 30 things you can organize in under 30 minutes!

Many parents are vigilant about their kids’ use of electronic devices and set strict limits for them. Of course, they want to protect their children from the potentially harmful effects of too much screen time, as well as other potential dangers they can encounter on apps and online platforms. But there’s another device-related danger that parents may be completely overlooking—and it might be hurting their kids just as much as traditional screen time.

Shining a light on the issue of “secondhand screen time”

It’s been dubbed “secondhand screen time.” And yes, it’s meant to mirror the danger that we now know all too well in regard to secondhand smoking. With secondhand screen time, kids are indirectly exposed to screens being used by someone else close to them. “Generally, we are talking about children who are cared for by adults who spend a significant amount of time on devices and the negative consequences that can occur when they experience screens being such a dominant part of the adult’s life and activities,” says Nicole Beurkens, PhD, a clinical psychologist and the brand ambassador to Qustodio, a parental control app designed to manage kids’ online activity and keep them safe. “Some of the specific concerns involve the addictive nature of devices and how watching parents use devices constantly from a very young age can make kids more prone to addictive behaviour with devices as they grow.”

This can also lead to behaviour-related problems. “Research shows that children have a tendency to exhibit more acting-out behaviours when parents spend excessive time with their devices,” explains Beurkens. “Often, this is the only way kids can get a parent’s attention, even though it typically ends up being negative attention. Excessive device use, especially in the presence of a child, also sends the message that the device and activities on it are more important than the child. This can lead to a breakdown in the parent-child relationship, as well as self-esteem and other emotional issues for the child.”

So, how much screen time is too much?

It’s important for parents to be conscientious about placing limits on electronics, both for themselves and their children. “The American Academy of Pediatrics has issued guidelines for screen time and children from infancy through the teen years,” says Beurkens. “The general consensus is that young children should have very little exposure and only high-quality programs they view with an adult. As they get into the preschool years, the general guideline is one hour per day of high-quality activities/programs. Children in elementary school should not be spending more than two hours of their leisure time on devices and should have a balance of other activities they engage with as well. As children get into the preteen and teen years, the focus should be on prioritizing non-screen-time activities and using devices in free time as opposed to constantly.”

When parents are engrossed in something they are watching on their phone or other devices, they also may not realize that a child nearby may be paying attention to what’s happening in the background. This means they may be exposed to violent or mature content or fast-moving images that are overly stimulating for young brains. This can cause an increase in anxiety and sleep issues, as well as make it more difficult for kids to unwind and settle down when it’s time for bed. (Find out more night time habits that sabotage sleep.)

Focus on quality time

There’s another thing to consider: The more time you spend looking at your electronics, the less time you can devote to giving your kids your full attention. And that’s something they really need. “A child’s cognitive, communication, social, and emotional development happens via their relationships with parents and other care providers,” says Beurkens. “When devices consistently get in the way of the quality relational experiences children need, their development can suffer. This doesn’t mean that parents should never use devices when a child is present. It does mean that parents need to be aware of how often they are fully engaged with their child without devices and make sure there is quality interaction and attention being provided.”

Obviously, exactly how involved a parent can or should be in their child’s daily life will vary depending on the age of the child. But letting your child know that they are your priority and will get your full attention when needed is always important. “This means secondhand screen time is an issue parents need to be aware of regardless of their child’s age,” says Beurkens. “In terms of brain development, the impact of excessive parental device use is probably more pronounced from infancy through early childhood, as this phase of development is where the consistent engagement with parents is most necessary for proper cognitive, communication, social, and emotional development.” While the issues change as kids get older, they still need to know they have your undivided attention, especially as they attempt to navigate new social and emotional challenges. (Concerned you might be addicted to social media? Here’s expert advice on how to unplug.)

Establish reasonable limits

Secondhand screen time has only been getting attention fairly recently, so there are no concrete guidelines yet. “To my knowledge, no one has issued recommendations for secondhand screen time, although the general consensus among child-development experts is that parents/caregivers should prioritize focused engagement with the child over distraction with devices the majority of the time,” says Beurkens. “Children require engaged face-to-face interactions with parents and other trusted adults in order to support proper brain development. Excessive screen use by parents gets in the way of this and should be minimized whenever possible.”

Use your discretion and judgment to determine limits for your own gadget usage, just as you would for your children. Also, take cues from your kids. If they seem to be frustrated because they’re constantly trying to get your attention when you’re focused on electronics, that may be a red flag that you are overdoing it.

Setting the right example

There’s also the matter of the confusing message you may be sending to your kids with a “do as I say, not as I do” approach. “We can tell kids that it’s important to curb their device use, but if their experience with parents from infancy on is watching them use devices frequently, they are much more likely to follow that model,” says Beurkens. (Discover the hidden downside of your social media obsession.)

This may not be easy

Managing a child’s use of electronics can take effort. But trying to cut down on your own screen time may be even more challenging. “For adults, this issue can be trickier because devices are often a necessary component of people’s work, as well as personal tasks and activities,” says Beurkens. “Being aware of whether time on devices is interfering with other important life activities is helpful. A good general rule of thumb is to ensure there are at least some periods of time during the day (and definitely at bedtime) when devices aren’t being used. That’s a helpful way to start establishing more balance.”

Actions to take now

While this may not be easy, it is worth the effort. And there are manageable steps you can take now to get started. “One of the simplest is establishing certain times and places where devices won’t be used,” says Beurkens. “For example, device-free mealtimes are important for many reasons, and this is an easy way to curb use. Other ideas include not using devices in the restroom, when having a conversation with someone, or when playing games with the kids. Turning off as many notifications as possible is also very helpful, as we have less of a tendency to constantly be checking our phones when our attention isn’t constantly being drawn to every ding or vibration.”

There are even ways that you can use technology to your advantage in this regard. “Using the screen time monitoring features on devices allow adults to become aware of how much time they are spending on devices and what activities they are engaging in,” says Beurkens. “There are many apps that people also find helpful. Qustodio is a great one for managing and monitoring children’s use of devices, and some parents find they benefit from using it on their devices, as well.”

Next, find out how to break up with social media through a 10-step digital detox.

Ping & Gaston

Over the past year, I’ve found myself justifying all manner of what you might call non-essential purchases in the name of lockdown.

I ordered a hand-knit cotton sweater from Spain and throw cushions from Sweden, but the most delightful and, um, let’s say, unusual thing I “added to cart” was a pair of Pekin ducklings.

This happened last June, when my husband, Joaquin, my five-year-old son, Leo, and I were in month three of lockdown. By then, I had long shuttered the charade that was our home school, and there were no summer camps and no play dates. If there was a playdate, I was the playmate—and I was exhausted. Even our two cats seemed increasingly oppressed by our constant presence, pining for Precedented Times, when the house was their private hotel and humans would only occasionally pop in, like housekeeping.

So there I was scrolling Instagram, retreating into the seeming perfection of other people’s lives, when I spotted a friend’s photo of two tiny golden ducklings in her living room. I messaged her immediately. She explained that she was fostering the babies for a farm in rural southern Ontario. You can adopt the newborns and parent them as long as you like—typically, the farm explains on its website, the usual foster lasts a few weeks, until the ducklings waddle from their downy infancy into their more obstreperous, feathered teenaged fowl-hood. This program helps fund the farm and, I told myself, generously provides us with what we’d been lacking: joy, spontaneity and fellowship.

“We’re getting ducklings!” I proudly announced. Joaquin replied with something along the lines of “What?”

I explained that, for $165, the farm would bring us everything we needed—“chick Gatorade,” a heat lamp, food and bedding (a bale of pine shavings) and also an activity for Leo.

“Okay. When do we get them?” he said gamely, at which point, I smugly concluded that I had married wisely. “You never really know a man until you’ve divorced him,” said Zsa Zsa Gabor. Yes, or until you’ve adopted livestock together in a pandemic.

About 10 days later, on a sunny June morning, a man from the farm arrived at our downtown Toronto doorstep. In what will remain the best delivery moment of my life, he handed over a shoebox housing a pair of newborn chicks.

Leo and I held them in our hands, each one a tiny, almost weightless parcel of silky gold. Their webbed feet, clementine-orange, felt soft and satiny against our palms, and their glossy little beaks were unexpectedly warm. Leo immediately cast himself as their father, and they accepted the role happily, waddling at his heels and slipping on our hardwood floors, like Bambi on an ice rink. He decided to call one of the ducklings Gaston, after his favourite cartoon character, and I named the other one Ping, after the Chinese duck hero from one of my favourite childhood books.

Leo kissed Ping and Gaston on their beaks and they nipped at his lips, which he concluded meant they loved him. He then decided that they must need a bath after a long trip from the country. He filled a Tupperware bin with water, which filled me with a surge of relief. (It was an activity! Without an iPad!). So much of parenting, especially pandemic parenting, comes down to guilt management. And our new family members delivered me from mine. When Leo lowered them into the bin, they took to water like, well, ducks. Afterwards, we swaddled them to keep them warm.

If the pandemic had plunged us all into chaos, at least this kind had a madcap charm. The messiness was, also, literal, of course. For the ducks, the world is not so much a stage as it is a toilet—you can’t house-train a duck the way you can a dog. I had read that as a foster duck parent, you can fashion tiny diapers. One surely could do such a thing, but I did not. And while Leo was happy to share love and Cheerios, he swiftly made himself scarce when it came to the dirty work.

“It’s okay, Mummy, I’ll let you clean that mess,” he’d so generously offer. At this point, while serving as parent, cook, playmate, cleaner and head butler to Leo, I also had duck husbandry to add to the list.

After a few weeks, the ducklings at least tripled in size, and the fairy tale took a turn. As much as we loved Ping and Gaston, they’d become an armful, and I began to think it was time to return them. It was only then, however, that I realized that I didn’t know what would happen to them back at the farm. When I called to find out, the woman on the phone, annoyed by this line of inquiry, tersely suggested that I refer to the last page in my “duckling manual”—a beak-orange folder that had arrived with our pets. In fine print, I read to my horror that they’d likely serve as a “wonderful supper” at a wedding or a banquet. We had been fostering these animals, hadn’t we, not fattening them for a meal?

We couldn’t keep them, but I also couldn’t drive them back to their demise. And this is how I found myself launching a sort of duck-adoption agency, frantically emailing and calling animal sanctuaries in hopes of finding them a safe home. Meanwhile, the ducks flirted with adolescence, awkwardly sprouting snowy feathers. (Ping, the taller of the two, looked like he might take up smoking.)

After about a week and a half, I was losing hope. Then I received an email from a lovely woman who lives on a hobby farm in Port Perry. She was looking for more ducklings. She was vegan. She was perfect!

We chauffeured Ping and Gaston to their new home, and as we crunched over the gravel road, I felt as if we were slipping into the pages of a Beatrix Potter book. Bunnies hopped around sunlit grasses; a wooden swing hung from an old tree; miniature horses were enjoying a gambol about the pasture; and grown-up ducks promenaded about, their plumage white and plump as summer clouds. If the owner had offered to adopt me, too, I would have happily moved in. We left our ducks and headed home, feeling the sadness of empty nesters (forgive the pun).

The duck’s home farm never followed up with me or attempted to get them back. But a couple of months later, the adoptive parents got in touch to send me a photograph of Ping and Gaston. They were adults. In their snowy splendour, they were strolling about with six other ducks.

“They have a great duck life!” she wrote, “free to roam and be with their friends.” They somehow found what the pandemic has taken from us all—freedom and the comfort of community. I felt a certain swell of maternal pride, nostalgic for their golden babyhood and for the duck days of the pandemic summer. Finding them this country house of dreams was the best thing I did in 2020. Also, maybe the only thing.

These other pandemic pet adoption stories will warm your heart!

Our streaming services can feel like part of the family. Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime Video, and others offer up television shows to binge-watch when we feel like staying in and movies when we need an adventure, a laugh, or a little romance. When one of our streaming services is hacked, it can almost feel like a violation of our home. The hacker has access to our favourites list and can add and subtract their own picks, as well as watch our account without paying. Even worse, they can steal personal information from our profile.

So, how can you tell if someone has unauthorized access to your streaming services? Here’s how to find out for sure—and what to do about it.

Strange shows are popping up

Checking for unusual shows is one of the easiest ways to tell if your streaming account has been hacked, according to Fausto Oliveira, principal security architect at Acceptto. Most streaming services have a “continue watching” or “recently watched” list. If you see shows in one of these lists that you haven’t watched, this is a sign that someone else has access to your account. Share an account? Ask your friends or family if they possibly watched those shows. If not, your account may be compromised. (Change your settings immediately if you use any of these weak passwords.)

There has been an unusual log-in attempt

If you’re still unsure as to whether your account has been hacked, check Recent Logins, Recent Device Streaming Activity, or the Manage Your Devices section of your account. Here, you will find a list of all of the devices that have logged into your account. Look for anything strange that may be a clue. For example, maybe you only use Apple products and you see a sign-in from an Android device, or you only use your television to stream shows and you see that an Xbox has signed into your account. A suspicious device is a good indication that a stranger is using your account.

If everything looks fine, be sure to take a look at the location of the devices in the list. You may see an address that is clearly not yours. This is another red flag.

Your account has been upgraded

Do you suddenly have add-on channels or was a movie you’ve never heard of rented on your Prime Video account? A stranger has probably been making some upgrades on your account to get maximum enjoyment—while using your wallet. (Find out 18 secrets of people who never get hacked.)

What to do if you suspect your account has been hacked

If you think your account has been compromised, change your password immediately, and when the service asks if you want to log out on all devices, do it. This will sever the connection the hacker has with your account.

Next, check to see if there were any charges to your account that you didn’t make, like additional services added or unwanted movies ordered. If you find some unusual charges, contact the streaming service’s customer service department to see if you can have the charges reversed.

Prevent your streaming account from being hacked again

There are some simple ways to better secure your streaming services, and it starts with better password hygiene, according to Daniel Smith, head of security research at Radware, a cybersecurity company. Use complex passwords, and don’t reuse passwords across different accounts. These are just two of the password mistakes hackers hope you’ll make, and avoiding them can dramatically improve your security.

Also be careful when you travel. It’s become commonplace for hotels and other travel rentals to allow visitors to log in with their own streaming service. “Exercise caution when doing this and ensure that you properly log out of these services when checking out,” says Smith. “Leaving your streaming service logged into a shared device, like a rental’s TV, can lead to a compromised account.” (Find out 13 more ways hackers get you when you travel.)

Another good practice is to be very careful with emails. Tim Sadler, the CEO and cofounder of email security company Tessian, offers these tips:

-

Question the legitimacy of any emails that come from streaming services, and if the email is asking for “urgent action,” verify the request by contacting the company directly.

-

A particular phishing scam reels people in with a billing-error email, so check your bank statements to see whether you have actually paid your monthly fee for your streaming service.

-

Scrutinize landing pages that links in emails take you to—before entering payment or account information. For example, does the URL match the legitimate brand’s URL, and can you see the padlock on the web address bar? If so, the site is probably legit.

Next, find out the scary things hackers can do when they have your email address.

In May 2013, my father earned his first full year of sobriety in over a decade. To celebrate, he drank again.

I knew this because I had been trying to call him and couldn’t get through. He lived alone in Halifax and normally couldn’t go more than a few hours without calling me to speak of something inconsequential. So when he didn’t answer the phone, I knew. My father was a 68-year-old, thrice-divorced ex-chemist with a penchant for rousing the spirits of everyone around. There was only one thing that could suppress his vitality: himself, drunk.

As in the past, after a few days of not being able to reach him, I got the hint and stopped trying. I was 24 by that point. I had learned not to engage with him when he was drinking, for both our sakes. My steady closeness to his tumultuous recovery during my early adolescence and teenage years gave me an aversion to his relapses as an adult. Anything I ever said when I was upset only added to his list of personal wrongs that made drinking seem right. I’d keep my distance, and he’d keep his drink.

That May, my middling garage-rock band was readying itself for a long tour through Canada and the United States. After a week of zero contact with my father—his binges were lengthy—I looked at my phone during a practice session and saw a series of missed calls from him. Worried, I called him back, and he answered immediately. His voice was shaky and had its often-buried Northern Irish accent, as it always did when he’d been drinking. Over the course of a strained conversation, he confessed that he needed my help. “I’m done now,” he said.

I knew what he was facing. Now that the journey into the depths of his sadness was complete, he had to begin the slow, painful crawl back to sobriety. Within a day, the withdrawal symptoms would kick in. At first, those would be tremors, anxiety, nausea and restlessness. But soon he could experience seizures, dehydration—and possibly even delirium tremens (DTs), which can cause fever and hallucinations.

When he reached this stage, it was crucial that he be admitted to a public detox facility—seizures and DTs coupled with any of the other symptoms can be fatal. In fact, the mortality rate among those who experience this type of withdrawal is five to 25 per cent. Contrary to popular belief, withdrawal symptoms for those addicted to alcohol can be much more severe than those from other drugs—even drugs that are more commonly vilified by society, like heroin or oxycodone. Patients in detox from alcohol need to be closely monitored by medical personnel and, in some cases, may be given medications, often ones from the benzodiazepine family.

Given my father’s age, he was at risk for cardiovascular complications. Many times in the past, his heart had stopped beating, though thankfully only when he was already under medical supervision. This time, however, when my dad called Dartmouth General Hospital, they told him there wasn’t a bed available. He was to call back the next day, and then each day after that, to check again. After a few days of calling the detox facility without any luck, he finally called me.

My dad wasn’t alone in his desperation. According to a count in 2016, Halifax, with its population of over 400,000, only had 16 publicly funded detox beds for adults. With that capacity, some people were waiting anywhere from several days to three to four weeks to receive a bed and treatment. Chris Parsons, the provincial coordinator for the Nova Scotia Health Coalition—a non-partisan public health advocacy group—calls this “woefully inadequate.” For many people trying to get sober, he says, “A five-day wait period is the difference between them deciding they want to turn their life around, or relapsing.”

Meanwhile, across Canada, there have been cuts to already scant public addiction treatment programs. In Montreal, for example, the city’s only free public detox and addiction treatment centre removed 10 of its 28 beds in 2018. And a year later in Ontario, citing a low success rate, the provincial government cut funding for Fresh Start, a program that helped low-income individuals struggling with addiction find employment.

In decisions about where to cut back on health care, Parsons says, certain services are privileged over others. “Things like addiction treatment, mental health treatment and ensuring that you have culturally competent care for immigrant communities are seen as extras,” he says.

Recently, of course, COVID-19 has made everyone more aware of the gaps in our public health system. As the virus spread through our cities and nursing homes, and as many of the most vulnerable have gotten sick and died, it’s become impossible to avoid acknowledging just how thinly our systems are spread after decades of ruthless government austerity.

For example, when it comes to hospital-bed shortages more generally, many Canadians would be surprised to learn that Canada does worse than most other developed countries. According to the World Health Organization, high-income countries have an average of around four to five beds per thousand people. To cite a few examples, Korea has 12.4 beds per thousand people, France has 5.9 and the United States has 2.9. Yet Canada only has 2.5 hospital beds per thousand people; we are consistently at or near the bottom of the list of comparably well-off countries.

In the absence of sufficient public services, family and friends overextend themselves to pick up the slack, playing the role of at-home caregiver out of a sense of obligation to those they love, thinking that if they don’t, no one else will. This may save taxpayers money, but there are untold costs to the people who volunteer, willingly or not, to fill the gaps that are left.

Since 2005, my dad had lived in a one-bedroom apartment within Joseph Howe Manor in Halifax’s south end, a subsidized-housing complex for senior citizens that cost residents a third of their monthly income, whatever that might be, each month. As a kid, I stayed with him during summers, holidays and weekends, sleeping on his fold-out couch in the living room. Most of that time, though, I opted to crash with friends so as to avoid him while he binged.

When I walked in the day he called for help, his television was set to a low, companionable volume in the living room, and he was curled up in his bedroom on a lumpy, sweat-soiled twin mattress with a single sheet over his body. He tried to get out of bed, but he was too weak. I gave him a protein shake, which he’d requested, and put two more cases of it in his refrigerator.

Being helpful to my dad in this way wasn’t always my approach. As a teen, after years of having to keep his recovery attempts a secret from everyone, including my mother—and so not being able to get any support from others—I became resentful of that burden. I cursed his name at any instance of a relapse and would abandon him for days on end. He’d sit alone, sorry and ashamed, until he finally felt strong enough to call on an old friend for help.

My distancing tact—called “tough love,” both colloquially and officially in the field of addiction—is practised by many, even if they don’t know its origins. The concept was first touted in Al-Anon, the support group for loved ones of alcoholics founded in 1951 by Lois Wilson, the wife of the man who co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous. Then, in 1982, Phyllis York, a family therapist, brought it to the masses in her bestselling book Toughlove, which urged readers not to bail out their children if they were arrested, and to cut off contact if they relapsed.

Never officially schooled in the ways of tough love, I came to it naturally, thinking that denying him compassion might be a form of punishment he would learn from. Or other times, I felt I had earned the right to express the anger I’d long withheld, regardless of how it made him feel. But in the end, none of it made me feel better and none of it helped him. Instead, when I withheld my love and compassion, he had little reason to hold back on drinking himself into further oblivion.

After entering my 20s and gaining distance from my dad’s drinking, I began to understand that it wasn’t necessary for me to reprimand him when he drank. I could just be there for him, or check in on him, without scolding him and exacerbating his feelings of failure and worthlessness that accompanied his binges. In other words, I could care without putting myself in harm’s way.

Surveying my dad’s apartment that day in 2013, I saw empty beer cans strewn throughout the living room, as well as several empty bottles of Listerine, which he’d turn to when he was out of alcohol. I wanted him to know that I wasn’t there to make him feel bad about another failed recovery, so I cleaned his apartment as best as I could. My standards for cleanliness back then didn’t go much higher than his, but I’m sure he saw me, out of the corner of his eye, sweeping dust and bottle caps into a chip bag, and felt my love for him. After chatting with him for a bit, I went back to my friend’s recording studio to get ready for the tour, which was less than a week away.

The next day, my dad called again. With an even shakier voice, he asked if I could go to a pharmacy and buy him Gravol, which helped curb his nausea, vomiting and motion sickness. When I arrived with it, he was on the couch, facing the back cushion, as though he were giving his television set the silent treatment. He immediately took three of the pills with a glass of water. “Hope I don’t just throw these up,” he said. I hoped so, too.

As the days passed, I became increasingly worried that a bed in detox wouldn’t become available before something terrible happened. I worried that he was having seizures when I wasn’t there. I worried his heart might stop. I worried I would be out of town when he died.

My lack of expertise in treating a substance-use disorder wasn’t the only reason it was a bad idea for me to help my father with his recovery. He wrestled with the guilt and shame of being nursed through withdrawals by me, his son, as I had to also play the role of therapist to him—a situation that only exacerbated the depressive thought patterns precipitating his relapses.

When a dearth of government support thrusts the onus of around-the-clock care onto someone’s family and community, we would like to think that those people respond with finesse. But they’d need resources for that, such as outpatient treatment programs, safe-injection sites, cognitive behavioural therapy or medications that diminish cravings, like naltrexone.

Of course, some families can afford to send their loved ones to for-profit facilities, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars. But also, I’ve seen and heard many stories about low-income individuals finding ways to pay the exorbitant treatment costs, either by selling belongings, taking out mortgages, liquidating their savings or sinking into unfathomable debt. Families in this situation can create the sort of environment that makes it even more difficult to thrive in the future.

“Say you get out of rehab and it turns out your brother sold his truck to pay for your treatment,” Chris Parsons says. “That guilt weighs on you and impacts your ability to maintain your sobriety.”

In situations like mine, where a private centre was out of the question, a person shouldn’t be forced to choose whether they look out for themselves or help a family member through detox. No untrained and heartbroken family member should be left to carry that weight when they lack the resources they’d need to do it properly.

To my relief, on the morning I left for New York, the first stop on my band’s tour, my dad finally received word that there was a bed for him in the detox ward. In total, he had waited five days, longer than most waits he’d ever had to endure. By that point, he’d already passed through much of the disease’s long night, as I thought of it, but the hospital saw to it that he received the care needed to get through the rest.

After seven days in detox, he returned home. I was on the road, but he told me over the phone that he’d never felt as cared for during a withdrawal as he had in the week before finally getting that bed. I’d only provided him with the most basic comforts—food, conversation and constant check-ins—but he said it was more than he had received in years. He told me that when he entered detox, it was with less dreariness than ever before because I’d made him feel that his worth wasn’t based on his sobriety.

Like most stories of recovery, it didn’t end there. Even after the relapse in question, my father relapsed twice more before he passed away from a brain tumour in 2017. Through all that, I came to understand that this back and forth was just the rhythm of his condition.

I feel lucky that I didn’t make a rash decision to cut my dad out of my life for good, and that I came around to treating him with the love and compassion he deserved, sober or not. As imperfect as they were, I wouldn’t have wanted to miss out on the last few years I had left to share with him.

Next, find out what one mother learned after her daughter came out as trans.

© 2020, Maisonneuve. From “Labour of Love,” By Ryan David Allen, Maisonneuve (August 25, 2020). maisonneuve.org

Red Flags Someone Is Stealing Your Wi-Fi" width="295" height="295" />

Red Flags Someone Is Stealing Your Wi-Fi" width="295" height="295" />