Casino Royale was the first book I ever read, from front to back, all in one sitting.

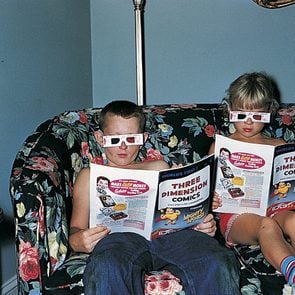

I read a lot as a kid. Everything in sight. I wasn’t overly picky, as there just had to be words on a page. When we were younger, my parents drove my older sister, my younger brother, and me to the library, so we had a pretty good selection of books to choose from.

I read comic books, such as Batman, Superman and Archie, and actually bought used copies at rummage sales. I read the cereal boxes as I ate my corn flakes. There was always a contest or mail-in offer on the package. We would cut the tops off of the cereal boxes for proof of purchase and my mother would tape four quarters on a piece of paper. We then dropped the envelope into a mailbox and would receive a cheap game or toy for us three kids to fight over a few weeks later. It was never as big in real life as it looked on the pacakge. Times have changed now, however, and the only form of text on today’s cereal boxes are the ingredients, and the only one I pay attention to is the fibre.

For roughly three years of my life, from 11 to 14 years old, I would read the newspaper as I trudged from door-to-door on my paper route. I remember dodging hydro poles and fire hydrants without looking where I was going, keeping up on politics, news and sports. I read pretty much everything but my school textbooks.

Bedtime was for pleasure reading. I went through a James Bond phase. They were pretty easy reads (about 200 pages) and much better than the movies, which have always been a letdown for me. But I had never read a book completely through in one night before.

It was band practice night at the Salvation Army, during the winter of 1965, and they were located next door to my parents’ house. They would go on for hours and break up at around 10 o’clock. Like living next to a set of railway tracks, or an airport, I got used to it, and I remember that night vividly. They were on their third run through of a rousing rendition of “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus” and getting lost in a delicious spy thriller was a great way to shut out the booming bass drum from the Sally Ann.

I hunkered down in my homemade sheets. My mom had sewn together cotton sugar sacks for our bedding and mine still had a big faded Lantic sugar logo on the bottom left panel. My pile of thin blankets kept me warm not by their thickness but by their sheer numbers. I adjusted my Toronto Maple Leafs lamp and settled in for a good old session with James.

James Bond: A Man Like None Other

The Bond books provided great escapism, as he shot and gambled his way around the world. He went to the casinos in the south of France. He skied in Europe. He went scuba diving in the Bahamas. He chased criminals in Russia. Women quivered and men shivered at a steely look from his cold, assassin-like eyes. He drove an Aston Martin, a car we didn’t even see on the streets of Toronto. He used the lethal combination of a Walther PPK pistol and his brain as primary weapons. He slept on silk sheets, not sugar sacks.

Comparing this character’s lifestyle to the working-class neighbourhood of west-end Toronto that I called home was something I could only dream about.

His fight was always with good and evil and there was almost always a good-looking femme fatale in the dark corner, and an equally beautiful friendly agent covering his back. By the end of the book, James had usually made love to them both.

I started reading about nine-ish and, when I reached the halfway point, just like James at the gambling tables, I decided to go “all in” and finish the book. It was a school night and I probably would have gotten in trouble if my parents had checked on me, but they didn’t, and sometime after midnight, I polished off the book.

Unlike James, I don’t like vodka martinis, shaken or stirred. He taught me that class is not something you attend from 9 a.m.-3:30 p.m. on a school day. I have never needed a tuxedo, but I did learn that European and Caribbean casinos are much more sophisticated because of their elegant dress codes, than the T-shirt and shorts crowd of North American casinos. I even lugged a jacket, tie and dress pants with me through Europe, on my honeymoon during the summer of 1981, in the hopes that we would go to a casino in the south of France. We did.

I think, most of all, Mr. Bond instilled in me a desire to see and experience these exotic places. Places that were so completely out of reach for a kid like me. Travel seemed unattainable and I could live vicariously through James. He helped me want to experience something different and unusual, and for that, I thank James.

Next, check out another Bond aficionado’s ranking of all the James Bond books—from worst to best.

Hello Meryl. This is my best 60th birthday present. Long time no see. xx Cathrin

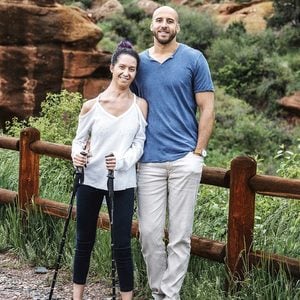

I tapped my note to Meryl the same night she sent me a birthday text. It was our first communication, I should mention, in 20 years. We’d met as schoolgirls when we were six and were each other’s first friend. It wasn’t that we’d meant to drift apart—it was just life, really—but after so many years the silence between us had become too deep to breach. This birthday text was momentous, in other words. Let’s call it Stage One of the reunification.

The temperature outside my Toronto house had nosedived to -18 C. It was the kind of night when Meryl and I, at 12 or 13, might have gone out for an epic winter adventure, leaping over the ice hills that rimmed the shore of Lake Ontario. Newly 60, that sounded like at least one broken hip. Meryl wrote back within minutes, and we were off.

I thought about the first time I saw Meryl across a paved schoolyard in Grimsby, Ont., our hometown. (I’ve changed Meryl’s name, at her request, for this story.) She was dark-eyed and watchful, like me, and it was like recognizing something important in myself. Meryl, in her first text back, suggested we meet in the real world, but that felt a bit hasty. Sometimes I didn’t think about Meryl at all, sometimes I thought about her a lot, but the one constant was that she was safely situated in the past. This one-text-away Meryl was very present, and I proceeded with caution.

As we texted back and forth over the next few days, Meryl was the first to relax into randomness, describing a bird or tree outside the window of her home, or remembering some old boyfriend or other. We lingered on the soft pillow of nostalgia but didn’t smother ourselves with it.

The memory-syncing part was cool and mysterious. When Meryl mentioned the Tea Room on top of the Grimsby escarpment, a rickety stick building suddenly appeared in my mind. It was made of logs, wrote Meryl, and the Tea Room stopped wobbling. Giving it shape together made our memories, if not free of falsehood—we both tilted toward the positive—then at least real. The magnificent magnolia tree at Livingston and Main needed no prompting: Big! Bold! Pink! But more satisfying than putting Grimsby back together again was that Meryl’s memories made my version of things less dubious. It had been a long time, if ever, since I’d felt that I was a reliable keeper of the past.

We caught up on our adult lives, too, as we texted back and forth. She still worked as a florist, as she had when we’d last spoken. And she’d stayed in the same Ontario town she’d moved to when she married, and raised her three daughters there. Still in the same house, it is now yellow.

Our moms were a steady topic. They were both 91 and both living. Or, to put it another way, they were both 91 and both dying. My mom had just lost the part of her mind that would have remembered our childhood, while Vivian was in her right mind but couldn’t talk properly after a recent stroke affected her speech. Our mothers’ connection to each other, separate from Meryl and me, was mostly invisible to us growing up, but it was a subterranean current in our lives. Meryl was the first person I texted when my mom collapsed, and after she died, I remembered that I hadn’t asked about Meryl’s father, Clayton, a handsome, broad-shouldered man with a head of thick black hair. Clay died 12 years ago, wrote Meryl.

On March 15 at 7 p.m., 11 days after Mom’s funeral, Meryl and I had the Phone Call. Our first phone call, I’ll mention again, in 20 years. I was nervous enough to think of texting that I was sick, or tired, or sad—at least two of which were true. I called Meryl from under my covers, and she answered from under her covers, and we picked up where we’d left off. Neither of us finished our sentences, instead letting our thoughts dangle dementedly. “I just think…Here’s what I’d say about that…My strong feeling there is…” Our conversation would have been mind-numbingly inane to anyone else, but we understood each other. We’d grown up in the same place, we saw things the same way, we didn’t need to explain ourselves.

That Meryl and I were moving irrevocably toward the Meeting filled me with unease. We chose the weekend of April 25, when she was to arrive by train at Union Station early on a Friday evening. There were at least 15 texts about the time of this arrival—Meryl, I woke up thinking you should get the train that gets you in at 5 on Friday…Is it a GO train or a real train?—which was when I realized how old we’d become. Of course, I lost her at Union Station. Where are you?!?…I am here!!…Where is here?? Cue 15 more texts until I saw Meryl across the chaos of the station’s endless renovation. Her head leaned left like the first time I saw her. We laughed as we hugged and mostly stared at each other on the subway until we got to my house.

After a night in Toronto, our plan was to return to our childhood hometown. The next morning, we took the bus to Grimsby, about two hours away. The sun was high and bright but gave no heat. We walked past the giant pink magnolia tree, now severely pruned, and bought flowers to put on Meryl’s father’s grave, which was on the escarpment. We walked the path to the top, and just as we called out our houses—“there, there”—like we did when we were kids, two red-tailed hawks circled overhead, their tails turning golden in the sunshine. They cocked their heads to look at us, as if we were the unexpected ones. Meryl took the hawks as a sign, I wasn’t sure of what.

We made our way to Clay’s grave, where we put our flowers on the stone Vivian had designed; it would soon be hers as well. Meryl lingered under the struggling sun, and I stayed a little ways back until she was ready to leave.

Back in Toronto that evening, we had dinner at a midtown bistro, and finally got to the hard conversation, about the night when Meryl tried to kill herself. “I can’t believe Vivian is 91,” I said. I’d asked for seats at the bar because I thought it would be more intimate to be side by side, but I saw my mistake right away. To Meryl, with people on either side and a bartender hustling in front, the bar felt like a decision against intimacy. “I think of Vivian as more my own age,” I said. “Of course that’s not right, but you know what I mean.”

“I can’t wait to tell her you said that. She liked being one of us.”

I poked at my arugula salad. “I’m sorry I didn’t know Clay died, Meryl.”

I wiped the smudge of lipstick off my wine glass with my napkin and wondered not for the first time how people didn’t leave crumbs or smudges, a talent I couldn’t master. Meryl’s place and glass were both pristine, like her memory. Even when I thought I knew something, like the right direction to take in traffic (so, so rare) or the turn of a story from the past, I mostly kept it to myself. There were other ways to get at the truth. Also, I didn’t care about being right the way some people did, that was the simple fact.

“When I saw the hawks today, I kind of thought it was your mom and my dad, protecting us.”

“I love that,” I said, but really I was having a hard time concentrating. It hadn’t been a plan, exactly, to talk about that long-ago night, but after 24 hours of conversation, it had begun to seem pathologically evasive not to. Forty-five years had passed, enough time perhaps to finally broach the subject.

“So I guess there are a couple of things we haven’t talked about this weekend. Like that night?”

Meryl didn’t change the subject so much as make her way toward it, ahead of us in the distance. “Remember the time we climbed the mountain by the creek bed? We would have been 12 or so. I remember that.”

“I think so.” I saw the faintest sparkle of a creek as I dabbed my finger at a lingering crumb. “We don’t have to talk about that night.”

Talking about difficult things was not who we were, Meryl and me. Not talking was what bound us, even. How could I have forgotten that? I racked my brain for a new subject.

Meryl looked at me calmly. I was beginning to suspect that I was the panicker, not she. “No, I want to,” she said after a while. “I mean, I never have, but I want to now.”

We both paused then, and I thought about the part of the story I knew. It would have been a couple of years after the creek-bed climb. Meryl was 14, and she took enough pills to die. Vivian rushed her to the hospital, barely in time to save her life.

“Things weren’t great at home in that time, you’ll recall,” Meryl said finally. She looked me straight in the face and waited. “Yeah,” I said, although I didn’t really recall, or perhaps only faintly. We’d finally acknowledged the thing we’d never discussed. We’d said out loud that it had happened, and that was enough. That was plenty.

“You weren’t depressed or anything,” I said.

Meryl kept looking at me, until she seemed to make a decision to leave it there. “I often think if my mom hadn’t come to my room and asked me if I wanted pizza, I’d be dead now. I often wonder about that.” She looked down at her lap, then up again at me. “And your mother was very kind in that time. She tried to help me, after. She took me to see a priest and told me I could talk to her anytime.”

“I remember being mortified that she took you to a priest, of all things.” I rolled my eyes, which made me wobble slightly on my bar stool.

“I think maybe I’m more religious than you are now.” Meryl let me absorb this new idea of her before she continued her story. “Your mom taking me to a priest was an act of concern. There wasn’t therapy or anything remotely like that. It was a private, shameful event. Even now, it’s a shameful event. No one, not even you and me, Cathrin—we never talked about it.” It wasn’t exactly an accusation.

I skated over the fact that it had taken me almost five decades to mention that night and instead went back to what I knew: that Meryl had called me and told me she’d taken pills from the medicine cabinet. I thought she was trying to get high, our steady preoccupation once we became teenagers, and asked her if it felt good. She said it did, but also that she felt kind of funny. “Cool,” I’d said, and went back to watching Star Trek or whatever was on TV. But as we talked on our shaky bar stools, what happened after that call took on more shape.

“I’m pretty sure my mom told your mom, and that’s why Vivian went into your room.” My words seemed to ring out, although I was speaking quietly.

“No, that’s not how it happened,” Meryl said, and I might have left it there because she’d been right about everything else. “It was dinnertime. My mom thought I was hungry.” Meryl smoothed her napkin on her lap and spoke again without looking up. “How would your mom even have known?”

My heart was pounding. I was getting in the way of how Meryl remembered that night, but my words were too fast for me. “She knew because when I hung up the phone, I told her,” I said, and I knew that it was true. Even though, at 15, I’d made hiding things from Mom a defining purpose of my teenage life, I must have understood that Meryl’s life, and in a way mine too, depended on my telling Mom, because what might life have been if my best friend had died that night—on my watch? Not great, was my guess. Now, sitting side by side with Meryl, I wasn’t only sure that my memory of that night was accurate, I cared that it was.

“If that’s true, then it was your mother who saved my life,” Meryl said. She looked directly at me. “If that’s true, then it was you who saved my life.”

“Well, you called me, so I guess you saved your own life.”

We both took time to settle after that. I became so lost in my thoughts that when I looked at Meryl again, I was surprised to see her still sitting beside me. She looked like she’d wandered a long way too.

“It wasn’t a condition, you know,” she said. “It was an episode. That’s how I think of it.”

“Yes, I get that.”

“I don’t talk about it because I don’t want to be defined by it. I’m not defined by it.”

“I think that’s true,” I said. “It was an incident, not a lifelong affliction.” Incident, episode, that night, that time, before, after—we were careful with our words. The other words felt too violent, and further from the truth.

“I’m proud of myself, how I rallied,” Meryl said. It was a statement, for both of us. “It took longer than people realized.” All weekend I’d been carrying around the idea that I needed to take care of Meryl, and in that moment, I let it go. She didn’t need looking after by anyone.

Back at my house, we put on our mothers’ pyjamas, as we’d agreed we would. We were both wearing our mothers’ clothes a lot at this point. I wore Mom’s red and black silk muumuu with its massive flapping arms. This muumuu had been her sister Mary’s, and Mom never washed it because it smelled of Mary and now I didn’t wash it because it smelled of Mom. That’s 30 years of smell on one muumuu. Meryl came out of my spare bedroom in her mother’s leopard-print silk pyjamas.

“Very Vivian,” I said.

“Very Vivian,” she said. Meryl liked to repeat my words; it was her empathy.

The next day, she left Toronto with a simple, factual question she could take to her mother about the sequence of events that night. They hadn’t talked about it either, so it wasn’t a small thing when Meryl sat with Vivian and asked her, “Mom, did you come to my room that night because Mrs. Bradbury had called you?” And my mom locked eyes with me, her eyes wide and so much pain in them, and she didn’t have the words, but she nodded yes. Meryl wrote this to me right away. To have this talk finally when she could no longer talk. It was strange, Cathrin. It was sad. It was huge.

I read the note from Meryl in my kitchen and started to cry, my tears plopping onto the round white table. It sounds dramatic to say that, because getting the details right about that long-past night was simple enough. Mom, Vivian and I would have done anything to save Meryl, so it didn’t matter who told whom. But knowing that it was all four of us, and that Vivian and Meryl had been able finally to nod that truth to each other? And knowing for sure that I hadn’t gone back to my Star Trek show. Beside the ordinariness was this hugeness, like Meryl said.

Six weeks after Meryl’s visit, Vivian died, and it was remarkable how that midtown bistro conversation happened when it did, exactly between the deaths of our mothers. It changed things for Meryl and me after that—if only we could have told our moms. Meryl would have asked Vivian to forgive her and told her how glad she was to have lived that night. And I’d have told Mom that I finally understood she had been my ally in important and even life-saving ways. My idea of her changed, but not only that, a new idea of myself began to take hold, a more reliable, less rickety one, like the Tea Room on the escarpment. I noticed something begin to grow in myself. A voice, maybe.

Excerpted from The Bright Side, by Cathrin Bradbury. Copyright © 2021, Cathrin Bradbury. Published by Viking Canada, an imprint of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

I used to think that the best drive in our great country was from Calgary to Jasper by way of the Icefields Parkway, but I am going to let you in on a secret: the west coast of Newfoundland is every bit as amazing. I know many people who have travelled to the eastern part of the province and have raved about it, but the west coast is rugged, full of small fishing communities and some of the nicest people you will ever meet.

Being from Toronto, we don’t have the type of rugged landscapes nearby that offer a glimpse of what Eastern Canada truly has to offer. You can imagine my surprise at the wondrous vistas before us the minute we got off the plane at Deer Lake. Our visit was to take us to Norris Point, then to Lobster Cove, Gros Morne, St. Anthony and then back to Port aux Choix and finally to Lark Cove, west of Corner Brook.

Our first stop in Norris Point was to give us a home base to get to Gros Morne, but one of the wonderful people we met gave us the opportunity to climb one of the mountainous hills close to our accommodations. It took a while, but the struggle was worth it when we saw the view from over 600 metres above Neddy Harbour. After an hour of taking some great landscape shots, it was time to call it a day with a sunrise call at 3 a.m. to get the view of Neddy Harbour from Main Street.

It was like the sun never really went down, when the rooster crowed to get us up and at ’em. With a hot coffee in hand, off we went to the harbour and what we saw made our eyes as wide as saucers. The sun was starting to rise but was still behind the hills, and a slight layer of cloud was just hanging above the water. We set up our tripods and began clicking away, capturing some quality photos that I have been challenged to get since.

A couple of hours later, it was time to travel to Gros Morne. This natural beauty, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was high on our list. Spectacular in its beauty, you are dwarfed by the size of the valley of cliffs that the tour boat passes. Ninety minutes later, as we departed the boat, we could not stop talking about what we had witnessed. Waterfalls and cliffs that match the fjords in Norway were a surprise for us and occupied our conversation as we travelled to Lobster Cove for lunch.

We really did not know what to expect at Lobster Cove, but we’d heard back home that we needed to stop by there to experience the vistas. The century-old lighthouse once served as a beacon to safely guide fishermen and sailing vessels into Bonne Bay. It did not disappoint as a terrific focal point for our afternoon shoot.

One thing that became clear was the slowed down pace of life that we were starting to adapt to. Back home it was always go, go, go and here it is slow, slow, slow. It was now time to return to our home base in Norris Point and get a good night’s sleep before our trip to St. Anthony to hopefully get a shot of an iceberg.

It was a mere four-hour drive up the western coast of Newfoundland to get to St. Anthony, which is close to the northernmost point of Newfoundland and the gateway to Labrador. It was wonderful. We spent the rest of the day climbing the more than 400-steps on Dare Devil Trail to get a great shot of St. Anthony from above. It hit us that we were so far north when we realized it was still light out at 11 p.m. There must be big sales on blackout curtains for people who live here!

We had an 8 a.m. scheduled tour time to go out and spot icebergs in St. Anthony. We boarded the boat in the harbour and took some seats at the front of the boat for the best view. Fun fact: the waves get really high once you get out to the ocean, which had us running to the safety of the inner, closed-in viewing area.

Thirty minutes later there it was, about nine metres high, the ice beneath the surface of the water glowing with an aqua colour I have not seen before. Circling the mammoth piece of ice, likely thousands of years old, was a stunning sight. To add to the experience, the captain had a sense of humour—playing the theme song from the movie Titanic while we toured around.

Next was a three-hour drive to Port aux Choix, where the Point Riche Lighthouse is located; we were hoping to see what life is like in this working fishing town. The owners of the B&B we stayed at were so wonderful, as it seems all Newfoundlanders are! They told us if we asked one of the lobster fishermen in the bay, they would take us out while they checked their traps. So, ask we did and at that point we gained a whole new respect for these men and women. The work is hard, and the water is rough and yet these wonderful people go out every day. We spent the rest of the day at the lighthouse and even caught sight of a minke whale following a fishing boat for the spoils of the catch.

Now we were on to the final two days of our trip. We’d booked a great cabin just outside of Corner Brook close to Lark Harbour. As we spent the night enjoying the deck and the view of the water, we saw three or four bald eagles soaring around us. Although they were too far away to snap a good photo, it was enough just to enjoy their company.

Our final stop before we made our way home was to Bottle Cove. Its turquoise waters and jagged cliffs made this our favourite stop of the trip. It was too bad we did not have an extra day to spend there as it provided the best photo opportunities of all the beautiful locations we visited.

It was time to say goodbye to this bucket-list trip. If you’re ever in the region, make time to see the west coast of Newfoundland—you won’t regret it.

Check out more essential experiences in Atlantic Canada.

Say hello to the coolest treat around. Sweet and creamy ice cream is beloved by all ages—and there’s no shortage of ways to enjoy it. Read on to learn everything (yes, everything!) you need to know about ice cream; including recipes, products and tips for mastering it at home.

How to Make Ice Cream: Methods

Making homemade ice cream is not as complicated as it sounds. And, while you definitely can invest in gear and gadgets to streamline the process, it’s not necessary. We’ll show you how to make ice cream a myriad of ways—you just pick the one that works best for your family.

How to Make Ice Cream without an Ice Cream Maker

To make ice cream without an ice cream maker, you’ll need a handful of common kitchen tools, including a mixing bowl, 13 x 9 pan and a spatula. Time and patience are other key ingredients, since this method relies on a slow, meticulous churning process.

How to Make Ice Cream with an Ice Cream Maker

If you plan on making a lot of frozen treats, it’s worth it to invest in an ice cream maker. These sleek machines yield professional-quality results and less hands-on time. You’ll still need to prep your ice cream base and, in some machines, the maker’s canister before reaching for the scoop. (Impress any guests with this coconut-lemon ice cream cake.)

How to Make Ice Cream in a Bag

Do memories of summer camp come flooding back at the mere mention of making ice cream in a bag? You’re not alone. This kid-friendly, hands-on approach uses salt and muscle power to create silky smooth ice cream.

How to Make Ice Cream in a Coffee Can

Similar to the bagged method, coffee can ice cream relies on rock salt and movement to yield a frozen treat. Except instead of mixing with your hands, you can roll or even (gently!) kick the can around. This method is great if you want to get a little exercise in before indulging! (Check out more clever coffee can hacks.)

Tips for Making Homemade Ice Cream

Just like any skill, practice makes perfect. But we have a few ice cream-making tips to get you started, including:

- Reach for quality ingredients: A basic ice cream base has very few ingredients, so make sure you’re including top-notch items, like fresh cream and pure vanilla extract. Trust us—you’ll be able to taste the difference!

- Ward off ice crystals: One of the biggest challenges you’ll face when making homemade ice cream is ice crystal formation. These mini ice pieces can ruin the texture of your ice cream and affect the flavour. Keep them at bay by sticking to your recipe’s sweetener amounts and taking steps to store the ice cream in an airtight container.

- Experiment with flavours: Feel free to go wild with your ice cream flavour choices. You might just create a new favourite! (You’ll love this cherry and chocolate ice cream pie.)

Ice Cream-Based Desserts

A scoop tastes delicious on its own (or packed into a cone), but you can also use ice cream to make next-level desserts.

Milkshakes

The 1950s called—and they said this sweet sipper is never going out of style. A classic milkshake blends milk, ice cream and your favourite mix-ins until smooth, then is topped with whipped cream. (Learn how to make the best milkshake ever!)

Sundaes and Splits

Another classic treat, ice cream sundaes are laden with sauces, fresh fruit, nuts and other tasty toppings. We love an old-fashioned banana split, as well as this decadent turtle sauce that blends smooth chocolate and sweet caramel. And, to make your sundae even sweeter, serve it in a homemade ice cream bowl.

Ice Cream Cakes

For a show-stopping dessert, you can’t go wrong with an ice cream cake. These novelties combine all of the good stuff—ice cream, cake, cookies, whipped cream, sprinkles and more—into an easy-to-slice dessert. (Try this nostalgic recipe for strawberry crunch ice cream cake.)

Next, check out this collection of 20+ refreshing ice pop recipes to make this summer.

The Okanagan Valley is known for its beautiful lakes and divers, rich landscapes with mountains, forests, rivers, wetlands and semi-arid desert. These landscapes, along with many protected wildlife preserves and four distinct seasons, make the Okanagan an exceptional place for year-round birding. The Okanagan is home to more than 300 bird species, including around 35 that are endangered or threatened.

There is quite a dynamic birding community in the Okanagan—from teens to seniors and all ages in between. I have had the privilege of meeting many, some of whom have become good friends. More experienced birders are happy to share their wealth of knowledge with others, including me, who are less experienced and still learning.

Photographing birds is a year-round activity, but many birders will tell you spring and summer are the best times in this area because there are so many species that come here to breed and raise their young. Although it is fascinating to watch the nesting habits and appearance of baby birds throughout spring and summer, fall and winter can also be quite active as many birds, some rare, migrate through the Okanagan. You can find many highly populated bird areas from Osoyoos in the south Okanagan to Salmon Arm in the north.

As I gained more experience and skills as a photographer, I discovered that my own backyard had an abundance of birds. I began feeding them during the fall and winter months when their food source was scarce, while photographing the many species that would come to the feeders. Now a rewarding passion, I explore various parks, trails and bird sanctuaries several times a week to view and photograph these beautiful subjects.

Ten years ago if anyone had told me I would be a birder and bird photographer, I would have laughed at the idea. As an outdoor enthusiast, birding fits in well with my lifestyle, and when I leave the house for a walk or an outing, I always carry my camera.

On any given day in the field, I might see tiny hummingbirds, great blue herons and trumpeter swans, as well as eagles, hawks, jays and many songbirds and woodpeckers. Some days though, there may not be much bird activity, but that’s all part of the adventure. I am in awe of the many species of birds that can be found right outside my door.

Some of my favourite birds to photograph around the Okanagan are lazuli buntings, bluebirds, owls, and cedar and bohemian waxwings. Before I ventured into birding, I had no idea the number of colourful birds we have in our area. There is the brilliant blue of bluebirds or lazuli buntings, the bright yellow and orange of the western tanager and the very colourful patchwork of the wood duck, just to name a few.

Last fall, I went on a birding adventure with a friend and an expert birder as a guide to try and spot a pygmy owl. The pygmy owl was high on my list of birds to photograph. I was so excited when one flew and perched right where we were patiently waiting. It sat still for several minutes looking for his prey while we quietly observed and photographed it.

Pygmy owls are only five to seven inches in height and one of the few owls that are active during the day as well as at dusk. They are often mobbed by smaller birds such as wrens, warblers, jays and blackbirds to distract and scare them off.

As a birder, it’s so rewarding to be able to come across a rare species that may only be passing through on their migration route. One rarity that stands out for me happened about three years ago when I was told about a long-tailed jaeger that was spotted at a local park in Kelowna. This seabird breeds on the Arctic tundra while spending the rest of the year at sea, so it was highly unusual that one was here by a freshwater lake. When a birder spots and positively identifies a bird for the very first time, we call it a “lifer” and this was one of my first.

While sipping coffee one November morning, I watched about 30 California quail scratching in the leaves and soil to find seeds dropped by the songbirds from the feeders above. These quail have a comma–shaped topknot of feathers leaning forward from their forehead. They remain here year-round and will often have ten to 16 young. Quail families gather their young together with other families for protection, where they find safety in numbers. A flock of quail is called a covey.

While observing birds in their natural habitat, it is our responsibility to follow ethics and rules, such as keeping our impact on sensitive or protected areas to a minimum. For instance, it’s important when coming across a threatened or endangered species, or an active nest, to keep the location private to avoid stressing or further endangering the birds.

Birding and bird photography makes you more aware of the environment and more appreciative of our beautiful surroundings here in the Okanagan Valley.

If you enjoyed this guide to Okanagan birds, you’ll definitely want to check out this gorgeous gallery devoted to the birds of Canada.

Before the incident—before his body became a battleground for competing poisons and his story the subject of zoological curiosity—Jeremy Sutcliffe had actually liked snakes. He’d found them beautiful, even.

Besides, the tattooed 40-year-old wasn’t someone who shied away from wild creatures. He was an avid outdoorsman who took every chance he could to camp and fish. That love of nature had been part of the reason Sutcliffe and his wife Jennifer, 43, had recently moved to South Texas from Kansas. The place they’d bought on Lake Corpus Christi, a short drive from the Gulf of Mexico, was their dream home. Or that’s what it was going to be. At the moment, they were living in a trailer on their one-acre lot, and the house was still a fixer-upper. A “total gut job,” Sutcliffe called it, with the pride of someone who plans on doing the gutting himself.

On a steamy Sunday morning in May 2018, the couple was tidying their yard in preparation for an evening cookout with their daughter and her two young children. At around 10:30 a.m., Sutcliffe began mowing the lawn while Jennifer worked on the garden. She had just reached down to grab a weed when she saw it: a western diamondback rattlesnake, right next to her hand.

Jennifer leaped up as the snake, a metre long, rose into a striking position, with its dusty triangular head tensed and its tail rattling. “Snake!” yelled Jennifer as she backed away. “Snake!”

The Deadly Blow

When Sutcliffe heard his wife’s cry, he figured she’d run into one of the harmless rat snakes that often showed up on the property. He grabbed a shovel to shoo the creature away and jogged around the house to the garden. That’s when he heard the rattling. His wife was cornered between some shrubbery and the wall of the house, a viper directly in her path.

He first tried to scoop up the snake using the shovel, without success. Then he did what was necessary: he raised the garden tool and brought the edge down hard through the snake’s body just below the head, decapitating the reptile.

Jennifer went into the house, her heart hammering, while Jeremy headed back to the garden. About 10 minutes later, when Jennifer said she was going to let their two small dogs out, he decided to move the dead reptile. He looked at the creature lying limp on the ground. Its head rested on a paving stone, attached to a stub of body.

He bent down to pick up a stick lying next to the snake’s head so that he could flick it away. But before his hand even touched the ground, the snake attacked—a blur of motion as the creature launched itself forward. Burying its fangs into Sutcliffe’s right hand down to the bone, the snake injected venom that immediately made his hand feel like it had been smashed by a massive weight. “It bit me!” he yelled in horror.

For Sutcliffe, it was like something out a zombie movie—an undead creature’s final act of revenge. But the truth is, bites from decapitated snakes aren’t uncommon. “Reptiles can stay alive for quite a long time after sustaining a life-limiting injury,” says Christine Rutter, a veterinary critical-care specialist at Texas A&M University who has seen her share of snakebites. A decapitated snake is like a chicken with its head cut off, only with a much longer survival time because it’s a cold-blooded reptile with a slow metabolism.

In that moment, however, all Sutcliffe was thinking about was that the snake that he’d killed was now trying to kill him. The creature’s jaws were clamped around his hand. Desperate to free himself, Sutcliffe inserted the fingers of his left hand beneath the snake’s upper jaw and tried to pry the fangs free. He managed to remove one of the fangs from his middle finger, but as he tried to pull the head loose, the viper’s jaw clenched again, burying the fang in his ring finger this time.

At the sound of his cry, Jennifer, a trained nurse, had come running. When she saw her husband struggling with the rattlesnake’s head, one thought flashed through her mind: he needed medical attention, now. She ran back into the trailer to get the car keys while Sutcliffe continued to yank at the snake’s head until finally the fangs came loose and he could fling the viper away.

Jennifer told her husband to get in the car. She wheeled out onto the broiling Texas asphalt, already on the phone with 911 dispatchers. They were a half-hour away from the nearest hospital and she had no idea which of the medical centres in the area held anti-venom. All she knew was that they didn’t have much time.

Slipping Away

Jennifer Sutcliffe had always been quick to act under pressure. In Texas, she was a nurse consultant, but back when she’d worked in hospitals she’d always been the go-to person for CPR—someone colleagues would turn to when competence and quick thinking could be the difference between life and death.

She’s known her husband for their entire adult lives. They’d met in the summer of 1993, when they were both students working at a nursing home. She’d liked his sparkling blue eyes and the fact that he was kind. The two became friends, then more.

They were married a couple of years later and went on to have a son and a daughter. Sutcliffe was handy, a builder and a tinkerer who worked installing heating and air conditioning. He always seemed to be helping out one neighbour or another.

In 2011, at the age of 34, Sutcliffe was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare and mysterious condition that causes the immune system to attack healthy nerve cells. The disease left Sutcliffe weak and exhausted, unable to work more than a few hours a day, but the couple got through it together. When they bought the house in Corpus Christi, it felt like the ideal situation. While she worked, he would slowly create their dream home.

Now, as Jennifer sped down the highway, she could feel that fantasy slipping away. On the phone, the 911 dispatcher was directing her down the highway to a spot where an ambulance would meet them to bring her husband to the nearest hospital. Mere minutes after being bitten, however, Sutcliffe was already feeling the effects of the venom coursing through his body. When he blinked, there was nothing but blackness. “I can’t see,” he said, panic in his voice, before passing out. Jennifer shook her husband with one hand while keeping the other on the wheel. Sutcliffe woke up, only to pass out again. Then he began having a seizure. The 911 operator told Jennifer to pull over and wait in front of a church for the paramedics.

Finally, after the longest 15 minutes of her life—during which Sutcliffe alternated between babbling incoherently and losing consciousness—the paramedics arrived. They rushed Sutcliffe into the vehicle and took off down the highway with Jennifer speeding behind. After just 10 minutes, however, the ambulance pulled over into the parking lot of an abandoned building. When Jennifer pulled up next to them, they told her that Sutcliffe was in bad shape. His blood pressure had plummeted, and they were worried he wasn’t going to make it to the hospital.

“We have to get the HALO,” one of the paramedics said. Instead of driving to the hospital half an hour away, they were sending for a helicopter that would get him into a different emergency room in 10 minutes. Moments later, the chopper touched down and whisked Sutcliffe away.

The Rattler’s Revenge

Rattlesnake venom is a miracle of evolution—a complex cocktail of enzymes and proteins that, when injected into a victim’s bloodstream, acts like a powerful blood thinner, destroying skin tissue and blood cells and causing internal hemorrhaging. A rattlesnake’s fangs are connected to venom glands at the back of its head. Snakes can control how much venom they inject, and because producing venom takes energy, they typically don’t want to waste it. When cornered, an adult rattlesnake will usually deliver a light defensive strike to scare off a threat.

A snake that has been decapitated, however, has nothing to lose. “Think about it like a Hail Mary pass,” says Christine Rutter. “This snake is pained, he’s scared and he’s going to do everything he can to defend himself.” And so the snake that bit Sutcliffe emptied its venom glands into his hand. The average snakebite victim is given two to four doses of anti-venom. In total, Sutcliffe received 26.

When Jennifer got to the emergency department at Christus Spohn Hospital Corpus Christi–Shoreline, about an hour and 15 minutes after her husband, she found a hectic scene. There were six or seven doctors working on her husband, desperately trying to get his blood pressure up. Just two hours after being bitten, Sutcliffe’s right hand was enormous and swollen, an angry red creeping up his forearm.

She watched with her nurse’s eyes as doctors gave him a host of treatments—cryoprecipitate and vitamin K to clot the blood, and dose after dose of anti-venom. Jennifer knew IVs: if a patient needed fluid quickly, you simply increased the flow, turning a drip into a steady trickle. But the doctors here had put the IV bag into an inflatable sleeve that they’d pumped up like a blood-pressure cuff, literally squeezing fluid into her husband’s body as fast as they could. She’d never seen anything like it before. The sight terrified her.

At 5 p.m., after five hours of working on Sutcliffe, the doctors came to a decision. Sutcliffe’s organs were failing—they needed to induce a coma and put him on a ventilator. Jennifer numbly agreed.

At around 3 a.m., one of the doctors approached her. Her husband wasn’t doing well. His blood pressure was still dangerously low. The mean arterial pressure (or MAP) that doctors were looking for was 65—anything lower and the heart can’t push blood through the body. They had Sutcliffe on the maximum dosage of four medications designed to increase his blood pressure, but his MAP refused to budge above 60. “We’re at the point where there’s nothing else we can do,” the doctor said. There was a good chance Sutcliffe wouldn’t make it through the night.

Jennifer felt her heart plummet. She somehow hadn’t registered the gravity of the situation. She went to her husband’s bedside and grabbed his hand. “You find that venom and you push it out of your body,” she ordered. “You can’t die.”

Over the next half-hour, she stood by her husband’s side in the ICU, her eyes glued to the monitor next to his bed. Slowly, miraculously, she watched as Sutcliffe’s blood pressure ticked up. It made it to 65, then 70. The doctors began taking him off the medications and his pressure remained stable. By sunrise the following day, the worst was over.

A New Perspective

On May 31, five days after the rattlesnake he killed nearly killed him, Jeremy Sutcliffe emerged from his coma and found himself in a strange hospital room. His mind was foggy. His entire body was swollen with more than 20 kilograms worth of water weight. Pain radiated from his legs, his arms, his bowels, everywhere. But as he looked around, he saw that he was surrounded by family: his daughter and her children, his son, Jennifer.

The next weeks were difficult. The mixture of venom and anti-venom had caused severe kidney damage, and Sutcliffe needed dialysis. The toxins had left him with gallstones, kidney stones and fierce abdominal pain. He was so weak he couldn’t stand. The medical expenses piled up—close to $60,000—so the couple started a GoFundMe account to pay for the battery of treatments. The fingers of Sutcliffe’s right hand were badly wounded; the doctors tried skin grafts but were unsuccessful. In the end, they were forced to amputate his ring and middle fingers.

For anyone else, the loss of two fingers would be devastating. But Sutcliffe didn’t see it that way. After getting a glimpse of the worst, he was feeling positive. About a month after the bite, his kidneys were working well enough for doctors to take him off dialysis. “I’d trade a couple of fingers for my kidneys coming back,” he said.

Lying in a hospital bed, slowly recovering, he’d had time to think. “When I first came to and things were all right, I’d cry a lot and think about all the dumb things I’d done, the people I’ve hurt,” says Sutcliffe. He remembered skipping his kids’ events or ignoring Jennifer while he was off working on a neighbour’s house. It wasn’t that he’d done anything so terrible—just that his new perspective suddenly made every misstep seem like a tragic waste. The experience had changed him. “The things that used to matter don’t feel like they matter as much,” says Sutcliffe. “My wife and my family seem so much more important now.”

In late June, he was released from the hospital and the couple moved back to their dream-home-in-progress. And one evening in July, they finally had the cookout they’d been planning. Their daughter and grandchildren came over, as did a neighbour. Everyone sat out in the garden, eating hamburgers, grilled corn and potatoes and enjoying the warm Texas air. The Sutcliffes paused to take it all in. This was their paradise, and no snake could change that.

Check out more Drama in Real Life from the pages of Reader’s Digest Canada.

I am a lifelong resident and historian of Tillsonburg, Ontario. It is said that Mary Ann Tillson, the wife of Tillsonburg’s first mayor and founding family, attended a lecture by Oscar Wilde in Woodstock, Ontario, on May 29, 1882. For me, this was an incredible connection between our town’s history and the world-renowned playwright and late-Victorian caricature of flamboyance and wit.

Oscar Wilde travelled across North America for the full year of 1882. In the late spring he journeyed to Canada and had a number of speaking engagements through Ontario.

Arriving in Quebec, he spoke two nights in Montreal and one night in Quebec City. He began his Ontario excursion in Ottawa, moved west to Kingston and Belleville, then Toronto, Brantford and Woodstock, finishing in Hamilton before returning to the United States. He came back to Canada in October that year and graced the Maritime provinces with his presence.

Wilde spoke on the second floor opera house stage in the Woodstock Town Hall. Reporting the event on June 2, 1882, the Woodstock Sentinel-Review stated: “Oscar Wilde, the boss showman of the day, made a great impression here on Monday night.”

Today the building is the Woodstock Museum National Historic Site. Knowing this, when I meandered through the second floor of the museum, I came upon the stage in awe. The room has changed greatly since he honoured the space and is now utilized as a community/work room. The nostalgia of this little-known historical gem is not lost on those who stand there, aware that Oscar Wilde had once stood there, too.

Interestingly, the hotel where Wilde spent his night in Woodstock, the O’Neill House (later the Oxford Hotel), is still standing just across the road from the museum. Sadly, many of the opera houses in the other cities where he visited through Ontario have been demolished, removing a tangible glimpse and connection to Wilde from their communities.

But, in this museum’s multi-purpose room, nearly 140 years ago, Oscar Wilde pontificated on the evolution of modern culture, fashion and decorative arts. Borrowing from the contemporary Arts and Crafts Movement he promoted the usage of handcrafted furnishings. Patrons were encouraged to employ local craftspeople and use local materials. This was a reaction to the artificiality of mass production of the late industrial age.

A New Way Forward

There was a growing rejection to the dark and stuffy, cluttered curtained rooms of the mid- to late-Victorian home. Wilde would become famous for modernizing art initiatives and theories towards the Aesthetic Art Movement. This type of design and decoration was based on local trades, geometrics (which would later connect with the Art Deco period), images and interpretations of flora and fauna. These could be accomplished by incorporating organic looking carpentry, metal work and stained glass into the home.

These applications are seen in the design and decoration of Annandale House in Tillsonburg. Built in 1880 by Edwin Delevan and Mary Ann Tillson, it served as their stately home for retirement. The house was designated a National Historic Site in 1997. Its designation was based on it being one of the best surviving examples of a personal residence in Canada using the principles of the Aesthetic Movement. Having lived near and worked in Annandale NHS, I have had the opportunity to explore, research and experience the beauty of its aesthetic interior.

The Aesthetics Movement touted that beauty should be seen wherever you look. Homes should be bright and with evidence of nature’s splendour on the inside of the home. The Tillsons employed these properties into their magnificent home. The exterior of the house is made up of polished blonde brick from the Tillson brickyard. The front hall uses local wood with varying hues creating unique geometric patterns. Images of flowers and birds adorn the ceilings of the dining room, parlour and library. You can look straight up from the grand staircase and see the painted parrot on the third floor ceiling. And, as an homage to Wilde and his favourite flower, you can find images of sunflowers often.

Wilde’s legacy has grown over the years but the memory of his appearances in North America, particularly in Canada, have been largely forgotten. Tillsonburg and Woodstock have direct connections to the man and his influence on art and culture. It is a pleasure for this historian to introduce you to accessible locations that you too can discover, associated with Oscar Wilde, in small-town Ontario.

Next, take a virtual tour of the most famous houses in every province.

What do a green glass room in the woods, rollable trees, a summer lodge and an energy efficient house have in common? They are all found at Reford Gardens (Jardins de Métis in French), about a 30-minute drive from Rimouski as one heads eastward into the picturesque Gaspé Peninsula region in Quebec.

Rain or shine, natural and man-made creations are impeccably readied to welcome visitors. The first time I visited the gardens was with my colleague, Achsa, on its rainy opening day for the 2019 season; we were attending a teachers’ conference and that was the only time we could go. Then, I returned last year with my nature photography-loving husband, Rob, in July.

Whether one’s tastes lean towards traditional gardens and babbling brooks, or the art installations of the contemporary gardens, anytime of the summer seems to offer something of interest there. The green glass room in the woods that people could enter, and the rollable trees that we could push along underground tracks, were part of the International Garden Festival, where various landscape architecture works are added each year, all inviting us to be very hands-on and “explore.” In fact, we were like kids in grown-up form, as we trampolined, climbed, swung in or entered several spaces, all nestled within the woods and the great outdoors.

The legacy of Elsie Reford is alive and well in Reford Gardens. Core to these gardens she envisioned and created in 1926 is her vast vacation home, Estevan Lodge, now housing exhibits about her summers spent there with her husband. In the exhibits, we can learn that with help from locals, Elsie designed the gardens and transformed the extensive property surrounding this salmon-fishing lodge. It took present-day visitors like us hours to see everything. Elsie’s handiwork amazingly spanned three decades.

ERE 132, the Eco-home constructed in Reford Gardens in 2015, is not only full of energy efficiency (something my husband can appreciate), but tastefully decorated in a cozy, modern style. It is both educational and quite literally, livable. I learned that you could stay overnight in this home. I don’t know what Elsie Reford would have thought of all this if she were alive, but as somewhat of an innovator in her time, I can only guess she would approve. (Take a look at 10 more unforgettable places to spend the night in Quebec.)

Whether young or old, Reford Gardens invites visitors to engage with nature in one form or another. We certainly created enjoyable memories on this vacation and took 544 photos in the process! The next time you are travelling through the northern part of the Gaspé Peninsula and spot a giant-sized Adirondack chair beside the highway—if you feel like exploring—turn in at Reford Gardens.

If you enjoyed this look at Redford Gardens, don’t miss our countdown of Canada’s most beautiful botanical gardens.

Every James Bond Movie, Ranked" width="295" height="295" />

Every James Bond Movie, Ranked" width="295" height="295" />

Surprising Science Behind Friendship" width="295" height="295" />

Surprising Science Behind Friendship" width="295" height="295" />