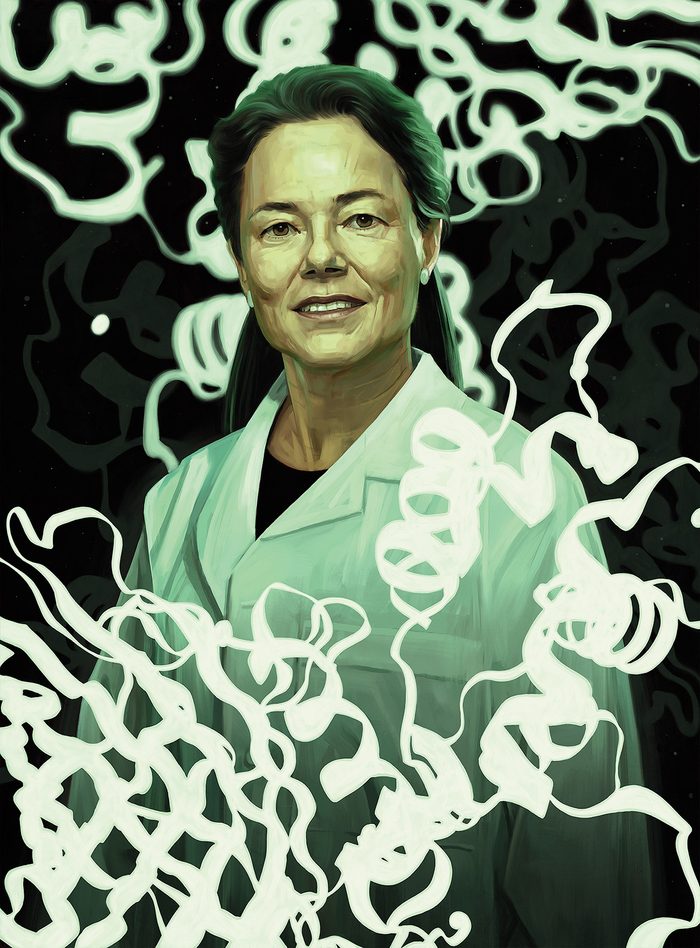

Dr. Carola Vinuesa was in her office at the John Curtain School of Medical Research in Canberra, Australia, one afternoon in August 2018 when she received a call that both changed her life and saved another. As a professor of immunology, Vinuesa immersed herself in the fascinating and complex world of genetics.

The call was from David Wallace, a former student at John Curtain whom she hadn’t spoken to in years. He presented Vinuesa with a scenario that was equal parts shocking, intriguing and devastating: An Australian woman named Kathleen Folbigg had been sentenced to decades in prison for murdering her four children, all infants, over a period of 10 years. The case had captivated the nation. Many were abhorred by Folbigg’s crimes; others questioned the veracity of her guilt.

Given the paucity of evidence used to convict Folbigg, asked Wallace, could Vinuesa’s research shed light on what actually happened to the children?

Over the next five years, Vinuesa and an international team of scientists would dedicate much of their lives to answering this question. Their findings would shake up Australia’s judicial system, raise questions about the treatment of mothers accused of killing their children and shine a light on the misuse of scientific evidence.

Folbigg, who was born Kathleen Megan Britton in Balmain, an inner-city suburb of Sydney, on June 14, 1967, was haunted by tragedy, instability and alienation from the very beginning. In December 1968, her father, Thomas Britton, stabbed her mother to death during an argument; he served 15 years in prison before being deported to his native England. Young Kathleen was shipped off to live with her mother’s sister in western Sydney.

Any hopes that Kathleen would have a warm and safe childhood were soon dashed. The girl’s aunt, known in court records as “Mrs. Platt,” complained to child-welfare authorities in spring 1970 that Kathleen was aggressive, impolite, unclean and preoccupied with masturbation—and that the strain of caring for her niece was causing her marriage to deteriorate. She no longer wanted the girl. Kathleen was not yet three years old.

Doctors determined that the girl had likely been abused by her father. She was also found to have an unusually low IQ, largely attributed to her withdrawn and restless nature. In September 1970, she was placed into the care of a foster family, Deirdre and Neville Marlborough, who lived in Newcastle, 120 kilometres north of Sydney.

At first she bonded with the family and settled into school. But the legacy of her catastrophic early years took its toll: She was caught shoplifting, left school early and struggled in her relationship with Deirdre. At 17 she left home and moved in with the family of a friend.

A year later she met a 23-year-old forklift driver named Craig Folbigg at a nightclub in Newcastle. Craig was tall with brown hair, a pronounced nose and an easy smile. Charming and chatty, he seemed like Kathleen’s rescuer. Together, they could make the home she had always needed. They married in 1987, when Folbigg was just 20, and rented an apartment in Georgetown, Newcastle. Folbigg found a job as a waitress at an Indian restaurant.

Craig was one of eight children and wanted a big family himself. Soon the couple was expecting. Thrilled, Kathleen Folbigg became protective of her unborn child: Craig was forbidden from smoking indoors, and Folbigg improved her diet. When Caleb was born in February 1989, Folbigg told people that she felt complete; after so many years of upheaval, she had a husband, a home and a baby.

But on February 20, 1989, tragedy struck. Folbigg found Caleb, just 19 days old, dead in his crib. An autopsy identified the cause of death as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Folbigg was devastated but not deterred, and she was soon pregnant again. When Patrick was born in June 1990, he underwent extensive testing, including a sleep study. The results were normal. Still, Folbigg was terrified for Patrick’s life.

It turned out that she had reason to be afraid: On October 18, 1990, four-month-old Patrick had what was known as an apparent life-threatening event, typically associated with oxygen deprivation. It resulted in brain damage, visual impairment and seizures for which Patrick was repeatedly hospitalized.

Caring for her disabled baby became the focus of Folbigg’s life. Few waking moments were spent without Patrick on her mind or in her arms. By February 1991, he was gone, too. The cause of death was listed as asphyxia due to airway obstruction related to his seizures.

Feeling that she was to blame for deaths of her two children, Folbigg fell into a deep depression. She decided that she and Craig needed to uproot their lives if they were going to beat whatever was plaguing their family. They sold their house and moved to Thornton, just north of Newcastle. Craig got a job selling cars, and Kathleen Folbigg found work at a baby-product retailer, a job that spoke to her heartbreaking desire for a family.

Sarah was born on October 14, 1992. She, too, underwent numerous tests, which didn’t find any problems. Sarah appeared to be developing typically, but Folbigg became obsessed with the possibility of losing her. The couple started to feel the strain.

One night, when Sarah was 10 months old, Craig saw Folbigg “growl” at Sarah as she tried to get the baby to fall asleep. She passed Sarah to him, telling him to deal with her. The next day, August 30, 1993, Sarah died. The autopsy concluded that the cause of death was SIDS.

What could possibly explain this terrible misfortune? In the wake of Sarah’s death, Craig became severely depressed, beyond the reach of his wife’s attempts to help. In a bid to change their luck, they bought a home in Cardiff, on the western edge of Newcastle, not far from Craig’s family.

The marriage started to crack under the strain. The couple separated repeatedly, but they reunited each time—whether through genuine mutual love or the shared bond of repeated trauma. They moved yet again, this time to the nearby Hunter Valley, and decided to have another baby.

Laura was born on August 7, 1997, almost four years after Sarah’s death. She was another healthy baby but was subject to even greater scrutiny, including a full panel of biochemical, blood and metabolic tests. For 12 months, cardiorespiratory monitoring indicated no problems with Laura’s breathing and heart function. As Laura’s first birthday approached, Folbigg planned a big party. She finally had a healthy baby, and her anxiety eased. The life she had planned for herself was coming to fruition after three heartbreaking false starts.

But the couple was once again falling apart. Kathleen Folbigg was a devoted mother, but Craig was concerned about her flashes of anger. One night in late February 1999, he noticed the strain between Folbigg and Laura, then almost 18 months old. “Oh, she’s got the sh—s with me,” Folbigg told him. “It’s probably over what I did to her last night. I lost it with her.”

At breakfast the next morning, March 1, Folbigg was struggling to feed cereal to Laura. She then pulled her out of the high chair, put her on the ground and told her to “go to your f——ing father.” When Craig went to work, Laura was watching television.

Later that morning Folbigg called Craig at work and apologized for losing her temper. She then took Laura to visit him during his morning break. Laura fell asleep in the car on the way home, and Folbigg carried her to bed. Laura died later that day. This time, the autopsy was inconclusive, though it did note that Laura had myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart.

Suspicion mounts

On the afternoon of March 1, 1999, shortly after Laura became the fourth Folbigg child to be pronounced dead in 10 years, a police officer met the couple at the hospital. The sudden deaths of the four Folbigg children, all apparently healthy at birth, suggested something sinister to police: It wasn’t a one-in-10-million unlucky happenstance. Could Folbigg have killed them?

As the police ramped up their investigation—including a search of the Folbiggs’ home—the couple’s relationship was once again on the rocks. They separated permanently in June 2000, still under police suspicion. On April 19, 2001, Kathleen Folbigg was arrested and charged with four counts of murder. She pleaded not guilty to all charges.

The jury trial began in spring 2003 at the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Sydney. In photographs taken during the trial, Folbigg looked as if she were sleepwalking—her eyelids heavy, her complexion pale.

The prosecution’s case laid out a cold take on the children’s deaths: Folbigg had asphyxiated each one. The circumstantial evidence seemed overwhelming. Each child was apparently healthy before dying in their own bed, and Folbigg was. both the last person to see each one alive and the one who had found them dead.

But the case wasn’t just circumstantial. After the couple had separated for good, Craig discovered his wife’s diaries. He later told the jury that what he read “made me want to vomit.” Crown lawyers used the diaries to allege that Kathleen Folbigg tended to “become stressed and lose her temper and control with each of her four children.” She was accused of frustration, impatience and even cruelty with her children.

The prosecutors suggested that more than 200 entries indicated that she didn’t love and hadn’t bonded with any of her children, and that motherhood left her so stressed and resentful that she was pushed to the darkest of acts.

June 3, 1990: This is the day that Patrick Allen David Folbigg was born. I had mixed feelings this day whether or not I was going to cope as a mother or whether I was going to get stressed out like I did last time. I often regret Caleb and Patrick, only because your life changes so much, and maybe I’m not a person that likes change, but we will see.

November 9, 1997: With Sarah, all I wanted was her to shut up and one day she did.

January 28, 1998: I feel like the worst mother on this earth, scared that [Laura] will leave me now, like Sarah did. I knew I was short tempered and cruel sometimes to her and she left, with a bit of help. I don’t want that to ever happen again. I actually seem to have a bond with Laura. It can’t happen again. I’m ashamed of myself. I can’t tell Craig about it because he’ll worry about leaving her with me.

Kathleen Folbigg’s conviction

The prosecutors argued that a grieving mother would not write these things. Even if the science surrounding the children’s deaths was inconclusive, the diaries were presented as clear evidence that Folbigg was an unfit mother. How far was the leap from unfit to violent?

Folbigg wasn’t the first woman convicted of killing her children under similar circumstances. Many of these cases were influenced by Roy Meadow, a British pediatrician who developed a theory that became known as “Meadow’s Law”: One sudden infant death in a family is a tragedy, two deaths are suspicious, and three are murder unless proven otherwise. Charles Smith, a Toronto pediatric pathologist and a go-to prosecution expert in criminal trials of people accused of mistreating their children, used a similar approach. Meadow and Smith had inverted the common-law tradition of presumption of innocence.

Both men have since been discredited, and many of the people they helped convict were later exonerated, but the damage was extraordinary. Sally Clark was a British lawyer convicted of murdering her two infant sons in 1999. A later review found that Meadow had misrepresented statistical evidence at her trial, and a pathologist had withheld evidence that pointed toward natural death. Clark’s release in 2003 prompted a review of hundreds of cases in the U.K., and several other mothers had their convictions overturned.

But the assumption of guilt informed similar cases. On May 21, 2003, Kathleen Folbigg was found guilty of three counts of murder, one count of manslaughter and one count of inflicting grievous bodily harm. The following October she was sentenced to 40 years in prison, with no chance of parole for 30 years, and was incarcerated at Silverwater Women’s Correctional Centre in Sydney. She was 35 years old. On appeal, her sentence was reduced to 30 years with no chance of parole for 25 years.

New evidence emerges

Tracy Chapman, a childhood friend who had largely drifted out of Kathleen Folbigg’s life, was galvanized by her arrest. As she followed the trial, Chapman became convinced that Folbigg would be found not guilty. Shortly after the conviction, she reached out to Folbigg. She called the lawyers and read through transcripts, desperately trying to figure out how her friend could be exonerated.

She and Kathleen Folbigg mostly communicated through long letters, in which Folbigg detailed her day-to-day life in prison. Most strikingly, Folbigg—whom Chapman describes as an animal lover with a terrific sense of humour—hadn’t lost her compassion or decency, even as she struggled with her grim reality. “She’s got a strong moral compass,” says Chapman. “And I supported her to not allow the system to eat that up.”

Other people also started to question Kathleen Folbigg’s guilt. One of the earliest dissenting voices came from Emma Cunliffe, an Australian working on her PhD in law at the University of British Columbia. She approached the Folbigg case through a feminist lens, part of an emerging consensus among some scholars that investigators and prosecutors were prone to discriminatory reasoning against women—particularly with mothers accused of harming or killing children.

As Cunliffe reviewed the trial records, she was disturbed that so many people involved in the case were certain of her guilt even though there was no evidence of homicide. She also found the use of Kathleen Folbigg’s diaries to be both highly prejudicial and misleading.

“The Crown’s case was that the unexplained deaths of four children within the same family, coupled with the diary entries and evidence about Kathleen Folbigg’s tendency to become frustrated, were sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Kathleen Folbigg had killed each of her children,” Cunliffe wrote in the Australian Feminist Law Journal in 2007.

In 2011, an academic journal asked Stephen Cordner to review Murder, Medicine and Motherhood, Cunliffe’s book about the case. Cordner, a forensic pathologist in Melbourne, had been following a similar case from 2007 in the Australian state of Victoria.

Carol Matthey, a 27-year-old mother living in the city of Geelong, was charged with murdering her four children. The crown alleged that each one was deliberately suffocated and that Matthey had “little regard” for her children, using them as pawns in her relationship with her partner. Charges were ultimately dropped due to insufficient evidence.

As Cordner reviewed Cunliffe’s findings, he was struck by the similarities to Matthey’s case—and the sense that something was deeply off about Folbigg’s conviction. He told the University of Newcastle Legal Centre, which had taken on Folbigg’s case pro bono, that he wanted to look into the conviction. In his 100-page report, Cordner wrote that the pathology reports offered no evidence to support the conclusion that the children had been murdered.

He also pointed out that the prosecution had used Folbigg’s diaries to portray her as a bitter mother who was prone to lashing out uncontrollably, but the children had no physical injuries. Laura’s teeth, for example, should have left a mark on the inside of her mouth under the pressure of suffocation. How could a mother act so violently yet kill her children so gently?

As the years passed, more medical and legal experts raised doubts about Folbigg’s conviction. The campaign to exonerate her took a crucial turn in 2018, when Carola Vinuesa entered the picture. David Wallace, the former John Curtain School of Medicine student who had become a commercial litigator, had been following the case with increasing unease about the lack of evidence to support the conviction. He called Vinuesa and asked: Was it possible that whole-genome sequencing, the process of determining an individual’s full DNA profile, might shed light on the deaths of the Folbigg children?

Vinuesa agreed to look into it. First she had a colleague visit Folbigg in prison and do a cheek swab. When Vinuesa sequenced Folbigg’s DNA, she discovered that she had an extremely rare mutation of the CALM2-G114R gene, associated with cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac death. Had Folbigg passed this potentially deadly mutation on to her children?

To get a fuller picture of the children’s genetic history, she wanted to sequence Craig Folbigg’s DNA. He refused to provide a sample, maintaining that his now ex-wife was guilty and declining to be part of efforts to free her.

Folbigg’s lawyer presented the findings of Cunliffe, Cordner and Vinuesa to Mark Speakman, the attorney general for the state of New South Wales, and in August 2018, he announced an inquiry. The next year, Reginald Blanch, a former chief justice of the District Court, produced a report of more than 500 pages, poring over the details of Folbigg’s life and the arguments and evidence presented at her trial. Folbigg’s supporters were stunned by its conclusion: “I find no error or procedural irregularity in the trial process that causes me to have a reasonable doubt as to Ms. Folbigg’s guilt,” Blanch wrote.

Folbigg, who had been in prison for 16 years at this point, had always maintained her innocence. It was unclear what, if anything, could clear her name. The report “looked like that was slamming the door,” says Cordner.

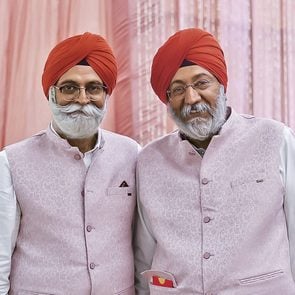

Pressing on, Vinuesa contacted world-renowned geneticist Peter Schwartz at the Auxological Institute in Milan. In a remarkable coincidence, he had recently written about a similar case involving two siblings who carried the same mutation as Kathleen Folbigg had, on one of the other CALM genes. One child had died, and the other went into cardiac arrest but survived.

Schwartz reached out to colleagues in Denmark. Mette Nyegaard, professor of biomedicine at Aarhus University, and Michael Toft Overgaard, professor of bioscience at Aalborg University, had made a similar discovery seven years earlier: Members of a Swedish family with a history of sudden cardiac deaths carried an extremely rare mutation in another member of the CALM gene group associated with sudden death in childhood. Both cases bolstered the theory that the deaths of the Folbigg children were not necessarily the result of sinister acts.

Vinuesa realized that investigators had concluded that the Folbigg children must have been murdered because the odds of them dying of natural causes were astronomical. But when these deaths are linked with a genetic factor, the picture shifts dramatically. “Then it’s a one-in-16 probability, not one in 73 million,” Vinuesa says.

She set about gathering the DNA of Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and Laura, drawing from decades-old samples collected either when the children were born or during their autopsies. Her analysis found that the CALM2 mutation had been passed along to Sarah and Laura. Caleb and Patrick, meanwhile, shared another exceedingly rare mutation in a gene known as BSN, which has been linked to lethal epileptic seizures.

As word spread of the growing evidence that all four Folbigg children had died natural deaths, 90 eminent scientists from around the world, including Nobel Prize winners and the president of the Australian Academy of Science, signed a petition in 2021 demanding a new inquiry into Kathleen Folbigg’s conviction.

Meanwhile, Peter Yates, a former investment banker who served on the boards of some of the country’s most important institutions, heard Vinuesa talk about the Folbigg case and was an immediate convert to the cause. He became what he calls “the de facto chairman of Team Folbigg,” lobbying politicians and bringing in a public-relations rm to shift the public’s perception of Folbigg from serial killer to wrongly incarcerated and grieving mother.

Media coverage reached a fever pitch. Headlines had once called Kathleen Folbigg “Australia’s worst female serial killer”; now her incarceration was portrayed as a grim miscarriage of justice.

In May 2022, following enormous pressure from the public and the scientic community, Governor of New South Wales Margaret Beazley ordered a second inquiry on the advice of NSW Attorney General Michael Daley. Just over a year later, the head of the inquiry, retired judge Thomas Bathurst, concluded that there was reasonable doubt that Folbigg was guilty. The governor signed a full pardon for Folbigg and ordered that she be freed.

On June 5, 2023, Kathleen Folbigg was released from prison. She was 55 years old and had been incarcerated for 20 years.

She spent her first night of freedom at Chapman’s farm in northern New South Wales, eating pizza and drinking Kahlua and Coke. “We didn’t actually say very much,” says Chapman. “There was a kind of profoundness in the silence.” For so many years, the friendship had been dominated by a single, exhausting goal: getting Folbigg out of prison. Now they could finally rest.

“A long way to go”

In November 2023, the final report of the second inquiry recommended that Folbigg’s convictions be overturned, and the following month the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal formally quashed them.

For many of Folbigg’s supporters, her wrongful conviction has raised questions about how many other innocent women might be languishing in prison due to faulty science and mischaracterization of their actions.

“We’ve got a long way to go,” says Cordner, who recently published a new book, Wrongful Convictions in Australia: Addressing Issues in the Criminal Justice System. Legal experts have called on the Australian government to appoint an independent body to review wrongful convictions—similar to ones in England and New Zealand.

“I hope that no one else will ever have to suffer what I’ve suffered,” Kathleen Folbigg, wiping away tears, told the media after her convictions were overturned. “My children are here with me today, and they will be close to my heart for the rest of my life.”

Next: How DNA testing is solving cold cases—and reuniting families.

I recently read that a new high-speed train route had opened in Laos at the end of 2021. The Lao-China Railway can get you the 150 kilometres from the ancient capital of Luang Prabang north to the Chinese border in just 90 minutes. It carries more than 1.5 million passengers a year, a game-changer for a country with very little transportation infrastructure.

As someone who has visited this remote corner of Laos, I wondered: What fun is that sort of speed when you can take three days to do pretty much the same trip by boat—never knowing if you’ll actually get there?

It was the spring of 2017, and my husband, Jules, and I had just spent two weeks travelling around Laos. We had poked around the humid, sprawling capital, Vientiane, in the south and explored the fascinating Plain of Jars in the middle of the country. We were really enjoying it—the people were kind, and it wasn’t as touristy as we knew Vietnam, the country we planned to visit next, would be.

We saved Luang Prabang, Laos’s historic former capital, for last. Located at the confluence of the Mekong and the Nham Khan rivers, the UNESCO World Heritage Site was quiet, with several gilded Buddhist monasteries. Its well-preserved French colonial buildings date back to the first half of the 20th century, when Laos was part of French Indochina.

We strolled the peaceful back streets and colourful craft markets and climbed Phousi Hill to take in the view. Relaxing at a bistro across from a wat (Buddhist temple), we watched saffron-robed monks stroll by as we enjoyed coffee and croissants, another vestige of France’s colonial regime. At a bamboo-stilted riverfront café we ate traditional Lao larb—spicy ground pork or chicken mixed with fresh seasonings—served with the refreshing local brew, the rice-based Beerlao.

As the sun sank on the Mekong River, we watched multicoloured longboats glide by while the breeze carried the deep, soft sounds of the wats’ gongs. I couldn’t think of a more serene place to spend our final days in Laos.

Then things took a sharp turn. Walking down Luang Prabang’s main drag on our second-last day, Jules spotted a trekking outfitter that offered a multi-day hike among the Akha hill tribes outside the small city of Phongsali. It would mean travelling to the mountainous frontier area near Laos’s northern border with China and Vietnam.

Jules and I had talked about visiting the area once we got to Vietnam. We had seen photos of Akha women wearing silver-beaded head-dresses, and we were intrigued by the fact that the ethnic minority Akha people, along with other tribes living in the mountainous regions of Laos, Myanmar, China and Vietnam, had managed to maintain their traditional way of life.

But we’d been having second thoughts. Though numerous tour companies ran treks to the Akha villages in Vietnam, we weren’t big fans of overly planned group tours. Maybe a hike to the Akha villages in less-touristy Laos, just the two of us with a guide, would be more our style.

“Let’s not go to Vietnam yet,” Jules said. “We should see more of Laos.”

I liked the idea, but I needed to know how we’d get to northern Laos before committing to it. Phongsali was so far away and the roads weren’t great. Our Lonely Planet guidebook had very little information about that part of the country.

Maybe we could go by plane?

At the local tourism office we were told that Lao Airlines did not fly there at that time of year because of thick smoke: It was “burning season” in central Laos, when farmers torch their fields ahead of planting.

We could catch a bus, but it would take 15 hours, much of it on mountainous switchbacks. What was worse, reviews on Trip-Advisor had tales of the bus drivers falling asleep at the wheel. That didn’t sound like much fun.

We called a trekking outfit in Phongsali on WhatsApp. “You might be able to get a riverboat,” the owner, Sivongxay, told us.

“But I’m not sure. Call me if you make it here and we’ll take you on a trek!”

So we would just head into the unknown? I’m the type who likes to plan my journeys, but the idea of travelling by river sounded very appealing. I tamped down my reservations and said to Jules, “Let’s give it a try.”

The local tourist office told us that any boat journey that might get us to Phongsali would be on the Nam Ou River. To get to the river, we’d need to take a four-hour minibus ride to a town called Nong Khiaw. Seemed reasonable.

“And from there?” I asked the young tourism officer.

“I think boats go north, but I don’t know how far,” she responded. We bought the minibus tickets anyway, for the next morning.

That evening in our guesthouse we hit Google to find out about boat rides on the Nam Ou. We had no luck. While there was decent information about the popular tourist regions of Laos, there was hardly anything about the country’s farther reaches.

One reason for this is that some areas are littered with unexploded bombs dropped by the Americans during the Vietnam War, as a deterrent to Viet Cong using the Ho Chi Minh Trail through eastern Laos. Nearly five decades later, the still-live bombs, partially or fully buried, remain a daily danger to farmers and road builders.

Our journey into the unknown had to start somewhere, and the first step was catching the minibus the next morning. We arrived in Nong Khiaw at about noon and walked to the riverboat ticket office. It was closed. But according to a schedule posted outside the office, a boat did head north once a day—and today’s had just departed.

There are worse places to be stuck for a night: Nong Khiaw, which had a population of around 3,500 at the time, was surrounded by misty, jungle-covered limestone karst formations. We spent much of the afternoon exploring the town. Later we found a guesthouse that served noodles and Beerlao, plugged our phone into their speaker system, put on Nova Scotia band Joel Plaskett Emergency’s Ashtray Rock and watched a mother washing clothes in the river while her kids splashed around, jumping to the beat of the music.

The next morning, we arrived at the boat office at 9:30. We were eager to find out how far these boats actually went and where in Laos we might end up sleeping that night. We learned that one leaving at 10:30 would take us to the village of Muang Khua, a five-hour journey.

Would there be another boat from there to Phongsali? We couldn’t get an answer, and our map of Laos, which was short on details, didn’t help. The map did have one important piece of information: Muang Khua had a tourist office. We were confident our questions would be answered once we arrived there that afternoon.

We took the front two seats of the blue wooden longboat and placed our packs at our feet; a dozen young backpackers piled into the boat and sat down behind us. Two hours later, at the first stop, everyone except us got off. With the entire boat to ourselves for the next few hours, we sat back to enjoy the rest of our journey.

And what a journey it was, like something out of an Indochina period film: The Nam Ou was wide, smooth and brown, and the clear sky had a misty quality above the lush banks. We munched on our packed lunch—water, apples and baguettes with Laughing Cow cheese—and sipped boxed red wine from our travel mugs as we slipped past tall, rounded karst landforms and quiet villages of bamboo huts where goats wandered the dusty lanes.

Children shrieked as they ran along the riverbanks in the shallow waters. Mud-covered water buffalo ambled down to cool themselves too. Women filled their woven baskets with the greens they grow on the edge of the river at this time of year, when the water is low.

It was truly a blissful, magical boat trip that we treasure even more now. Because although we didn’t know it at the time, we were among the last to experience this particular river journey, one that people had been taking for centuries. Just eight months later, in late 2017, a massive hydroelectric dam on this stretch of the river would be completed, ending a way of life for several villages whose lifeblood was the Nam Ou.

One by one, dams were being built along the river as part of the Belt and Road initiative, China’s massive international infrastructure program. Many villagers had been relocated, river transport was reduced to the short stretches between the dams, and fishing and local riverside agriculture had taken a hit, reducing local food resources.

We later realized that this was why we had so much trouble finding information about travel on the river: The dams were being built so quickly that it was hard for anyone who didn’t live in the area to know what stage each one was at.

Just before 4:30 p.m. we stepped off the longboat at Muang Khua and walked up the steep road, packs on our backs, in search of the tourist office. We found it—just as the young woman who worked there was locking up. Uh-oh. Still hoping to travel onward that day, we asked, “Is there a boat to Phongsali? A bus?” She shook her head and pointed to a sign that said the tourist office would open at 8 a.m. the next day. We were staying the night.

Walking the dusty roads along with strutting chickens and the odd wandering dog, we came across a concrete bunker of a hotel, checked in, dumped our bags and went in search of a café where we might find other tourists we could ask about getting to Phongsali. We were in luck: At the only place in town with an English menu, we met a British couple in their 60s—and they had just come from Phongsali!

“Don’t take a boat any farther north,” the man warned. They had done it, but to get to the next stretch of the river, they had to bypass one of the massive new dams; they’d spent two hours in the back of a songthaew (a modified pickup truck) on a rough road, hanging on for dear life. The road was packed with heavy trucks loaded with building materials.

“We kept getting hit with gravel coming off the trucks,” the woman explained. “Once you get to the other side of the dam, there’s no guarantee a boat will be waiting to take you the rest of the way. If there isn’t, you’re sleeping on the side of the river.”

Instead, they said, we should take the eight-hour bus trip from Muang Khua to Phongsali. That definitely sounded better.

The next morning, we awoke to the sound of a tinny loudspeaker. It was blaring an authoritative female voice speaking in Lao and some really jarring marching music. We learned later that it was a daily update from the central Communist government.

We got to the tourist office at 8 a.m. on the nose. A dapper middle-aged man arrived and unlocked the door. Luckily for us, he spoke English. “Good morning!” I said with a hopeful smile. “What time is the bus to Phongsali?”

He looked at his watch. “It left at 7:30,” he replied. Jules and I stared at each other, crestfallen. It was the bus from Luang Prabang, the man explained (the 15-hour journey we had earlier decided not to take). It came just once a day.

Now what? “Time to call Sivongxay,” Jules said, referring to the trekking guide we were hoping to meet up with in Phongsali. “Maybe he knows another option.”

Sivongxay paused after Jules explained where we were. “I think there’s a bus that starts in Vietnam and goes through there,” he said. “It comes up here a few times a week. I don’t know if there’s one today. If there is, it’s maybe at noon? Or 2 p.m.? You have to flag it down.”

Full of doubt, but with nothing better to do, we walked to Muang Khua’s main street. Sivongxay had told us to look for a bus with a sign that said “Phongsali” on the front. (Would “Phongsali” be in English letters, Vietnamese characters or Lao script? And would the “bus” be a full- size coach, a minibus or a songthaew? We had no idea what to watch for.)

It was only 8:30 a.m. so we had hours to wait, maybe for nothing. We explored the town on foot, and later that morning we found a spot on the main street with some shade and two small plastic stools, complete with a litter of newborn puppies and their mother underneath. To pass the time, we read our books and drank thick, strong Lao coffee. We negotiated with a woman who lived nearby to use her outdoor bathroom—let’s just say it was rudimentary—in exchange for a few kip (less than one cent Canadian).

But mainly, as the sun moved across the sky, we kept an eye to the east—the direction of the Vietnamese border some 70 kilometres away—watching for buses. There were plenty of all shapes and sizes, most with Lao script on the front. As noon approached, Jules started jumping up to stop buses as they barrelled into town stirring up dust.

“Lodme Phongsali?” he asked the drivers, using the Lao word for “bus.” Each time, the driver shook his head and sped off.

We were pretty much resigned to staying on the plastic stools for the rest of the afternoon, knowing that the bus might not come and we’d be back in the concrete bunker that night. We grabbed a snack for lunch from a nearby vendor and settled in. Then things changed—fast.

Looking up as yet another bus approached, we couldn’t believe our eyes: The sign in the front window read “PHONGSALI.” But it was flying past us. We threw down our lunch, grabbed our packs and scrambled behind the bus, waving frantically in its dust. You can’t imagine our relief when it slowed to a stop.

“Lodme Phongsali?” we asked the driver in unison.

“Yes, each 40,000 kip,” he said— about C$5. After paying, we were waved onto the minibus packed with sacks of rice, construction materials and other goods from Vietnam.

It was the start of another journey into the unknown.

What followed felt like a visit to another planet. We arrived in Phongsali that evening, and the next day we met Zheng, a guide Sivongxay had hired for us. To start our trek to the Akha hill tribes’ region, Zheng (who spoke Lao, English and the Akha language) shepherded us onto a minibus for a half-hour ride to the edge of the Nam Ou River. Yes, we were returning to the same river that had taken us from Nong Khiaw to Muang Khua.

A longboat took us farther north, and we were dropped off after an hour or so at a muddy landing point. Then, with small packs on our backs, up, up we climbed in the sweltering heat through a thickly forested mountainside toward the clouds and the cooler air of the Akha villages, where the views over the green hills are misty.

Over the next three days, we saw no other foreigners. As arranged by Zheng, we stayed with local families in the villages we visited and learned about the traditional existence of the Akha—one in which the men hunt for food with slingshots while the women do just about everything else.

That includes growing cotton, turning it into thread, then using the thread to make fabric. After dying the fabric indigo, they make a long, embroidered jacket that, along with leggings and an elaborate headdress, they wear on their wedding day—and every day after that. The women’s tasks also include collecting water in huge bamboo pipes, which they lug on their backs up the steep hills.

Bathing took place in the centre of each village, with designated hours for women and men to give everyone a measure of privacy. At least that was the theory. Neither Jules nor I was able to wash without drawing a crowd. We did our best to cover ourselves with towels.

Meals, which we ate at people’s homes, consisted of rice, foraged greens and whatever meat was available—often chicken, but we had squirrel soup for dinner once, seated on short stools on a dirt floor while pigs and chickens hovered nearby, waiting for scraps. (Jules was thankful for their services when a squirrel skull ended up on his spoon; he quietly deposited it on the floor behind him.)

To an outsider like me, the lives of the Akha people look difficult. Yet they are managing to keep their culture alive in the quiet hills, up in the clouds, and avoid being assimilated into mainstream Lao, Chinese or Vietnamese societies. Fortunately, in many villages the local chief has a motorbike, giving them access to markets and emergency healthcare when necessary.

I’m thankful to have travelled a lot in my life, and whenever I am asked about memorable trips, I always mention this one-of-a-kind, never-to-be-repeated experience. I am so thankful there was no railway, high-speed or otherwise, to northern Laos back then. Our snap decision to abandon our original plan for one that literally had no road map added a layer to life I didn’t realize I’d enjoy so much.

In the end, the journey was as rich as the destination. By willingly plunging into the unknown, I discovered what truly makes you feel alive: the surprises waiting around the next bend on a river less travelled.

Next, read about 20 of the greatest once-lost cities—and not just Machu Pichu and Pompeii.

After suffering a concussion in January 2023, Nicolle Weeks spent nearly a year fighting symptoms such as migraines, fatigue and dizziness. Initially, the 43-year-old didn’t realize how severely she had hit her head.

“I was walking on the sidewalk, and I slipped on some black ice, fell backward and bounced my head off the ground,” she says. She lay flat on her back with her arms out for a minute in shock.

Satisfied she wasn’t injured, she dusted herself off and hurried to meet a friend for brunch. While there, she felt far away and dazed when her friend was talking. But it went away, and she didn’t think much of it.

It wasn’t until one week after her fall that Weeks was officially diagnosed with a concussion. That delay in treatment could be one of the reasons her symptoms persisted for so long.

Previously, doctors prescribed the “dark room” treatment—total rest in the dark while avoiding all mental stimulation. But thanks to recent research, we now know that too much rest and isolation can be harmful for recovery and that the best approach is somewhere in the middle: active rest. This slow and progressive return to activity helps patients recover faster and lessens the risk of long-term damage.

Here’s what doctors have learned, and what you need to know.

What happens during a concussion?

The brain is protected by shock-absorbing fluid and, outside that, the skull. In a concussion, the brain bounces around in the skull, accelerating, decelerating or rotating. This creates a cascade of impacts. The neurons in the brain are rattled, and between those neurons, the axons—thin fibres that transmit electrical impulses—stretch or break. The impact can also decrease blood supply to the brain and damage the neurons’ mitochondria, which create energy.

Inside the brain, it’s like an earthquake has happened. Everything is still standing, but there are cracks in the roads and in building foundations.

This microscopic damage has big consequences—that’s why a concussion is also known as a traumatic brain injury. The brain spends a lot of energy trying to repair itself and, combined with the decreased blood supply and mitochondrial damage, this causes extreme fatigue. Other symptoms may follow, like headaches, memory problems, irritability, insomnia and trouble with balance and visual processing.

Decades ago, the public had a “walk it off ” attitude toward concussions. That’s changed, thanks in part to an increased awareness about the long-term effects. The 2015 film Concussion tells the true story of Dr. Bennet Omalu, a forensic pathologist studying chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain disorder caused by repeated head injuries. CTE causes cellular degeneration in the brain and symptoms such as impaired judgment and dementia.

The disease can only be confirmed during a post-mortem autopsy. In recent years several former NFL players have been found to have had it, including former Denver Broncos player Demaryius Thomas and former New York Giants player Frank Gifford. Last June Henri Richard, a former NHL player for the Montreal Canadiens and Hockey Hall of Famer, was posthumously diagnosed with CTE. He died from Alzheimer’s disease in 2020.

Even though they’re the most high-profile examples, professional athletes aren’t the only ones who suffer from concussions. Each year, about 400,000 Canadians get concussions. Among those aged 20 to 64, 30 percent of concussions are the result of a fall, followed by sports (21 percent), work-related incidents (15 percent) and automobile accidents (11 percent). Among Canadians 65 and older, falls are by far the most common cause, at 61 percent.

The end of the dark-room theory

The dark-room treatment, which until recently was the standard prescribed by most doctors, involved patients resting in darkness and without any mental stimulation, until their symptoms subsided. This suggestion came out of studies in the 1990s and early 2000s that found when athletes with concussions continued with high levels of activity, they recovered more slowly than those who rested.

After a concussion, the brain uses a lot of energy for recovery—that’s why a common symptom is fatigue. So doctors and researchers concluded that doing as little as possible, both cognitively and physically, would free up energy for the brain to fix itself.

But people who spend more time in a dark room—sometimes called “cocooning”—are also more likely to experience anxiety, depression and sleep problems. Their bodies get weaker due to underuse, as well.

Additional research began to show that moderate levels of activity might be more beneficial. A 2008 study published in the Journal of Athletic Training found that athletes who did moderate amounts of activity after a concussion, such as returning to school and going back to sports practices, performed better on tests of their memory, reaction time and visual motor speed than both those who exerted themselves more and those who did very little. More studies followed supporting the idea that there is a sweet spot in terms of post-concussion activity.

Active rest: The stepped solution

“Science and research have evolved over the past decade, showing that when you stop doing activity altogether, that actually hinders your recovery process,” says Shelina Babul, a sports-injury specialist and clinical associate professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of British Columbia. The active-rest approach to concussion recovery promotes a slow increase in activity, starting with a day or two of light daily movement, and gradually adding activity, building to a full return to normal, unrestricted activity.

Despite this new research, much of the public—and even many doctors—still don’t know about the new best practices for concussions, says Babul. That’s why she created a four-step Concussion Awareness Training Tool. “I have amazing research colleagues,” she says. “But it takes an average of 15 to 17 years for scientific research to get from bench to bedside”—to make it from the lab into everyday use by doctors, in other words.

The training tool, which is intended to educate the public, physicians, caregivers and coaches, includes progressive plans for people to get back to their everyday lives. People who have a concussion should always go see their family doctor. Then they can work together through the four steps.

Step one should be observed for a maximum of 24 to 48 hours. Patients are encouraged to sleep, avoid screens and driving, and continue to perform regular activities at home, such as housework and light walking.

At step two, patients can resume light-to-moderate aerobic activity, such as stationary cycling, brisk walking and gardening, and they can gradually reintroduce screens.

Once a patient can tolerate moderate aerobic activity, they can move to step three, which involves returning to work or school and resuming most of their normal activities—except for sports that might give them another concussion through a head impact. If doing those normal activities causes their concussion symptoms to return, they should stop and try again the next day. Finally, at step four, once they can do all that and have clearance from a health-care professional, patients can go back to normal, unrestricted activity, including playing sports.

The goal is to keep people in their window of tolerance, says Babul. Doing too much too soon can push their brain into overload, so it’s important for people to listen to their body.

Dr. Charles Tator is a neurosurgeon and the director of the Canadian Concussion Centre in Toronto. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and a member of the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame for his work on concussions and safety in sport.

Tator suggests limiting alcohol and staying away from cannabidiol (a cannabis product). “It seems to prevent the production of the good chemicals in the brain from doing their job,” he says.

Getting good sleep can also help, which might mean staying away from caffeine or tweaking your sleep hygiene. People who have been concussed are also more likely to have sleep apnea, says Tator, and should be evaluated for the condition if it’s suspected.

Long-term effects

“Recovery from concussion is not as quick as we used to think it was,” says Tator. While we now know that most people will recover in roughly four weeks, an estimated 30 percent of people will experience symptoms for longer. For some, the symptoms can even be permanent.

“No two concussed patients are the same in terms of the number of symptoms, the type of symptoms and their recovery potential,” says Tator. “Each person requires individualized care, and it’s usually from more than one health-care professional.”

People who experience vertigo as a major symptom, for example, need to see a vestibular physiotherapist, while anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder would be treated by a mental health specialist.

Other factors that affect recovery include the force of the impact and whether you’ve had a concussion before. Having more than one increases your risk for permanent damage.

More than a year after her concussion, Weeks is back to her busy life. But she still has some symptoms, such as headaches and dizziness. She wishes she had recognized the signs of a concussion sooner and can’t help but feel that a slow and stepped approach would have made a difference in her recovery.

That’s why education and awareness are so important, says Babul. “People who follow the right guidance and management tend to recover uneventfully, and those who don’t and continue to do their activities continue to tax their brain and are likely to have long-term, persisting symptoms,” she says. “The key is to recognize it immediately and know what to do.”

Next, here are 7 concussion symptoms you should never ignore.

Ah, the first signs of spring—and the first sign of seasonal allergies. It could be the buds on the trees or the warm sunshine. Or maybe you know it’s spring because your nose is running, you’re sneezing and your eyes are red and itchy.

More than nine million Canadians suffer from seasonal allergies, which can start as early as February on the west coast and last well into the summer months. They can be triggered by pollen from grass, plants such as ragweed and goldenrod, and budding trees such as birch and maple.

“I’ve had allergies for 10 years, but they have been getting worse over the last few seasons,” says Toronto-based Patrick Boyd. The 30-year-old isn’t the only one experiencing a spike in the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, which typically include a constantly running nose, watery, burning or itchy eyes and a scratchy throat. Across the country, seasonal allergies are on the rise as the peak pollen months start earlier, last longer and have become more intense. In 2023, Toronto experienced its worst allergy season of the last five years.

“We have seen pollen getting worse in Canada,” says Daniel Coates from Aerobiology Research Laboratories, a Canadian company that monitors airborne allergens (and provides pollen forecasts to the Weather Network). “You have cycles up and down, but if you do a trend line between all the years of data, you can see that pollen levels are rising,” he says.

Experts believe that climate change could be to blame. “What’s really been throwing everything off is the fact that our winters are lasting longer, and then we get thrown into basically summer temperatures,” says Dr. Anne Ellis, a clinician-scientist and chair of the division of allergy & immunology in the department of medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

This sudden change in temperature causes the trees to panic and “bomb” us with pollen instead of slowly budding and blooming, she says. And, since the trees are releasing pollen much later in many areas across the country, they are now overlapping with grass-pollen season. “For people who are allergic to both, they’re getting a double whammy,” says Ellis.

To make matters worse, allergic rhinitis is aggravated by the very thing driving climate change: air pollution. Research from Ellis’s lab has shown that diesel exhaust makes ragweed allergy symptoms much worse. “If you’re in an urban area with traffic-related air pollution, this is likely to intensify your symptoms,” she says. (Interestingly, many cities also unwittingly exacerbate the air-quality problem by planting too many male trees—which release lots of pollen—since they don’t produce messy fruit or flowers, she says.)

Fortunately, you can minimize your exposure on peak pollen days. First, to know when those days are going to be, follow the pollen forecasts from your local weather source. Then, when tree, grass or weed pollens are in full force (usually between late spring and mid-summer), practise good allergy hygiene by not hanging laundry outside to dry, keeping windows closed and installing a HEPA filter on your furnace. Exercising indoors, delegating yard work and gardening chores that stir up allergens and showering after being outdoors will all help to minimize your exposure.

Despite, or maybe in part because of, how common spring allergies have become, we tend to dismiss them as just the spring sniffles. But this does a disservice to people who are suffering with the symptoms, day in and day out, sometimes for months at a time, says Ellis. “Nobody dies of hay fever, but it has a huge impact on quality of life,” she says.

Boyd describes often feeling irritable due to the discomfort in his eyes and nose. “Allergies also give me headaches,” he says. Like roughly three-quarters of people with allergic rhinitis, he has never seen a doctor about it, but he says his allergies have gotten so bad that he’s considering making an appointment.

“If over-the-counter antihistamines aren’t working for you, it’s time to see your physician,” says Ellis. Your doctor can prescribe better antihistamines, nasal steroids, eye drops and, if necessary, refer you to an allergist who can determine if you’re a candidate for immunotherapy. This can involve sublingual tablets or a series of allergy shots that slowly minimize your body’s reaction to the allergen so you don’t experience as many symptoms, says Ellis. “The most important thing is not to suffer in silence.”

Next, read about 11 solutions for seasonal allergies.

In one version of his 1996 song “Frybread,” Ojibwe folk-rock artist Keith Secola sang: “You can’t do much with sugar, flour, lard and salt. But you can add one fundamental ingredient: love.”

Since its creation in the 1800s, the subject of Secola’s song, frybread, has become a culturally significant comfort food within Indigenous communities across Canada and the United States.

Frybread has appeared in Indigenous films and pop culture for decades. In Smoke Signals, a 1998 indie drama written by novelist Sherman Alexie, a descendant of the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene tribes, one character wears a shirt with a Superman-style crest bearing the words “Frybread Power.”

The taste, colour and size of these fried dough discs differs across the continent, with each family and community adding their own touch. Ben Jacobs, Osage co-owner of Tocabe, a restaurant in Denver, Colorado that sells frybread and other Indigenous–inspired dishes, told The New York Times, “We’re never going to be your mom’s or your auntie’s frybread.”

Despite the variety, most versions have a few things in common. The basic ingredients are flour, baking powder or baking soda, and salt, which are whisked together and then kneaded into a dough ball using water or milk. (Other versions use buttermilk; some frybread makers swear it makes for a tastier bread.) After letting it rise, the ball is split into pieces and rolled into discs, with a few holes to help the bread stay flat as it’s fried in lard, shortening or vegetable oil until bubbly, golden and crispy.

Frybread can be enjoyed plain or with honey, butter, jam or powdered sugar on top. For a more filling version, add lettuce, ground beef, diced tomatoes, beans and shredded cheese to make a frybread taco, often eaten at festivals, fairs, powwows and other community gatherings.

Where does frybread come from?

As widely loved as frybread is, the calorie-laden treat—one plain piece clocks in at 500 calories and 20 grams of fat—is also a painful symbol of survival, borne out of the forced colonial displacement of Indigenous peoples across the continent.

One origin story says the bread was first made by the Diné (Navajo). In 1864, the Diné were forced to leave their traditional homeland in eastern Arizona and western New Mexico and walk the nearly 500-kilometre journey, known as the Long Walk, from Fort Defiance to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. Hundreds died of starvation along the way.

Among the cheap ingredients given to them by the U.S. government as commodity rations were wheat flour, previously unknown to them, and lard. As the legend goes, the Diné fried the often-spoiled flour to kill off parasites. The term “bannock,” which comes from the Gaelic bannach, meaning “morsel,” is often used synonymously with frybread. But while similar, bannock is typically denser than frybread, as it is usually unleavened. Bannock is made in Mi’kmaq, Inuit and Ojibwe communities, but was first brought to this land by Scottish settlers and fur traders in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Today, a burgeoning food-sovereignty movement aims to revitalize traditional diets, which don’t include frybread or bannock. “There is no oral tradition to be taught about frybread,” wrote historian Devon A. Mihesuah, a professor at the University of Kansas and enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation, in the journal Native American and Indigenous Studies.

As an enduring food, frybread stands as a testament to the resilience of Indigenous communities in the face of displacement and colonization.

Next, check out these 10 Indigenous authors you should be reading.

Holding a flashlight between her teeth, Sharine “Spanner” Milne adjusts the shock of a Harley Davidson Sportster at the motorcycle repair shop she owns in Townsville, Queensland, in northeastern Australia. Her fingers—long nails painted in flaming orange—work the pocket-sized wrench near the bike’s brakes.

Over the past three years, the 46-year-old mechanic, and owner of R.H.D. Classic Supplies & Services, has made several modifications to this bike, which belongs to a customer named Stewart, a 72-year-old orchid farmer. Stewart’s right leg was amputated so he wears a prosthetic, and he recently broke his left ankle. To make the motorcycle work for him, Milne adjusted the seat and handlebars to help with his back pain and, most recently, installed an electronic gear shift for him to use while his ankle heals. Giving up riding was never an option for Stewart.

“I’d hate someone telling me I can’t ride,” says Milne, who knows firsthand what it’s like to overcome a “life injury”—the term she prefers to use instead of disability. Milne was born with bilateral dislocated hips. Doctors told her she wouldn’t be able to have children and that by the time she was 40, she would no longer be able to walk without assistance. She proved them wrong on both accounts.

“I didn’t let it stop me,” says Milne, an Indigenous woman and mother to a grown daughter. Today, not only does she walk, but she also rides motorcycles and has amassed a large collection of bikes over the years.

Twenty-one years ago, as a single mother juggling three jobs in hospitality and hardly seeing her five-year-old daughter, Milne decided to return to school and enrolled in a pre-vocational automotive course. But as a woman aiming to become a motorcycle technician, she faced a lot of doubters. “I got laughed out of five shops,” she says.

Eventually Milne landed at R.H.D. Classic, first as a student, then as an apprentice and eventually taking over ownership of the shop in 2012. Kirsty, her former boss’s daughter, who is deaf and uses a wheelchair, gave her the nickname, “Spanner girl.” One of Milne’s first modifications involved setting up a sidecar for Kirsty so she could ride with her dad.

Today Milne runs a thriving business, but the injury-related modifications are her passion. Her projects range from crafting wheelchair-accessible motorcycles to converting her own sidecar into a type of hearse with a flatbed to carry her veteran customers’ caskets after they die. “The greatest respect I can pay them is to be able to take them to their final resting place,” she says.

By letting people continue to do what they love, Milne has helped them find emotional healing. David McHenry, a 55-year-old retired veteran of the Australian Defence Force with spine, hip and knee injuries from 35 years of service, turned to Milne to help ease the pain of riding for longer stretches.

“Spanner provides a safe space for veterans like me to come to when they are struggling. No judging, just comfortable conversation and some hands-on work to distract us,” says McHenry.

Along with his physical injuries, McHenry has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and his psychologist, who recommends riding as “throttle therapy,” can tell if he hasn’t been out on his motorcycle enough.

On the open road, Milne too finds a therapeutic rhythm. Some days the ride is her emotional outlet, but it’s also a way to connect with others. “On a motorcycle, I don’t feel like life’s passing me by. I’m part of it.”

Next, read about some unique ways people are giving back around the world.

The harsh winter weather brings with it the cozy allure of indoor activities, that unfortunately also create the ideal setting for colds and flu to spread. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not the frosty temperatures that cause the sniffles, but spending time in spaces with doors and windows shut, enabling respiratory illnesses to pass more easily from person to person. Plus, kids are getting exposed to a variety of germs and viruses at school and bringing them home! But with the right remedies, families can support their immunity through the winter season.

For over 35 years, Canadian company St. Francis Herb Farm has been researching, sourcing and growing organic herbs, extracting their health-promoting and healing properties to create natural medicine. Their herbal products have the power to help reduce the occurrence of, and ease cold and flu symptoms—and they’re 100 percent natural.

From daily immune support to cough relief, St. Francis Herb Farm’s line of kid-safe herbal medicines has a formula that caters to every need, and yes, they have adult formulas too!

Before Sickness Sets In:

Deep Immune® Kids is a mild-tasting children’s version of St. Francis Herb Farm’s award-winning Deep Immune® Original formula. This tincture helps support a healthy immune system to protect against common viral infections, colds and the flu. It’s formulated using two powerful, adaptogenic herbs— astragalus (helps maintain a healthy immune system) and codonopsis (helps relieve symptoms of stress such as mental fatigue). Kids can take it daily—before any cold and flu symptoms even begin—to support their immune system and ward off illness. The adult version is available in both a liquid formula and convenient capsule.

Chronic Cough Control:

Ease child’s coughs naturally with Elderberry Cough Syrup Kids. This syrup is formulated just for kids and features elderberry, a traditional herbal remedy rich in flavonoid compounds that helps relieve coughs, soothe sore throats, ease lung irritation, and clear mucus buildup in the upper respiratory tract. Sweetened with a touch of honey and formulated with wild cherry bark, this great tasting formula will help your kids breathe easy.

When You Can’t Shake a Cold or Flu:

Lessen the severity of your little one’s cold or flu and shorten its duration with St. Francis Herb Farm’s Echinacea Plus Kids. This product is formulated with anise, which is similar in flavour to fennel and licorice for a kid-friendly taste. Have a child who prefers a sweeter taste? Try Echinacea Plus Kids with Elderberry. Similar to the original version, it fights against common viruses, colds and the flu—but this version is alcohol-free and contains elderberry juice, giving it a sweeter taste.

To Stay Healthy Year-Round:

While we need vitamin D year-round, we tend to need it a little more during the dark and gloomy days of winter. St. Francis Herb Farm’s Vitamin D3 Kids is an easy-to-use and highly absorbable liquid drop format to help maintain healthy bones and teeth. It’s formulated with superstar ingredients like coconut oil and rosemary extract, which enhance absorption for the whole family.

For even more products for kids (and adults!) that can help soothe other cold and flu symptoms and even ease anxious feelings, visit stfrancisherbfarm.com.

My lunch pal, Pierre Trudeau

My father always worried that I would be the one child out of five who would have trouble “making it,” and not just because I was gay or a rabble-rouser at university. He thought I wore my heart on my sleeve and cared too much.

Perhaps he finally thought I would make it after all when, in 1994, I told him I was going to have lunch with the person he admired most, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. And not just anywhere but at the Ritz-Carlton in Montreal.

I was going to figure out a way to make Trudeau pay for it, too. After all, our slogan at university was “Make the rich pay.” Long before Justin Trudeau became Canada’s 23rd prime minister in 2015, there was his father, the charismatic 15th prime minister, from 1968 to 1979 and 1980 to 1984.

The elder Trudeau introduced an omnibus bill that allowed abortion under certain conditions, decriminalized the sale of contraceptives, tightened gun laws and decriminalized homosexual acts performed in private. Although I demonstrated against some of Trudeau’s other policies—in a civil society, you discuss and debate your points of departure—I had long admired his intelligence, vision and quick wit.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau put Canada on the world stage. On my trips to Lebanon or China or even Albania, when I would say I was from Canada, everyone would smile and say “Trudeau.” Yes, that one. The sexy prime minister who drove people wild and inspired Trudeaumania. The one whose attempt to create a just society put him on United States president Richard Nixon’s bad side.

Trudeau was incredibly fun to watch, like the time a photographer snapped him at Buckingham Palace at the G7 Summit in 1977 while doing an impromptu pirouette behind the Queen’s back. England had Thatcher, the U.S. had Nixon and we had Trudeau. The contrast could not have been more pronounced.

I met him in 1994 at the video release of Memoirs, based on his book of the same title. We spoke briefly, and I told him I was coming to Montreal. (I wasn’t, but of course I would if he would meet me! Besides, I am a Montreal Canadiens fan and happily made the pilgrimage to the old Forum almost monthly during hockey season.)

I later followed up with a letter asking if he would meet me for lunch at the Ritz to discuss his memoir, although I mainly just wanted to tell him in person how much his famous statement about the state having no place in the bedrooms of the nation had meant to me.

I called on my friend, the politician Marcel Prud’homme, for help giving Trudeau another couple of letters from me asking to meet for lunch. Eventually, Trudeau agreed. But when we finally met at the Ritz-Carlton, he told me he was not in the mood for an interview. “Let’s just have lunch,” he said, and suddenly I was the one in the hot seat.

I jokingly asked whether the government had a file on me, considering I had run against him for Parliament as a Marxist in 1980. “Well, I’m sure they must have,” Trudeau replied. “There must be a few files on you and me here and there.”

He had me turn off my tape recorder and wanted to know everything about that time in my life. It was almost as if I were looking for absolution when I told him I received a full year’s credit in my political science class for my attempt to topple him.

“Yes, those university days,” he said. “Even some conservative politicians will tell you they were leftists or Marxists back then.”

He also asked about my charitable work, especially in the areas of HIV/ AIDS, and gay rights in Canada and the Middle East. He talked about hitchhiking through areas of Jordan I had not seen at the time. After that, we had lunch a few more times, though ours wasn’t the kind of relationship where I could phone him up and say, “Hey, Pierre, what are you doing this weekend? How about a canoe trip?” (Maybe because I couldn’t paddle or swim.)

At one lunch, I congratulated Trudeau on his appointment, back in 1984, of Canada’s first female governor general, Jeanne Sauvé. What a novel idea—an actual woman representing a female monarch!

“I adore her,” I said. “Hey, the next time you need to appoint a gay Arab, I’m available!”

“I’ll make a note of it,” Trudeau said dryly. “But you don’t strike me as the type to get up at six in the morning and fly out to open a school or community centre in northern Saskatchewan.” Great powers of observation, that one.

“Would I have to believe in the monarchy or in a higher power to be governor general?” I asked.

“Well, not believing in the monarchy, I think you can get away with that,” he said. “But I’m not sure I can sell the idea of an atheist governor general.”

“But imagine all the art I could put on the walls at Rideau Hall!” (Years later, when Adrienne Clarkson took the position, I donated a couple of paintings by Attila Richard Lukács.)

I met with Pierre Trudeau enough times that when I went back to the Ritz a few years ago, long after he had died in 2000, the maître d’hôtel recognized me—perhaps from my brooch, which identifies me better than a passport.

“Would you like to sit at the same table where you used to sit with Monsieur Trudeau?” he asked.

I would. I did. It was a booth in the back where you can survey the whole room, but no one can truly see you.

(Next: Check out this 2018 interview with Margaret Trudeau, about her book The Time of Your Life.)

Cooking for Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Fitzgerald would make me scrambled eggs in her kitchen—or I’d bring something over and we’d eat it in her backyard garden— but I think if I had known just how revered she was, I might not have been so relaxed around her.

Ella performed from the 1930s all the way through the ’80s, and she would come out on stage in an ordinary dress, too long or large on her, and wearing glasses so thick you feared she’d trip before she got to the microphone. Then she’d begin to sing, and her voice would take over and fill the room alongside the sounds of a full orchestra.

Duke Ellington once remarked that he had never seen musicians line up to hear a singer like they did for Ella. She had perfect pitch and a reputation for never doing a song the same way twice—except, of course, in the studio.

Frank Sinatra called her “the greatest popular singer in the world, male or female, bar none.” He also said she was the only singer with whom he was nervous performing, because he kept trying to reach her heights.

I met Ella, who was 40 years my senior, in 1978 through a mutual acquaintance, the publicist who managed Tony Bennett for 12 years and also helped manage Ella in Canada. He booked her into the Imperial Room, a 500-seat Toronto venue for big-name performers like Bennett, Louis Armstrong and Tina Turner. (Bob Dylan was infamously refused entry for not wearing a tie.)

“My uncle saw you perform in Baalbek in 1971,” I told Ella backstage. The Baalbek International Festival in Lebanon—with its dramatic backdrop courtesy of the Temple of Bacchus Roman ruins—is an experience no one forgets.

“You’re Lebanese?” she asked me. “Tell me, where can I find good kibbe in Toronto?”

That was easy: My mother’s kitchen. Kibbe is one of the national dishes of Lebanon and Syria. It’s made of meat and bulgur, baked or fried, with finely chopped onions and pine nuts.

Ella wanted kibbe? She would get it, and more. I asked my mother to make her some, and Mom went all out—not just kibbe but side dishes to go with it.

I saw to it that she used the finest ingredients in everything she made for Ella—better even than she would buy for our family. The fresh fruits and vegetables came from her garden, of course, but I searched specialty stores for the best cuts of beef, organic this and that, and then sat in the parking lot peeling the price stickers off my purchases. My mother never would have paid even half of what I spent on those pine nuts.

I brought Ella that food most nights while she was in town, which was up until 1986. If she was doing a two-week run, I showed up at her room at the Royal York Hotel with a different Lebanese dish on seven or eight of those nights. She didn’t like to eat right before a performance, but she needed to have a light meal, as she was diabetic. I have type 2 diabetes, too, so I knew that routine only too well.

It’s funny to reflect on it now. I was bringing kibbe to Ella Fitzgerald the way others might bring a photo for the star to sign. I didn’t always stay for the show—sometimes I went off to play hockey—but I managed to bring my parents on several occasions to see her perform.

Sometimes Ella would come over to my nearby apartment and just hang out after one of her performances. There was a privacy to it for her, I think, a feeling of relaxing rather than having to hold court at her hotel. She would sit around our table with a few friends and I would, naturally, serve a Lebanese dinner.

We’d have music blasting, sometimes Joni Mitchell’s albums Clouds and Blue, and sometimes I even played some of Ella’s old music. “I sounded good back then!” she would say with a laugh.

She repaid the hospitality by cooking for me at her grand, lovely home in Beverly Hills. She had a warm, joking relationship with her housekeeper; Ella credited laughter with getting her through so much in her life.

I loved her self-deprecating sense of humour. Once, when a reporter asked her what it felt like to be considered the greatest singer in the world, she responded: “Honey, you should go ask Sarah Vaughan.”

At her home, she would barbecue for us, with honey-drizzled fruit salad for dessert—but she always checked the glycemic index of everything she served, for her sake and mine.

I named my first dog, a Tibetan terrier, Ella. The dog went with me everywhere. My dogs have always mirrored my health issues; Ella the dog had kidney failure when I had kidney failure. “I do hope that dog learns how to sing,” Ella said when she learned of the four-footed Ella in my life.

I stayed in touch with the real Ella over the years as her diabetes took its toll, and last saw her in 1991 in Los Angeles. But she was always more concerned, in the best motherly way, with my own sugar levels. Late in life, she had both legs amputated due to diabetic complications and began refusing to see old friends.

I called to see how she was, and in her selfless manner, she asked if I was keeping my sugar under control. “You know, if you get the best wines and scotch, all you really need is one glass,” she said. “And keep away from the baklava!”

I could never figure out my fierce attraction to Ella. A friend asked whether I was like a son to her, but I don’t think so. I loved to hear her sing, of course, but it was more than that. She made everyone feel special and equal. There was none of the glamour and the trappings one might expect with the First Lady of Song.

(Read about secret signs of type 2 diabetes you might be missing.)

Marlon Brando in my mom’s backyard

“What can I get you?” my mother asked Marlon Brando. She wasn’t exactly sure who he was, other than some kind of actor, a new friend I had brought over for a backyard barbecue.

She would have asked the same question of anyone. In our family and in our Lebanese culture, one of the ways we show love is with food. A lot of it. Lots of love, lots of food. It wouldn’t have mattered if my mother had known who Marlon was, because she treated everyone with the same courtesy and hospitality—and anyway, to my mom, her kids were the stars.

Whether I brought over Ginger Rogers, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Elizabeth Taylor or any of the celebrities I befriended over the years, to her I was always the main attraction. The only time I shared the spotlight was when one of my siblings or their kids were also on hand.

My mother didn’t bring out the good china for Brando; she never used her good china for anyone. She had it there on display in the dining room buffet, one of those grand wooden pieces crafted in the old style.

It was 1989, and Marlon sat near the picnic table in my parents’ backyard, on one of our folding lawn chairs, that ’70s-style metal tubular variety with a fabric-strip seat.

There were vegetables growing on one side of the yard to disguise the chain-link fence that separated our house from our neighbour’s. Our vegetables were heavy on tomatoes, Lebanese cucumber and kousa—similar to zucchini and also known as Lebanese squash. There was also plenty of marjoram, sumac and the summer savories one can eat green or add to salads, and which, when dried, go into za’atar, a Lebanese spice blend that is suddenly all the rage everywhere but has been here all along.

Our family home was a three-bedroom house with a carport. It was located behind a strip mall on a dead-end street in Rexdale, a working-class neighbourhood in north Toronto. At the end of the street was the Humber River, where my two sisters, two brothers and I had played out our Tom Sawyer adventures. There was a big shed out back where Dad kept his tools.

My father was pouring a glass of arak for the man from On the Waterfront. “Did you know that your name is English for the Lebanese name Maroun?” he asked Marlon.

“St. Maroun, yes! I love that,” exclaimed Marlon, to everyone’s amazement. “The patron saint of the Maronite Church.”

Many Lebanese are Maronites. It was not the first time Marlon surprised me by coming out with something obscure, but he was a sponge for information that intrigued him. And virtually everything intrigued him.

“We’re not Maronites, we’re Greek Orthodox,” my father clarified to the Godfather over tabouli and fattoush salads.

“We’re not here to talk religion,” I interceded, heading that off.

I don’t think my parents would have acted any differently had they known their guest was one of the most revered actors of all time, a two-time Oscar winner. Not that I put much stock in awards. Who’s to say who is “the best” of anything?

We were all instantly in love with Marlon anyway. He put everyone at ease and tasted everything Mom made, complimenting her lavishly. A couple of times he asked, in French, for the names of certain foods in Arabic.

It seemed that Brando was up for just about any conversation, no topic off limits, but I purposely steered the talk away from his fame and acting career. It’s all on screen anyway, and I figured he’d enjoy a break from the endless questions—what was it like doing this or that or with this one or that one. I had no need to ferret out any of his secrets.