Broccoli and cauliflower

If you like broccoli or cauliflower, consider starting these vegetables inside. The Clemson Cooperative Extension notes these two vegetables are easy to transplant, so when the time comes to move them outside, they’ll be hearty enough to survive cooler soil temperatures.

Tomatoes

Tomatoes are a favourite among gardeners, and there is such a wide variety to choose from. The University of California Master Gardener Program notes tomatoes are a good choice for starting inside because they can be transplanted with few complications. (Don’t have a green thumb? These hacks can revive almost any dead plant.)

Lettuces

Salad lovers rejoice! Texas A&M AgriLife says lettuces are a good option for transplanting because this crop can tolerate cooler soils, thus will continue to sprout even if the soil outside is cool during the late weeks of spring.

Peppers

There are some vegetables that thrive in hot weather, and peppers—both sweet and hot—fall into that category. If you’re looking to grow peppers and don’t want to wait until late in the summer to enjoy them, start them inside. The National Gardening Association notes frost can damage pepper plants, so to combat this, get them started inside and wait until all danger of frost has passed before transplanting. (First-timer grower? Try these 10 simple tips for growing a vegetable garden—anywhere!)

Beets

If you have access to fluorescent lights, the University of Maryland Extension suggests starting beets indoors. Beets are a good choice because as a root vegetable, they transplant well. The extension notes other good options for growing indoors with the help of fluorescent lights are kale, onions, leeks and beans.

Celery

The National Gardening Association says celery can be a challenging plant since it has such a long growing period—130 to 140 days of mostly cool weather. The association says it’s best to start celery seeds indoors 10- to 12 weeks before the last frost. When the seedlings reach four- to six-in. high, they can be transplanted to the garden a week or two before the last frost date. (Learn about the low-light plants that thrive in near darkness.)

Cabbage

Cabbage, a cool-weather-loving vegetable, benefits from a longer growing season, so start it inside four to six weeks before transplanting. Seed Savers Exchange says you can then transplant the cabbage seedlings outdoors, just before the last frost.

Cucumbers

While cucumbers (shown above) don’t like to have their roots distributed, which can make them tricky to transplant, Burpee notes it’s worth the risk to start a few cucumber plants inside if this is one of your favourite garden vegetables. Whether you’re growing them for salads or for pickling, start cucumber seeds inside about three weeks before setting them outdoors. Just make sure the outdoor soil temperature is at least 60 degrees and all danger of frost has passed. (Don’t miss the 13 things you should know before starting a garden.)

Eggplant

Because eggplant has such a long growing season, Seed Savers Exchange says it’s a vegetable that does well when started indoors. The company says it’s best to sow eggplant indoors seven to 10 weeks before transplanting outside, then transplant outside four to six weeks after the last frost, into a warm and sunny location. Make sure outdoor soil temperatures are at least 13 C before transplanting outside.

Corn

While you shouldn’t be in a rush to plant sweet corn in the garden, you can get a jump-start on the season by starting the seeds indoors. The National Gardening Association says you can start corn plants indoors in pots. When the seedlings are a few inches tall, transplant them to your designated garden spot.

Next, save time and money by trying these gardening shortcuts.

When I was first diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer in 2015, one of my biggest fears—aside from the obvious one of dying—was that there were so many books I would miss out on reading to my three young girls. When you have a terminal illness, there is a lot of talk about leaving a legacy. Some people write letters to their children. Some record videos. The only legacy that felt right for me to leave was a literary one: a shared love of books that we have read together.

With a disease like mine, you never know how things are going to go. I enjoyed two years of relative stability before the cancer spread again. It has always been in my ribs and back, but now it has reached my hips, legs, uterus and possibly other places; at this point, it is hard to keep up. I can break ribs when I sneeze, or if I sleep in the wrong position—both things that have actually happened. For all of last year, I walked with a cane and needed a wheelchair for any distance further than up the stairs to my bed.

In my mind, I am still a young woman. But at 44, my body feels so much older—and the thought of leaving behind my husband and my three children, ages 12, 10 and seven, is terrifying. I want to make every moment, even moments spent reading, count.

The first book

I was already a huge fan of the Harry Potter series when I was diagnosed, so that was at the top of my list. These books got me through a dark time in my 20s and hold a special place in my heart. During the winter of my diagnosis, while I was going through chemotherapy for the first time, I started my oldest, who was turning eight, on her Harry Potter journey. My other daughters were then five and two, so they were too young to start just yet. I kept thinking, Just let me live long enough to read all the books to my girls.

From there, I made a list of other books I wanted us to share. Reading together has always been our thing. I was never a mom who wanted to get on the floor and play; I was always more interested in sitting us down and reading. My girls knew that I would usually drop everything if they asked me to read to them. I remember asking my oldest daughter years ago if she would still let me read to her even when she was reading chapter books on her own. She is in Grade 7 now. And yes, I still read aloud to her when I get the chance.

Anne of Green Gables was second on my list. I tend to gravitate toward the classics, and reading the entire Anne series is such an enjoyable way to learn about growing up as a smart, determined girl.

The Little House on the Prairie series came next, even though I hadn’t read it as a kid. I have since read the entire series through at least five times to my daughters. While there are definitely parts of the books that are worth criticizing today—like their portrayal of Indigenous peoples—I like the discussions they create in our family. For a while, a lot of conversations in our house would start with: “What would Ma or Pa Ingalls do?”

Other books on my list have included A Little Princess, A Wrinkle in Time, The Secret Garden, The Dark Is Rising series, Little Women, Pride and Prejudice and Jane Eyre. I have now read most of these to at least one of my daughters. Many more new-to-me and modern books have been added to the list, too. The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman and The Swallow by Charis Cotter sparked discussions about ghosts and death. One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia taught us about the civil rights movement in 1968 Oakland, California. There is more diversity in these modern books, so while I like the classics, I try to not limit myself to them. We are all learning together.

My 12-year-old and I are currently working through a number of historical mystery series: the Maisie Dobbs books by Jacqueline Winspear and the Lane Winslow mysteries by Iona Whishaw. These two series feature strong, smart women who made it through two world wars and now solve mysteries. It’s fun having someone in the family who enjoys these more mature books. I’m glad I have lived long enough to move away from children’s books and that I am still here to expand our literary experiences.

The list grows

As the girls get older, the list of things I want to share with them has changed to include music and movies. Each child is so different that what they want me to share and what makes sense to share with them is different, too. My youngest is the one who would not have remembered me had I died when first diagnosed. She’s now seven-and-a-half. To her, I have passed down my love of musicals. She can spend the day complaining that the kids in her class are too loud—even with her noise-cancelling headphones—then come home and turn Hamilton on at full volume in her bedroom.

“Mom, when you are a grandma, will you teach my kids about Harry Potter?” my middle girl recently asked me. I didn’t really answer. I said I would like to, but I know she understands on some level that the chances of me being around then are pretty slim, and I refuse to lie. I wish I could say yes and know that I will meet these imagined grandchildren someday, but I can’t. It’s hard. I’m grateful that they all share my love of Harry Potter and even more grateful that, this summer, I finished reading the last book to my youngest daughter. Some days, I didn’t think I would be around long enough to achieve this goal. Doing so felt momentous.

You think when you have children that you have all this time with them, but it isn’t necessarily true. My fear is that all they are going to remember about me is how my illness coloured their childhood with the looming threat of death. They have all but resigned themselves to the fact that I’m not much fun. Some days all I can do is get out of bed and feed them lunch, while other mothers are out attending Terry Fox runs and volunteering at the school.

But books are something I know, and reading is something we can do together; even on my worst days, we can snuggle up and read something. As Sirius Black says in the film version of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban: “The ones who love us never really leave us. You can always find them, in here.” Sirius points to Harry’s heart when he is saying this, but I believe that the ones who love us can also be found in the pages of a book long after they are gone. At least that is what I hope for my girls.

Read about how this Ontario doctor helps breast cancer patients prepare for treatment.

© 2019, Melanie Masterson. From “Leaving a literary legacy: In wake of my cancer diagnosis, I decided to read to my daughters,” from This Magazine (December 2019), this.org

Shawna Dias’s sewing machine is barely visible on her work table behind racks of fur. Hot pink, bright yellow, baby blue, the furs hang like a fluffy rainbow. In the space of about a day, she can transform them into custom-made parkas at her Rankin Inlet home. “When I first started, I didn’t think it was going to be a business type of thing. I didn’t realize they were going to get so popular,” she says. To be fair, Dias was 12 when she first learned to sew coats, watching her mother stitch. Today, she’s one of the most popular parka makers in the Kivalliq, (the southwestern part of Nunavut), with a lively Facebook page, Dias Designs, and a waiting list in the triple digits for custom orders.

She’s not sure how many coats she sews in a year, but her niece counted the parkas on her Facebook page, and says she made around 200 in six months. They don’t all stay in Nunavut either, where custom-made parkas are common. She takes orders from all over Canada and even the United States. Dias creates her own patterns, based on people’s measurements or, if they’re local, their body shape.

“Everyone’s got a different body shape, so it’s so much easier freehand cutting out a coat for somebody,” she says. “It’s what we grew up with, so it’s just what we use. Well, that’s what I have used because of how my mother used to make them. She was born in 1929, and began sewing when she was young, too. So, old patterns!”

Parkas have existed for centuries. And now the world is learning what northerners have always known: if you want to stay warm, there’s nothing better than a northern parka.

Hot history

The Kitikmeot Heritage Society features rows of parkas, standing like sentinels through time. Its Patterns of Change exhibit includes examples of Inuinnait parkas from over 150 years, made by dozens of different community members. Pamela Gross, executive director of the Kitikmeot Heritage Society, says, “The exhibit celebrates how ingenious our people were to create garments that were very beautiful, finely made and resourceful.” Displayed parkas include traditional styles made from caribou, the Mother Hubbard style with ruffled hem and cuffs, and modern coats featuring brightly dyed seal skin that are, as Gross says, “traditional with a twist.”

Those garments are written over with history, Gross says, with changes expressing major events in the lives of northern peoples—not all of them good, but each influencing the living culture and what people wore. First contact with Europeans, for example, brought new materials such as calico and wool to the Arctic. Parkas changed in both shape and style through the Cold War’s Distant Early Warning Line era, when military styles and fabrics arrived. And many parka makers from different parts of the North exchanged techniques when they were forced to attend residential schools, swapping tips on floral embroidery styles and other regional techniques.

Gross says determining the origins of each stylistic change was a project in itself. It’s hard to pin down, even today, exactly why individual parka styles are preferred in each region of the North. Some of it has to do with what people are doing while wearing the parkas, some of it has to do with traditional patterns, but a lot of it comes down to the styles and preferences of the individual seamstresses.

Details of the parkas—like whether the sleeves are curved or straight, the length of the garment and how fitted it is—often come down to preference and trend. For instance, many of the men’s parkas Dias makes are shorter, with elastic at the wrists and hem. In the Baffin region, they tend to be longer. She’s not quite sure why, whether it’s just the fashion or if the style is dictated by the specific activity (for instance, hunting parkas are generally pullovers, because zippers may freeze to the wearer). She, like many seamstresses, adapts to what her customers need.

“That’s why it’s so hard to explain the different shapes of the coats or how they’re sewn,” says Dias. She tends to favour fitted parkas herself, with delicate lines and vibrant materials. You can spot one of her creations by the lace she incorporates into her designs. “My mother never used to use stuff like that.”

Cultural comeback

One territory over, tucked away in the underbelly of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife, NWT are even more parkas, some snuggled in the freezer to protect their fur. Karen Wright-Fraser flips over the hem of one to show the underside of the embroidered trim, where the tiny stitches that went into creating this example of Delta Braid, a type of ribbon trim from the Beaufort Delta region made from layers of bias tape and seam bindings in geometric patterns, are barely visible. Wright-Fraser is the former community liaison coordinator at the museum and also a seamstress. “The techniques were pretty much forgotten,” she says.

That’s now changing. Over the past several years, she’s seen an upswing of people learning the skills of their grandmothers, particularly as parkas become a popular fashion item on social media. “A lot of young people weren’t interested before. Now I notice a lot of them are going to their grannies and learning,” she says. They have pride. Even more are learning online and going to online groups for support and help. “There are so many different ways. Then you choose the way that works for you. You’re finding your own path.”

She pulls out another coat, this one a vibrant red with shiny, smooth embroidered flowers. “Isn’t it beautiful? That’s skill. It looks like it was done on a machine, but it’s by hand,” she says, pointing out the middle of each flower, decorated with dozens of French knots, made from embroidery floss. “People learned this from the nuns. Before that, we used to use moose hair and seed beads. People would use porcupine quills to sew geometric designs. Then the floral things came from the nuns.”

That’s what distinguishes many Dene or Gwich’in parkas: the beautiful embroidery dancing across the hems, the yokes and the cuffs. Many examples came out of the Inuvik Sewing Centre, which from the 1960s to the 1980s brought Indigenous women together in a co-operative to produce parkas for commercial sale. Such parkas often feature intricate Delta Braid and appliquéd fabric figures. Those coats can still be spotted today, with their signature Inuvik tag stitched into the collar. Even more exquisite work can be seen on Spence Bay parkas, produced by women in what is now Taloyoak, Nunavut.

No matter the style, the time dedicated to making something useful and beautiful is a way to show respect and mark your family as good providers. Even today, when people have nine-to-five jobs and free time is scarce, wearing a handmade item carries a different value than just buying it from a store. “There’s more to it than just walking around with a beautiful parka,” says Wright-Fraser. “It was made with absolute love.”

Science of survival

In fact, parkas may have been what kept our species alive. Mark Collard, a professor at Simon Fraser University, proposes that Neanderthals died out because they didn’t have specialized cold-weather clothing. He and his grad students studied the bones of animals left behind at ancient sites inhabited by both early modern humans and Neanderthals and concluded that such animals as rabbits, foxes, wolves and wolverines were likely used as a source of fur, rather than food, for early modern humans. Bone needles and other evidence at the sites also suggest early modern humans were tanning hides and creating fitted cold-weather garments, while Neanderthals were donning, at best, simple cape-like garments.

It helps explain why even though other studies have found that the bodies of early modern humans seemed to have been adapted more for tropical conditions, they still outlived Neanderthals—whose stout bodies and short limbs evolved for more glacial conditions. In addition to protecting from frostbite and hypothermia, parkas would have allowed for a greater range of hunting and gathering and longer stays on the land, which would have increased the chances of not just survival, but the opportunity to thrive.

And while parka materials may have changed over time, the science of keeping warm has not. “The traditional clothing system developed and used by the Inuit is the most effective cold-weather clothing developed to date,” concluded a 2004 study published in Climate Research on the effect of Inuit fur parka ruffs on facial heat transfer. The study placed sunburst-style parka hoods into a wind tunnel to see what happens under extreme temperatures. In the wind, friction forms a collision of molecules next to the skin called the boundary layer. This layer insulates the skin. The study found that natural fur creates a thicker boundary layer by changing how air flows across the face. Of all the designs, the sunburst style proved one of the most effective.

Natural fur has hairs in a variety of lengths, changing how the air flows and protecting you even more. The most effective fur for this, according to the study? Wolverine, which surprises no one making parkas. Wolverine, which easily sheds ice and frost, has long been used to trim hoods in the North, alongside wolf, fox and other animals. “It’s so much warmer! I had a fake fur coat once. You’ll just freeze your face with that,” says Dias.

As frequently as you’ll see custom-made parkas in the North, the streets of Yellowknife, Whitehorse and Iqaluit are also filled with the ubiquitous Canada Goose. But the company is paying attention to those traditional-inspired designs. In 2019, Canada Goose launched Project Atigi (the Inuktitut word for parka) with the first round of 14 seamstresses from four Inuit regions—Inuvialuit, Nunatsiavut, Nunavut and Nunavik—creating parkas using Canada Goose materials. Part two, launched in January 2020, showcases 90 parkas made by 18 designers, each commissioned to create a collection of five pieces. Proceeds from sales of each parka will go to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national organization protecting and advocating for the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada.

While some saw the move as appropriation of Inuit culture, others saw it as an opportunity for appreciation outside of the Arctic. Gross, for one, says it’s a good thing when southerners see the talents of northern seamstresses. “There are a lot of people who still think of us as ‘Eskimos,’ people who live out in iglus,” she says, adding, “This is something we can hopefully change through talking and sharing who we are through our culture. It’s something people should be proud of.”

© 2019, Jessica Davey-Quantick. From “Art and Science of Staying Warm,” Up Here (December 2019), uphere.ca

The cabin where it all started

Tla-o-qui-aht Elder Joe Martin slows his motorboat around an eastern fin of Meares Island into Cis-a-qis Bay. It’s taken 30 minutes to get here from Tofino, a popular surf town and tourist hub on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Clayoquot Sound, B.C. “Can you see it? Can you see the cabin?” Martin’s friend Leigh Hilbert asks, pointing out a silver speck in the distance.

Also on the boat are Joe’s daughter Gisele Maria Martin, an educator and Tribal Park guardian, responsible for the environmental, archaeology and stewardship monitoring of Meares Island, and us non-Indigenous guests: myself, Hilbert and Hilbert’s partner Oona. We coast on the glassy inlet, anticipation swelling with the rising tide. Then, I can see the hand-built wooden dwelling beneath a curtain of cedar boughs. Nailed to the siding is a small green stop sign with the words “Log for the Future—Stop Clearcuts.”

“Welcome home,” Hilbert says to himself.

The 1993 Clayoquot Sound blockade, known as the War in the Woods, gained international attention and set off a chain reaction of efforts to protect B.C.’s old-growth rainforests. But a decade before, a quieter resistance took root here on Wah-Nah-Jus Hilth-hoo-is (Meares Island). It’s not as well known as the Kennedy Lake Peace Camp, where nearly 900 people were arrested. And neither it nor the War in the Woods ended the clearcutting of old-growth forest. But the campaign to protect Meares Island is an inspiring early example of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people working together to defend the land.

It’s been 20 years since Hilbert has seen the 320-square-foot cabin that served as the de facto headquarters of Canada’s first logging blockade. That cabin is also where Martin and Hilbert cemented their bond. Over nearly five decades of friendship, nothing compares to the winter they helped save Meares Island from chainsaws.

Martin leads us inside the cabin, as he and Hilbert walk across the creaky floors and reminisce. A cupboard door broken off at the hinge is carved with a moon symbol. Gisele explains that sun and moon crests often represent iisaak, an important Indigenous law that is also a verb, meaning “to observe, appreciate and act accordingly.”

Martin, now 67 years old, and Hilbert, now 70, stop at a display of sepia photos, warped by time and water. Memories flood back. Of Martin’s late father, Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary Chief Robert Martin, who lived at Cis-a-qis for three months with his partner during the winter of 1984–1985. Of Hilbert doing media briefings via two-way radio. He shows us the wood stove that warmed those who joined the forest protection effort, sometimes 30 in this small space.

“There were sleeping bags side by side by side,” Hilbert says. “We were here for the entire winter. We were determined.” Gisele, who was only seven during the encampment, remembers lots of singing. “What in the world can we do? I’ll hug a tree, won’t you?” she starts performing, reciting the chorus to one of the tunes from “Songs for Meares Island,” which was eventually recorded and sold as a cassette tape to raise funds for the blockade. “There were people from all over who came here,” Gisele says. “That strength and unity was really warm.” And, as today’s movement to defend old-growth forests gains ground once again, there are many lessons to be learned from past efforts to preserve the forests and watersheds of Clayoquot Sound.

Saving Meares Island

Hilbert and Martin met in the mid-1970s working for MacMillan Bloedel, a multinational timber company that was once the largest private corporation in B.C. Hilbert moved from Seattle to Tofino in 1973 to take an engineering job designing logging roads and cutblocks, areas where forest is razed for timber, around Clayoquot Sound. While Martin rigged machinery to drag logs, Hilbert was usually surveying ahead of the road-building crew. He remembers, in the early days, passing one mammoth tree after the next as they penetrated deeper into the forest, ancient cedars and firs dropping behind him like bombs.

Hilbert knew how rare temperate rainforests were—the misty, carbon-rich coastal landscapes covered less than 1 per cent of the planet to begin with. Not only was it the age, but the sheer size of the trees floored him. He recalls coming across two enormous western red cedar trees near Whitepine Cove. When he wrapped his survey tape around the butt of the largest one, the tape read about seven metres in diameter. “I had never seen anything like it,” Hilbert says. “I thought, ‘We can’t be cutting this down.’”

That conviction led Hilbert to quit his job exactly a year after starting. But having had access to the company’s projected logging blueprints, he began alerting people like Martin about the forests’ planned future. In 1979, this knowledge helped spark the formation of the environmental group Friends of Clayoquot Sound. On the proposed chopping block: Meares Island, an 8,500-hectare land mass that was home to some of the province’s largest red cedars and about 350 Tla-o-qui-aht residents.

By 1981, opposition from Friends of Clayoquot Sound, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and their allies prompted the government to set up the 11-member Meares Island Planning Team. The Ministry of Forests tasked the group with creating an “integrated resource plan” that acknowledged the island’s non-timber values, such as Indigenous culture and recreation. But after more than three years and three proposals, the B.C. government instead accepted a counterproposal from MacMillan Bloedel and B.C. Forest Products to log 53 per cent of the island over 35 years.

And so a new idea sprouted: an encampment at Cis-a-qis (Heelboom) Bay. It was here that the Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht First Nations declared Meares Island an Indigenous protected area, or Tribal Park, in April 1984. According to MacMillan Bloedel’s blueprints, the bay would be the start of a new logging road into the heart of the island’s old growth. So Hilbert built a cedar-shake cabin, nestled between two living cedars, to monitor the entrance.

The thought of large-scale destruction on Meares Island— slated for $25 million worth of logging—galvanized a diverse cross-section of society to join the protection effort. Tofino doctors, lawyers, business owners and town councillors joined forces with First Nations leaders and nature-loving drifters. Money and legal aid started flowing in. So did supporters from Haida Gwaii and California, and media from all over the country. Nothing went ahead without the blessing of Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary Chiefs and Elders, as well as the elected Chief at the time, Moses Martin, Joe Martin’s uncle.

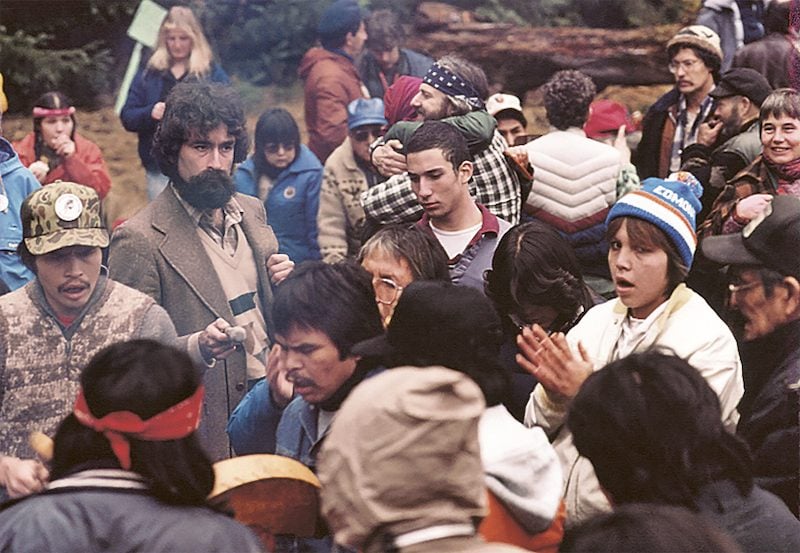

Moses, who’s now 79, played the central role in a historic standoff on November 21, 1984. Around 250 people were on the beach and in the water trying to block MacMillan Bloedel’s 40-foot crew boat from sailing in. When nine forest managers and three fallers armed with chainsaws arrived at the island declaring their right to the tree-farm license, Moses read his own declaration of Tla-o-qui-aht rights and title. Then, with a sweep of his arm, he invited the workers into the Tribal Park for a meal, but only if they left their chainsaws on the boat. The crew remained on its vessel.

Industry power

Forest defenders successfully warded off MacMillan Bloedel’s road building and tree harvesting all winter long. And on March 27, 1985, they celebrated their victory moment when the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled that no logging could take place on Meares Island until Indigenous land claims had been settled. It was the first court injunction preventing logging in the province’s history. It’s still in effect today. “The forest is still standing,” Martin says. “And I think it inspired people across the country to stand up for their rights.”

Several more logging blockades and court cases followed, leading up to the faceoff at the Kennedy River Bridge near the Ucluelet-Tofino junction in 1993. Nearly 900 people were arrested there, making it one of the largest acts of non-violent civil disobedience in Canadian history. Two years later, the Forest Practices Code became law under the NDP government, bringing in new regulations for cutblock size, road building and buffer zones for salmon habitat. The Forest Practices Board was created as a “watchdog” to ensure proper management of B.C. forests—95 per cent of which are on public land.

Some of those victories were more short-lived. An industry-led crusade to weaken regulations, followed by the shift to a Liberal government in 2001, significantly eroded the Forest Practices Code, which was soon replaced by the Forest and Range Practices Act. Oversight was outsourced to “qualified professionals” working for timber companies, effectively privatizing public forests. From 2004 on, conservation could only happen “without unduly reducing the supply of timber.”

In the name of global competition and better U.S. relations, the provincial Liberal Party leader at the time, Gordon Campbell, also scrapped two measures that supported local economies: a condition requiring companies to process logs in the region they were harvested and a program that would have provided funds to build a value-added timber industry. All of this opened the door to raw-log exports, the shipping of unprocessed logs to the highest bidder overseas, which doubled on the coast between 2000 and 2016. During the same period, 44 mills shut down and 32,000 forestry jobs were lost.

Today, a quarter of the annual harvest, or half of everything logged on Vancouver Island and the coast, is old growth. Red cedar—the most valuable tree species in a lumber market that’s been booming due to pandemic-inspired U.S. home renovations—is of particular importance to the logging industry. In September, it was selling for US$1,600 for a thousand board feet, which is almost double the price of spruce, pine and fir.

A study released last April found that of the 13.2 million hectares of remaining old growth in B.C., less than three per cent still contains the monumental trees that most people picture when they think of old-growth forests. Productive old forests are “effectively the white rhino,” the study states. “They are almost extinguished.”

Lessons for today

Growing awareness about how little old-growth forest is left has ignited a new push for protection. In 2016, the Union of B.C. Municipalities—representing more than 150 city, town and regional governments—passed a resolution calling for an end to old-growth logging on Vancouver Island. In 2018, more than 220 international scientists signed a letter urging the province to conserve its globally rare temperate rainforests for the sake of the planet. Several First Nations have rolled out conservation strategies focused on the old-growth red and yellow cedar trees so integral to their cultures.

On September 11, 2020, the NDP government released a much-anticipated review of old-growth forests in B.C. The independent report, titled “A New Future for Old Forests,” calls for a “paradigm shift” that prioritizes ecosystem health over the timber supply. Following the passage of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act in late 2019, the report lists Indigenous involvement as recommendation number one.

Coinciding with the release, former Forests Minister Doug Donaldson announced the deferral of old-growth logging within more than 350,000 hectares, as well as the protection of up to 1,500 giant trees. The total area of old growth in the protected space comprises about 1.5 per cent of B.C.’s mature forest and is roughly the same amount that’s currently harvested every year.

Many conservationists believe the move didn’t go far enough. They argue that Clayoquot Sound, which makes up nearly three quarters of the moratorium, was already less vulnerable because of Forest Stewardship Council certification and decades of resistance. The government’s announcement also didn’t cover the province’s most at-risk forests.

Despite these shortcomings, others are celebrating the news for Clayoquot Sound. Clayoquot—an anglicized version of Tla-o-qui-aht, which contains a root word meaning “moving and changing behaviours and emotions”— is a place where Indigenous leaders and allies have stood up time and again to protect their lands and waters, and the creatures and humans that rely on them. It’s a place where humans are a keystone species in those lands and waters. It’s home to cultures that teach the law of iisaak. Observe. Appreciate. Act accordingly.

Back on Meares Island, sunlight streams through cedar and hemlock branches, casting a tangle of berry bushes in a moss-green glow. Joe and Gisele stand outside the cabin where a group of individuals lived for a winter to protect the island’s forests. As the Martins pick huckleberries and talk about their ancestral connections to cedar and salmon, I get the sense that they’d do it all again.

Here’s what it’s like to photograph grizzlies in British Columbia’s Great Bear Rainforest.

© 2020, Serena Renner. From “The Deep Roots of BC’s Old Growth Defenders,” The Tyee (September 16, 2020), thetyee.ca