Learning how to play UNO is pretty much a childhood rite of passage. At some point growing up, your parents, babysitter, or camp counsellor probably taught you the rules: When it’s your turn, match a card in your hand with the top card on the discard pile by either number, colour, or word. Use your word cards strategically against your opponents, and don’t forget to yell “UNO!” before playing your next-to-last card.

But have you ever taken the time to actually read the UNO rules yourself? Facebook user LaToya McCaskill Stallings recently did and discovered that she’s been playing the card game wrong her whole life.

Chances are, so have you.

The little-known UNO rule

While you can use Draw 2, Reverse, Skip, and Wild at any time, it turns out your Wild Draw 4 can only be used when you legitimately can’t play another card. That changes everything!

Here’s what the official UNO rules says about the Wild Draw 4 card: “You can only play this card when you don’t have a card in your hand that matches the colour of the card previously played.”

You’re probably thinking, “My opponents can’t see my cards. How would they know if I’m using my Wild Draw 4 incorrectly?” Well, the UNO folks have a rule about that too.

“If you suspect that a player has played a Wild Draw 4 card illegally, you may challenge them. A challenged player must show his/her hand to the player who challenged. If the challenged player is guilty, he/she must draw the 4 cards, plus 2 additional cards. Only the person required to draw the 4 cards can make the challenge.”

So if you’re going to use your Wild Draw 4 to prevent somebody else from calling “UNO,” you’d better have a pretty good poker face.

Next, read on to find out eight mahjong facts that will blow your mind.

[Source: Good Housekeeping]

1. The game was created on December 15 1979, by Chris Haney and Scott Abbott, two Canadian newspaper editors. Haney and Abbott were friends and came up with the idea when playing Scrabble and drinking beer. They wanted to make their own game, and soon Trivial Pursuit was born.

2. The design of the game board is based off of a ship’s wheel—six separate spokes leading to the centre or winner’s circle.

3. The artwork for the game was by 18-year-old Michael Wurstlin. He was unemployed at the time and took the job because his unemployment insurance had run out. He chose to invest in five shares of stock and earned enough money to start Wurstlingroup, a successful marketing company based in Toronto.

4. Haney and Abbott realized they needed $75,000 to create a prototype game board, the pieces, and print the cards. They searched for investors and many people turned them down. But, in the end they got 34 people to invest. Four years later, those investors were each getting five-digit dividend checks. (Check out the 60 most important inventions of the past 60 years.)

5. Trivial Pursuit hit the public in 1981. One game cost £48 (around $74) to make and it was only sold for £10 ($15). It didn’t start to make a profit until it was licensed to Selchow and Righter in 1983. (This list of amazing trivia questions will cost you nothing.)

6. Over 100 million copies of the game have been sold in 26 countries in over 17 different languages.

7. Fifty special editions of Trivial Pursuit have been made. Some of the well known ones includes:

- Star Wars Classic Trilogy Collector’s Edition

- Lord of the Rings Movie Trilogy Edition

- The Rolling Stones Edition

- Power Rangers 20th Anniversary Edition

- Baby Boomer Edition

- Trivial Pursuit Mini Pack: Hollywood Flicks

- Trivial Pursuit: Country Music

8. The original game had 6,000 questions printed on 1,000 cards.

9. Haney and Abbott were taken to court by Fred Worth in 1984 over the fact that they had copied Worth’s published trivia books. The judge dismissed the case ruling that trivia wasn’t able to be copyrighted.

10. Trivial Pursuit has made over $2 billion.

Sources: telegraph.co.uk, mentalfloss.com

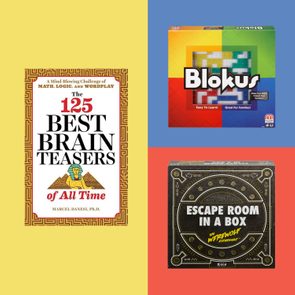

Next, check out these brain games that will help you get smarter.

What It’s About

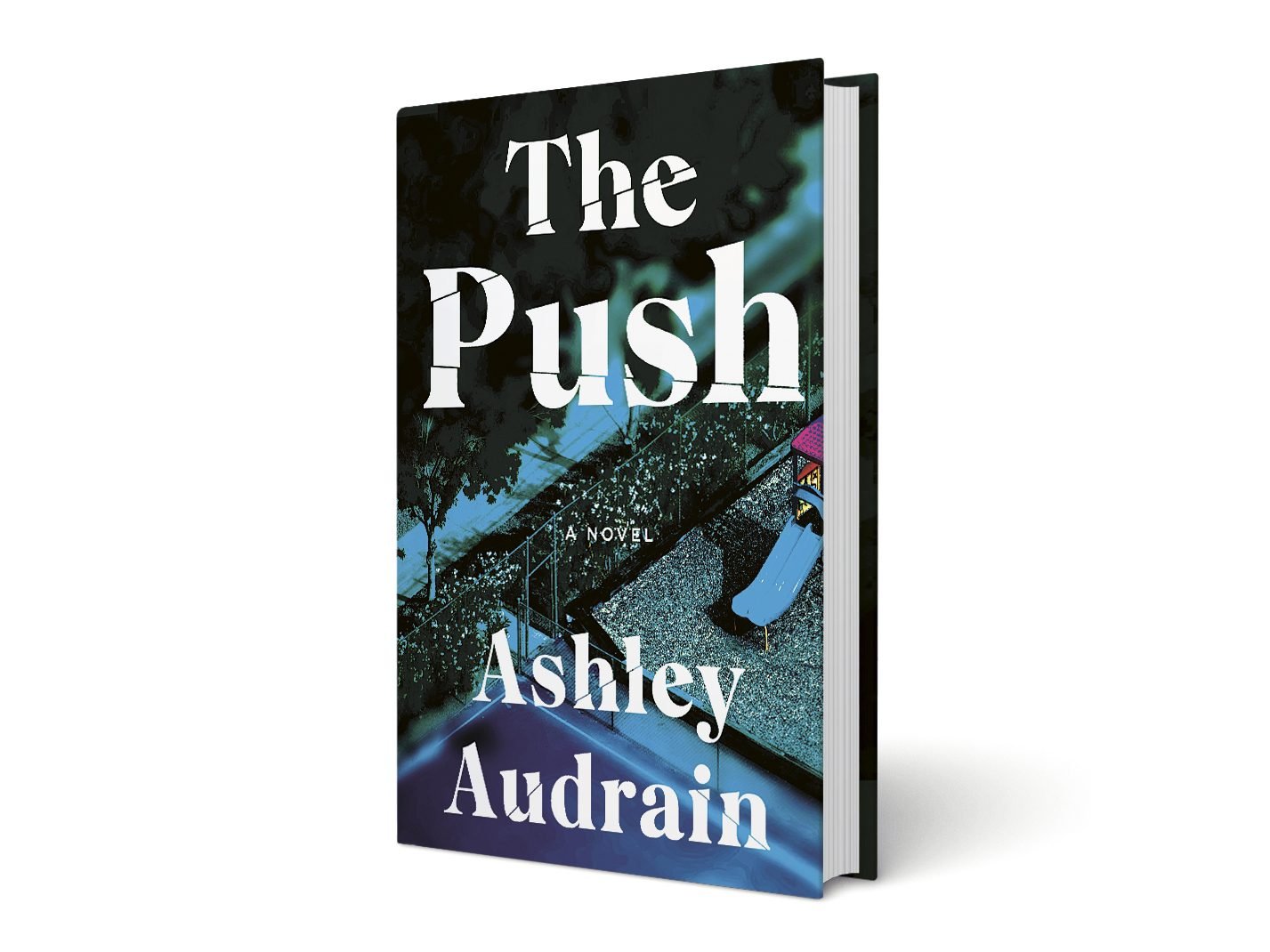

The Push by Ashley Audrain

($25, Penguin Random House)

It may only be January, but we’re already calling it: Toronto’s Ashley Audrain has written the thriller of the year. This is a book where characters stalk each other in dollar-store wigs, where grade-schoolers plot elaborate murders and where one woman throws her dead lover’s severed leg at her abusive father. It’s the story of Blythe, who’s haunted by her absent, abusive mother and grandmother, who each faced misogyny and struggled with mental illness. Desperate to break the family curse, she does what she thinks she’s supposed to do: she falls in love, gets married and has a baby. But Blythe doesn’t take to motherhood as she’d hoped, and her daughter, Violet, isn’t quite right. As a kid, she’s cold, manipulative and given to petty cruelties. Blythe seems to be the only one who can see it, and the novel hangs on this delicate, excruciating dance between bad mom and bad seed, two people who hate and need each other in equal measure. The book functions the same way, impossible to stop reading but freighted with doom.

Why You’ll Love It

What Gone Girl did for marriage, The Push does for motherhood, peering behind the cheery facade of domesticity. Audrain is a gifted storyteller, and at first glance, the book is a feast of pulpy plot, cinematic jump scares and gasp-inducing twists. Under the potboiler surface, however, it’s a haunted house of modern motherhood. Blythe mourns the loss of her independence as she caters to Violet’s needs. She blames herself when she doesn’t experience the maternal euphoria she thinks she’s supposed to feel. She resents her husband, who seems to reap all the benefits of parenting without doing much of the work—he coddles their daughter but leaves Blythe to handle all the discipline. Blythe can never quite tell how much of her anguish stems from her daughter’s supposed sociopathy and how much comes from her own failings as a mom. The plot may be pure melodrama, but the truths it reveals are as sharp as a bee sting.

Who Wrote It

Toronto’s Ashley Audrain spent much of her career touting other people’s books as a publicity director for Penguin Random House Canada. While on maternity leave, she began quietly plugging away at her own. In 2019, the first-time author became the literary world’s latest Cinderella when The Push sold in the U.S., Canada and the U.K. in a series of seven-figure deals.

Parent Trap

The Push’s Blythe joins a sisterhood of unhappy moms:

MEDEA In revenge for her husband leaving her, the original “bad mom” kills her two sons and her ex’s new wife.

CHRIS MACNEIL The mom played by Ellen Burstyn in The Exorcist needs to find a priest who can help her fix her head-spinning, projectile vomiting demon daughter.

ROSEMARY WOODHOUSE Mia Farrow plays the apartment-bound, unwilling mother to Satan’s son in Rosemary’s Baby, the thriller based on a bestseller by Ira Levin.

CERSEI LANNISTER While she’s plotting to rule the seven kingdoms in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, each of her three children perish.

Join the Conversation

Visit our Facebook page to share your experience of reading The Push with fellow Reader’s Digest Book Clubbers. Comment on plot twists and speculate on who should play Blythe and Violet in the screen adaptation (the film and TV rights recently sold in a nine-way bidding war).

Next, check out our previous book club picks for Fall 2020!

As soon as I saw the policeman knocking at my door, I immediately knew what it was about. I was sure my mother had sent him to do a “welfare check” on me and I was right. Normally people ask the police to do welfare checks on loved ones who they fear are in danger but my mom was using it as a last-ditch effort to try to get to me. Why did she have to use cops to contact me? Because I’d blocked her and the rest of my family—parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, nieces, and all but one nephew—on Facebook and on my phone. And it was the best decision I’ve ever made.

The event that triggered the mass blocking? My mom posting pro-Trump memes on her Facebook page in March of 2020. That may sound like an extreme reaction to some but those memes were the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Growing up in a racist, abusive home

My siblings and I were raised in a tiny Texas town that was riddled with racism. In fact, when I was a child, the town still had “lynching trees” and it was against the law to cut them down. My parents bought into this evil rhetoric just like everyone else there. But I didn’t. When we first moved there, I was befriended by two Black girls and my white classmates ostracized me. My second-grade teacher, a Black woman named Ms. Wells, was the first person to ever show me unconditional love.

It was a love I desperately needed—it wasn’t just people with different coloured skin that my parents hated. There wasn’t a single type of abuse that I didn’t suffer growing up. When I was finally old enough to leave, I took a job as a nanny in another state and never looked back.

I spent the next two decades trying to deal with my sexist, racist family and while I didn’t see them much, they were still a part of my life, including on social media.

Becoming a mother

In 2003, I had a biological child and when he was two, I adopted his brother, also two years old, from China. They were just four months apart in age, making them “twins” of a sort. I was overjoyed to have these two beautiful children in my life and looked forward to giving them the happy childhood I never had. But when I told my mother about our plans to adopt, her first question was, “Is he white?”

I allowed my mother (who I prefer to call my female parent) to stay in our lives because she was the only grandmother they had, due to my mother-in-law passing before they were born, and there were times we needed her to help with the kids. Even as she helped care for them and grew to love them in her way, she was still showing racism, insisting on calling my adopted son “oriental” among other things. She and other family members blamed immigrants for “stealing” American jobs and repeated other falsehoods.

As my children grew, I was able to distance myself further from my family. Even so, the stress of dealing with them caused me to have seizures and I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Yet I still felt unable to cut that final familial tie through social media.

Donald Trump’s 2016 election brought so many bad feelings

I was irate. Donald Trump was unapologetically racist and abusive and reminded me too much of how I grew up. I told everyone in my life, “If you’re a Trump supporter you’re dead to me.” I figured my family supported him but I managed to keep a “don’t ask, don’t tell” type of peace— until my mother just couldn’t contain herself any longer and began posting on Facebook in support of Trump. That was it. I was done with her. I was done with all of them. That was the day I disowned my family, severing that last electronic link to them.

I didn’t say a word as I blocked her and my entire family on Facebook, not just from my account, but I also blocked them from my husband and children. I blocked them on other social media platforms, email, and their phone numbers. It took just five minutes.

I finally felt free

Immediately my stress levels went down and my mental and physical health improved. My kids felt better as well. I realized I was teaching them a valuable lesson on how to set boundaries and protect themselves. By doing this, I was able to be the parent that I always wished I’d had.

Once she realized what I’d done, my mother attempted to contact me once through the police but after I told them the situation, it never happened again. Occasionally my family sends things in the mail but my husband intercepts them before I can even see them. It’s all worth it.

Blocking my family was the most liberating, freeing thing I have ever done. My only regret is that I didn’t do it sooner. Life is too fragile and short to keep toxic people in it, even if it’s just on Facebook.

Next, read these 25 powerful quotes on racism from history’s most inspiring activists.

Most of us have done it: It’s midnight, we really should turn off the phone and go to bed, but we can’t stop “doomscrolling” through news apps and social media to read about the coronavirus pandemic. Or civic unrest. Or racial injustice. Or natural disasters. Or all of the above. There’s no doubt 2020 was a doozy of a year—and 2021 isn’t starting out much better—leading to a dramatic increase in the use of Facebook, Twitter, and media sites. Why? “Many who experience these scrolling behaviours find there’s an urgency to look, learn, and understand the sensational issues going on in the world,” says Deborah Serani, PsyD, a psychologist and professor at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York.

But an obsessive doomscrolling habit is neither helpful for staying informed, nor good for our health. One 2020 Dartmouth study found that college students’ amount of phone usage and COVID-related news exposure was associated with greater reports of anxiety and depression. “There is no question that doomscrolling can be addicting,” says psychologist Sherry Benton, PhD, founder and chief science officer of the tele-therapy company TAO Connect. “The more dramatic the news, the more we tend to get lost in it.”

But with bad news always at our fingertips, how can we limit our consumption before it becomes unhealthy? We asked our experts for advice.

What is doomscrolling?

If you’re wondering “what is doomscrolling,” it’s not an official psychological behaviour and hasn’t yet made it into the dictionary. But Merriam-Webster has named it one of the “words we’re watching,” explaining that doomscrolling means “the tendency to continue to surf or scroll through bad news, even though that news is saddening, disheartening, or depressing.” The term first appeared several years ago, and gained popularity in the tumultuous year of 2020; it can also be called “doomsurfing.”

It’s not that being informed is bad, but it’s the constant intake of negative information that’s a problem. “Essentially, this is a consciously focused activity of scrolling from one terrifying story, video, or news coverage to another,” says Serani.

Is it new phenomenon?

If you’re doing an Internet search for “what is doomscrolling,” you might not find anything more than a couple of years old. But although greater social media and Internet access has fueled the phenomenon, research has shown exposure to bad news following traumatic events has also been a problem in years past. One University of California study from 2013 found that exposure to four or more hours a day of early 9/11-related television was linked with greater incidence of health problems several years later. Another study found that greater media exposure to the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013 was linked with acute stress. “Doomscrolling doesn’t only take place on your phone or computer,” Serani says. “Remote-scrolling—going from one television station to another during traumatic events—is also a health concern.” Having constant, easy access to bad news has likely just heightened a behaviour we’ve already been doing.

Can you blame the media?

In part, maybe. “When media companies profit through advertising and rates related to the number of readers, headlines might be written more dramatically to gain views,” Benton says. This also isn’t new, though—writers have used sensationalist headlines to sell newspapers for more than a century. But social media and news apps have another ace up their sleeve for pulling you in and getting you to keep reading. “The algorithm on sites might also recommend you more ‘doom and gloom’ articles the more you read them,” Benton says. Soon, your newsfeed is filled with everything going on that’s bad—and nothing that’s good.

Why do we doomscroll?

Doomscrolling means we develop an almost uncontrollable need to keep reading about bad things. “People who doomscroll are, indeed, quite upset, but instead of sealing themselves off from the trauma, they actually seek more stimulation from the unnerving issue,” Serani says. The clinical term is “counterphobic” behaviour, she says: Instead of fleeing from the thing that scares us, we are attracted to it. “They want to know more. They need to know more. They counter the feelings of anxiety by watching and re-watching,” Serani says. “It becomes a kind of compulsion, to repeat the disturbing news over and over.”

Plus, humans don’t like uncertainty, so we keep reading, hoping to figure things out. In doing so, we’re trying to make sense of traumatic events, Serani says.

Does it have a deeper biological origin?

Our tendency to seek out bad things is actually a primitive behaviour. “Detecting danger is a central function of our brain and central nervous system. In our cave-dwelling days, this prevented us from threats related to attacks from animals or people, and from being caught in dangerous weather,” Benton says. “The problem is that our nervous system still works the same in our current day and age and doesn’t discriminate between real threats and the bad news we read about. That bad news can send our bodies into high alert.” As a result, people may have a “negativity bias” that draws them to bad news, which could be the reason for the old journalism adage, “If it bleeds, it leads.” You should also be aware of the sneaky signs you’re actually reading fake news.

Do we like to be scared?

Oddly, humans’ penchant for seeking out and identifying danger can chemically give us a natural high, which is also why we sometimes like to be scared. “Humans enjoy the adrenaline rush of fear—it’s why we ride roller coasters and go to haunted houses around Halloween,” Benton says. “We get that same rush when our fear response is triggered reading disturbing material. Thrillers, mysteries, and other adrenalin-triggering books are really popular for a reason.” Seeking out negative news may also be part of this phenomenon because it gets our blood up: There’s a certain thrill in reading about disaster.

Why can it be problematic?

So if doomscrolling can actually make us feel good, why is it so bad? “Too much consumption overwhelms our system,” Benton says. “We begin to suffer from stress, anxiety, or depression. Our bodies produce high levels of a natural steroid called cortisol, which can wreak havoc on your body. One might experience things like digestive problems, headaches, sleep problems, memory or concentration impairment, and heart disease. Cortisol and chronic stress can also contribute to weight gain.” (Find out more silent signs you’re suffering from high-functioning anxiety.)

In addition to mental problems, “physical issues like increased blood pressure, cardiac illnesses, chronic pain, sleep disturbances, and lowered immunology are connected to experiencing bad news on a daily basis,” Serani says.

How can it affect your worldview?

Plus, exposure to too much bad news can lead you to have a negative outlook on the world around you, even when you’re offline. “The cumulative exposure to stories of trauma, crisis, fear, and helplessness change our social expectations, making us believe that the world is truly a scary place,” Serani says. “Doomscrolling can make us feel utterly hopeless.” Even though the world has presented us with challenging situations lately, it’s not all bad; but too much time exposed to bad news can warp our perception of reality. “When you read article after article of horrible news, it’s easy and not uncommon to feel like the world is falling apart,” Benton says.

How much is too much?

The exact amount of bad news to take in may depend on the person. One 2020 German study on the effects of COVID-19 related media exposure found seven times per day and two and a half hours to be the tipping point; but that might even be too much for some people. “If you are spending more than an hour or two to stay caught up on the news, that is a sign you probably need to shift your focus to something else,” Benton says. Beyond a specific time limit, you’ll also want to consider how your news habit is affecting you physically and mentally. “First, take a step back and assess how much time you’re spending on the habit,” Benton says. “Additionally, when you start to have difficulty sleeping, headaches, or digestive problems—that is an important sign to consider changing your media consumption habits.”

How do you stop doing it?

Stopping your bad news habit means setting limits for yourself. “Statistics report that the average media user is online or watching television over six hours a day,” Serani says. “When it comes to the consumption of media, it’s really important to have structure.” Don’t go down the internet rabbit hole, especially right before bed. Instead, “if you feel a need to know what’s going on, give yourself a limit of one hour a day for scrolling current events,” Serani says. “You’ll be informed and have greater well-being with this approach.” Serani also suggests turning off notifications from news apps (or deleting the apps all together) in order to keep the boundaries you’ve set and not get sucked back in. Imagine the things that could happen if social media disappeared.

Spend time in the real world

Social media can help us feel connected—but too much time on it, especially when it’s negative and unhealthy—can affect our real life. (Check out the hidden downside of your social media obsession.) “Take time away from your phone or computer by engaging in non-technology and feeding your senses,” Serani says. “Experiences like exercising, talking with loved ones, cooking, cuddling with a pet, listening to soothing music.” It can feel odd to disconnect when we are so used to being online, but it can help us shift our focus. Benton also suggests self-care practices including relaxation and mindfulness techniques: When you’re engaging in mindfulness, you’re living in the moment by giving your full attention to friends and family, or participating in hobbies and activities you enjoy. Here’s what can happen when you start meditating every day.

Shift the media you consume

Even when you are online, try to balance your intake of the negative with the positive. “The idea of searching for good news is a brilliant way of inoculating yourself against doomscrolling,” Serani says. “Taking in media that contains positive, meaningful, and pro-social events reduces anxiety, sadness, and feelings of hopelessness, be it a human interest story, an uplifting video, or even something silly, like tiny goats dressed in sweaters, jumping and playing—my upbeat find for today!” Doomscrollers might find some guilt in searching out something whimsical instead of the more crucial news of the world, but it’s important for your health to do so. (Here are 100+ good news stories from around the world to get you started.)

Alter your algorithms

Plus, searching out good things might inadvertently help your newsfeed become more balanced. “When I was shopping for a new puppy a couple of years ago, I noticed my newsfeed started to fill with cute puppies; when I was renovating a room in my house, I started to get stories in Architectural Digest and other decorating magazines,” Benton says. “My interests and searches were shifting my algorithms and diversifying the articles suggested. In this same way, we can easily modify our newsfeeds intentionally. Search terms that are interesting to you rather than stressful.” Those might be hobbies, travel stories, animals, or anything that you find pleasant, she says. Lighten things up with comedy shows or humorous books as well.

Next, check out a wellness counsellor’s tips on how to cope when the world seems like a horrible place.

Dancing Queen

“Welcome to Hell, ladies,” he says in an eastern European accent. I grimace as he presses down on my stiff upper back, attempting to coax out an extra millimetre of flexibility. I’m finally ticking adult ballet class off my bucket list, but now I’m wondering what possessed me to do this.

When I was a little girl in the ’60s, I begged my mother to let me take ballet class. I loved the pink tutus, the pretty buns, the dreams of gracefully dancing across the stage like the Swan Princess. She sent me off to figure skating and Brownies, and yet, for some reason that’s still a mystery to me, she wouldn’t budge on ballet lessons.

With the distractions of adolescence and then the demands of adult life, my hopes of taking ballet lessons were put on hold. But every so often, usually while watching an inspired performance of Swan Lake, those little pangs of unfulfilled desire would speak up and say that I should take lessons before it’s too late.

And here I am—more than 50 years after pleading with my mother—finally taking the plunge.

My class in Vancouver is called Absolute Beginner Adult Ballet, and I’m a good 30 years older than the rest of the participants. Our instructor, Mr. C., is trained in classical Russian ballet and has had an illustrious dancing career. He’s an imposing presence with penetrating dark eyes and a penchant for tailored black attire.

My hair’s in a slicked-back bun and I’m wearing second-hand pink ballet slippers. The tutu-wearing window has closed for me.

We start with warm-up exercises. The precise, controlled movements are so different from what I’m used to in my regular aerobics and strength-training classes. I’m in good shape, but this warm-up is killing me. Judging by the groans, my younger classmates are faring no better. “Did I tell you to stop? Keep going, ladies,” says Mr. C. He’s got a devilish grin, revelling in our agony.

I experience a flashback to elementary school gym class in suburban Montreal. For years, I had an evil gym teacher who hailed from somewhere in the former Soviet bloc. He delighted in beaning timid little girls with dodge balls and mocking our feeble attempts at hoisting our scrawny bodies up on chin-up bars. I’ve since had a lifelong disdain for dodge ball. But I’m a mature adult now, confident, not easily intimidated. I can even do a chin-up (sort of). Ballet and Mr. C. don’t scare me.

“Okay, ladies, hands on the barre. Stand up tall,” he instructs. How hard could this be? Mr. C. moves down the line of students, critiquing our posture. He points his finger at various body parts while sternly giving feedback: “Head up, neck long, chest proud, stomach in, back straight, buttocks tight.” I’m last in line and have taken note of every previous adjustment. I’ve got this. He looks at me, and I instantly know that I’ve missed something. “Breathe!” he says. “It must look effortless. No one wants to see a clenched face. It’s ugly.”

Mr. C. has us doing a little routine at the barre. “Pointe, demi-pointe, plié,” he cues. I’m concentrating hard, trying to master the terminology while executing the corresponding movement. I’m sure it doesn’t look pretty, but he fails to notice as he admonishes another lady for not keeping her head up. “You must look proud, like a rooster.” Thankfully, he doles out feedback in equal measure.

We are practising “port de bras,” a ballet term for movement of the arms. Mr. C. tells us that our shoulders must be strong and our lower arms soft and graceful. I flutter my arms, channelling my inner swan. “Your hands, they look like claws,” he chides. “No one wants to look at that.”

I get nervous when Tchaikovsky begins to play. Not only do I have to remember the terms, the steps, the graceful arms and the breathing, now I also need to keep in time. “Just listen. Feel the music,” he implores.

Mr. C. sees our perturbed expressions. “I’m not here to tell you how wonderful you all are. I’m here to teach you the fundamentals of classical Russian ballet,” he proclaims. He launches into a monologue about how we’re all too soft in this country, too in need of constant praise. I actually agree with him on this one.

After a few sessions, I find myself looking forward to ballet class in much the same way that I looked forward to roller coaster rides when I was a kid—with a mix of angst and excitement. Between classes, I check my posture in every window I pass and indulge my fantasies with grands jetés between the kitchen and the living room. I’m progressing, albeit slowly. My hands are marginally less claw-like and my posture a little more erect.

Mr. C. is still a tad intimidating. Nonetheless, I’ve come to appreciate his demands for perfection, his discipline, his passion, his directness and his sense of humour.

We’ve progressed to the middle of the room. Mr. C. demonstrates a beautiful diagonal pattern across the floor. I summon my inner swan once again and pretend I’m on stage, dazzling the audience with my grace.

“Too much drama,” he yells.

I smile. It’s not exactly a compliment, but it’s a whole lot better than “ugly.”

Learning ballet as an adult has been a much bigger challenge than I expected. I know that I will never master a grand jeté (or even a petit one, for that matter), but I’m glad that I finally took the initiative and that ballet still holds the same allure for me as it did when I was a little girl.

Sadly, after only a few months of lessons, COVID-19 restrictions put an abrupt end to my blossoming ballet skills. I know I’ll eventually return to my lessons—it’s my new roller coaster thrill, and I simply can’t resist.

Find out why learning new skills as an adult is easier than you think!

© 2020, Caroline Helbig. From “Adult ballet classes are not for the faint of heart,” The Globe and Mail (August 19, 2020), theglobeandmail.com

100 Tricky Trivia Questions" width="295" height="295" />

100 Tricky Trivia Questions" width="295" height="295" />