The idea behind freezing food is saving time and saving money. Time, because you’ll have ingredients (or fully cooked meals) on hand for when you need them. Money, because you get a better deal by buying in bulk.

Believe me, cooking one of our freezer meal recipes is always a smart choice. How frustrating, then, to open your freezer to find your conveniently stored meal dried out, ice-encrusted and far from appetizing. You’ve been hit by the dreaded freezer burn.

What Is Freezer Burn?

We associate freezer burn with the layer of ice on the surface of the food, but the ice is only a symptom of the problem. The ice crystals come from the food itself; if there’s warmer air next to the food, moisture escapes and then freezes at the surface. Unfortunately, this also dries out the food itself. Though food with freezer burn may be safe to eat, your frozen chicken dinner may not turn out too tasty.

How to Prevent It

The key to preventing freezer burn is to prevent the moisture from escaping in the first place. For this to happen, you’ll want to keep two things in mind: keep temperatures consistently cold and keep the air out. This helps freeze the food fast and keep that icky freezer burn from forming. Keep the following tips handy the next time you plan on tossing together an easy freezer meals.

1. Set your freezer to the right temperature.

Use a thermometer to ensure that your freezer temperature is at or below freezing. Depending on your make of freezer, this could be “Cold,” “Low,” or an actual temperature. (Here’s the best temperature to set everything in your home.)

2. Chill your food before freezing it.

Putting hot food directly in the freezer brings the temperature of the freezer up almost as fast as it brings the temperature of the food down. Not only that, it will affect any food close to the hot food, making a warm place on the surface for freezer burn to strike. Put your food in the fridge for one to two hours before putting it in the freezer for long-term storage.

3. Freeze your food in small batches.

Filling the freezer with food all at once will bring up the temperature, and it will take much longer to get down below freezing point. Instead, put in just a few items at a time. (Try this freezer sweet corn recipe for fresh corn any time of the year.)

4. Don’t overfill—or underfill—your freezer.

Already frozen food acts like ice in a cooler, and helps chill other food. But an overstuffed freezer prevents the even circulation of cold air, creating warmer pockets. Ideally, your freezer should be about three-quarters full. If you have the room, use freezer shelves to give your food a couple inches of air beneath it, too.

5. Clean out and organize your freezer regularly.

Know what’s in it and how to find it quickly, without a lot of open-door time. Follow these tips on how to clean a freezer (and how often you should be doing it!)

6. Use freezer-safe containers to store your food.

Plastic containers, glass containers or jars, or freezer bags all work great. Be sure you have freezer bags instead of “storage bags”; storage bags use a thinner plastic, and aren’t designed for the freezer. (These are the 15 food storage guidelines you didn’t know.)

7. Give your food an extra layer of protection.

You can do this by wrapping it in plastic wrap or aluminum foil before putting it in your container or freezer bag. Only use plastic wrap, waxed paper and aluminum foil if you are also using a container or freezer bag. None of these, on their own, will keep enough air out to prevent freezer burn. If you’re storing a liquid, like freezing soup, for example—pour it into the container, leaving about ½ in. of headroom (the liquid will expand when it freezes). Cover the surface of the liquid with plastic wrap, smooth the plastic so that it makes contact over the surface of the food, then put the lid on the container. (This is how long you can really freeze food for.)

8. Squeeze out the air.

When using freezer bags, press out as much air as possible from the bag before freezing the food. If you have a vacuum storage system, this is the best possible solution.

9. Know when to toss it.

Finally, it may go without saying, but don’t keep food for too long. No matter how well wrapped and protected, food will hit its expiry date after about 9 months in the freezer. So make sure you record the date on the food you freeze, and that you use or discard it after 9 months.

Next, here’s 13 foods you should never eat past the expiration date.

Making Them Feel Safe in the Stacks

When I got my first library card in the mid-1950s, my love for the institution blossomed.

From the age of eight, I was allowed to walk from my house in Mount Royal, Que., across the wooden footbridge over the CN rail line to where the municipal library was housed directly above the police station. Once the librarian gave me my membership card, she suggested that I might enjoy a series of books written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, starting with Little House in the Big Woods.

The memory of curling up in an armchair and disappearing into the faraway world of pioneer life is still vivid today. I was from a Greek household, so the details of homesteading in the American West were exotic: chopping down trees to build a house, planting crops, the isolation, it all fascinated me. Time disappeared. No longer restricted to the here and now, I was free to imagine myself as a pioneer girl. I was addicted.

But the municipal library’s collection paled in comparison to what was available to us at high school. There, I read novels written by the authors we were studying in class: Charles Dickens and Joseph Conrad, Mark Twain and Emily Brontë.

During the summer months, I was caught up in Gone With the Wind and Anna Karenina or lost in the exciting and strange worlds of Ray Bradbury.

When I studied English literature at university, I thought it best to build my own library. And later, when I taught English at a high school, I continued to collect books. Forty years into my collecting, I realized that all those books had become a part of the house, like wallpaper or wood panelling. Suddenly I saw them as vanity and an insidious aspect of consumerism. Why did I have to keep every book? I held on to a select few and donated the rest. My home library is now filled only with books that have enriched my life and are of interest to my family and friends. I regularly prune my collection. A new book rarely stays with me for long.

Toward the end of my teaching career, I became a teacher-librarian. This position reignited my love and appreciation for how wonderful it is to be surrounded by books. And the school library indulged my passion for books even more.

I had a generous budget, and I searched for books that would interest my teenage audience and hopefully spark a love of reading in them. Fantasy. Science fiction. Horror. Graphic novels. I couldn’t keep the Twilight series on the shelves—too many kids wanted to borrow them. Biographies of sports heroes were in hot demand. Students raced to the library as soon as it opened (even in our digital era) to take out several books of their favourite manga series. I suggested Three Day Road, De Niro’s Game and The Ghost Road to senior boys for their independent study assignment, and the girls loved Lullabies for Little Criminals, A Complicated Kindness and Fall on Your Knees. I bought books that students asked for and ones that I wanted to read.

I quickly realized that the library wasn’t just a place to do research; students came for other reasons, as well. I noticed that some students lined up first thing in the morning, returned at break time and spent the whole lunch hour tucked away in a carrel. These were the loners and the marginalized, the ones who felt safer in the library than in the hallways or in the cafeteria where they could be bullied or harassed.

There was the young man who hid in the stacks reading philosophy books, refusing to sign them out for fear of being ridiculed at home. A young woman, who read every book on human anatomy and diseases, dreamed of being a doctor, but her family was too poor; she would have to find full-time work after graduation. I noticed that students searched for books on specific topics instead of using computers: sexually transmitted infections, drugs, LGBTQ+ issues, mental-health issues. I realized that computer screens were too visible, so I bought more books on those topics.

I bought sofas and easy chairs. The conference room doubled as an art gallery and a meeting place for students to talk about ideas, play chess, start knitting circles and make posters for their clubs. The library became an inclusive public space, democratic and safe for everyone. The circulation rates for books rose five to 10 per cent every month.

My years as a teacher-librarian—non-judgmental, resourceful and always accommodating—were the most rewarding of my career. Even though I was an authority figure, I wasn’t involved with student assessments and evaluations or restricted by the rigid structure of the curriculum. I was free to make the library a comfortable and exciting place to learn.

Whether libraries are located in schools or in communities, I believe they provide students and the public with an opportunity to engage with the past, the present and the future; all that is required is a modicum of curiosity. Libraries are vibrant and fluid places that help us to adjust to the world, and their doors must be kept open to everyone—for free.

Next, see a list of the Reader’s Digest Book Club picks.

I was 12 when my immune system suddenly wiped out the insulin-producing beta cells in my pancreas. The first symptoms arrived when I was in Paris, on a family vacation. I started urinating like crazy, drinking litres of water each day to compensate. My memory of the Champs Élysées is not the beauty of the architecture but the number of public bathrooms I had to duck into along the way.

It was 1986, a different era in diabetes care, and the doctors I eventually saw told me I could still eat whatever I wanted, so long as I injected enough insulin to compensate. I was told that diabetes is manageable, that you can live a good life with it—both mostly correct though not always straightforward. Yet my diagnosis still changed how I saw myself. I contained a flaw, my body now a series of problems that constantly had to be solved.

Diabetes is a tricky disease, both to live with and to understand. It all comes down to the pancreas: in normal circumstances, the organ produces insulin, a hormone that controls blood glucose. Diabetics either can’t produce enough insulin (which causes the more manageable Type 2 diabetes) or any at all (Type 1). Because of this, our bodies can’t handle the sugar we consume. When blood-glucose levels drop too low or surge too high, it can lead to serious health complications.

Thankfully, new medical and technological advancements have allowed Type 1 diabetics—myself included—the opportunity to live full, relatively normal lives. Insulin pumps let us forgo regular insulin injections: these small devices run a thin tube through a tiny hole in the abdomen to deliver a programmable stream of medication. Sensors, called continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), can be placed under a diabetic’s skin and will send updated blood-glucose levels to users’ smartphones every five minutes. Managing Type 1, however, is still a full-time job—one where, if you don’t do it just right, you’ll feel terrible. Or get sick. Or die.

The magic number for blood glucose is typically 5 millimoles per litre of blood, and consistently hitting it is a challenge, even with the most up-to-date tech. Diabetics still need to consider many factors to determine how much insulin they need to take: what they’ve eaten (and are going to eat), how much exercise they’ve done (and will do). Everything from stress to sex can affect blood sugar. The trick for managing it all is to think like a pancreas—a problem, since nobody really understands how a pancreas thinks.

But what if a computer could do all the hard work for you? Enter the artificial pancreas, the holy grail of diabetes management. Currently, a person might use both an insulin pump and a CGM to help manage their diabetes. Unfortunately, these pieces of tech don’t talk to each other. The person with diabetes is still the one who’s constantly making decisions, monitoring and taking everything into account. But an artificial pancreas, also known as “the closed loop,” uses a piece of code to connect them, mimicking a real pancreas. Once connected, the loop would work in the background like any other organ.

It sounds like the stuff of science fiction. Officially, it will be at least another few years before people with diabetes can obtain an artificial pancreas. But, unofficially, well, that’s a different story.

How to Hack a Pancreas

I first met Kate Farnsworth and Pina Barbieri in November 2017. The mothers are based in the Greater Toronto Area and both have teenage daughters—ages 13 and 15, respectively, at the time—with Type 1 diabetes. Farnsworth tells me about the fear she felt when her then eight-year-old daughter, Sydney, was diagnosed in 2012. She began looking everywhere for information—and hope.

In May 2014, she found a Facebook group called CGM in the Cloud, an international community of over 30,000 members with a do-it-yourself ethos. Through the group, Farnsworth followed instructions on how to adapt Sydney’s CGM. Suddenly, she was able to pair Sydney’s CGM with a regular smart watch, giving her the ability to check Sydney’s blood-glucose numbers wherever she was. She was even able to set up an alarm to warn her whenever Sydney’s levels were trending too low.

Two years later, she heard about a group of amateur coders from the U.S., most of them Type 1 themselves, who were fiddling around with insulin pumps and CGMs, looking for ways to improve the devices. The amateur coders pooled their discoveries and created an iPhone program called Loop (an Android version, called OpenAPS, was also created around the same time). Loop is not available in the App Store or through any official channels—no doctors will prescribe it. Users need to find the instructions online and build the Loop app themselves. This bit of free code, paired with a hacked-together insulin pump and CGM, is an artificial pancreas. Farnsworth knew that Sydney needed to have it.

I feel uneasy about entrusting my life to homemade software thrown together by some DIY hackers. The technology sounds revolutionary—if it actually works—but it also feels like giving up control. After living with diabetes for 33 years, I have trouble believing that a few lines of code can understand my body better than I can.

“When Sydney started on Loop, my entire role as a parent changed. It went from me micromanaging her diabetes to the system doing almost everything,” Farnsworth says. She no longer needed to wake up in the night worrying about Sydney going low; Loop took care of it. “Every night she goes to bed, I sleep through the night, and she wakes up usually at the same number,” she adds. “It’s amazing.”

“Yeah, she actually gets some sleep,” says Barbieri.

Suddenly, an alarm goes off. It’s Barbieri’s smart watch. Her daughter Laura’s blood sugar is 17.3, which is very high. Barbieri texts her: “You okay?”

Laura: “Yeah, taking more insulin.”

Barbieri: “Good.”

This exchange between mother and daughter floors me. I’ve always felt that there’s something intimate in a blood sugar level: shame if you’re too high, pride in perfect 5s or 6s, anxiety if you go too low. It’s like having a daily report card on how you’re living your life. Managing the disease was my responsibility, and I’d tell myself that I needed the privacy. I’ve never shared my numbers with anyone other than my doctor. As I listen to Farnsworth and Barbieri, I wonder if I’ve been thinking about diabetes all wrong.

My First Artificial Pancreas

I spend the next few months reading posts in the Looped Facebook group, which, at the time I joined in January 2018, had about 6,500 members worldwide. Approximately 1,000 of them are already “Looping.” Others, like me, are simply curious. Farnsworth explains that since Loop has given her and Sydney so much, she feels compelled to give back to the community: she’s the creator of the Looped Facebook group and is one of the two volunteers who run the page, spending hours each week answering questions and offering advice.

The more I learn about Loop, though, the more hesitant I feel. For one thing, Loop requires having an insulin pump that can be hacked and reprogrammed, and these are rare: when medical-device developer Medtronic realized there was a security flaw in its products, it changed its design. This change makes Looping with new pumps impossible, meaning would-be Loopers need to find old, out-of-warranty devices. They also need to order a RileyLink from the United States—a Bluetooth device that lets an iPhone communicate with a pump. After all of that, they need to build the Loop app themselves.

So I’m not quite sure what to say when Barbieri calls to tell me that she and Farnsworth would like to organize a Loop-building session with me and a few others. Barbieri has an old, Loop-able pump I’m free to use. I can have her daughter’s extra RileyLink so long as I replace it. The entire cost of this life-changing artificial pancreas? $250. Amazed by the generosity of a virtual stranger, I thank her. But when she asks me to commit to a date, I’m evasive.

Days pass, and the dream of the closed loop clings to my imagination. I contact Health Canada’s Graham Ladner, scientific evaluator of the Medical Devices Directorate, to ask about the elusive artificial pancreas and whether we’ll ever see an approved version on the market. Ladner explains an insulin pump is usually a class III medical device, but once you “close the loop” by having the pump automatically communicate with a CGM, it becomes class IV, meaning more restrictions and more difficulty getting approval. Just like humans, machines can make mistakes, too.

If I’ve closed the loop and am using an artificial pancreas, my CGM could, for example, erroneously say I have a blood glucose level of 16.5. In truth, I may actually be at 7, but in a closed-loop system, the pump will automatically give me too much insulin. I’ll end up with severe low blood sugar and could lose consciousness.

Even in normal use, insulin pumps can be dangerous. According to a November 2018 CBC investigation, more people have died because of insulin pumps than any other medical device on the market, with Health Canada concluding they may have been a factor in 103 deaths and over 1,900 injuries from 2008 to 2018. Such potential risk only becomes magnified when you leave things to a computer algorithm. “The closing of the loop introduces new patient hazards,” Ladner adds, “and we need to be convinced that it’s safe.”

After I hang up the phone, I head back to the Looped Facebook group. I’m not sure what I’m looking for. Confirmation? A perfect solution? I read a mother’s comment about frustrations managing her child’s diabetes. Fellow Loopers offer a chorus of support and advice. I choke up, break down and cry. Maybe it’s the exhaustion of living with diabetes for three decades. But as I read the various Facebook comments, I’m amazed by the care people take in volunteering their time, feedback and insights. Which is why I decide to do it. Will the Loop be better than what I have? I don’t know. But, for the first time, I won’t have to do it alone.

The Perfect 5.0

It’s a Saturday morning when we all meet to build me my very own Loop. Farnsworth hands me an old purple Medtronic 554 pump. Barbieri passes me a lighter-sized box: the RileyLink. Once connected, these two devices will work alongside my CGM and the Loop code to create my artificial pancreas. We gather at a table. Farnsworth leads us through all the coding steps. A message appears on my laptop screen: “Please understand this project is highly experimental and not approved for therapy.”

By the end of the afternoon, I’ve built my first app and transferred it onto my phone. We connect finicky wiring to tiny battery packs and flick on our RileyLink switches. When I tap the Loop icon, I see graphs highlighting my glucose trends, active insulin, insulin delivery time and carbohydrate intake. My CGM numbers appear on the top row. To the right, it shows how much insulin the algorithm is adjusting. To the left, a small circle glows green. It means I’m Looping. My artificial pancreas is alive.

In the days that follow, Barbieri and Farnsworth continue to guide our group. At first, I feel overwhelmed and am constantly worried I’m going to forget something. Sometimes the RileyLink craps out and the Bluetooth goes down, and I feel panic in the moments before it reconnects. There’s no question that the system isn’t perfect. But after my first night’s sleep, I wake up to a perfect blood glucose of 5.0. And then it happens the next morning. And the next.

I’ve now been on Loop for over two years. I wake every morning to near-perfect blood sugars. The Looped Facebook group has grown exponentially since then, surpassing 23,000 members. In April 2019, the Omnipod, another commercial pump, became Loop compatible. And, in a gesture that shocked many, Medtronic recently announced that it will work with the FDA and competitor Dexcom to let their insulin pumps and CGMs speak to one another via Bluetooth and an app called Tidepool—essentially Loop gone legit.

With so much potential change on the way, I ask Farnsworth what’s going to happen when a government-approved artificial pancreas as good as Loop—or better—is finally available. I ask if it will bother her to lose this close community she’s helped create. “Honestly,” she says, “I would love to be put out of my volunteer job.”

I’m not sure how I will feel when that day comes. After all, Loop has changed my relationship with my health and with myself—life is more than just a report card, diabetes more than a mere flaw.

© 2020, Jonathan Garfinkel. From ‘‘Hacking Diabetes,’’ The Walrus (January 7, 2020), thewalrus.ca.

While a text may seem perfectly normal, it could be from someone with malicious intent—someone who wants to steal your identity, your bank account number, or other sensitive information. A recent report by the cybersecurity company Proofpoint found that 84 percent of organizations surveyed faced texting attacks. But companies aren’t the only ones being targeted. Scammers are sending scam texts to individuals, as well. This practice is called smishing. Here’s what you need to know about it—and how to protect yourself.

What is a smishing attack?

Smishing attack sounds a little scarier than it actually is. It isn’t really an attack—it’s more of a finesse. The scammer is basically trying to trick the targeted person on the other end of a text message.

Smishing definition

Smishing is a type of phishing attack that uses social engineering to get personal information about someone using text messaging. (Here’s how to spot Apple ID phishing scams.)

What it is

Basically, these fake texts are an attempt to get your personal information by pretending they come from sources you know and trust, like your boss, the IRS, or a bank. According to Ryan Prejean, help desk lead at Guardian Computer, an IT support and service company based in New Orleans, these texts often include messages like:

- They’ve noticed suspicious activity or log-in attempts

- There is a problem with your account or payment information

- You must confirm personal information

- You need to click on a link to make a payment

- You’re eligible to register for a government refund

- You’re being given a coupon

- Your child is hurt and personal information needs to be sent for their treatment

- You’ve been overcharged for something and you’re being offered a refund

- You’ve won a prize and you need to claim it

All of this is an attempt to get you to give them personal information like your social security number, bank information, or credit card details. A good smishing attack can be used to steal your identity in order to drain your bank account, charge up your credit cards, or take out loans in your name. (Here’s what you need to know about identity theft in Canada.)

Why it’s on the rise

There are many reasons why smishing is on the rise. One major reason is that it’s an easy scam to execute. All the scammer needs is a few phone numbers and a tricky way to get people to reply to a text so that they can get information.

Plus, people love text messages. Around 95 percent of text messages are opened and responded to within three minutes. Only 20 percent of emails are even opened, let alone replied to, so you can see how texting scams can be more appealing to a thief. (These are the four things hackers can do with your cell phone number.)

What is an example of smishing?

Spam texts usually use three steps to trick their victims. First, the company’s name isn’t in the text. Second, the text contains a shortened link (usually a bit.ly link) so that the website isn’t clearly identifiable. Third, the text is urgent to get victims to take action while they are off-guard.

Here are some example of smishing texts:

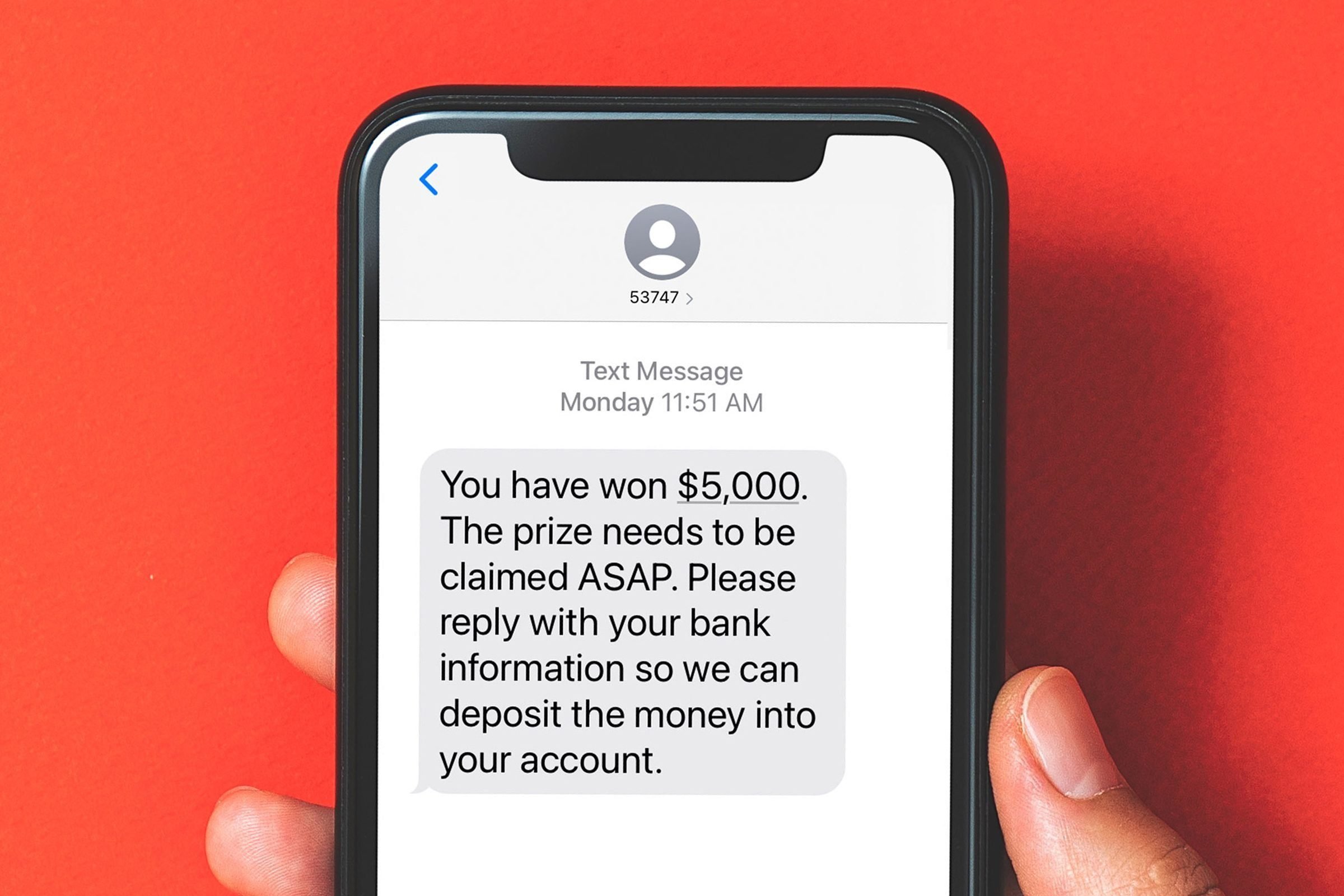

- “You have won $5,000. The prize needs to be claimed ASAP. Please reply with your bank information so we can deposit the money into your account.”

- “Your package has been lost. Please click here for more information: http://bit.ly/123R4m”

- “Your IRS tax refund has been denied. Click here to file a review in 24 hours: http://bit.ly/sdfsd5”

How to protect your phone against smishing

Though preventing this scam completely isn’t possible, you can stop a lot of it by setting up spam filters on your phone. To set up the filter on your iPhone, follow these steps:

- Go to the Settings app

- Tap Messages

- Find the Filter Unknown Senders option

- Turn it on by swiping the button to the right

If you have an Android phone, follow these steps:

- Go to the Messaging app

- Tap the three dots icon in the upper right of the screen

- Choose Settings

- Tap Spam Protection

- Turn on Enable Spam Protection by swiping the button to the right

Some Androids don’t have filtering, so if you can’t find the Spam Protection option, your phone probably doesn’t filter messages. In that case, you’ll need to install an app like Nomorobo or RoboKiller. You may also be able to use filtering tools that are offered by your wireless carrier. (Learn how to spot Apple ID phishing scams.)

What to do if you get a smishing text

If you get a smishing text, don’t reply. Don’t even text “stop.” Any kind of communication tells the scammer that your phone number is active—and ripe for targeting again. Your best bet is to block the number. “Users should also report all spam texts to their wireless carrier for them to investigate,” says Prejean. (Here are 10 online scams to be aware of—and how to avoid them.)

What should you do if you clicked a scam link?

Everyone makes mistakes. If you think you’ve already clicked a fraudulent link and/or provided compromising information, take immediate action. First, change all of the passwords that are associated with the information you gave out. Next, contact the real company you thought you were texting to let them know what happened. Also, make sure to run a malware check on your phone to ensure the link didn’t allow malicious code to be downloaded on your phone. Two good malware removal apps are Malwarebytes and Avast Antivirus.

Most importantly, if you gave out bank or credit card information, contact the bank or credit card company to report suspected fraud and cancel the card associated with the account.

Next, find out more ways to stop spam texts on an iPhone or Android.

Apple is known for its nearly impenetrable security. But no system is fail-safe. Even Apple devices and users sometimes become victims of hackers and iPhones can get viruses. One of the most common ways is through a scam known as Apple ID phishing. In fact, phishing accounted for about a third of all data breaches in 2019, and 10 percent involved attempts to steal someone’s Apple ID or password.

What is an Apple ID phishing scam?

Phishing is a scheme in which hackers try to trick you into divulging personal information, such as passwords and Social Security numbers. They accomplish this by sending emails, texts, and other types of messages that look like they’re coming from a legitimate company, like Amazon, your bank, or your email provider. These messages typically have a link that, when clicked, takes you to a spoofed website, where your data may be stolen.

In an Apple ID phishing scam, hackers are specifically trying to get you to give up your Apple ID and password. Apple requires user IDs and passwords to access Apple services like the App Store, Apple Music, iCloud, iMessage, and FaceTime. Says Russel Kent-Payne, director and co-founder of Certo Software, “If configured correctly, iPhones can be quite secure, so sometimes phishing is the only option for hackers.” (Watch out for the four things hackers can do with your cell phone number.)

Why would someone phish for your Apple ID?

Your Apple ID account contains all your contact, payment, and security information. If hackers discern your ID and password, they can dig even deeper, gaining private information either for their own nefarious uses or to sell on the black market. “The bad guys get access to your iCloud email, and the history of your app, music, and movie purchases and rentals,” says Chris Hauk, consumer privacy champion at Pixel Privacy. They also have entry to all your documents, photos, and files stored on your iCloud drive. They can even use your account to watch your movies. (Learn why Apple execs say you’re using your iPhone wrong.)

How do Apple ID scams work?

Scammers have become very savvy and will use any method available to them to get your attention and try to phish for your information. Hauk says spoofed emails and texts are the most common methods. “They’re the easiest to pull off and don’t require any real programming skills on the part of the bad actor.”

But scammers will also target you through browser pop-up notices, phone calls, and even calendar invitations. Usually, they try to entice you to click on a link or call a phone number for legitimate-sounding purposes but are actually trying to either steal or get you to divulge personal information. Often, scammers create a sense of urgency, says Kent-Payne, “so that their victims react quickly to the message and are then less likely to spot that it’s a fake.”

What are the main Apple ID phishing scams to be aware of?

Hackers are continually inventing new scams but some of the most enduring ones include the following:

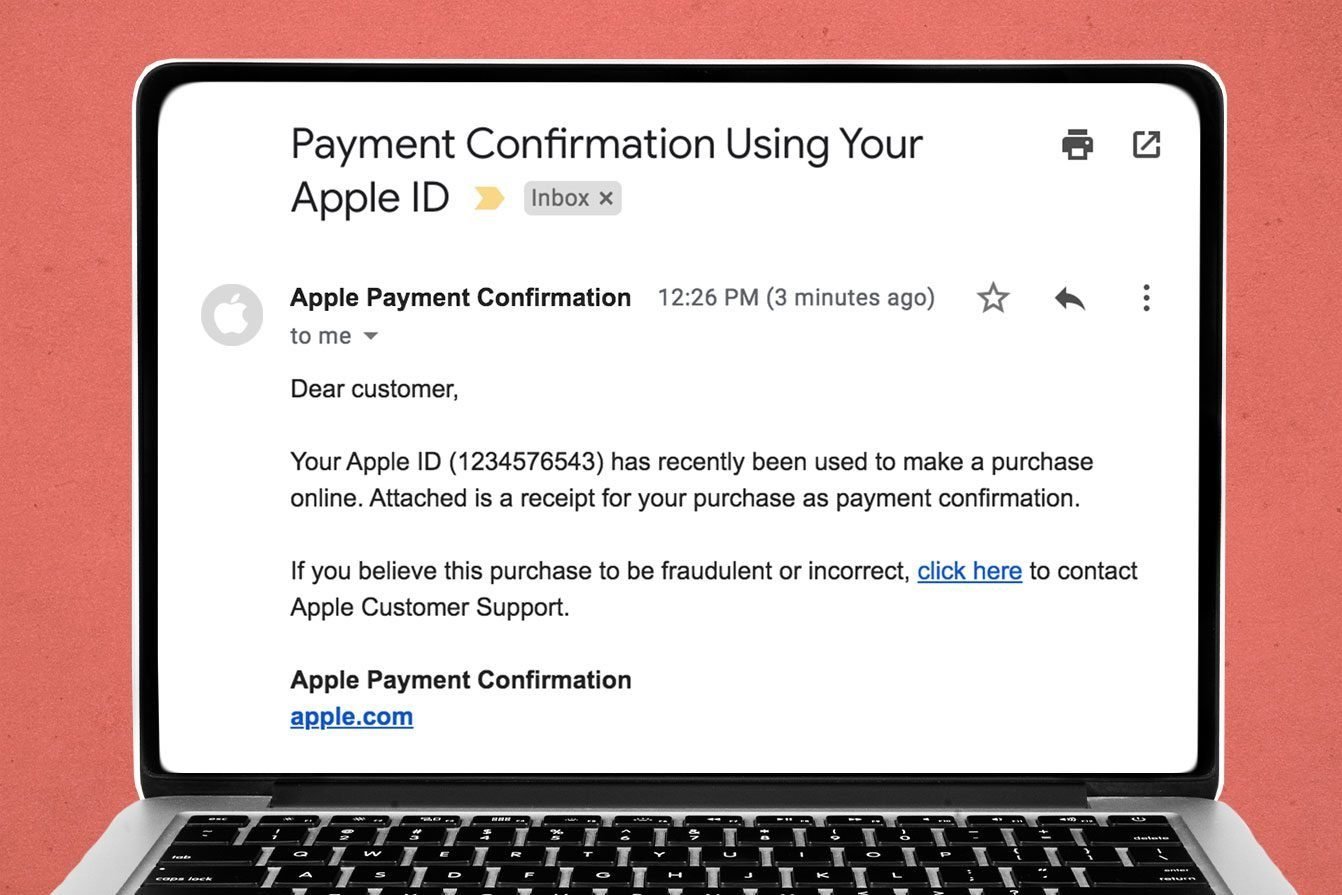

Apple ID order receipt

In this type of scam, you’ll receive an email that appears to be from Apple, stating that your ID has been used to make a purchase, usually with a PDF receipt attached as “proof.” The email will either ask you to confirm the purchase or submit payment for it. In either instance, there are typically links that, if clicked, will take you to a fake Apple account management page. “It attempts to entice you to give up your Apple ID and password,” Hauk says.

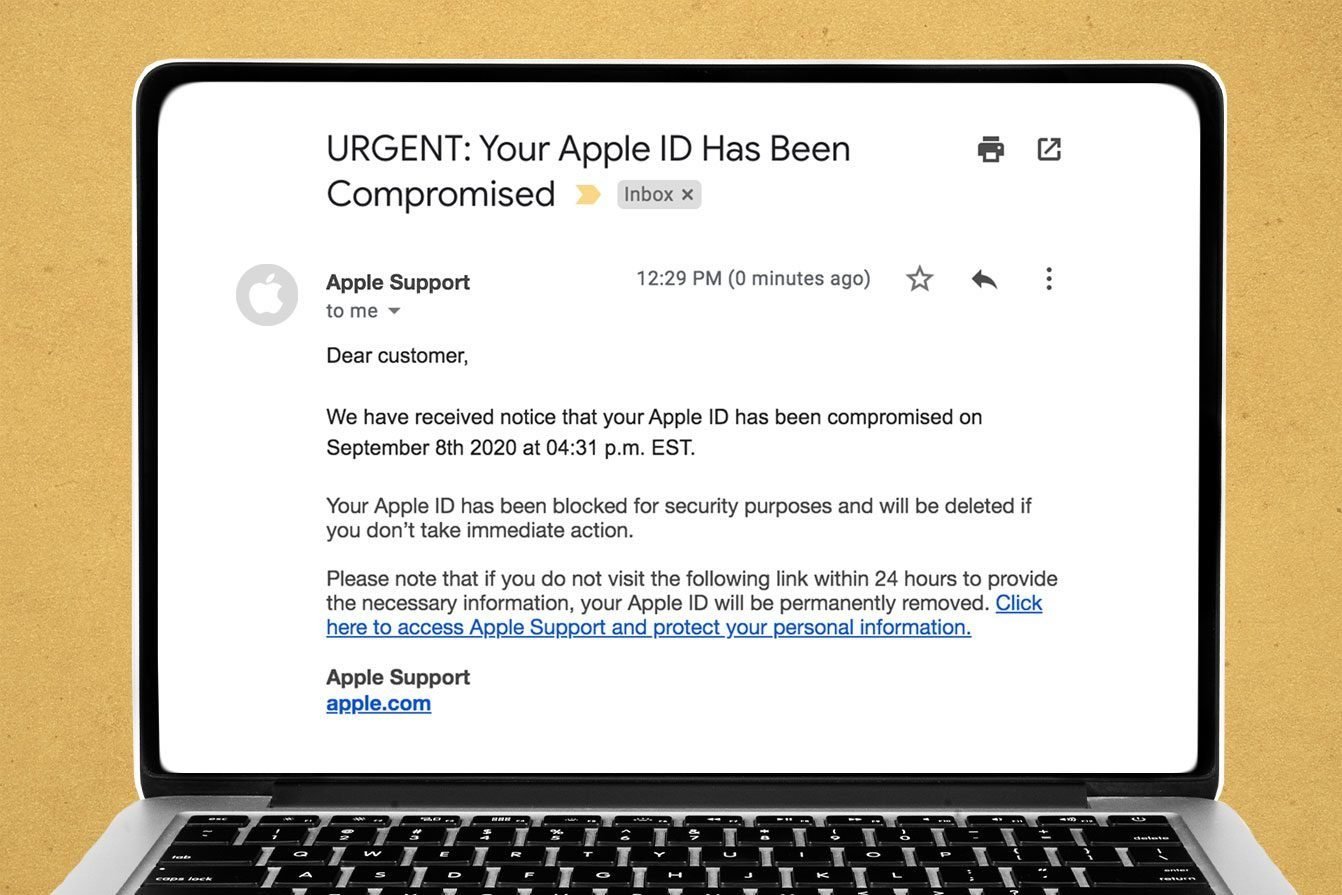

Apple ID locked

This scam often works in tandem with the fake receipt scam. If you do follow a spoofed email to a fake Apple page, and then input your information, you may see a notification telling you that your account has been locked due to suspicious activity. Then, it will show you an “unlock” button, which requires you to divulge personally identifying information, such as your name, Social Security number, payment information, and answers to common security questions. Sometimes, this scam will arrive via an iMessage alert stating that your Apple ID has been locked because your ID is about to expire. The message might ask you to complete a form to unlock your account, which of course gives the hackers access to sensitive info. It’s true that Apple IDs sometimes are locked if Apple suspects fraudulent activity, but they can be unlocked with a phone call that you place directly to Apple. However, Apple IDs don’t expire, Kent-Payne says. (Don’t miss the 20 cybersecurity secrets hackers don’t want you to know.)

Apple support scam

In this scam, you usually receive a phone call—or often, several calls in less than an hour— from what appears to be the real Apple support phone number, but instead the number has been spoofed. If you answer the call, the scammer claims to be from Apple and says your account or Apple ID has been compromised; to fix things for you, they’ll say, they need your password or other sensitive information. Sometimes, rather than speaking with you directly, scammers will leave an automated voice message directing you to call a specific number for “Apple support.” If you call the number, everything sounds legitimate, including updates telling you the anticipated hold time. When you finally connect with a human, they will ask you for compromising information. For the record, Apple will never call you to notify you of suspicious activity. In fact, Apple won’t call you for any reason—unless you request a call first. Phone scams like these are also known as vishing.

iPhone locked

If you get hit with this scam, you’ve probably already fallen for at least one other Apple ID scam. If hackers have already gained access to your iCloud account, they could activate the “Find My iPhone” feature and place your device into “lost” mode, which remotely locks it. Then you’ll see a pop-up message on your phone saying that it will remain locked until you pay a ransom.

Calendar invitation

You might receive a spammy iCloud calendar invitation to a meeting or event from an unknown individual or group, often with promises for easy money, pornography, or pharmaceuticals. You guessed it: If you click on a link or respond to the invitation in any way, you’re opening yourself up to phishing or, at the very least, more spam. (Here are the times you should never “accept cookies” on a site.)

How to spot Apple ID phishing scams

Scammers are becoming increasingly sophisticated in the art of making emails, texts, and other communications look like the real deal. “Being able to recognize an attack is key to protecting yourself against phishing,” says Kent-Payne. Here’s what to look for.

- Spoofed address. Hover on the sender’s name in your inbox to see the full email address. If the message claims to be from Apple but the address is off by a letter or two—or worse, is just a bunch of random letters and numbers—it’s probably a phishing attempt.

- Vague greeting. Reputable companies will usually address you by your full name, says Kent-Payne. Scammers will use something more generic, like “dear friend.”

- Misspellings, grammar mistakes, and obvious typos. Reputable companies take pains to make sure their communication is clear, accurate, and precise.

- A sense of urgency. Phishing scams often create a false sense of urgency or rely on emotional manipulation to get you to act quickly.

Any legitimate email related to your Apple ID account will always come from [email protected]. In addition, emails from Apple will never ask you to disclose your Apple ID password, Social Security number, your mother’s maiden name, your full credit card number, or your credit or debit card’s CCV security code. (Watch out for these online scams to be aware of—and how to avoid them.)

How to protect yourself from Apple ID phishing scams

The best way to avoid becoming the victim of a phishing attack is to never click on a link or attachment within an email, text message, or pop-up unless you’re 100 percent certain the message is real.

The same holds true for phone calls. Apple and other companies will never call you out of the blue to discuss your device’s security. Don’t accept these calls or click on hyperlinked phone numbers within messages.

In addition to ignoring unsolicited communication, Kent-Payne suggests enabling two-factor authentication for any important accounts, including Apple ID, email, social media, and banking. “This means that even if a hacker works out your password via a phishing attack, they still can’t access your account,” he says. (Here are the password mistakes that hackers hope you’ll make.)

He also recommends using Apple’s Message Filtering. That feature separates out any texts you receive from people who are not in your contacts and sends them to the “unknown senders” tab in your Messages list. You can turn on message filtering in Settings. If you use filtering in conjunction with a good security app, such as Truecaller or SpamHound, the app can alert you when you receive a phishing message, Kent-Payne says.

Also, be sure to adhere to the following best practices:

- Never share your Apple ID password with anyone, including someone who says they’re from Apple.

- Keep your operating system updated to the latest version.

- Keep your browsers updated. Also consider using a browser like Chrome, which has built-in phishing protections.

- Use antivirus and anti-malware programs on your devices.

- Always check the URL of any website where you’re entering sensitive information. It should always start with “https” (the “s” stands for “secure”).

- Don’t reuse the same password on multiple sites. That just makes it easier for hackers.

What should you do if you receive an Apple ID phishing attempt?

In most cases, you can safely close and ignore the email, text, or pop-up, or hang up on the caller. Whatever you do, don’t click on any links or provide any personal information to the scammer. You should, however, report the attempt to the appropriate parties.

If you receive a suspicious iMessage or calendar invite, you should have an option under the message to “Report Junk.” If the option doesn’t appear, you can still block the sender. And if you get a fake tech-support phone call, you can report it to your local police department.

And if you do happen to accidentally click on a suspicious link, don’t panic. “As long as you don’t supply any information that might be requested on a linked webpage, you should be okay,” Hauk says. If you did enter personal information, you should immediately change your Apple ID password and enable two-factor authentication. Then review all the security information in your account to make sure it’s still accurate. This can include your name, your primary Apple ID email address and any other rescue emails or phone numbers, and your security questions and answers. You should also check to see where your Apple ID is being used. You can find that information by going to Settings, and then clicking on your name. If you see a device you don’t recognize, you can remove it from the list.

Next, learn how to stop spam texts on an iPhone or Android.

Me and My Chosen Family

In 2012, I came out as trans to my close friends. I was 21 years old, had moved to Montreal three years prior and was forging my own identity as an adult. At the same time, my relationship with my family was growing strained—our values and our beliefs about our Muslim faith didn’t always align. In 2017, I cut ties with most of my relatives.

Around December I would often miss one of my favourite Ismaili Muslim traditions. Ismailism is a sect of Shia Islam—there are about 80,000 of us in Canada—and every year on December 13, my community would gather in a high school cafeteria close to our mosque to celebrate Salgirah Khushali, the Aga Khan’s birthday. After prayers, we put on a big, flamboyant show. People performed Bollywood dances, comedy skits, even lip-synchs to Top 40 songs. In fact, the first time I ever saw someone in drag was when, on this holiday, a girl dressed as a boy for a rendition of TLC’s “No Scrubs.”

Two years ago, I realized I didn’t have to give up this tradition and decided to celebrate with my chosen family—four friends and my girlfriend, all of whom I met at university. They’re not Ismaili, but on December 13, we make a playlist of Bollywood and Christmas songs that we blast while we decorate a tree at my apartment. Then my girlfriend and I pose for a photo shoot—one that includes our terrier mix, Katya, dressed in a Santa hat.

Now that I know I can be both trans and Muslim, I can’t wait for COVID-19 to pass so that I can go back to mosque—this time worshipping on the men’s side.

Next, learn about how a house party inspired a support network for trans women.