We’re back at it again with the TikTok hacks! From making your pots and pans look brand new to a brilliant ketchup bottle hack, it seems the viral video social media site just has it all.

The latest video making it into the coveted TikTok hack party requires only your favourite wine glass and some cake. Yes, you heard that correctly—it’s time to learn the perfect cake cutting hack! We’ll never cut a cake the same again.

What exactly is the cake cutting hack?

It’s actually so simple that we’re kicking ourselves for not thinking of it earlier. Imagine it’s your birthday, and you’re together with a few of your best friends for a (socially distanced) fun night in of wine and lively conversation. You’ve got a gorgeous red velvet cake to commemorate the event and are about to start slicing when….you realize there’s a much easier way.

@theroseperiodHappy 20th birthday to my Jules!##twenty##fyp##birthdaycake##wineglasses##tiktokmom♬ Outro: Happy Birthday – Altered Images

Introducing the cake cutting hack we didn’t know we needed. What you’ll do is take a wine glass, flip it upside down and press it into the outer rim of the cake. As the glass slides down, a good chunk of cake will separate into your flipped wine glass (depending on how much you chose to take). After that, all you have to do is flip your wine glass right side up, grab a fork and dig in!

Cut smarter, not harder

Just think of all the dishes you save with this trick. That’s honestly my favourite part of the whole thing! It’s fun to try new and odd things every once in a while, you know? This trick has been showing up in a few different places other than TikTok, too, like Twitter and the like. I guess this gives me the perfect random reason to bake a cake this weekend then, right?

Next, check out how to make powdered sugar in seconds.

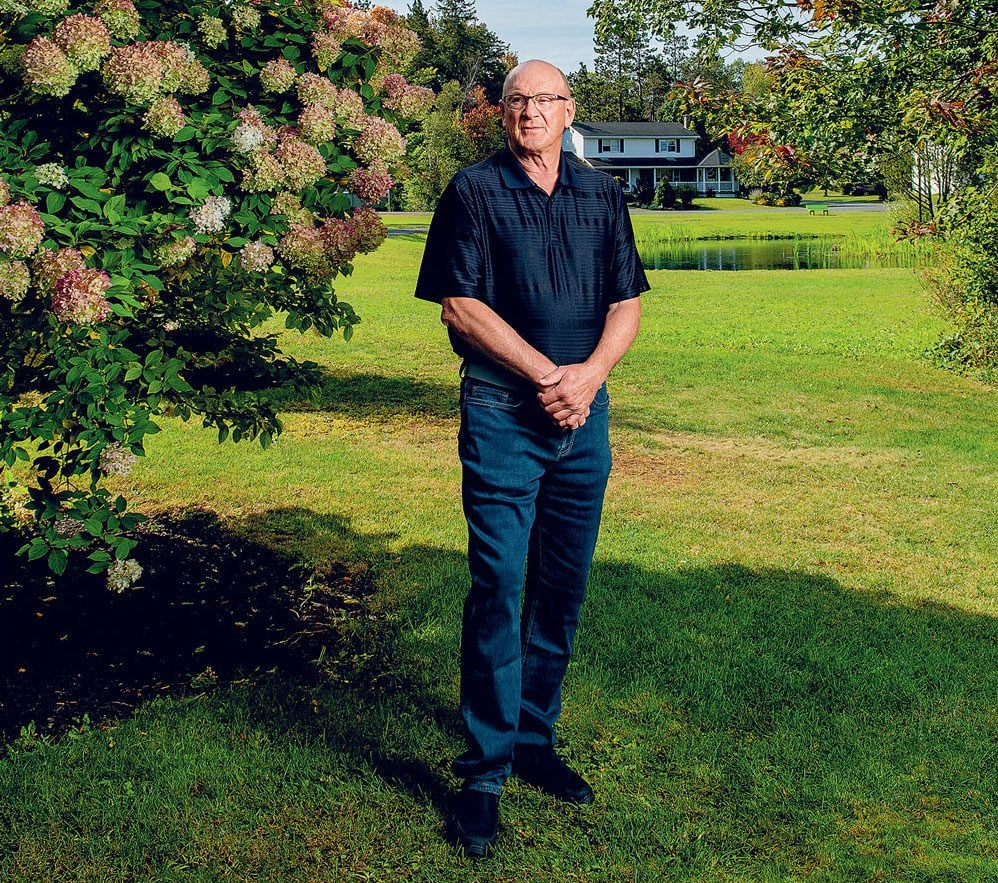

Rick Cameron was tired. His body ached, and his breath seemed to catch in his chest—a bout of the flu, he assumed, something he’d picked up from the grandkids who’d been clambering over him the week before.

It was Friday, March 13, and in Stellarton, Nova Scotia, the coronavirus still felt like a distant threat. It was an item on the news, not something that could plausibly find its way to this sleepy maritime town.

At 69 years old, Rick was healthy and strong, a six-foot-two former athlete who had spent decades coaching youth hockey. He’d grown up in a tiny village on the coast and spent 41 years at the Michelin tire plant in Pictou County, working his way up from forklift driver to industrial engineer to business analyst. He’d met his wife, Faye, when he was 17 and she was 15. Rick was blond and outgoing and “pretty hunky,” Faye remembers. On Saturdays, after helping his dad on the lobster boat, he’d pick her up in his prized Ford Falcon and drive to dance night at the local rink. They married four years later. It was a relationship, their daughter Kelly used to complain, that was so impossibly conflict-free that it had ruined her conception of what a marriage should be.

Kelly, a 40-year-old manager at Money Mart, had never really worried about her dad. He’d always been the one to take care of her and her brother Jeff, helping her through her battles with depression as an adult, bringing his insistently positive attitude to the worst situations. After a house fire a few years ago, she and her 44-year-old husband, Brian, had moved into her parents’ three-bedroom Cape Cod–style home in Stellarton. The four of them have lived together ever since.

That weekend, with her dad already self-quarantining in the basement, Kelly stood at the top of the stairs and listened with growing concern as Rick weathered coughing fits that seemed to shake his entire body. On Monday, Rick and Faye drove 40 minutes to the ER in Truro. Masked health-care workers examined him and asked him if he’d been out of the country recently. He told them he’d vacationed in Florida for two weeks in mid-February, but that was nearly a month earlier, well past COVID’s two-week incubation period. The hospital said it was only a viral infection and released Rick, telling him to take some Tylenol and get some rest.

As the week went on, however, Rick got worse. By Wednesday, he was so weak he could barely move. By Thursday morning, he struggled to breathe. “I think you better call an ambulance,” he told Faye. To reduce the possible spread of the virus, family members weren’t allowed in hospitals. As the ambulance was leaving, Faye rushed out to give her husband his phone and say goodbye.

At the hospital in New Glasgow, doctors swabbed him for COVID before transferring him to Truro, where doctors had created a COVID unit in anticipation of a possible epidemic. That evening, doctors called Faye to tell her the news: her husband had tested positive for COVID-19. They weren’t sure where he’d caught it—possibly in the community, possibly from someone else who had returned from the States. “What do I do now?” Faye asked. “Pray,” said the doctor.

That night, so weak he could barely work the phone, Rick called his wife. “Don’t get upset,” he said. If she started crying, he knew he’d start too. The doctors had a plan, he assured her. Before he said goodbye, he apologized for putting her through all this. He told her he loved her. When Faye called the next morning, the hospital told her Rick had been intubated and put into a coma late that night.

Coma

The eight-bed ICU at the Colchester East Hants Health Centre in Truro—a town with a population of about 12,000—is not often at the forefront of modern medicine. When Rick Cameron arrived on March 20, however, the hospital became home to the first critically ill COVID patient in the province.

The man in charge of his care was Dr. Kris Srivatsa, a 44-year-old internal medicine specialist with an easy smile and a swoosh of salt-and-pepper hair. Srivatsa had ended up in Truro almost by accident. Born in Mumbai, Srivatsa had relocated to the U.S. to finish his medical training. In 2009, with his visa running out, he’d desperately Googled “job opportunities in Canada” and stumbled upon a posting from a Nova Scotia town he’d never heard of.

Just a few months later he found himself driving deeper and deeper into what felt like uninhabited wilderness, second guessing his decision. But Srivatsa found an unlikely home in the community. He’d met his husband, an artist and gallerist, and they spent their vacations hiking Cape Breton Island. “It felt like a homecoming,” he says today. In 2015, he became a citizen.

In late February, as the mysterious new virus made its way across the globe, Srivatsa and his team began anxious preparations—creating a COVID unit, securing personal protective equipment and practising procedures.

The process of intubation—sedating a patient before inserting a nearly foot-long plastic tube down their windpipe—is a routine part of ICU treatment, but it had suddenly become perilous in the COVID era. There is a high risk of aerosolizing a patient’s saliva and respiratory secretions from their lungs and airways, sending the virus airborne. Srivatsa had been following the stories of nurses and doctors in Italy becoming infected and dying. He was determined not to see that happen in his hospital.

Rick had been immediately put on oxygen through a nasal cannula, a tube to his nose. But it wasn’t enough. He needed more than five litres of oxygen every minute to keep his blood oxygen levels above 90 per cent. His lungs simply weren’t drawing in enough air—he had to be intubated.

That night, the team in Truro carefully donned their personal protective equipment. Using the buddy system, team members watched each other put on gowns and gloves, N95 masks, face shields and hats until they were sweating beneath their armour. They sedated Rick, putting him into a coma. Then the anaesthetist approached. The key was to do it in one shot—any more attempts and you increase the risk of aerosolization.

The procedure went perfectly on the first try, and the team quickly worked to stabilize Rick. But the truth was, Srivatsa didn’t know how to treat his COVID patient. No one did. There is no cure for COVID-19. The most doctors can do is keep a patient alive and wait for the body to fight off the virus. Srivatsa and his colleagues were learning about the virus in real time alongside the rest of the world.

Srivatsa spent his evenings poring over the latest studies, reading about what had worked in other countries, looking for any clue that might improve the likelihood of Rick’s survival. A machine can do the work of breathing for a person for a little while. But at that point, early in the pandemic, the survival rate for people on ventilators was grim: up to 90 per cent of COVID patients on ventilators were reported to have died. (Later studies found that those early reports that Srivatsa had read were misleading, with the mortality rate more likely to be in the 30 to 50 per cent range.)

A Big Decision

In the days after Rick was diagnosed, Faye, Kelly and Brian each received their own positive COVID tests. The house became a divided sick ward. Faye was in the basement, suffering through her own chest congestion and fever, but thinking only of her husband. Each day was the same: she would wake up, sit in one little corner of the basement, and call the hospital. Then she’d sit and wait until it felt like a reasonable amount of time had passed before calling again.

With her dad unconscious in the ICU, Kelly started a Facebook page to let friends and family members know what was going on. It was a place for her to record their days—a diary she vowed her dad would read himself once he recovered. It was also a way to try to feel close to him at a time when COVID had forced families like hers apart, with hospitals still closed to visitors.

For Kelly and Faye, not being able to see Rick was the hardest part. For Srivatsa, too, having to share important news over the phone felt cruel and impersonal.

“Do you have access to Skype or some way that I can video call you?” he asked Faye one day. The doctor started a video call on his phone, and for the first time in weeks Faye was able to see her husband. “That was a turning point for me,” she says. She was able to put a face to the voices of all of the nurses and doctors who had been caring for him. And she could finally picture where her husband was—not in some strange void in the ether, but lying in a hospital bed, unconscious and shockingly thin, but still fighting, still her Rick.

After that, the family worked out a system with the nurses. They would do video calls with an iPad. Often a nurse would leave a phone on the pillow in Rick’s room for hours. Faye would tell him they loved him and say how well he was doing, even if the news that day had been bad. When she ran out of things to say, she would sing—songs by the Righteous Brothers and the Beach Boys, all the old classics she and Rick had listened to a lifetime ago, driving out to the rink in his Ford Falcon.

By week three, however, Rick was still in a medically induced coma, still testing positive for COVID. Srivatsa and his team adjusted his sedation. They tweaked the setting on his ventilator. But Srivatsa was getting worried. Rick’s body’s response to the illness had caused widespread inflammation. His creatinine levels were up, indicating a kidney problem. In a growing number of cases, those symptoms led to one outcome. “My goodness,” Srivatsa thought to himself one day. “After all this, he’s not going to make it.”

The doctors needed to get Rick’s lungs working. One way to do that was to put him in a prone position, turning him onto his stomach for a few hours before turning him back so that the back of the lungs, which had been compressed by the weight of his body, would be able to do their work.

Proning a grown man attached to a series of tubes and lines is a delicate, complex manoeuvre that takes a team of nine. Truro didn’t do the procedure in normal times; they sent patients to the larger hospital with more staff in Halifax. But these weren’t normal times. The move also came with serious risks: if something went wrong and Rick was destabilized and went into cardiac arrest, doctors might not be able to turn him back in time to save him.

When doctors told Faye she needed to decide if they should do the procedure, she burst into tears. That day, Faye and Kelly sat at either end of their large living room with Kelly’s brother Jeff on the phone, and talked through their decision. Suffering through the worst of her own illness, Kelly would fall asleep, then wake in a panic. Faye decided she couldn’t agree to anything that might endanger her husband. But that night, she couldn’t sleep. “What if I didn’t do the right thing?” she kept thinking. The next morning, she gave doctors the okay.

On April 3, Srivatsa and his team carefully followed the steps they had learned over video from doctors in Halifax. With three nurses on each side of his body, two respiratory therapists attending to the lines and ventilator at his head, and a doctor at his feet, the team turned Rick. Then they waited. Just a few hours later, the improvement was already evident: Rick’s oxygen levels were ticking up. He was finally beginning to turn the corner.

Sharing Progress

When Kelly started documenting her father’s battle with COVID, she just wanted to share his progress. But what had begun as a family page quickly grew into something much larger. The “papa bear” Kelly wrote about so movingly day after day became the face of an illness that was no longer a distant story. The local news covered Rick’s journey. Kelly’s posts were read by thousands, each message gathering hundreds of comments from people across the province and the continent.

On Easter Sunday, 25 days after Rick was hospitalized and nine days after the medical team first rotated him into a prone position, nurses called Kelly and Faye, excited to share some news: that morning, Rick had opened his eyes. They got Rick on the iPad, and there he was—still with tubes all over him, still so weak and fighting the sedation, but awake.

There were ups and downs, but steadily Rick grew better. Each day doctors put him into a prone position for a few hours. Each day they reduced the amount of oxygen on the ventilator, watching as his lungs became less and less dependent on the machine. The day they removed his tracheostomy tube, the nurses huddled around him. “Say something!” they urged. “Hi,” Rick croaked.

On April 26, 38 days after entering the hospital, Rick tested negative for COVID. A few days later, he was moved to the hospital in New Glasgow to start the long process of recovery. One morning he looked at his hand and felt a wave of terror as he realized he was too weak to raise it off the bed. He spoke to Faye and Kelly over the iPad, trying to make sense of what had happened to him. “How long have I been in here?” he asked.

Rick had been on life support for 35 days and had lost 45 pounds. But as his mind grew sharper, he became determined to get stronger. When the physical therapist asked him to do three minutes on a stepping machine, the next day he would do six. He became singularly focused on one goal: getting strong enough to get home to his family.

Srivatsa was no longer in charge of Rick’s care, but he couldn’t help but follow his former patient’s progress from a distance. “He felt like a family member,” says Srivatsa. When someone sent him a video of Rick doing physiotherapy, Srivatsa could scarcely believe it. Just three weeks earlier Rick had been comatose and intubated, a team of nine turning him onto his stomach. Now he was walking, shaky but determined, wearing a maroon hoodie emblazoned with the words “FU COVID.”

Home at Last

On June 3, Kelly’s 40th birthday and 77 days after Rick first entered the hospital, the family was finally able to bring him home. It was a cold and rainy day. When they arrived at the hospital, Rick was clutching a cane and wearing the same shorts in which he had first arrived. “He pretty near ran to the car,” says Faye. Rick hugged his wife. “Happy birthday, honey,” he whispered to Kelly, and they both burst into tears. As they pulled out of the parking lot, they gave a final wave to the nurses who were waiting by the entrance with tears in their eyes.

After two and a half months, the world outside the hospital walls seemed utterly transformed to Rick. People wore masks on the streets; “social distancing” and “flattening the curve” had become part of the lexicon; stickers marked where to stand at the local grocery store. It was a world in which an undercurrent of anxiety ran through the most basic human interactions. But in that corner of Nova Scotia, the pandemic had also brought people together.

As they turned onto the Camerons’ quiet street, Rick saw a strange sight: a woman he didn’t know on her front lawn, standing under an umbrella in the pouring rain, waving at him. Before he could make sense of it, the car pulled into the driveway, and he saw 40 people—neighbours and friends and complete strangers—surrounding his house, waving and cheering him on like a conquering hero.

In the weeks and months since he’s been home, Rick is still trying to make sense of his experience. Each day he walks around the pond near their house, adding laps, gaining strength. He’s only recently been able to make it through Kelly’s Facebook posts, fighting back tears as he read the thousands of comments and prayers. It was strange to think about. If you added it up, all the people he’d met in his seven decades in that corner of Nova Scotia—the kids he’d coached, the co-workers he’d had a beer with, the countless hellos and pleasantries he’d shared in his personable way—Rick might have said he knew thousands. But to see all those people supporting him, willing him on, taking his personal survival as a symbol of hope in a dark time, that was almost too much to take in.

“I can’t walk up the street without cars stopping to talk,” he says. The other day a woman approached him at the local fish and chips place. “I know who you are,” she told him. She had been following his story for months. He was the man who’d seen the worst of COVID, nearly died, and walked out the door of the hospital.

Next, find out what it’s like to have a baby during the COVID-19 lockdown.

My first note

Last February, before the world went into lockdown, I sat in a cramped waiting room with about 10 other people, all under age 12. “I’m dyyying!!” I texted my friend, shaking with silent laughter. “What am I doing here?!”

Here was a music academy, and I was about to take my first trumpet lesson. Learning to play was something I had talked about for years, for no reason other than I thought it would be fun. But it wasn’t until my husband gave me a trumpet for Christmas that I got the final push to give it a try.

I was floundering. In three years I’d had two kids, left a full-time job to freelance, and we’d moved across the country. I wanted something that was invigorating, a little out of left field and, most importantly, just for me.

I’ve never mastered a musical instrument before and had lived with the quiet shame of being called tone deaf since I was a kid (I’m not, for the record). But there I was at 42, throwing my lot in with a bunch of preteen mini Mozarts. I was simultaneously nervous and thrilled by the idea of starting something new.

It had been years since I’d tried a hobby in which I had no background, no connections, no baseline knowledge. I was curious to see if I could hack it. As it turned out, I could—and with a few simple tips, so can anyone.

Embrace discomfort and have fun

As adults, we’re reluctant to go outside of our comfort zones. We may fear looking foolish or making mistakes. But there are advantages to being an adult learner. If you’ve chosen to explore a hobby, it’s because you genuinely want to. You’re motivated to learn. And you bring a wealth of experience that you can connect with to help learn new material.

“The wonderful thing about being older is that you have more time and opportunity to try new things,” says Dr. Marnin Heisel, a clinical psychologist and professor at Western University whose research focuses on psychological resiliency and well-being among older adults. It’s easier to convince yourself to cut loose and have fun. “Some people step back, take a look and say, ‘My life isn’t as fun or fulfilling or meaningful as it could be. And the main thing stopping me is me.’”

If you’re stuck on what to do or where to start, Heisel suggests a simple technique: adult show and tell. It’s easy. Imagine you had to present a meaningful or sentimental object to a group of strangers that tells them something about your story or your personality. Consider why you love it. Then ask, what sort of fulfilling pastime can I build around it? You’re more likely to dive into a new activity if you already have a positive association with it.

There are physical benefits, of course, to choosing hobbies and activities that get you moving, and physical activity, in turn, has beneficial effects on executive functions and memory. Most crucially, chasing hobbies that offer positive and meaningful experiences makes us happier and could also make us more adaptable to the inevitable changes in life, says Heisel. “When we look ahead to the future,” he adds, “most of us are also concerned with life satisfaction and enjoyment, not just warding off cognitive impairment, as important as that may be.” (Learn about the surprising benefits of stress-baking.)

Go with the flow

Once you find a hobby that you happily look forward to doing, more benefits will come—especially if you tap into “the flow.” That’s the term coined by prominent psychologist and author Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi to describe when you’re fully immersed in a challenging, absorbing activity—time flies, self-consciousness disappears and the world around you melts away.

Sixty-six year old Rob Doggett recognizes that flow every time he climbs on his Suzuki dual-sport motorcycle. “Being on the road, it’s exhilarating,” he says. “The wind whistles in my helmet, and I’m laser-focused on everything around me. There’s no time for daydreaming. It tests everything: attention to detail, alertness, mental stamina.”

Doggett, a retired restaurant owner, learned to ride when he was in his mid-50s. He’d always been drawn to motorcycles but wasn’t comfortable taking on the risk of riding until his three children were grown. It’s now part of a collection of activities—golf, curling, umpiring rec-league baseball, handiwork—that he does to stay active in retirement. “The more active I am, the more reason I have to get out of bed in the morning,” says Doggett. “It keeps me young.” (Check out these 40+ secrets to a happier life.)

Make a connection, and don’t give up

If new hobbies don’t in and of themselves have a social element, it often doesn’t take much to make them social, says Heisel—and it can help to keep you invested and having fun. If you want to learn to paint, learn to paint with other people. If you want to garden, get to know the horticulturist at your local garden centre. If finding a physical community is too challenging (and these days it can be), go online, find a group, build social connections and try new things, all while staying comfortably close to home.

Here’s how it works for me: I now take trumpet lessons over Zoom, which holds me to playing at least once a week (I’m accountable); my teacher is an impossibly patient and lovely person (I feel supported); when I started in February, I promised my son that I’d learn to play “Happy Birthday” for when he turned three in May (I gave myself a goal and a deadline); and I even participated in an online summer recital (I connected with a new community, under pandemic conditions no less).

I know playing trumpet won’t solve my existential middle-aged-mom crisis, but it’s loud and it’s fun and I like that I can toot-toot my way through a “Happy Birthday” serenade for special people. Plus, I’m investing in future fulfillment, a more balanced life and long-term fine-tuning for my brain, which all feels pretty great.

Next, here’s how to take better care of yourself during the pandemic.

A silent killer

High blood pressure produces no signs, and yet it can dramatically increase the risk for heart attack and stroke. No wonder it’s often called the silent killer.

When blood pressure creeps up so high that it causes potentially life-threatening symptoms, it may be a type of high blood pressure crisis known as a hypertensive emergency, says Stephen J. Huot, MD, PhD, professor, associate dean, and director of graduate medical education at Yale School of Medicine/Yale New Haven Hospital.

Not surprisingly, it can warrant a 911 call or a trip to the emergency room.

What is a high blood pressure emergency?

The answer can be found in two numbers. Systolic blood pressure, the upper number in a blood pressure measurement, refers to how much pressure your blood is exerting against your artery walls when the heart beats. Diastolic blood pressure, the lower number, indicates how much pressure your blood is exerting against your artery walls when the heart is resting between beats. A blood pressure of less than 120/80 mm Hg is considered normal. (Check out the surprising things that affect your blood pressure reading.)

If your blood pressure is 180/120 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) or higher and you have chest pain, back pain, numbness or weakness, or a change in vision, you may be experiencing a hypertensive emergency.

These symptoms suggest you may be experiencing what’s called end-organ damage, Dr. Huot says. “Untreated high blood pressure negatively impacts blood vessels in critical areas of the body such as the brain, heart, kidneys, and the aorta, which is the main blood vessel that carries blood away from your heart to the rest of your body.” (Learn the 10 risk factors for heart disease and how to control them.)

End-organ damage takes many forms including stroke, heart attack, and kidney failure. It’s not just the blood pressure numbers that indicate the emergency and risk, it’s the symptoms of end-organ damage, he says.

Other signs of end-organ damage due to a high blood pressure emergency can be:

- Passing out

- Memory loss

- Damage to the eyes

- Rupture of the aorta, the body’s main artery

- Crushing chest pain (angina)

- Fluid build-up in the lungs

- Preeclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication

In these emergency situations you need to get help immediately, Dr. Huot says. (Here are the 50+ health symptoms you should never ignore.)

High blood pressure emergencies may also travel with other symptoms that do not indicate end-organ damage—yet. These include:

- Severe headache

- Shortness of breath

- Nosebleeds

- Severe anxiety

Are you at risk for a high blood pressure emergency?

According to Statistics Canada, nearly a quarter of Canadian adults have high blood pressure—meaning, greater than 130/80 mm Hg—or are taking medication to control hypertension, placing them at greater risk for a high blood pressure emergency. (Only about one in four adults with high blood pressure have their condition under control.)

Men are at greater risk than women for a high blood pressure emergency. Other risk factors for a hypertensive emergency include advancing age, diabetes, high blood cholesterol levels, and/or chronic kidney disease, according to research presented at the 2020 meeting of the American Heart Association. Medication interactions may also cause a hypertensive emergency, Dr. Huot explains.

In many instances, these emergencies occur when someone stops taking their blood pressure medication. “Most people who experience a hypertensive emergency have known that they have high blood pressure in the past, but they fall off their medication management wagon and their blood pressure progresses,” Dr. Huot says. “It’s not out of the blue.”

Treating and preventing a high blood pressure emergency

High blood pressure emergencies are treated with intravenous blood pressure-lowering medication and hospitalization, in addition to treating any end-organ damage that has already occurred, says Dr. Huot.

If you experience dangerously high blood pressure along with symptoms that suggest end-organ damage, it is an emergency.

“Start with calling your physician’s office and if you’re unable to reach the doctor, go to the emergency room for immediate evaluation and treatment, ” says Guy L. Mintz, MD, director of cardiovascular health and lipidology at Northwell Health’s Sandra Atlas Bass Heart Hospital in Manhasset, New York. “An ambulance is not required unless the patient feels that they are having a stroke or heart attack, chest pain, or shortness of breath.”

High blood pressure emergencies can be prevented, Dr. Mintz says.

Regular medical check-ups—especially in people with other risk factors—along with home blood pressuring monitoring, at least half an hour of aerobic exercise most days of the week, proper diet with no added salt, and maintaining an ideal weight can all work together to stave off an emergency, he says. (Try these foods that lower blood pressure naturally.)

What is hypertension urgency?

A hypertensive crisis is divided into two camps: urgent and emergency.

In an urgent hypertensive crisis, your blood pressure is extremely high, but there doesn’t seem to be symptoms suggesting damage to your organs. “The distinction is not the level of blood pressure but whether there is evidence of end-organ damage,” says Dr. Mintz.

With hypertensive urgency, your blood pressure is 180/120 or greater. But there is no evidence of end-organ damage—yet. Consider it a really loud warning call, Dr. Huot says.

The American Heart Association suggests waiting about five minutes and taking blood pressure again if your numbers are 180/120 or greater with no symptoms. If the second reading is just as high, check in with your doctor.

“We want to intervene before it progresses to damaged blood vessels and causes an emergency,” Dr. Huot says. Treatment likely entails getting back on medications or starting new ones, he says. “We also do closer follow-up, as opposed to routine follow-up, which we would do if blood pressure is just a little elevated,” he says. There is usually no need for hospitalization with an urgent hypertensive crisis.

Unlike an emergency high blood pressure crisis, those that are considered urgent may travel with other symptoms that do not indicate damage to your organs.

The last word

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for heart attack and stroke. Lifestyle changes such as eating a low-salt diet, maintaining a healthy weight, and getting regular physical activity are often recommended first.

Medication is also available to get your numbers where they need to be. Make sure you know your blood pressure levels and are doing everything that you can to keep them in the safe zone. Even slightly high blood pressure can be dangerous.

Next, find out if blood pressure drugs increase your coronavirus risk.

In 1952, a number of publications (including Reader’s Digest) reported on early evidence linking cigarettes and lung cancer. By 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General declared cigarettes a health hazard, kicking off a downward trend in the smoking rate that continues to this day. Only about 16 per cent of Canadians currently have a habit of lighting up. But because of the long-term effects of smoking, we still face the public health aftermath caused by cigarettes in their heyday, when roughly half the population smoked. One major consequence is the increased prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

What is COPD?

COPD is an umbrella term for chronic diseases that cause shortness of breath, coughing and mucus in the airways.

What causes COPD?

Cigarette smoke is the principal cause in 80 to 90 per cent of COPD cases. Other risk factors include workplace exposure to certain dusts (e.g., inhaling coal or grain residue), childhood respiratory infections and a rare genetic defect that weakens the lungs. These conditions progress slowly, increasingly affecting your breathing over time, and can eventually become fatal. The two most common types of COPD are chronic bronchitis, an inflammation of the lining of the bronchial tubes; and emphysema, which is when the air sacs in the lungs weaken and eventually rupture.

How is COPD diagnosed?

The most reliable way to diagnose COPD is with spirometry, in which a machine gauges lung function.

How prevalent is COPD in Canada?

At last count, there were about 832,100 Canadians with COPD, a number that’s been climbing since the 1950s. It’s currently the country’s fourth leading cause of death, after cancer, heart disease and stroke.

Who faces the greatest risk for COPD?

Women die from COPD at a disproportionately higher rate than men: the number of deaths each year is roughly equal between the genders, even though there have always been fewer female smokers. In recent years, COPD has rivalled breast cancer as a primary threat to the lives of Canadian women. Scientists suspect women are more vulnerable because their lungs are typically smaller and because estrogen may affect the way the body breaks down cigarette smoke, leading to a greater accumulation of toxic metabolites.

What lies ahead?

Studies suggest COPD is underdiagnosed and undertreated. This indifference may be related to the stigma around smoking. But many picked up the habit in their teens, some at a time when cigarette companies were still marketing to impressionable youth. Better public awareness of this disease could prevent more young people from following suit, so it’s worth working to dispel the cloud of shame.

Now that you know the facts about COPD in Canada, find out the signs of lung cancer you might be ignoring.