Mr. Legendary

When Robbie Robertson was a kid growing up in Toronto, his mother, who was born and raised on the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, Ont., often took him back home to visit her family. For Robbie, each trip was like a voyage to another dimension. His relatives had a profound understanding of the natural world and, most important to him, a great love of music. Everyone played an instrument or danced or sang, and Six Nations jam sessions, often held around a roaring campfire, were like small festivals of sound, light and colour.

Something even more transporting—and transformative—happened when he was nine. After lunch one day, Robbie joined a gathering at a longhouse. An elder sat in a large wood chair, draped in animal pelts, and recounted, with vivid imagery and riveting suspense, the tale of the Great Peacemaker who founded the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. Robbie was mesmerized. He told his mother that one day, he was going to tell stories like that.

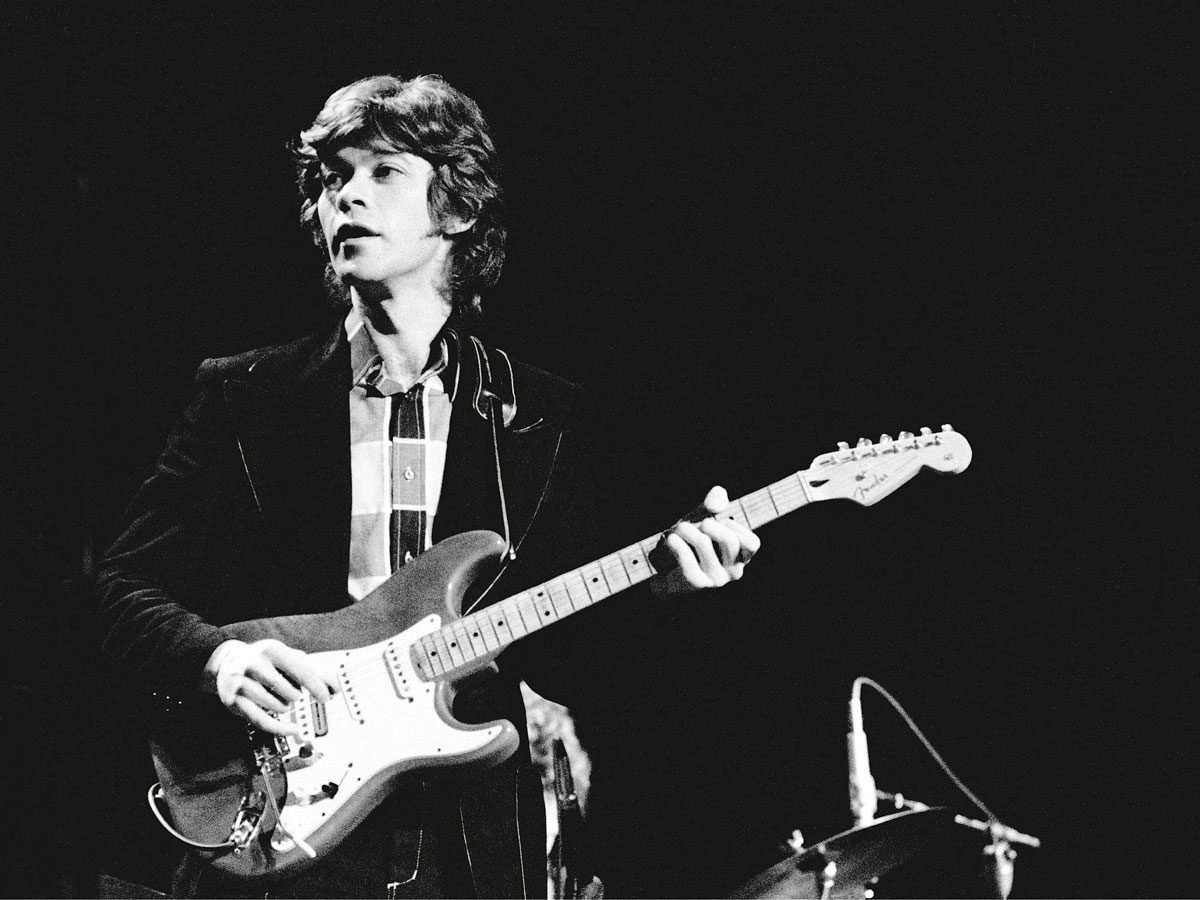

It didn’t take long. Robertson began telling stories—or writing songs, same thing—when he was a teenager, then kept on telling them. There were the gentle puppy-love melodies he wrote for the rockabilly supernova Ronnie Hawkins, then the hits that he later wrote for himself. Robertson’s life story is something else, the story of rock music itself, its ups and downs, its evolutions and revolutions, its undeniable ascent and arguable decline. He is a one-man zeitgeist, a player, both major and minor, in some of popular music’s most defining moments.

He’s still best known, of course, for the groundbreaking songs he created with the Band, the wildly influential roots rock group—songs like “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” The Band was renowned for its industry-defying lack of a front man. Eventually, and enthusiastically, Robertson took on that central role, to the enduring ire of his bandmates. And while his career with the Band lasted only a decade—1968 to 1978—his position as the group’s self-appointed chronicler has lasted about four times as long. Unlike the elder he first encountered as a child, however, the myth he’s recounting now is all his own.

I met Robertson in 2019, the day after a new documentary about him and the group, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. He was tanned and tall and relaxed, his eyes hidden behind signature tinted glasses. Age diminishes us all, even Robbie Robertson, but he’s still ridiculously handsome. In conversation, he is as courteous as a courtesan or as winkingly elusive as his long-time comrade Bob Dylan.

Robertson was born Jaime Royal Robertson; Robbie was a neighbourhood nickname, derived, not so originally, from his last name. His mother, Dolly, was Mohawk and Cayuga, and his biological father, a Jewish man who was killed in a hit and run before Robertson was born, was a professional gambler. He was raised from birth by Dolly and his stepfather, Jim Robertson, a factory worker and war vet. Robertson’s home life wasn’t easy—his parents drank and fought, a lot. Jim would beat up Dolly, then turn his violent attention to his son.

After his relatives at Six Nations introduced him to music, he devoted himself to the guitar, and by 13 he had formed his first band, Robbie Robertson and the Rhythm Chords. Rock and roll had arrived: the radio was alive with Chuck Berry, Elvis, Buddy Holly and Little Richard. Robertson, who describes the discovery of rock as his “personal big bang,” was completely in its thrall. Everything changed: the way he dressed and talked and moved, the way he combed his hair, the way he strummed his Fender. Like it was for millions of teenagers, rock was an escape hatch that could propel him into an unknown future.

For Robertson, rock also looked like it could be a job, one where he could make some money and have a lot of fun doing it. At the time, Toronto seemed like a good place to start. Everyone from future Guess Who guitarist Domenic Troiano to Little Stevie Wonder and the Supremes partied at the city’s raucous clubs.

When Robertson was 15, his band the Suedes was invited to open for Ronnie and the Hawks. It was a revelation. Ronnie Hawkins had Kirk Douglas looks and James Brown moves. He was renowned for his acrobatic stage antics. Robertson had never seen anything like the Hawk, and Hawkins was likewise impressed by Robertson. He told his drummer, Levon Helm, “He’s got so much talent it makes me sick.”

When a spot for a bass player opened up in the Hawks, Robertson dropped out of high school, quickly taught himself the bass, and took a bus down to Arkansas, where Hawkins was currently living, to audition. He knew he was just a kid from Toronto. He worked as hard as he could, which was 10 times harder than everybody else. He learned the set list inside out—the bass and the guitar parts. He rarely slept, and when he did, he slept with his instruments.

“What I was trying to do was impossible,” Robertson told me, still somewhat awed by his own audacity. “I’m 16 years old. I’m too young to play in any of the places they play. I’m too inexperienced to play lead guitar in this group. And there’s no such thing in a Southern rock and roll band as a Canadian. With all these odds, it was impossible. And it was my job to overcome the impossibility. And win.”

He got the job. He won.

Levon Helm quickly became Robertson’s best buddy in the band, the big brother he never had. A few years older, Helm was, in some ways, Robertson’s opposite—short, Southern, hotheaded, with a devilish grin and white-gold hair. As other Hawks left, the rest of the band—Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson—suddenly became Canadian. They were a wild, impossibly talented bunch, and Hawkins worked them hard. They played six days a week and practised all night.

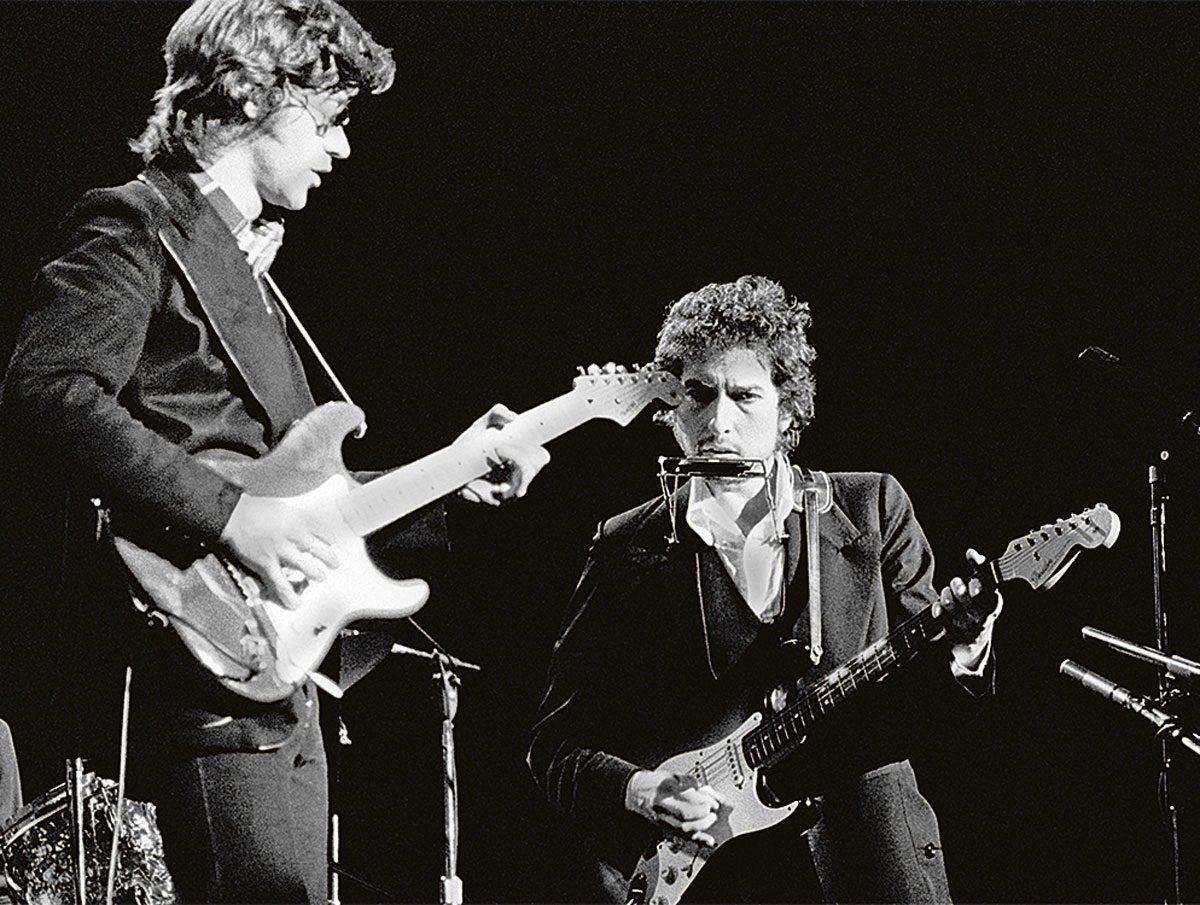

Hawkins, they soon realized, was holding them back. They craved independence, wanted to try new things. By 1964, they had split from Hawkins and abandoned the matching suits he made them wear. Soon after, they met a titanic musical force: Bob Dylan. Dylan had notoriously gone electric in 1965 and was looking for a band that could back him. It was the big time, but it was also an unexpected, dispiriting gauntlet. Betrayed folk audiences dismissed Dylan as a fame-hungry sellout. They booed his shows. Many blamed the Hawks, claiming they were ruining Dylan’s music.

By that point, Robertson was 22 and living in New York. Dylan had opened up his world. Robertson got a suite at the Chelsea Hotel. He was meeting everybody: Allen Ginsberg, Salvador Dalí, Carly Simon. On a movie set, he palled around with Marlon Brando, who kindly opened a Coke bottle for him with his teeth. At Dylan’s first wedding, he served as best man. A world tour took him off the continent for the first time, and he travelled to Hawaii, Europe, Australia.

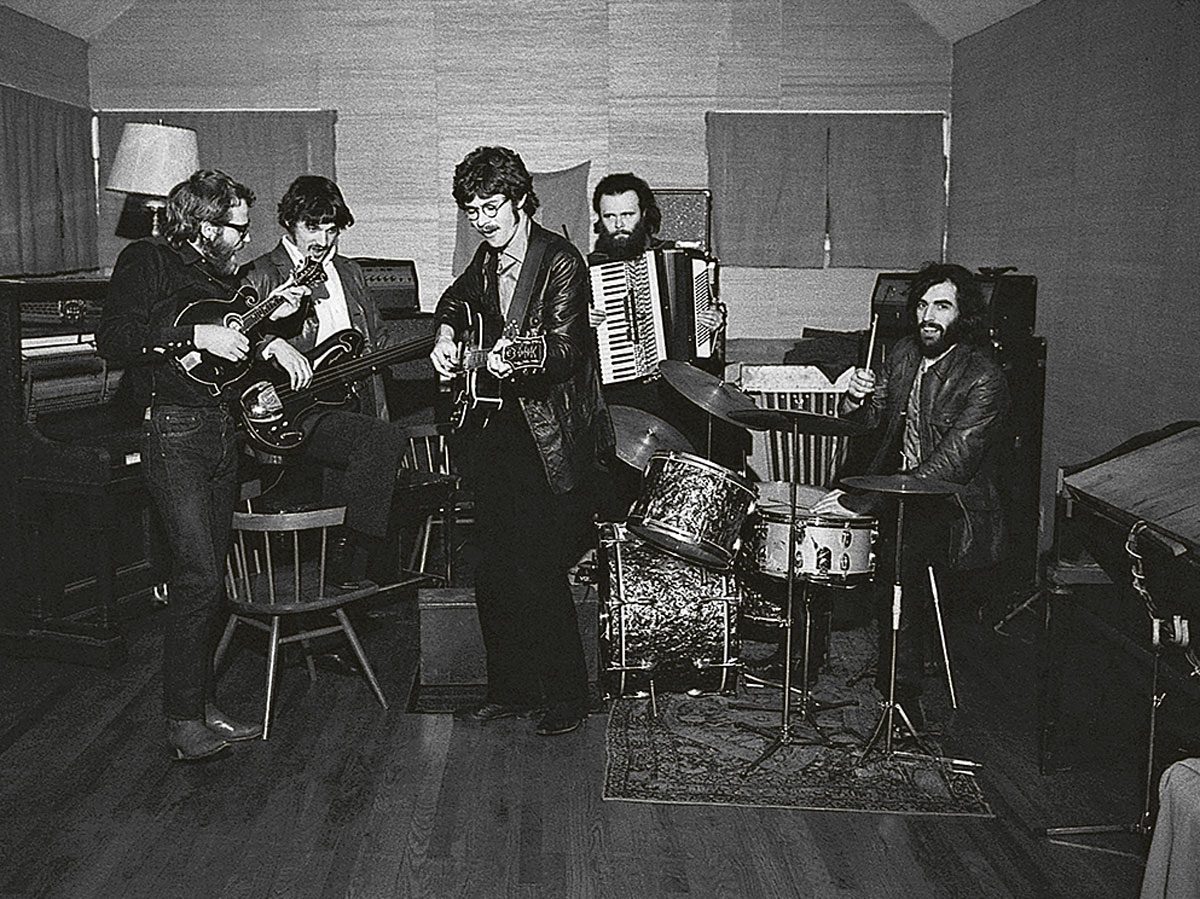

Dylan, however, was exhausted. A motorcycle accident in 1966 gave him the opportunity to, as he said, “get out of the rat race.” He retreated with his young family to Woodstock, in upstate New York. The Hawks followed, with Danko, Hudson and Manuel settling in a ranch house they dubbed Big Pink. Robertson and his future wife moved into their own place up the road, and Helm, who had temporarily left the Hawks, rejoined the gang. They transformed the Big Pink basement into a recording studio.

The basement became one of the most legendary laboratories in the history of rock. Here, the group created the quasi-field recordings and oddball ditties that became known as The Basement Tapes. Here, they composed their first record, 1968’s Music From Big Pink, including one of the most indelible songs in the American pop canon, “The Weight.” They then defiantly renamed themselves the Band, mainly because that’s what everyone in Woodstock called them.

If Robertson’s discovery of rock and roll had been a big bang, now, at long last, he had formed his own galaxy.

A year later, the Band cut their self-titled sophomore record, and it too contained instant classics, including “Up on Cripple Creek” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” The songs sounded like hymns written in the backroom of a 19th-century saloon, boogie-woogie ballads. They were woven from each of the group’s different singers, and no voice seemed more central than another. This was part of the Band’s secret, Helm said.

It would also be its undoing. Despite their ostensibly democratic configuration, the story of the Band soon became, as it did for so many musical acts, the story of who was the true voice of the group. Robertson and Helm vied to be the soul of the Band—or at least to be recognized as such. As the Band became more and more successful, the question of who was responsible for that success became an issue.

Robertson had written fewer than half the songs on Big Pink—Manuel was the other principal songwriter—but by the Band’s third album, Stage Fright, he was writing all of them. Initially, the Band had shared the publishing royalties equally, but by their sixth studio album, 1975’s Northern Lights–Southern Cross, Robertson had bought out Manuel, Danko and Hudson’s ends. He had written these songs, so why shouldn’t he get paid for them?

At least this is how Robertson tells it. In 1993, Helm published his own memoir, This Wheel’s on Fire, a rollicking, occasionally vitriolic tell-all that praises Robertson in one paragraph and excoriates him in the next. “The old spirit of one for all and all for one was out the window,” Helm wrote. “Resentment just continued to build.”

That resentment spilled over when Robertson proposed, in 1976, after seven studio albums, that the Band stop touring, regroup and figure out what to do next. He was tired of the road, which he’d never liked much to begin with. Plus, he was plotting his next move, which he hoped would be the movies: producing them, writing music for them, starring in them.

He befriended Martin Scorsese, a man who loved music as much as Robertson loved movies. They agreed that Scorsese would film the Band’s last concert, to be held at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, where they’d played their first show. “The Last Waltz,” as Robertson referred to the show, was electric, transcendent and joyous, and the ensuing movie is among the best concert films ever released. Afterward, Robertson refused to tour with the Band again and would never again make a record with them.

Robertson knows he’s been vilified. But he’s a guy more inclined to self-mythologizing than self-reflection. I asked him how it felt to be known as the guy who had put the Band together but who had also torn it apart. “I was the one who wanted the Band to continue,” he said. “I was the one who was the driving force in this group, and I drove it and I drove it until there was nothing to drive anymore.”

He didn’t care if I believed him, or what other people said. They weren’t there. And they aren’t here now. Except for the reclusive Hudson, Robertson is the only original member still alive. He was the one who’d survived, he was the one who got the last word, and here he was getting it again with me. He insists that he made peace with Helm before he died in 2012. “I thought to myself, what all he and I did together and all the things we came through and the music we made and this life experience, nothing can compete with that.”

It must be strange to be an elder, though, at this point in rock’s history, when so many of your musical brothers are no longer with you and others are blinking in the twilight. It must be strange when, like Robertson, you talk and talk about the past, and the stories from the past keep informing the story of the present. Robertson didn’t see it that way. “My natural mode is moving on, moving on, moving on,” he said. “What I’m doing with my life has to do with today and tomorrow. So these things, it feels good to go there because I don’t go there very often.” That wasn’t quite true. It was another story. But I sat and listened.

Next, here are the best concerts you can watch online right now.

© 2019, Jason McBride. From “Robbie Robertson’s Last Waltz,” Toronto Life (November, 2019), torontolife.com

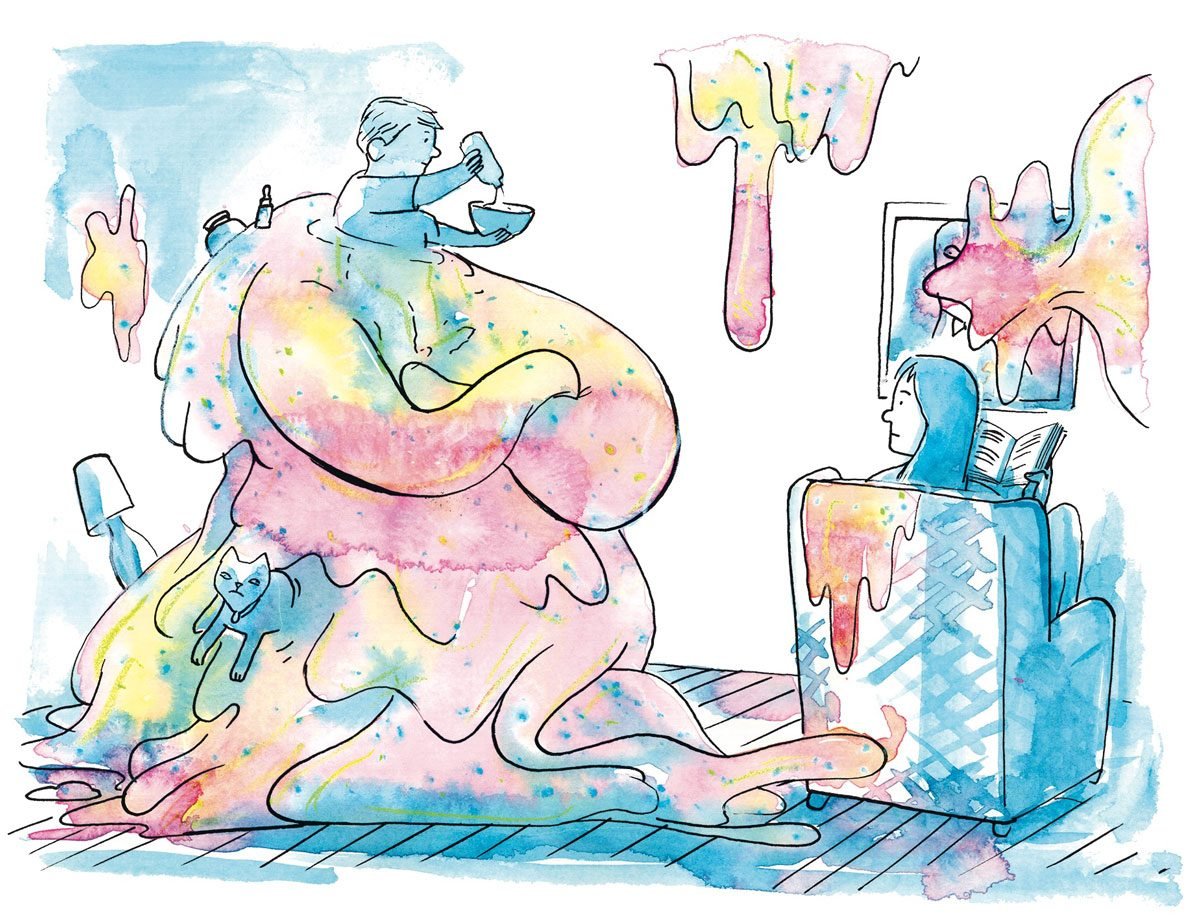

He Slimed Me

“I have an idea!” my son, Leo, said to me about a year ago, with a wild look in his eyes. “Let’s make rainbow slime!” It was not yet 8 a.m., and I was hard-pressed to think of anything I wanted to do less.

“Maybe later,” I offered my then-four-year-old, avoiding the more flammable answer that sprang to mind (i.e., “No”).

“But I neeeeeed to make something!” he pleaded, as if he were Monet, had just beheld a water lily for the first time, and here I was denying him oils and a canvas.

At the time, Leo was six months into his obsession with slime: we’d made fluffy slime, galaxy slime, clear-glue slime and retro Ghostbusters slime-kit slime. For the (blissfully) uninitiated, slime is a squishy, goo-like substance made from the viscous marriage of polyvinyl acetate glue, food colouring and some kind of “activator”—saline solution, laundry detergent, liquid starch— whose chemical makeup transforms all the other ingredients into a slippery, malleable glob. If those ingredients are non-negotiable, others (glitter, googly eyes, gummy bears) can be tossed in for a certain textural or aesthetic je ne sais quoi.

Slime was first devised by Mattel in 1976 and sold in toy stores, but the real slimers make it at home. Slime-making, I’ve read, can prove as relaxing for young children—a break from the pressures of, say, kindergarten—as it is for their parents. The substance’s popping, squishing and clicking noises, a sound the slime community (yes, there is one) has dubbed the “thwock,” are allegedly soothing to the nervous system.

Now, in 2020, slime has expanded into an economy, an art form and a culture, with its influencers, trailblazers—and tragedies. (An 11-year-old girl from Massachusetts sustained second- and third-degree burns on her hands in a DIY slime injury involving a dangerously toxic activator called sodium tetraborate.)

In Canada, Alyssa Jagan, an 18-year-old slimer from Toronto, just published her second slime book and claims 745,000 followers on Instagram, where she posts “new satisfying slime videos” every day.

All of this to say that if slime clung itself to my son’s imagination, he was on trend. But if it’s relaxing for many, it’s deeply anxiety inducing for me—I have found it encrusted on our couch and adhered into the fibres of our clothes (and our lives). At the height of what I can only call Leo’s addiction, I noticed my husband had glitter (a souvenir from the weekend’s galaxy-slime enterprise) in his nostril. When I pointed this out, he replied that I had a fleck of it on my left eyebrow.

“It’s so beautiful!” my mom said in an enabling way during one visit, as she spread out a glob of kaleidoscopic slime. “It looks like Notre Dame’s stained-glass rose windows!” I’m all for appreciating beauty wherever it may hide, but—and forgive the slime pun here—that seemed a bit of a stretch.

Parenthood is nothing if not a continuum of phases, and this one was a singular hell. Partly because I didn’t want to deny my kid something that provides him such deep satisfaction, I leaned into it, waiting for the day that a mention of Elmer’s glue wouldn’t kindle in him such a gleam of excitement. It’s messy, but it’s creative, I’d try to convince myself as I climbed a ladder to scrape a remnant of sand slime stuck to the kitchen ceiling.

The summer offered relief: we spent more time in the sunshine and less of the day mixing blue food colouring with glitter glue and liquid corn starch. But just when I thought (hoped, prayed, etc.) that Leo’s interest might be waning, COVID-19 arrived, demanding that we all stay home. While necessity is the mother of invention, in my case, it was also the less proud mother of derangement.

We can never predict how we’ll respond to a plague; it caused me, in a moment of diabolical instability, to say to my bored son, “I know, do you want to make slime?” He looked at me searchingly, as if even he couldn’t believe the extravagance of my misstep. “Okay!” he chirped, clasping his little hands in anticipatory madness.

There we were, again, in production. Leo gleefully began to toss cloudlets of fluffy slime (made with shaving cream) onto the walls, and he wondered, “Do you think it sticks, Mummy?” (PSA: it does.) As the concoction cleaved to my walls, in my mind was a combination of regret, despair and this question: how can I, in this moment, self-distance from myself?

People reveal themselves in a crisis, goes the truism, and I have revealed myself to be an idiot, with a talent for self-sabotage. However, I’ve also revealed myself to be a person who can expertly claim a position on whether or not to use Tide as an activator. (I prefer Persil.) And so this season of pestilence has bloomed into a season of slime—with moments of despair and longing, along with glittery flecks of hope, all mixed together, slime-like, as it were.

Next, read up on the best Canadian jokes from coast to coast to coast!

Science Explains Why Ghosts Are Haunting You

On television and in the movies, we bust ghosts, ghosts bust bad guys, and ghosts become our buddies. But when it comes to real life, plenty of people speculate they are much more than Hollywood smoke and mirrors; according to a HuffPost poll, 45 per cent of Americans believe in ghosts. (We can’t blame them—these nine royal ghosts haunt Britain to this day.)

The number may seem beyond belief, but another ghoulish number digs beyond just belief; 28 per cent of Americans claim that they’ve had a ghostly encounter of their own. And thanks to a new video from Vox, there may finally be an explanation for the paranormal activities.

When a dog whistle is blown, dogs react, but humans don’t. This is because the frequency of the pitch is of a frequency outside of a human’s hearing ability. Neil DeGrasse Tyson explains in the video how even though we can’t necessarily hear these frequencies, they can still produce vibrations which we sense, which can, in turn, trigger us into visualizing things which are not actually present.

Science just loves spoiling ghost stories.

Next, here are five famous ghost stories that have been debunked.

We’ve all been there. You’re in the middle of baking something, you reach for the next ingredient and—the horror!—it’s not there. Whether you’re missing eggs, milk, baking soda or something else, you’re left with two not-so-awesome options: sprint to the store or find a replacement ingredient. (Don’t miss these 20 secret cake baking tips we learned from grandma.)

If you’ve ever been in this position with powdered sugar, then today’s your lucky day. TikTok has shown us how to make powdered sugar in seconds, and it’s definitely easier than you were thinking. Here’s how it’s done!

Can You Make Powdered Sugar?

Yes—and to make powdered sugar at home, all you need is regular granulated sugar. It’s as simple as dumping the amount of powdered sugar you need in a blender, turning the blender on and keeping it running until the granules are a fine powder. Boom! Instant powdered sugar. (Did you know you can also use a blender to make the healthy, homemade creamer recipe this nutritionist loves?)

To see the magic in action, check out this TikTok. It’s worth noting, though, that to prevent a super-sweet cleanup, you shouldn’t fill your blender with sugar. As the TikTok’er in the video shows, it’s best to keep it half-full, at most.

@boggle.boggle##stitch with @_nikasonye ##fyp ##foryoupage♬ original sound – boggle

Next, satisfy your sweet tooth with these instant Rice Krispies treats that only require two ingredients!

How to make a healthy coffee creamer

Finding a healthy creamer can be tricky, especially if you want something flavourful and made with all-natural ingredients and healthful fat. When I face the wall of creamers at my local market, the first thing I do when I pick up a bottle is turn it over and read the ingredient list.

I love to see the variety of new plant-based options, but there are a handful of deal-breaker ingredients I don’t want in any creamer I use or recommend.

For example, after water, the next ingredient in many creamers is sugar. One level tablespoon of creamer can provide 4 grams of added sugar, just about a teaspoon worth. If you use a quarter cup of creamer in your coffee (or coffees if you drink more than one cup), that adds up to 4 teaspoons worth of added sugar. (Check out the 25 ways the sugar in your diet is harming your health.)

That’s getting close to the American Heart Association‘s recommended daily cap of no more than 6 teaspoons of added sugar per day for women and nine for men.

Other red flags include artificial colours, flavours, sweeteners and preservatives, additives commonly found in highly processed foods. A 2019 study, published in Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, raises concerns about the potential link between processed foods and obesity.

Researchers theorize that processed foods, and the additives they include, may create an imbalance in the gut by affecting bacteria in ways that alter their metabolism, and subsequently increase chronic disease risk.

A study published in the July 2020 journal Nutrients, also agrees and concludes that a high consumption of ultra-processed foods is linked to health risks. Of 43 previously published studies scientists reviewed, 37 showed that exposure to ultra-processed foods was associated with at least one adverse health outcome. Among adults, these included obesity, cancer, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, irritable bowel syndrome and depression. (Don’t miss the nine worst foods for your heart.)

An instant alternative

For an instant alternative to creamer, start with a plain, unsweetened plant-based milk made from simple ingredients. One of my favourites is Elmhurst 1925 unsweetened almond milk. The only two ingredients are water and almonds.

I also like Trader Joe’s Non-Dairy Oat Beverage, made from just water and hydrolyzed oats. To sweeten, add one teaspoon of pure maple syrup per quarter cup of plant milk. This two-ingredient version won’t be as thick as a creamer, but it’s fast, flavourful, and much more healthful than a highly processed product.

Homemade creamer recipe

If you want something homemade, you can opt for my DIY creamer recipe. After all, the healthfulness of a food becomes even more important the more frequently you consume it.

If you start every day with coffee, and you typically add creamer, consider this recipe with just a few simple ingredients and steps. Here’s my DIY creamer recipe for a nutrient-rich whole food option that will keep in the refrigerator for 4-5 days. (Here are 10 more ways to make your coffee habit healthier.)

Cashew Chia Creamer

The three ingredients that form the base of this creamer are each nutrient powerhouses. In addition to heart-healthy fat, cashews provide 5 grams of plant protein per ounce (1/4 cup), and a range of nutrients, including B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, iron, manganese and antioxidants.

The chia seeds will thicken the creamer, but they also add healthy fats and anti-inflammatory antioxidants. Medjool dates add sweetness without counting as added sugar. (Don’t miss the six most impressive health benefits of chia seeds.)

That’s because they’re considered a fresh fruit, since no water is removed and the dates are unprocessed. Dates also provide a wide range of antioxidants, in addition to vitamins and minerals, like potassium, which helps regulate blood pressure, and supports nerve and muscle function and heart rhythm.

Ingredients:

- 1/2 cup whole raw cashews

- 1 teaspoon chia seeds

- 2 whole, pitted Medjool dates

- Pinch sea salt

- 3/4 cup brewed and chilled chai tea or plain, filtered water

Instructions:

Place the cashews, chia seeds, and dates in a medium bowl and add enough water to cover the mixture. Soak in the refrigerator for at least two hours or as long as overnight.

Drain off the water and transfer the mixture to a blender. Add the sea salt, and either the chai tea for flavour, or plain filtered water.

Blend on high until smooth. Strain the milk through a nut bag until all of the liquid has been extracted and the pulp is left behind.

Tip: Use decaffeinated chai if you’re a decaf drinker.

A nut-free version

If you have a nut allergy or sensitivity, you can make a nut-free version of this same recipe.

Replace the cashews with 1/2 cup of organic old-fashioned rolled oats. Do not drain after soaking.

Add just 1/4 cup of water or chai tea, blend, and strain. Each version makes about one cup of thick, rich creamer.

Next, pair your coffee with the healthy banana muffin this nutritionist swears by.

If you’ve ever been on the receiving end of a cat’s teeth sinking into your skin, it makes sense you’d want to ask the question, “Why does my cat bite me?!” Sometimes it’s an aggressive bite that sends you yelping, other times it feels like more of a mild warning bite, and there are even instances where it seems like a gentle love nibble. Below, we’re discussing all three scenarios and also offering guidance on how to navigate this tricky topic.

What are the common reasons why cats bite?

The short answer to “why does my cat bite me?” is that they’re trying to tell you something. The long answer is a bit more nuanced, but we can break it down into three categories: they’re feeling annoyed or threatened, they’re trying to get your attention, or they’re playing.

“The most common reason why a cat bites you is that they aren’t enjoying the current interaction. Biting is their way to say ‘back off’ when they feel threatened [or annoyed],” says Rachel Barrack, DVM, a veterinarian at Animal Acupuncture in New York City. “Cats also may bite when playing as they are natural predators.”

Deborah S. Greco, DVM, a veterinarian and the senior research scientist for Nestle Purina Petcare, adds that a cat might also bite if they want or need something from you. In that sense, they may use biting as a means of trying to communicate that need. For example, maybe their litter box needs cleaning, they’re craving some playtime, or they are hungry.

“It’s important to carve time out of your day to play with your cat, to check that their litter box is clean, and to make sure that they have plenty of food and water to help minimize the biting,” says Dr. Greco. (Here’s a point to ponder while your kitty is napping—what do cats dream about?)

Do certain behaviours trigger my cat biting me?

As mentioned above, a common reason why cats bite is that they are afraid, angry, or annoyed. “This makes it especially important never to tease your cat, which can be frustrating and threatening,” says Dr. Greco. “Also, if your cat has a medical condition, they may bite because of the pain they’re feeling. Whatever the reason, a cat often gives warning signs before they bite. If she is hissing, flattening her ears, or emitting a low growl, it’s time to back away.”

How common is it for cats to bite?

Generally speaking, it’s pretty common for cats to bite, and there many reasons why they may suddenly start biting, seemingly unprovoked. It’s important to understand that cat biting isn’t always because of aggressive behaviour but can happen for reasons we outlined above. (Here are 14 common “facts” about cats that are actually false.)

Do cats ever “love bite”?

A “love bite” might look like a gentle nibble or your cat gently holding their teeth on your skin without pressing too hard. This is a much more common behaviour between cats, but some cats might also do it to their owners.

“A playful nibble or love bite is very different from a truly aggressive bite that typically is in conjunction with hissing and meant to cause harm,” says Dr. Barrack. Think of it as a really weird cat way to say, “I like you!” (This is the answer to the “why do cats like boxes” question.)

Is a cat bite ever dangerous?

Given how small domestic cats are, you’d think that a bite wouldn’t be a big deal. That’s not the case, however. Dr. Greco says, “Cat bites are extremely dangerous due to the bacteria present in a cat’s mouth! If your cat bites you and it breaks the skin, you must clean the bite immediately with warm soapy water.”

She also recommends seeing a doctor for antibiotics, especially if the bite caused bleeding or if you notice that the wound site stays red and inflamed. On that note, in the event another pet (including another cat) is bitten, a visit to the vet is also in order. Bottom line: never ignore a cat bite. (Can cats get coronavirus?)

Are there ways to discourage a cat from biting me?

The simplest way to reduce your cat’s biting behaviour is to avoid doing the things that make them bite in the first place. For example, if you notice your cat bites you when you pick them up a certain way, that’s their way of saying, “I don’t like this!” Ceasing that particular action will prevent biting in that scenario.

If your cat bites a lot when you play together, Dr. Barrack recommends providing toys that your cat can bite and play with instead of you. Continue to play with them but use a toy as the “middleman” so to speak. “You can also reward them when playing with their paws and not play biting. Always reinforce positive behaviours,” she says. That might look like head scratches, positive talking, or even a treat. (These are the seven reasons why cats clean themselves so much.)

When should you talk to your vet about cat biting?

“Should your pet suddenly show changes in behaviour—such as aggression which includes biting—veterinary attention is required to determine if there is an underlying medical condition causing this behaviour,” says Dr. Barrack. A veterinarian can also help you curb the biting issue if it is simply behaviour-based.

Next, here are the 12 cat breeds that get along with dogs.

One of the most common ways to call out a false statement is to say it’s a “bold-faced lie,” or perhaps a “bald-faced lie.” In fact, nowadays, you barely ever hear the phrases “bold-faced” or “bald-faced” in any other context besides responding to a lie. But if you’ve heard both of these expressions, you may have wondered…which is it? Is it a “bald-faced lie,” as in a totally exposed, uncovered falsehood? Or is it a “bold-faced lie,” as in a big, blatant lie in bold print? Only one of them can be right…right?

You probably think that only one of these expressions is the “correct” one, and that the other is just one of these words and phrases you’re saying wrong. But in this case, in a surprising linguistic twist, both “bold-faced lie” and “bald-faced lie” are generally considered valid expressions!

What does “bald-faced lie” mean?

Interestingly, this phrase was born out of a slightly different one: “bare-faced lie.” And, yes, both expressions refer, figuratively, to hairlessness. First recorded around the late 1500s, “bare-faced” (or “barefaced“) both referred literally to a hairless man and figuratively to a brash, forward quality or action. (What an interesting societal comment on clean-shaven men at the time!) However, “bare-faced” wouldn’t be recorded as specifically describing a lie until the 1800s.

As “bald” became the prevailing word for hairlessness, the expression evolved accordingly. “Bald-faced lie” became the prevailing way to describe a brash un-truth in the mid-20th century, according to Merriam-Webster. Though you’ll still hear “bare-faced lie” today, it’s not nearly as popular as “bald-faced lie” or “bold-faced lie.” (Check out these nine famous quotes everyone gets wrong.)

What does “bold-faced lie” mean?

“Bold-faced” was also around for quite a while before it began primarily describing lies. It was likewise first recorded in the late 16th century, and it meant, well, bold (usually with a negative connotation). But when it came to describing lies, it didn’t rise to popularity until the late 20th century, after “bald-faced lie” had started to gain prevalence. And Merriam-Webster believes that the use of “bold-faced lie” surged because of the sudden popularity of “bold-faced” as a type of print, like for a newspaper headline—and people conflated that phrase with the use of “bald-faced lie.” For that reason, Merriam-Webster considers “bald-faced lie” the slightly more “legitimate” expression: It’s “decidedly the preferred term in published, edited text.”

But hey, “bold-faced” was already an expression before this typographical mix-up—and it meant exactly what people mean when they say “a bold-faced lie.” So don’t sweat it—”bold-faced lie” and “bald-faced lie” are both valid. No matter which of these you use, people will know what you mean.

Next, find out the 12 funniest new words added to the dictionary in 2020.

The benefits of self-care

Last March and April, I woke up every morning trying to shake off a bad dream—something grey and heavy, something about a virus. Every morning, I’d realize it was, somehow, real. But even as I have integrated the “new normal” of lockdown and social distancing into my consciousness, the stress, fear and grief of the situation can still overwhelm me.

A difference-maker throughout this time, however, has been my self-care routine, a set of practices and habits that I’ve followed since my 20s, before I even knew there was a “self-care” movement.

While the term “self-care” might bring to mind Instagram hashtags and spa days, it has two legitimate origins. Before it went mainstream, “self-care” was used to describe guidance on what sick people and their caretakers should do to support the work of getting healthy. And, women and Black people used the term to describe the kind of care not provided by a white, patriarchal medical establishment.

It’s fortunate that self-care is now more widespread, as people of any age can make use of the movement’s lessons during this pandemic. Here are some starting points.

Settle your mind

Even before COVID-19 arrived in Canada, we had been experiencing a mental health crisis. According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada, mental health challenges cause around 500,000 people to miss work each week. And in a recent Morneau Shepell survey, 36 per cent of Ontarians reported their mental health has suffered since the pandemic began.

One pillar of self-care that can help ease the mental burden—and which also happens to be simple, efficient and free—is meditation. The positive impact of meditation on anxiety, depression, focus and even physical pain has been so well-established that it is now used in schools, on sports teams and in corporate offices.

Still, it can be difficult to create and maintain a regular meditation practice. Light Watkins, a nomadic meditation teacher who’s settled in Atlanta for the pandemic, says that a lot of people don’t meditate because, at first, “It doesn’t feel all that relaxing.” That’s partly because meditators are encouraged to sit upright on a mat or cushion on the floor; I like to meditate in bed. Watkins says, “You want to sit in a way that feels absolutely comfortable, like you’re watching television,” and he notes that a sofa or reading chair works well enough.

And while various meditation practices involve focusing on something specific—the breath or a visualization—Watkins suggests to instead try mental “roaming.” With your eyes closed, let yourself think about the past, the future, conversations, songs—whatever comes up. “You don’t want to wrestle with your thoughts,” he says. “The practice is to adopt an attitude of complete nonchalance.” Counterintuitively, letting your mind wander freely allows it to settle.

Meditation won’t reverse decades of accumulated stress, Watkins warns. But with time, you’re more likely to become resilient when you need to be.

Roll away stress

When you’re under stress, overwhelmed or, yes, living through a pandemic, regular exercise can be one of the first healthy habits to go. Yet moving your body is a core principle of self-care and one of the best defences against stress. For anyone who feels that squeezing in a workout is too much right now, Melanie Caines, a yoga teacher in St. John’s, Nfld., suggests movement needn’t mean doing a serious workout every day. “A little goes a long way,” she says. In fact, some targeted, gentle exercises can do a lot to relax your entire body.

Since the average person is inclined to hunch their shoulders when they work, read or even walk, Caines recommends taking a break for shoulder rolls. To do this, start by inhaling, lifting the shoulders toward the ears, exhaling and “smoothly and gently” rolling the shoulders back and down. Caines advises to do this without any “jerky movements,” but instead with “fluidity and ease”—and only if it feels good and there’s no pain.

Another activity that people often don’t make time for is intentional breathing. “We breathe just enough to stay alive and stay conscious,” says Caines, “and we don’t use this incredibly powerful tool that we have in our back pockets.” For a reset at any time during the day, she suggests taking a breath in through the nose, opening the mouth and sighing. “Physically, you’ll start to release tension and soften.”

Get your vitamins

It’s easy to resort to unhealthy foods as a comfort or distraction during a difficult time, which only makes it harder for your body to deal with stress. An important self-care tactic is to be mindful about what you’re eating and consider adding some nutritional support.

In general, this means a balanced diet that is right for your needs. But one commonly overlooked piece, according to Toronto naturopathic doctor Nikita Sander, is vitamin D. She notes that the nutrient is protective in many ways and is key for mental health: “Vitamin D helps regulate adrenalin and dopamine production, and prevents the depletion of serotonin in the brain, making it important for protecting against mood disorders like depression.”

Vitamin D also supports the immune system. Sander notes that deficient levels of it have been associated with certain cancers, autoimmune disease, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. “This suggests that vitamin D has a much greater role in our overall health than we yet understand.”

Sander also encourages people to consider taking an adaptogen, which is an herbal supplement that helps the body cope with stress. She likes ashwagandha, which can help balance cortisol, a stress hormone. “When our cortisol is high, that can often wreak havoc on other aspects of our health, including our energy levels, our ability to sleep and our ability to stay calm,” she says. As always, however, discuss any new supplements with your doctor first to avoid any contraindications.

Self-care can extend in many directions. Over the last few months, I upped my own routine by starting a running program with a friend, taking barefoot “grounding” walks in the backyard and keeping a daily journal. Self-care, as the name suggests, is whatever you make it.

Next, discover how to make new friends—even if you’re all grown up.

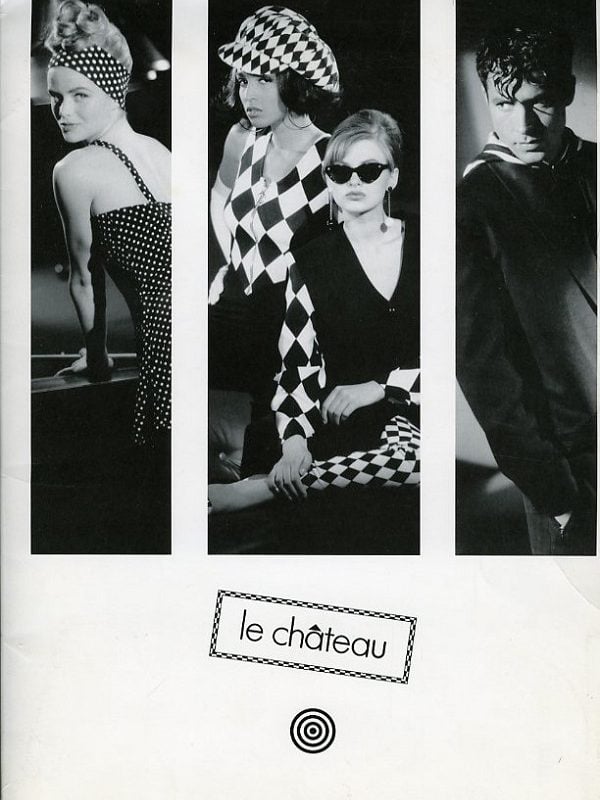

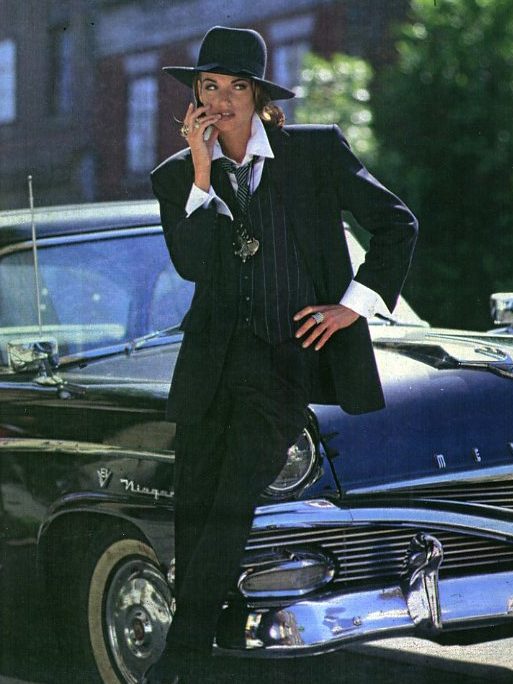

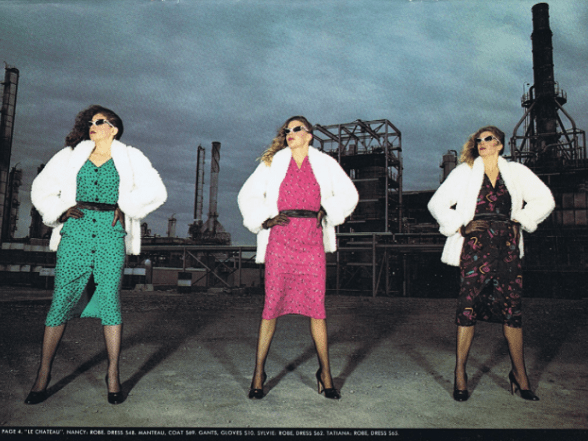

Growing up, Le Château was always the “prom store.” When news broke that the Montreal-based retailer had filed for court protection from creditors and would be liquidating all 123 of its stores, countless Canadians of a certain age—namely, millennials 30 and above—shared memories of two-tone organza spaghetti strap dresses and midriff-baring one-shoulder tops. In its late ‘90s–early 2000s heyday, Le Château was a veritable bastion of slinky lurex dresses and “going out tops”—flimsy pieces of fabric held together by pieces of string. The brand’s clothes were ostensibly aimed at people above legal drinking age, but also somehow ended up worn by preteens with a 9 p.m. bedtime. I vividly remember experiencing my first whiff of independence after being dropped off with a friend to walk unsupervised around the Quinte Mall in Belleville, Ont., where we would make a beeline towards Le Château to gently caress racks of flared polyester pants that laced up on the side and dream of the people we would someday become.

Now Le Château now joins Cotton Ginny and Zellers in the retail graveyard of once-beloved Canadian stores that, sadly, just weren’t able to make it work. Founded in 1959 by Montreal fashion retailer Herschel Segal, Le Château initially sold discounted overstock clothing before it became the centre of Canada’s 1960’s youthquake. Segal introduced European styles to a fashion-forward crowd and has claimed to be the first person to introduce bell bottom pants in Canada. John Lennon and Yoko Ono donned Le Château black velour tracksuits for their 1969 Montreal bed-in for peace—the ultimate coup in cool.

By the 1980s, the brand had rebranded as a mall staple and became what was essentially a progenitor of H&M and Zara: an emporium of hyper-trendy, disposable clothing available at a mid-range price. But what set Le Château apart from its global competitors was its longstanding commitment to Canadian manufacturing. Le Château was one of the few remaining fashion brands that continued to produce a portion of their offerings in Canada—a stalwart holdout of Montreal’s once-booming garment district.

But in recent years, Le Château’s often-flimsy clubwear failed to attract the cool teens it had once effortlessly catered to. While working as a fashion editor, I recall being invited to the Eaton Centre for a sneak-peek at the season’s new offerings. The fluorescent-lit store was packed tight with tailored blazers and boot cut pants made out of borderline flammable material, slouchy camel coats and bridesmaids dresses. Yet despite the literal cornucopia of stuff, I couldn’t find a single item of clothing I wanted to wear. I left the store empty-handed.

In the end, Le Château was a victim of the pandemic (it’s owners cited Canadians’ changing shopping habits, especially the drop in demand for prom wear) as well as its own pragmatism. By manufacturing milquetoast work clothes for a nebulous demographic of “young professionals,” Le Château lost the elusive aspirational quality that remains key to maintaining a successful fashion brand. Had they shifted gears and attempted to target a specific customer—early 2000s nostalgia-core, loose flowy linens, or even athleisure bae—they might have stood a chance at recapturing the zeitgeist. In their efforts to cater to everyone at once, they ended up appealing to no one at all.

I wish Le Château’s dedication to Canadian manufacturing had been enough to save it. The company has skirted death before. Segal first went bankrupt in the early 1960s, and was close to shuttering the company in the late ‘90s, early 2000s and early 2010s. Still, something about Le Château felt permanent. I took it for granted that Le Château would emerge out of this difficult period unscathed, just as they had the previous 60 years.

Two months before the COVID-19 pandemic began shutting down businesses and schools across the country and infecting thousands of Canadians, I was already in a near-constant state of worry. Unlike others, I wasn’t thinking about whether I would lose my job or contract the novel coronavirus. I feared Asians in Canada would be blamed for the impending catastrophe.

With COVID-19 cases in Canada now surpassing 200,000 and a second wave already underway in some provinces, that fear has not disappeared.

Every time I walk to the local supermarket, I now find myself questioning every glance towards me. “Can they tell that I’m Asian?” I ask myself. “If they can, how does that make them feel?” I haven’t been on public transit since March, fearful of getting into an altercation. When my brother or friends offer to hang out, I reply with one condition: “Only if we’re travelling by car.”

As a Canadian of Filipino descent living in Toronto, I’ve never fully believed that Canada is a land of cultural acceptance. While the neighbourhood I’ve lived in for 12 years is a mix of white, East Asian and South Asian residents, I’m no stranger to being the only person of colour in a room full of white people.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve faced seemingly innocuous questions about my country of origin, whether English is my first language, and my cultural values. When people ask me these kinds of questions, what they’re really trying to do is remind me of my “otherness.”

Shining a spotlight on anti-Asian racism

Anti-Asian racism in Canada is nothing new: Chinese immigrants arriving in British Columbia in the 1850s were met with hostility from white residents. The province’s labour leaders eventually lobbied for restrictions on the employment, housing and education of Asian Canadians. Then, during the Second World War, the federal government removed over 22,000 Japanese Canadians—some of whom were Canadian by birth—from their homes and sent them to live in internment camps in British Columbia.

The cruel treatment of Chinese people in Canada during the SARS outbreak in 2003—Chinese students being harassed at school, people of Chinese background being taunted on public transit and widespread mistrust of East Asian communities—is yet another reminder of how far we haven’t come. I was only eight during the SARS outbreak. At the height of the epidemic, my dad underwent an appendectomy at Scarborough General and a SARS-related death at the hospital forced him into quarantine. But while I was aware of the disease’s existence, my parents kept me in the dark about the discrimination Asian-Canadians faced during that period.

As an adult, I’m naturally more aware of the persistent negative perception of East Asians. Days after France confirmed its first coronavirus cases in January, French newspaper Le Courier Picard ran the headline “Le péril jaune?” (Yellow peril?) above an image of a Chinese woman wearing a face mask. Later in March, U.S. president Donald Trump, who continues to downplay the seriousness of the coronavirus, began referring to it as the “Chinese virus.” Then in June, Trump called the virus “Kung flu.”

Times of uncertainty have a way of unleashing racism. When it comes to epidemics, the general public often blames marginalized groups. West Africans were blamed for Ebola in 2014, Mexican-Americans for swine flu in 2009, the Chinese for SARS in 2003 and, even further back in time, Italian immigrants for the 1916 polio epidemic in New York City and Jewish communities for the bubonic plague in the 1300s. Misinformation and fear don’t breed racism, but simply bring to light what has long been embedded in Western culture.

When my worst fears came true

Back in February, I voiced my concerns to only a few colleagues. My parents, meanwhile, had resigned themselves for the inevitable backlash and didn’t linger too long on the subject. I saved my deepest anxieties for my best friend. That unease only increased as news of racist incidents closer to home took over the headlines.

In March, a white man shoved a 92-year-old Asian man outside a convenience store in East Vancouver. According to staff members, the suspect had been shouting racist remarks about COVID-19 at the senior moments before the attack. The suspect was later identified and charged with assault in July.

Then in May, a 40-year-old white man subjected a 15-year-old Asian teen to a racial tirade in a public park in Saskatoon. After the teenager took a picture of the suspect, the man “chased him, [pushed] him off his bike, punched him in his helmet and tackled him.” Police later arrested the man, who appeared in provincial court in August.

And in July in Toronto, a Filipino woman, Justine Abigail Yu, was reading a book on the grounds of a public school when a white woman claiming to be a teacher confronted her. “The woman says there’s signs here that say no trespassing,” Yu recounted in a video posted on her Instagram profile. “[Then she said], ‘Maybe you can’t speak or read English, maybe you should go back to China or go back to wherever it is you’re from.’” The Ontario College of Teachers declined to comment on the investigation, while the Toronto District School Board is currently determining if the woman in question is indeed an employee.

In a recent study from the Angus Reid Institute and the University of Alberta that surveyed more than 500 Canadians of Chinese ethnicity, 50 per cent of respondents reported experiencing insults directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Forty-three per cent of those surveyed also said they’ve been threatened or intimidated since the start of the pandemic, while 61 per cent said they’ve adjusted their daily routines in order to avoid potentially racist encounters.

“When the president of the United States calls COVID-19 the ‘Chinese Virus,’ racism becomes legitimate and may even become normalized,” Pamela Sugiman, a sociology professor at Ryerson University, said in an interview with Ryerson Today. “It’s difficult for people to push back because we’re in the midst of a pandemic and everyone is feeling scared and vulnerable.”

How to respond to anti-Asian racism

At the start of the pandemic, Theresa Tam, Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, wrote on Twitter: “We need to learn from our experience with SARS, where Southeast Asians faced significant racism and discrimination. Racism, discrimination and stigmatizing language are unacceptable and very hurtful. These actions create a divide of ‘Us vs. Them.’”

Underlying each act of anti-Asian racism is the tired notion that Asians are a monolith. We have been reduced to a single identity and experience. If one of us is perceived to have made a mistake, then many may believe we all deserved to be scapegoated.

But we are not a monolith. We come from dozens of countries in Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and the Far East. As of 2017, there are 1.8-million Chinese people in Canada, with Filipinos accounting for a further 837,000 residents. Some Asians have come to Canada resisting oppression in their native lands. Others have lived in their adopted homes for decades. Some of us have little to no connection to our descendants. We’ve done our best to integrate while also fiercely holding onto our traditional values.

Apathy, however, is the biggest obstacle we face in fighting racism against Asians.

If you are the victim of anti-Asian racism or witness an incident, it’s important to speak up. This present moment in time requires that we support one another and protect victims of hatred. I recommend Fight COVID Racism, a website that features a detailed timeline of anti-Asian incidents in Canada, an incident map, and a form to report racist occurrences.

Just like the Black Lives Matter movement has inspired people of colour around the world to speak out on how they experience race and racism in their own countries, Canadians also need to better educate themselves on our country’s history of anti-Asian racism. Our new normal in Canada consists of face masks, physical distancing and remote work to flatten the COVID-19 curve. We must try to stop anti-Asian racism in its tracks, too.

This story was first published on October 1, 2020.

Next, learn about Caremongering Toronto, the group that inspired thousands of Canadians to help each other through COVID-19.

Foods Nutritionists Never Eat Late at Night" width="295" height="295" />

Foods Nutritionists Never Eat Late at Night" width="295" height="295" />

The 100 Funniest Quotes of All Time" width="295" height="295" />

The 100 Funniest Quotes of All Time" width="295" height="295" />