At one time or another, most of us have complained about feeling dissatisfied with a visit to the doctor’s office. When I hear people voicing their concerns to anyone who will listen—except their doctor—I’m convinced that part of the problem lies in our difficulty speaking honestly with authority figures.

The health care system has changed over the past few decades. Hospital stays are shorter, and walk-in clinics are more frequently used, in part due to the lower number of GPs accepting new patients. In today’s system, you play an important role in your own care. Here are tips on how to talk to your doctor in a manner that conveys your needs clearly and efficiently, so your time with the doctor is as helpful as possible.

Humanizing your doctor

We expect a lot of health practitioners: to spend a reasonable amount of time with us, to communicate effectively, to be in a good mood and to have answers to all our medical questions.

If you ask patients whether these expectations are met, some will say yes, but the majority feel let down. Why? It may be that our expectations are unrealistic, or it may be the result of a breakdown in communication.

Patients often think of their doctors as infallible, but open conversation can change that. If we see our physicians as ordinary people, our expectations will become more realistic.

For example, when a patient visited her doctor for a cold, the doctor was annoyed with her for taking up valuable time. The patient was surprised that he would speak to her so irritably. When he saw her reaction, the doctor apologized. He explained that he had a heavy patient load that week and was also worried about his young daughter, who was sick. The patient realized that perhaps her doctor had a point about a needless visit and that he, too, had personal stresses.

Communicating discomfort

Tell your doctor if you feel uncomfortable with any aspect of your care. You may be uneasy with groin, rectal or breast examinations, for example. A doctor will usually understand and try to decrease your nervousness. But you might want to think about whether the problem could be your own aversion to invasive procedures, which is not uncommon.

If this is the case, you could try thinking or chatting about other things during such exams. Joking can help both the patient and doctor relax. If, however, you still don’t feel at ease, it might be time to consider finding another doctor.

Feeling ignored or dissatisfied

Expressing how you feel to your doctor is important. However, not everyone is open to hearing your criticism, especially if that person is the target. Choosing the right time is important, as is figuring out how to make your point without causing offence. The old adage that you can catch more flies with honey than vinegar rings true, as long as sincerity is a critical ingredient.

Suppose you feel your doctor doesn’t grasp your symptoms accurately. You decide he or she is being obstinate and unwilling to hear what you have to say, and perhaps you’re right. However, you might be able to get your message across by saying, for instance, “Doctor, for some reason, I don’t seem to be describing my symptoms clearly. I wonder if there is some other way I could describe them to help you understand.” This would give your doctor an opportunity to recognize that he or she isn’t on the same page as you.

Exploring your family medical history

We often forget to inform the doctor about crucial family information that might affect diagnosis, prognosis, intervention and even medical treatment. There are many conditions with hereditary factors, such as heart disease, stroke, mental illness and certain types of cancer. If your doctor knows about these patterns, you can discuss which symptoms to watch for and which preventive steps to take.

Imagine a patient becomes concerned about her risk of a stroke, so she books an appointment with her doctor to discuss it.

“I had no idea about the history of strokes in my family until my grandfather’s last year,” she says. “My mother told me that her own grandfather had died of a stroke, too.”

“I see,” says the doctor, taking notes. “I’m glad you’re telling me now. Better late than never.”

“Then a friend told me that chronic stress can add to the risk,” says the patient. “I have a high-stress job, so I began to worry.”

“I think it’s premature to start worrying,” says the doctor. “A family history of stroke is no guarantee that you’ll have one, too, and there are lots of things you can do to reduce your risk.” She explains some of the lifestyle factors the patient could control, before finishing up by saying, “You were right to tell me about this possibility. It gives me a good frame of reference and means we can work together to keep you as healthy as possible.”

The patient leaves the doctor’s office feeling relieved—and with a lot of accurate information about strokes. (Find out the difference between a stroke and an aneurysm.)

Discussing symptoms

You should take note of any changes in your body—such as unusual lumps, rashes or persistent pain—and be sure to communicate them to your health practitioner. It allows for early detection of potentially serious conditions and will give your doctor the opportunity to hear about any worries you might have. (Here are 50+ health symptoms you should never ignore.)

Often, we don’t let the doctor know of the upsets and stresses in our personal lives, even though they might contribute to changes in our health. Emotional problems can, for example, aggravate depression, migraines, backaches, fatigue and stomach pain.

“Doctor,” says a patient, “my headaches have become a lot worse since my wife and I separated last month. They’re interfering with my work, and I’m finding it difficult to concentrate. I’ve tried taking over-the-counter painkillers, like you suggested last time, but they don’t seem very effective. I don’t know what to do.”

“Oh,” says the doctor, “I didn’t know last time about all these changes in your life. They could certainly be increasing your tension levels, which could be a reason for your headaches. How about if I check a few other things?”

As she measures his blood pressure, she asks the patient to tell her more. The patient describes how he feels about the breakup of his marriage and the stresses of his job. By the end of the visit, he feels more relaxed about his situation. (Discover the surprising things that could be affecting your blood pressure reading.)

Using metaphors

A smart analogy can be an effective way to communicate degrees of physical or emotional pain. Look at the following examples:

- “It feels like my shoulder has been pierced by an arrow.”

- “My stomach feels bruised.”

- “My muscles feel as if they are on fire.”

- “My heart feels overwhelmed with grief.”

- “I feel a crushing sense of responsibility, as though I’m carrying a heavy knapsack.”

There are many words or images you can choose; the point is to find a way to describe exactly how you feel.

For example, after a hockey accident, a patient felt as if his knee would explode. “I can see that you’re in a lot of pain,” said his doctor. “Where does it hurt most?”

“Here,” said the patient, pointing to the side of his knee.

The doctor gently touched the knee. “It’s quite swollen,” she said.

“It’s burning, throbbing,” said the patient. “Please give me something to ease the pain.”

“First, tell me how deep the pain is,” said the doctor. “Can you describe it?”

“It feels as if a knife is piercing a nerve.”

“I see,” said the doctor. “Has it been gradual?”

“Yes, it started slowly,” said the patient. “But then it suddenly got worse.”

In this way, the patient gave his doctor a picture of his pain that allowed for appropriate treatment and speedier recovery.

Paraphrasing

Putting what you hear into your own words is an element of good listening. It’s also a great way to check that you understand what your doctor is telling you.

A patient had an active life before she became plagued with chronic pain and low energy levels. She was no longer able to participate in sports and other exercises with the same enthusiasm as before.

Eventually, she found a GP who diagnosed her condition as fibromyalgia, which involves chronic sore muscles, tiredness and mental fogginess, along with other symptoms.

“Make sure you stretch before you exercise,” said her doctor. “You might also want to reduce the intensity of your exercise regime for now, to see how your body responds.”

He handed her some brochures. “Here’s some more information you can read when you get home, and we can talk about it some more at your next appointment.”

“Okay, let me get this straight,” said the patient. “I should take some time away from my regular sports, which are fairly intense. Then I should report back to you on how I’m doing. Right?”

“Right. Your next appointment should be in two weeks.”

“Will that be my last visit?”

“No, I think I should follow up with you for the first while,” said the doctor. “There are all kinds of options to explore, such as attending support groups and changing your diet. For now, start with those brochures I’ve given you.”

If we are mindful listeners in patient-doctor exchanges, we will avoid frustration and misunderstanding, and experience better results.

© 2015 By Mary F. Hawkins. Talk to Your Doc: The Patient’s Guide is Published by Self-Counsel Press.

Now that you know how to speak to your doctor, discover 10 things you should never do before a doctor’s appointment.

Port-au-Prince, June 2010

The plastic door creaks on hinges rigged with paper and tape. Inside, the floor is plastic, with three sweaty concrete-block walls. There are a couple of operating tables and an anaesthesia machine. Two procedures could be done simultaneously, one with a ventilator and one with spinal anaesthesia. There are two oxygen-saturation monitors and multiple large cylinders of oxygen. The surgical beds are old and feel cold. Just as I am thinking that the room is well-lit, the lights flicker and dim.

I’m being taken on a tour of the trauma hospital at which I’ll be working for the next week. I’m volunteering here as part of the relief effort after the earthquake devastated Haiti the preceding January. Travelling with me from St. John’s are my wife, Allison (a pediatric emergency doctor) and my colleague Dr. Will Moores, a resident orthopaedic surgeon.

An overworked air conditioner hums somewhere. An anaesthesia machine beeps. Two Haitian nurses stand by in silence. All I can see is their eyes. Quiet eyes. Thousand-mile-stare eyes.

The anaesthesiologist on our team mulls over the machine, the general surgeon examines the trays of tools and our nurses look around the room. With Will, I begin poking around what would be our side of the room, looking for things we might need in the next few days. We leave the operating room and pass through a corridor into what used to be a birthing suite. It feels like a prison cell: four concrete walls, a small window and a small door.

There is no air conditioner, and it’s dark. There’s enough room for a single bed and little else. We could use this, but only for minor procedures such as suturing wounds. I leave the building, my nose stinging from the odour of formaldehyde.

The sun is cutting through the treetop canopy that covers the waiting area outside the operating-room building. It’s around 10 a.m. and it’s getting hotter by the second. We proceed to tour the rest of the facilities.

We quickly pass through the tent wards, listening like interns. The tents are jam-packed with people. Beds line one or both walls, leaving narrow corridors for nurses, doctors and families to pass along.

By a desk at one end of the second tent sits a single woman who appears cachectic—a word we use for emaciated—fatigued and quiet. From afar, she looks to be in her late 50s, but as we get closer, I see that she can be no older than 25. She sits in a chair by a bed with no sheets on it, the green plastic mattress fully exposed. She leans against the bed, and her white nightgown is falling off her now-visible skeleton. Her eyes are far different than the large, silent eyes I have seen in others. They are sunken and yellowed. She looks so alone. The bustle of the other tent is eerily absent.

Later on, after we see the other patients in the front of the tent, we step outside, and the local medical staff tell us that the lone girl has AIDS and likely TB. It’s horrifying to think of this poor girl’s fate—the disease, the accompanying solitude. Where is her hope? Her sunken eyes are ingrained in my mind forever.

As soon as rounds are over, the group disperses and the surgical team retreats to the corridors of the operating-room building. The team is nervous; you can sense the tension. We had only just met the local crew and I can barely remember their names. Yet here we are. Will and I sit, my legs bouncing rapidly up and down, as the next patient gets ready in the pre-op assessment area. We review the X-rays of the fractured hip and take pictures to document the case.

Everyone’s a bit anxious as we wait for the beginning of the series of steps that routinely lead to an operation. Allison is introduced to her translator for the week. Wicharly Charles is a young man of short, slim stature. He has a big smile and a bouncing energy that seem to lift everyone around him. Over the week, Allison and Wicharly become great friends, exchanging stories of family members and daily routines. Worrying about your kids feels universal in these moments. Wicharly eventually tells us that he is a painter, and at the end of the week he gives Allison one of his paintings. It still hangs in our kitchen in Newfoundland.

The blue booties and gown are on, the patient is placed on an ancient gurney, and we roll into the OR. The air conditioner is still not fully working, but it’s cooler here than in the other rooms. There is a procedure already under way, with the general surgeon repairing a trapped hernia on the table with the anaesthesia machine. The hip will be partially replaced on the other OR table, under spinal anaesthesia. This will be a first for me. It’s like a scene out of M*A*S*H where the surgeon at one table can talk to another across the way, nurses circulating to help both patients.

The gurney wheels screech to a halt and the patient is transferred onto the OR table and placed on his side. He winces with the move but is otherwise stoic. We firmly attach the patient to the table so he can’t move or fall, and the nurses do the prep. Will and I leave the OR to get ready. The masks go up, eye protection goes on, and as we stand in silence and scrub methodically, all the potential things that can go wrong rush through my head. Then there is a calm and all doubt leaves. One benefit of surgical experience is that, as gut-turned stressed as I am, my hands are steady. The knife confidently and firmly goes through the skin.

The surgery is over, and thankfully it was not a particularly tough one. But I still have this lingering excitement, as if it is the first time I have ever walked into an operating room. We replaced a patient’s hip in conditions I would never have dreamed possible. I keep repeating in my head: I can do this. I can do this. The heat reminds me of where I am, and there is no escaping the sweat. My scrubs are drenched, and it looks like I just showered in them.

Outside the OR, the lineup of patients stretches out of the courtyard. Allison and the rest of the team are working feverishly to push through as many patients as possible, and there’s a subset of patients with broken bones for us to triage.

We go through the cases and try to prioritize them as best we can. There’s no light box, so we hold X-rays up to the bright sun to illuminate their findings. Will and I know we have our work cut out for us with each broken, cracked or shattered bone we see. It’s a mess, and these people have been in severe pain for a long time with not so much as an Aspirin. We organize the list with the nurses and settle an order for the cases this week.

Next up is a man whose leg was broken in the earthquake. He has been struggling to walk for five months, and we think we can help him, and save the leg, with routine surgery.

Just as the tourniquet goes on, all hell breaks loose. We lose power. The local nurses dash out of the operating room, knocking things over in the dark, their screams filling the room and the hall. It gets worse. There’s a bleeding artery. We have no control, no light, no help. The room feels 10 times hotter. Panic. Blood moving in the dark. Focus returns before the lights. Muscle memory kicks in again. Deep breath. Keep it together till the bleeding is under control and the surgery is finished.

My focus is redirected as the team leader tells us we need to plan to leave the site in 10 minutes. There is an urgency, as we are all aware of the setting sun and what dangers—robberies and kidnappings among them—come with darkness.

We wend our way through the streets of Port-au-Prince, slowly tracing our way back up the hill to our home for the week. I’d fallen asleep, but I stir when the convoy pulls to a stop, and we proceed, with our armed escort, back into the heavily guarded house that feels more like a compound. We all sit exhausted. Tonight we will sleep on a bed under the hum of a generator and the scent of the mosquito net. I lather up in fly repellent, grab a slice of pizza and a cold beer, and within minutes I am nodding off again. The lights are still on, and everyone else is still awake.

As I drift off, some faces from the day revisit me. I wonder where the despondent girl with AIDS is tonight. What was her life like before all this? Where, if anywhere, does she find joy?

I think about some of the faces in the lineup outside the OR—the pain they are in, but the smiles they somehow manage to find. I have never witnessed hope in the eyes of patients like I have in Haiti.

The next day starts on a positive note. It feels like some order is making its way into the disorder. We wake, shower and descend toward the hospital. It takes about 45 minutes in the endless traffic, and we decide to set out earlier tomorrow to avoid the craziness. As we pull through the hospital gates, the funeral home is present in the background. We spend less time getting ready today and jump in right away as the team scurries to their duties.

Will and I begin rounds, checking on patients we operated on the day before. We still haven’t mastered expediently getting through patient rounds in tents; more time with patients means it takes far longer than we would like. It is now almost 11 a.m. and we have not operated yet.

The first surgery case is another hip replacement. The patient, we are told, has had a broken hip since the time of the earthquake and has been in a tent hospital since. He is lying there with a pin in his shin attached to a well-worn rope that hangs off the end of the bed with a bucket containing rocks at its end.

It’s primitive traction. It catches me off guard, and I find myself staring at it as if it’s a display in a medical museum. Traction is a form of treatment used years ago to prevent broken bones from moving so they would heal. It was usually rigged with a series of pulleys and wasn’t meant to be used for long—you could die from blood clots and infections. But this man had been lying flat on his back with the bucket pulling on him for months. If left much longer, it will pull him to his death.

His granddaughter is his bedside companion. She can’t be any more than 11, in a dirty dress, pigtails and the serious expression of someone far older. She did not leave her grandfather’s side the entire time.

Will begins explaining the surgery to the patient and the girl through an interpreter. Once we are finished the explanation, the granddaughter nods her head, there is a conversation in Creole, and they agree to go ahead. She walks alongside her grandfather while he is carried on the stretcher to the operating room, then waits outside in the courtyard.

Things go smoothly. The procedure is routine, and I’m confident in the outcome. Will and I escort the patient to the makeshift recovery room. We will wait until he is stabilized before making the journey through the collapsed portion of the hospital to get his post-operative X-ray done.

The surgery has taken a few hours, but as I walk out of the building, the young girl is still sitting there. There is no translator near. When she sees me, she leaps to her feet. I slow my pace and smile. She smiles and for the first time she looks her age. I give her the thumbs-up, and she sits back down with the smile still on her face.

All I can see is my own daughters sitting there, waiting for news from a surgeon. I get fidgety and I’m suddenly uncomfortable with my emotions, so I turn away and wait for Will.

We take the patient across the uneven pavement of the courtyard. On our way, other team members stop us to look at X-rays and hear of patients to be seen. We balance the stretcher carefully as we pass through a makeshift gateway that leads into one of the most damaged areas of the hospital, through a room where a large chunk of rubble has collapsed directly onto a hospital bed, the green walls still bright.

On the other side of the room lies another outside courtyard. Standing among garbage and rubble is one building that looks relatively well-preserved. It is the X-ray suite. Outside the doors, in the direct sun, are X-ray films hanging to dry.

There is a delay in the doors opening, as the X-ray personnel are busy listening to a soccer match on the radio. Eventually our patient is taken in, and the doors close. Around the corner, there’s a room that is collapsed except for one intact wall with windows. Peering through a broken window, I see that it is—or was—a cafeteria.

The disturbing image of life at the time of a disaster is replaced by the smile of the young girl as we return her grandfather to his bed. The smile, the hope in her eyes, the commitment to her grandfather—she smiles in spite of her surroundings.

I am buoyed by this case, and it sustains me for the remainder of the days of that first week-long trip.

Next, meet the Canadians who made a big difference during the pandemic.

Excerpted from Hope in the Balance, by Andrew Furey. Copyright © 2020 Andrew Furey. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Sky Fall

It began like any other May morning in California. The sky was blue, the sun hot. A slight breeze riffled the glistening waters of San Diego Bay. At the naval airbase on North Island, all was calm.

At 9:45 a.m., Walter Osipoff, a sandy-haired 23-year-old Marine second lieutenant from Akron, Ohio, boarded a DC-2 transport plane for a routine parachute jump. Lieutenant Bill Lowrey, a 34-year-old Navy test pilot from New Orleans, was already putting his observation plane through its paces. And John McCants, a husky 41-year-old aviation chief machinist’s mate from Jordan, Montana, was checking out the aircraft that he was scheduled to fly later. Before the sun was high in the noonday sky, these three men would be linked forever in one of history’s most spectacular mid-air rescues.

Osipoff was a seasoned parachutist and a former collegiate wrestling and gymnastics star. He had joined the National Guard and then the Marines in 1938. He had already made more than 20 jumps by May 15, 1941.

That morning, his DC-2 took off and headed for Kearny Mesa, where Osipoff would supervise practice jumps by 12 of his men. Three separate canvas cylinders, containing ammunition and rifles, were also to be parachuted overboard as part of the exercise.

Nine of the men had already jumped when Osipoff, standing a few centimetres from the plane’s door, started to toss out the last cargo container. Somehow, his backpack parachute’s automatic-release cord became looped over the cylinder, and his chute was suddenly ripped open. He tried to grab the quickly billowing silk, but the next thing he knew, he had been jerked from the plane—sucked out with such force that the impact of his body ripped a 76-centimetre gash in the DC-2’s aluminum fuselage.

Instead of flowing free, Osipoff’s open parachute now wrapped itself around the plane’s tail wheel. The chute’s chest strap and one leg strap had broken; only the second leg strap was still holding—and it had slipped down to Osipoff’s ankle. One by one, 24 of the 28 lines between his precariously attached harness and the parachute snapped. He was now hanging some 3.5 metres below and 4.5 metres behind the tail of the plane. Four parachute shroud lines that had twisted themselves around his left leg were all that kept him from being pitched to the earth.

Dangling upside down, Osipoff had enough presence of mind to not try to release his emergency parachute. With the plane pulling him one way and the emergency chute pulling him another, he realized that he would be torn in half. Conscious all the while, he knew that he was hanging by one leg, spinning and bouncing—and he was aware that his ribs hurt. He did not know then that two ribs and three vertebrae had been fractured.

Inside the plane, the crew struggled to pull Osipoff to safety, but they could not reach him. The aircraft was starting to run low on fuel, but an emergency landing with Osipoff dragging behind would certainly smash him to death. And pilot Harold Johnson had no radio contact with the ground.

To attract attention below, Johnson eased the transport down to 90 metres and started circling North Island. A few people at the base noticed the plane coming by every few minutes, but they assumed that it was towing some sort of target. Meanwhile, Bill Lowrey had landed his plane and was walking toward his office when he glanced upward. He and John McCants, who was working nearby, saw the figure dangling from the plane at the same time.

As the DC-2 circled once again, Lowrey yelled to McCants, “There’s a man hanging on that line. Do you suppose we can get him?” McCants answered grimly, “We can try.”

Lowrey shouted to his mechanics to get his plane ready for takeoff. It was an SOC-1, a two-seat, open-cockpit observation plane, less than eight metres long. Recalled Lowrey afterward, “I didn’t even know how much fuel it had.” Turning to McCants, he said, “Let’s go!”

McCants and Lowrey had never flown together before, but the two men seemed to take it for granted that they were going to attempt the impossible. “There was only one decision to be made,” Lowrey said later, “and that was to go get him. How, we didn’t know. We had no time to plan.”

Nor was there time to get through to their commanding officer and request permission for the flight. Lowrey simply told the tower, “Give me a green light. I’m taking off.” At the last moment, a Marine ran out to the plane with a hunting knife—for cutting Osipoff loose—and dumped it in McCants’s lap.

As the SOC-1 roared aloft, all activity around San Diego seemed to stop. Civilians crowded rooftops, children stopped playing at recess, and the men of North Island strained their eyes upward. With murmured prayers and pounding hearts, the watchers agonized through the mission’s every move.

Within minutes, Lowrey and McCants were under the transport, flying 90 metres off the ground. They made five approaches, but the air proved too bumpy to try for a rescue.

Since radio communication between the two planes was impossible, Lowrey hand-signalled Johnson to head out over the Pacific, where the air would be smoother, and they climbed to 1,000 metres. Johnson held his plane on a straight course and reduced speed to that of the smaller plane—160 kilometres an hour.

Lowrey flew back and away from Osipoff, but level with him. McCants, who was in the open seat behind Lowrey, saw that Osipoff was hanging by one foot and that blood was dripping from his helmet. Lowrey edged the plane closer with such precision that his manoeuvres jibed with the swings of Osipoff’s body. His timing had to be exact so that Osipoff did not smash into the SOC-1’s propeller.

Finally, Lowrey slipped his upper left wing under Osipoff’s shroud lines, and McCants, standing upright in the rear cockpit—with the plane still going 160 kilometres an hour, a kilometre above the sea—lunged for Osipoff. He grabbed him at the waist, and Osipoff flung his arms around McCants’s shoulders in a death grip.

McCants pulled Osipoff into the plane, but since it was only a two-seater, the next problem was where to put him. As Lowrey eased the SOC-1 forward to get some slack in the chute lines, McCants managed to stretch Osipoff’s body across the top of the fuselage, with Osipoff’s head in his lap.

Because McCants was using both hands to hold Osipoff, there was no way for him to cut the cords that still attached Osipoff to the DC-2. Lowrey then nosed his plane closer and closer to the transport and, with incredible precision, used the propeller to cut the shroud lines. After hanging for 33 minutes between life and death, Osipoff was finally free.

Lowrey had flown so close to the transport plane that he’d nicked a gash in its tail 30 centimetres long. The parachute, abruptly detached along with the shroud lines, immediately fell downward and wrapped itself around Lowrey’s rudder. This meant that Lowrey had to fly the SOC-1 without being able to control it properly and with most of Osipoff’s injured body still dangling outside.

Five minutes later, Lowrey somehow managed to touch down at North Island, and the little plane rolled to a stop. Osipoff finally lost consciousness—but not before he heard sailors applauding the landing.

Later on, after lunch, Lowrey and McCants went back to their usual duties. Three weeks later, both men were flown to Washington, D.C., where Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox awarded them the Distinguished Flying Cross for executing “one of the most brilliant and daring rescues in naval history.”

Osipoff spent the next six months in the hospital. The following January, completely recovered and newly promoted to first lieutenant, he went back to parachute jumping. The morning he was to make his first jump after the accident, he was cool and laconic, as usual. His friends, though, were nervous. One after another, they went up to reassure him. Each volunteered to jump first so he could follow.

Osipoff grinned and shook his head. “The hell with that!” he said as he fastened his parachute. “I know damn well I’m going to make it.” And he did.

This article first appeared in the May 1975 issue of Reader’s Digest.

In the mood for more heart-stopping survival stories? Check out these other true tales from our Drama in Real Life section.

Look. Listen. When you’re a busy career woman and mom of 17 who’s always on the go and just trying to have it all, grocery trips need to be quick, efficient affairs. I’ve learned to anticipate well in advance that at some point, my 284-week-old triplets will once again want to make ferret-shaped cupcakes. And I’ve learned to be prepared. Or so I thought.

I can’t explain how it happened. I remember being in the grocery store. I remember grabbing the bag of flour off the shelf. No I did not, quote, “HAVE TIME” to check if the bag said “All-Purpose,” “Some-Purpose,” “Undisclosed-Purpose” or “Still Searching For Its Purpose.” But when I got home and dumped my groceries on the kitchen island, it became clear: the bag said “No-Purpose.” It was one of the most chilling moments of my adult life, perhaps second only to the night my three toddlers informed me in unison that they needed to make ferret-shaped cupcakes. They were standing over my bed when they said it. It was 4:12 a.m.

Okay, so: no-purpose flour. Could just be a mistake on the packaging. Why would such a product even exist if it had no purpose? My first impulse was to disregard the label entirely. I see now how deeply foolish that was.

I quickly whipped up a test batch of cupcakes alone in the kitchen. But when I took them out of the oven, the flour had become rock hard. It cost me 91 per cent of my teeth to make this discovery.

Whilst sitting in my dentist’s waiting room, I solemnly promised a terrible oil painting of some boats on a wall before me that I would not panic just yet. Okay, so maybe the flour had “no purpose” within the realm of baking, but surely it had a purpose in the realm of, like, the world. I didn’t want to just throw it out.

I rushed home with a brilliant, waste-conscious idea: I would use the remaining bag of flour as a doorstop. The kitchen door is always swinging and flinging about, and this was the perfect solution. Except, it wasn’t at all. I’m dismayed to report that the bag disintegrated within 10-12 business minutes and the flour seeped out into a soft and useless pile on the linoleum.

I attempted to use the remnants of the pile to make some homemade playdough for the kids, but the nanosecond the substance was ready, it formed itself into letters that spelled “GET LOST.” It then evaporated instantly before my eyes. No, I have not been enthusiastically celebrating legalization; this really happened.

I then returned to the store and purchased a new bag of no-purpose flour, determined to start fresh and use it as a hand weight during my home workouts, but it inexplicably became lighter than the air itself.

At the time of this writing, there is no known purpose for this flour. I have now quit my job as a popular horse psychic and devoted the remainder of my natural life to the pursuit of proving the flour’s purposelessness to any and all doubters.

How is that working out so far? Let’s just say it’s time to strike “dry shampoo??” off my list because I tested that theory 10 minutes ago and am now legally bald as a result.

Next, check out the best Canadian jokes ever!

The peaceful transfer of power is one of the fundamental tenets of any democracy. When the United States’ first president George Washington’s second term was over, he voluntarily stepped down and John Adams, who had won the election, took office.

“That was not a constitutional requirement at the time,” says Jon Michaels, a professor in the UCLA School of Law, author of Constitutional Coup: Privatization’s Threat to the American Republic, and noted authority on constitutional law, presidential powers, government ethics and conflicts of interest. In fact, it’s still not. The 20th Amendment stipulates that a president’s term—outlined in the Constitution as a four-year period—ends at noon on January 20 at the end of those four years. But, the Constitution does not spell out how it is to be handled. Rather, it’s a matter of tradition.

When Thomas Jefferson ran a politically heated campaign against John Adams in 1800, the Electoral College was tied and the outcome had to be decided by the House of Representatives. Even so, once the matter was settled, Adams peacefully vacated the office, setting the precedent for the next 220 years.

Challenging the norms

On September 23, 2020, President Donald Trump wouldn’t commit to following the two-centuries’ old custom when asked during a news conference. It wasn’t the first time he suggested as much: In March 2018, he praised China’s move to abolish presidential term limits, joking that the U.S. might “have to give that a shot someday.”

Now that the election is less than a month away, such rhetoric is being taken more seriously. Russell Riley, PhD, professor and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the Miller Center, a nonpartisan affiliate of the University of Virginia that specializes in presidential scholarship, notes that questions of what happens if a president should refuse to leave office involves “an extraordinarily arcane area of presidential politics.”

Presidential protocol

There is a proscribed sequence of events that happens when the incumbent president’s term expires at the dot of noon on January 20. These include:

- The nuclear codes, which allow the president to order a nuclear attack, expire. The military aide who carries the “nuclear football” containing the codes leaves the departing president’s side and joins the president being inaugurated.

- The U.S. military switches its allegiance from the outgoing president to the incoming president. Any military orders issued by the outgoing president would be refused. Any officers who obeyed such orders could be arrested and tried on charges of mutiny and sedition.

- Likewise, the Secret Service moves to protect the new president and abandons the electoral loser, except for a small unit that will protect him and his family for the remainder of their lives, one of the perks presidents get to keep after leaving office.

These actions make it highly unlikely that a president could go rogue and refuse to leave office. Even if he tried, the new president’s acting attorney general could draw up arrest warrants for charges ranging from criminal trespassing to insurrection.

Legal challenges

That doesn’t mean a candidate couldn’t try to steer the election outcome, or delay its determination, through other means.

If the popular vote indicates that a candidate has won the election by a narrow margin, the results could be contested with lawsuits and other manoeuvres. Some would say Trump has laid the groundwork for this by challenging the legitimacy of mail-in ballots, which are expected to comprise more than half of this year’s votes. If election night returns show Trump in the lead—a distinct possibility, as surveys show Trump supporters are more likely to vote in person than Biden backers—he may try to claim victory and stop the counting of mail-in ballots.

Meanwhile, Republican and Democratic parties have already launched dozens of lawsuits each, and other groups have filed hundreds more, primarily centering on mail-in ballot technicalities. Many are hopeful attempts to answer questions before the election, but it’s likely many legal questions will remain well into November and beyond.

In the event of a slim popular vote margin, a candidate could also try to leverage the Electoral College and its deadlines. Electors must be chosen no later than 41 days after Election Day. On that date, which is December 14 this year, the electors meet to cast their votes—typically for the candidate who won the popular vote in their state. Then, on December 23, each state submits an electoral certificate to Congress, and on January 6 Congress counts the votes.

However, it’s not always so cut-and-dried. If the electors are selected after December 8, the so-called “safe harbour” date, their validity—and their votes—could be challenged.

Another consideration: In 17 states, electors are not required to vote for the winner of the popular vote. Candidates could pressure those state legislatures in several of those states—including the hotly contested Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan and Wisconsin—to certify electors who would vote in their favour. If governance of those states is split—say, a Republican legislature with a Democratic governor—states could end up submitting conflicting electoral certificates to Congress and muddying the vote.

The Electoral Count Act

If that happens, the Electoral Count Act would be triggered. This legislation was created after the 1876 Rutherford B. Hayes–Samuel J. Tilden contest, when three states submitted conflicting electoral certificates, preventing an Electoral College majority. The ECA states that in such circumstances, the two houses of Congress vote on which slate of electors to approve. With the Senate currently under Republican control and the House of Representatives currently under Democratic control (though that could change by the time Congress is seated on January 3), a stalemate is possible. However, the act is quite vague on how different scenarios should be resolved, and challenges to the law are expected. The issue could even be sent to the Supreme Court. But, Riley takes issue with this approach, especially given the current rush to confirm a new SCOTUS justice before Election Day. “No justice appointed under these circumstances under any prevailing standard of judgment should agree to issue a ruling on this election. Justices recuse themselves when they are parties to issues coming before the court,” Riley says.

The Presidential Succession Act

This legislation, crafted in 1947, outlines what happens when the office of the president is vacant. If no president or vice president can be selected before January 20, when the current president’s term expires, the Speaker of the House becomes acting president until the situation can be resolved.

According to Riley, this nearly happened in 2000 when voting irregularities in Florida caused election results to be contested. Dennis Hastert, then Speaker of the House, told Riley in a later interview, “The CIA would come and start to brief me. I was going to be the temporary president if the decision wasn’t made by some date in January.” Nevertheless, the situation was resolved and no one except the vice president has ever succeeded the president since the act was signed into law.

Democracy prevails

Riley remains optimistic that none of this will come to pass this year, thanks to the much-maligned Electoral College. “One of the virtues of the Electoral College is that it has the effect of exaggerating the popular vote and accentuates the authority of the person who wins,” he explains. As an example, he says a 4 or 5 percent popular vote win can look like an Electoral College rout. “However in instances where there is a question about the outcome of an election, it cabins the contest to a very narrow area.” He predicts that in the vast majority of states, it’s going to be reasonably clear who won in the upcoming election. “The contest is going to come down to two or three ugly situations.”

But, as Riley notes, many Republicans in power, as well as Democrats, are “openly saying there needs to be a calm and reasoned transfer of power…It helps that you’ve got people in both parties who are saying they’re going to pay careful attention to these things and try to broker a peaceful transition.”

The fact that we don’t have explicit rules or tools to enforce the unwritten pact guaranteeing a peaceful transition is a testament to our collective integrity, Michaels says. “If we have to add it now, it will forever mark this moment as the nadir of our republic.”

Sources:

- Jon Michaels, a professor in the UCLA School of Law

- Russell Riley, PhD, professor and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the Miller Center

- Pew Research Center:”Americans’ expectations about voting in 2020 presidential election are colored by partisan differences”

- Lawrence R. Douglas, a professor in Amerhest College

- The Hill: “Trump on Chinese president abolishing term limits: ‘Maybe we’ll give that a shot someday'”

- CNBC.com: “Trump won’t commit to a peaceful transfer of power if he loses the election”

Next, find out how the US election will decide the fate of this caribou herd.

As a kid, Janelle Niles loved to watch Just for Laughs on TV at home in Truro, N.S, not far from her Sipekne’katik First Nation community. If she was able to laugh at something, she felt, it couldn’t hurt her or be used against her. Now a 33-year-old massage therapy student and hospital security guard in Ottawa, she’s channelled her childhood obsession into a moonlighting gig as a stand-up comedian.

But she was disappointed to be the only Indigenous comic on the bill most nights—and it didn’t take long for her to grow tired of being the “token.” Niles admired the comedian Kenny Robinson’s long-running, all-Black Yuk Yuk’s Toronto set, Nubian Show, and wondered, “Well, where’s ours?”

First, she gave her all-Indigenous show a name. Got Land? is a nod to the Land Back movement, which is, in turn, part of a complex conversation around what it would mean to return colonized territory to Indigenous peoples. Next, Niles recruited talent. Her roster now counts 12 emerging and established Indigenous comics, such as Don Kelly of APTN’s Fish Out of Water.

Last September, Niles stood up inside Eddy’s, an Ottawa diner, and welcomed the audience to her inaugural show. The night sold out: she had to turn people away at the door. Looking around, she joked, “We’ve got to kick out all the white people to make room for the Natives.” The room erupted in laughter—and the rest of the evening only grew more raucous.

Since its kickoff, Got Land? has hosted even larger crowds at both Algonquin College and Carleton University, and was set to do the same with two shows at Ottawa University before COVID-19 put plans on hold.

Mélissa Lambert-Tenasco, a 27-year-old executive assistant who attended the first show and is now a diehard fan, will be in the audience when the comics are back on stage. “Laughter is big in our communities,” she says, “and it was really nice to laugh with a bunch of Native people—it’s nice to be making the jokes for once.” And while the show is “for our people, with our people,” Niles also wants Got Land? to help boost Canadians’ general knowledge about Indigenous culture. “It’s a safe environment for us to engage with each other, have an exchange, gain some knowledge,” she says, “but also tell those harsh truths.”

One of Niles’ first—and most popular—bits is a parody of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” in which she changes the lyrics to tell the audience that, in fact, the land belongs to Indigenous people. “This land is my land, this land ain’t your land,” she sings, mimicking the tune of the familiar folk song. “You pretty much stole it, right out of our hands. You made my people sign a treaty which we didn’t fully understand.”

Niles says her next step is to bring Indigenous comedy into the mainstream. She wants to see Indigenous comedians share the stage next to legends like Dave Chapelle and Bill Burr. Her own comedy dream is to be featured on Just for Laughs.

“With Got Land?, I’m trying to pull everyone together,” says Niles. “As I make my way through comedy, I want to bring everyone with me.”

Next, check out the best jokes from Canada’s top comedians.

A chance meeting

I first noticed her one evening in October 2018. A shadow, she was without shape, at first. Then, I saw clearly that this was one big bird who’d come calling at my local park in downtown Toronto.

I was trepidatious, and felt compelled to find out more. Being so out of place, alone and, well, so large, she became more than a passing focus; she became an obsession. This was not a basted Butterball, this was a wild thing with considerable mojo.

Thanks to repopulation efforts in the 1980s, eastern wild turkeys can be found across southern Ontario. But, what was Rose doing in the middle of Toronto? What did she want? Some Indigenous peoples consider wild turkeys to be messengers and teachers. Turkey feathers are used in ceremonies and the bird ranks highly in its spiritual significance. What was her message to me? To us?

I was about to retire after many years as the founder and chief executive of a child welfare agency, and felt just a little lost for it. I fixated on what Rose might mean to me. Was she an old bird without purpose who chose to retire to a place without pesky coyotes and the stresses of everyday turkey life in the wild? Or, was she lost?

Maybe she had been heading somewhere, following those old pathways that wild things know but are long forgotten by us. My house sits on the bank of a buried creek that runs audibly beneath 12 feet of infill. Had she been following a primordial highway of waterways and old ravines down to the lake and beyond? I could not accept her visit was pure chance.

Rose was with us throughout the winter. She was solitary. Notwithstanding being surrounded by four kinds of squirrel and, once, a well-groomed rat, she was very much alone. I am sure my empathy for her springs from a realization of the potential isolation that can accompany our golden years.

On the more fundamental level, I wondered what she could possibly be eating in this downtown park. I bought a huge bag of peanuts, which turkeys apparently like to eat, and started feeding her. She seemed grateful, coming to me in the early morning with an eerie cluck-and-chirp combination. She didn’t walk, but sort of glided toward me.

As winter arrived, the park became encased in ice. She not only coped with the ice, but managed the incredibly cold temperatures, too. Every evening she would elevate herself into the trees. Her flight was a kind of slow motion dream sequence, threading her way through the tangle of branches to a selected limb. She would alight just right. Pure grace, a bird ballet. Once there, she would puff herself into a feathery ball, tuck her head into her wings, scrunch down covering her legs and wait out whatever the worst of winter could bring.

One popular bird

Others noticed her as well. I witnessed scores of passersby utterly enchanted by her presence. They’d curb their dogs and smile, uplifted by the moment. Everyone loved her. But nobody loved Rose more than the children from the elementary school adjacent to the park. They are the ones who named her Rose. Whenever Rose was present kids would gather, at a distance, wide-eyed and nervous. For a good many, this great bird was perhaps the only truly wild thing they had ever encountered, and they were filled with wonder and enchantment.

Some would approach too closely for her comfort. With that, Rose would face them, flare her wings, ruffle her feathers, feign flight and the kids would take off, screaming in delight. Had she chosen to really pursue them, she could reach over 40 kilometres an hour on the ground and 80 in flight. Those kids wouldn’t have a chance.

Early in my encounters with Rose, I called the City of Toronto. I wanted to know if they had some kind of turkey program, something supportive perhaps, maybe even humane removal to a safer place. They had nothing and instead recommended I call a pest control company. I was indignant. Rose was no pest and the thought of her being classed as such renewed my commitment to help her along. I believed this bird to be a gift from nature, the Creator, and if we would only listen, perhaps we could get some good advice.

Turkeys raised for food are nothing like Rose. Sadly, the commercial birds ceremoniously pardoned by the U.S. president every Thanksgiving usually die within the year. They are descendants of a Central American strain taken to Europe and returned much modified to our dinner table. Only distant cousins to Rose, they demonstrate the limits of our scientific ways.

At Thanksgiving, Rose was impossible to find. She spent Christmas disguised as a squirrel’s nest about 40 feet up. Smart girl.

She had, if she’ll pardon these words, tremendous pluck. Seeing her balled up in the tree braving the storms was inspiring, but also a bit depressing. If she was a messenger, the message wasn’t that clear. Perhaps she was there to inspire environmental stewardship. I felt it—seeing this tough beauty, not so far away from Yonge Street, walking around like she owned the place.

When spring came, Rose flew away. In a sense, I was relieved to see her go. I can picture her now with her “Tom” and a nest of chicks. While I’m not convinced she won’t be back—she loved those peanuts—I felt I did a good thing to help her along.

I wasn’t Rose’s only friend. Truly, she was no beauty with her snoop, wattle and multicoloured, wrinkly head. I think we all loved her because she gave a heartfelt message of hope to those of us who are worried about this natural world. Rose tells me we still have a chance. We are buoyed by her because she affirms the strength and resilience of nature. Thanks, Rose.

© 2019, Kenn Richard. From ‘’The Wild Turkey That Captured My Heart,’’ The Globe and Mail (July 18, 2019)

theglobeandmail.com

Next, read the strange story of the flamingo that ended up in the Ottawa River.

Horse of a Different Colour

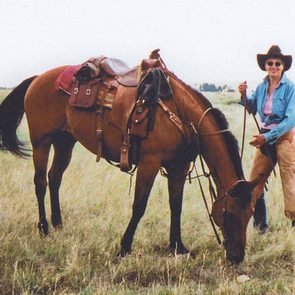

Last summer, I put my old horse in the ground. But there’s way more to the story than that. Roany spent 39 years on the planet, and 25 of those were with me.

The first thing I noticed about him were his kind eyes; the second was his size—just under 17 hands (1.72 metres) at the shoulder. The Santa Fe cowboy who sold him didn’t tell me much, but within days I came to understand Roany’s intensely good nature. Each morning when I went out to feed him, he greeted me with a just-happy-to-be-here chortle.

He was as solid a trail horse as I’ve ever ridden, never flinching in big wind or while crossing water, or even when two mule deer, hidden by some willows, leaped in front of him. He was so bombproof that the county search-and-rescue team enlisted his help a few times a year to find and deliver a wayward hiker.

I bought Roany the same year I moved to a ranch in Creede, Colo., because Deseo, my alarmist Paso Fino horse, decided it was the scariest place he’d ever been. I counted on Roany to keep the whole barnyard calm, not just Deseo and the miniature donkeys but also the ewes and lambs, the recalcitrant rams, the aging chickens and me.

Like all roan horses, Roany’s coat marked the changing of the seasons. In the dead of winter, he was burgundy with tiny white flecks. In March, he would shed to a dappled grey with rust highlights. By midsummer he was red again, but not as rich. And when his heavy coat grew back in October, he was solid grey for most of a month.

I stopped riding Roany when he turned 33 because I thought my old friend deserved a lengthy retirement, though he stayed strong until a few months before his death.

His decline started with a bout of lameness in April and a longer one in May. By late June, he was limping more often than not. When Doc Howard came for a ranch call, he said, “There’s a number associated with this lameness, Pam, and it’s 39.”

I did the things there are to do: supplements, an ice boot, various anti-inflammatories and painkillers. We’d had very little snow and no spring rain, and for the first time in my tenure the pasture stayed dormant all summer, the ground extra hard on sore hooves.

Roany loved nothing more than the return of the spring grass, and it seemed radically unfair that in what was looking to be his last year, there wouldn’t be any. I watered, daily, a thin strip of ground between the corral and the chicken coop and called it Roany’s golf course.

He had some good days there, but mostly he hung around the corral. That summer, between my fiancé, Mike, my ranch helpers, Kyle and Emma, and me, Roany hardly had a moment’s peace. We iced his legs and groomed him twice daily, mixed canola oil into his grain to help keep weight on him, and hugged him constantly.

He seemed bemused by all the attention. Every time we set the water in front of him, he took a giant drink, and I suspect it was more for our sake than his. One day, Kyle, not knowing I was out there, set a bucket down next to Roany not three minutes after he had drunk three-fourths of a fresh bucket for me. Roany looked at Kyle for a minute, glanced over at me, then lowered his head to drink again.

Roany was stoicism defined. As his condition worsened, he learned to pivot on his good front leg—and he would, for an apple or a carrot or to sneak into the barn to get at the winter’s stash of alfalfa. He blew bubbles in his water bucket because it made me laugh, and he would sometimes even give himself a bird bath by splashing his still-mighty head.

I also knew that just because he could handle the discomfort it didn’t mean he should. He had been so strong so recently, a force of nature thundering back and forth across the pasture. There was no chance I was going to ask him to make another winter, but as long as he was hobbling to his golf course and chortling to me each morning, it seemed too early to end his life.

A sweet goodbye

Among Mike’s many gifts is a deep intuition about the suffering of people and animals, so I paid attention when he said, on a Monday night in mid-August, “This is entirely your decision, but if you want to put Roany down this week, I could take Wednesday afternoon off.”

The next day I saw a slight downturn in Roany’s condition. He ate his food, drank his water, and stood for his treatments, but there was something a little lost in his kind eyes. I called Doc and made the appointment for Wednesday afternoon, with the caveat that I could cancel if Roany’s condition improved or I lost my nerve.

By Tuesday night, Roany was swaying, just slightly. He ate, but with a little less enthusiasm than usual. I went out to check on him at 8 p.m. and then at 10. The moon was bright and the coyotes were singing. Even by this light I could see that Roany was holding his body like he didn’t feel right inside of it.

I woke at 4:30 with the kind of start that always means something has happened. I grabbed a flashlight and rushed to the corral, but Roany wasn’t there, nor on his golf course, nor in the yard.

I called his name and heard hoofbeats coming hard across the pasture. I indulged the fantasy that after weeks of suffering he was miraculously cured. Then I heard Deseo: my hot-blooded alarmist, my early-warning system, my tsunami siren. He skidded to a stop and butted his head against my chest, seeming to say: About time you got here.

I started out with Deseo beside me, heading for one of Roany’s favourite spots at the back of the property. When I turned at the quarter pole, Deseo whinnied again: Not that way, human. By this time, Mike was crossing the pasture to meet me. Deseo whinnied again, and we followed him to another favourite spot—a shady stand of blue spruce at the base of a hill. It was the first time since last summer that Roany had been out that far.

He was still standing when I got there. But the minute he saw me, he went to the ground. He curled up like a fawn, and I could hear that his breathing wasn’t right. Mike and I sat beside him and petted his handsome neck.

Above us, stragglers from the Perseid meteor shower, which had peaked over the weekend, streaked the blackness. Pegasus, the biggest horse of all, galloped across the sky. We listened to Roany’s breathing and the coming of dawn. Deseo stood nearby, head lowered.

Roany stretched out his long legs and put his head in my lap. I thanked him for taking good care of the ranch animals, including the humans, including me. I told him I’d be okay, that we’d all be okay, and he could go whenever he needed to, but he went on taking one slow breath after another.

Kindness of others

On one of Roany’s first bad days, a compassionate horsewoman named Debbie innocently asked me how I was. My answer was no doubt more than she’d bargained for, but on that day she became my adviser in horse eldercare and pain relief.

I told her my fears: I had made difficult decisions with beloved dogs, but the length of a horse’s life and the sheer size of its body makes everything trickier. Debbie promised that, when the time came, she would send her husband out on his track hoe to dig the hole, never mind that they lived off-grid more than 30 kilometres away.

Now, I called Debbie to say I thought we were close. Then, I called Doc to say I thought we might not need him. It was finally daylight, but the sun hadn’t risen. Mike and I were shivering, so he slid into my place to hold Roany’s head and I ran to get sleeping bags. When I got back across the pasture, Roany’s head was still in Mike’s lap, but now he was struggling for breath.

“Touch him,” Mike said. I knelt and put my hand on his big red neck. Roany took one breath and then another and then the last breath he would take forever. “I think he was waiting until you got back.”

A moment later, the first rays of sun came over the hill, turning the sky electric. I crossed the pasture one more time to get Roany’s brushes to groom him for burial. Debbie’s husband, Billy Joe, had a dozen things to do that morning, but he arrived at the ranch not long after I called.

I don’t know Debbie very well, and Billy Joe hardly at all, but as much as anything else this is a story about the way people in my town care for one another. When I tried to pay Billy Joe for his time, or even for gas, he shook his head and said, “An old cowboy doesn’t take money to bury an old horse.”

If there is such a thing as a good death, Roany had one. It was almost as if he had heard Mike’s offer and said, All right then, Wednesday, and how about in that stand of spruce on the other side of the hill? I’ve always said Roany was a horse who never wanted to cause anybody trouble. He remained that horse till the last second of his life and beyond.

Late that night, I watched the Perseids burn past my window and imagined my old Roany up there, muscles restored to their prime, and his shining burgundy coat alongside the white of Pegasus, both of them with their heads held high, and galloping.

Outside (May 2019), Copyright 2019 by Pam Housons, Outsideonline.com.

Next, find out what it’s like photographing Alberta’s wild horses.

The year 2020 will certainly go down in history as one of the most challenging on record. Many of us are still trying to wrap our heads around the new normal, and trying to stay healthy both physically and mentally. And while the situation may not seem quite as dire as it was back in the spring, fall may bring new challenges. It’s clear that social distancing is still the responsible and ethical approach to keeping numbers down and preventing our hospitals from becoming overwhelmed.

That said, we’re all missing life before COVID-19. It’s so hard to be socially distant from our friends and family, but staying apart is what’s keeping us healthy. Fortunately, there are things you can do to make this time feel less isolating and bring a greater sense of peace and connection.

Start each day with something for you

Practising self-care is a great way to prioritize your mental wellness. Try to start your day on a positive note. Write in a gratitude journal or practise meditation. Listen to an uplifting audiobook or a podcast. Even if it means waking up 30 minutes before the rest of your family, making these little changes can help set the tone for your entire day. (Here’s what might happen when you start meditating every day.)

Limit your time on social media

It seems counterintuitive to limit your time on social media, but despite having your entire network at your fingertips, constant scrolling can lead to higher levels of anxiety and sadness, and heighten your sense of FOMO (fear of missing out). Dedicate a few social media “check-in” times throughout the day to stay in the loop, but otherwise try to stay off your phone and use your screen time more purposefully. (You can even plan “watch parties” around your favourite Netflix series with your friends!)

Be social

We’re all getting weary of looking at our friends and loved ones on a screen, but this is our reality and we need to make the best of it. Make an effort to maintain your virtual get-togethers, because without them, the risk of feeling lonely and isolated increases. Go old school and talk on the phone, or have a glass of wine with a friend over FaceTime. Social interaction, whether virtual or in person, will help you feel less alone and more connected with those around you. It’ll also provide you with support if you’re having a difficult time coping. (Read the inspiring story of how COVID-19 taught one man how to be a better friend.)

Stay physically active

Doing exercise releases endorphins and serotonin, which has a significant impact on mood. Going for a walk with a friend is a great way to combat loneliness. Playing tag in the yard or a park with your kids or grandkids, or even challenging yourself with push-ups or an exercise app will also help elevate your overall mood and energy levels. (Lost the spring in your step? Find out how to make walking less boring.)

Act with purpose

If you do wind up with an extra moment to yourself, try to focus on the things in your life that make you feel good. Take charge and do tasks around the house that give you a feeling of purpose. Set a daily to-do list that allows you to see what you are accomplishing. Clean out your closet, read a favourite book series, sign up for an online course or put on your chef’s hat and experiment with a few new recipes. (Here are 25 ways to relax that don’t cost a cent.)

Seek professional help

If your feelings of loneliness and isolation persist, find a therapist who provides video or telephone sessions. These are great alternatives for people who want to practise social distancing but feel like they would benefit from therapy during this stressful time.

Know you are not alone

There is not a person in the world who is unaffected by COVID-19, so try to find some comfort in the idea that we’re all in this together. Also, do your best to reframe the experience into something more positive and productive. Count yourself lucky to have some bonus time with family, get things done that you haven’t had time for and challenge yourself with new fitness activities. Above all, if you’re struggling, don’t keep it to yourself. A friendly face is always just a video chat away.

Now that you know how to cope with loneliness during COVID-19, learn to spot the signs you could be suffering from high-functioning depression.