Lost on Burke Mountain

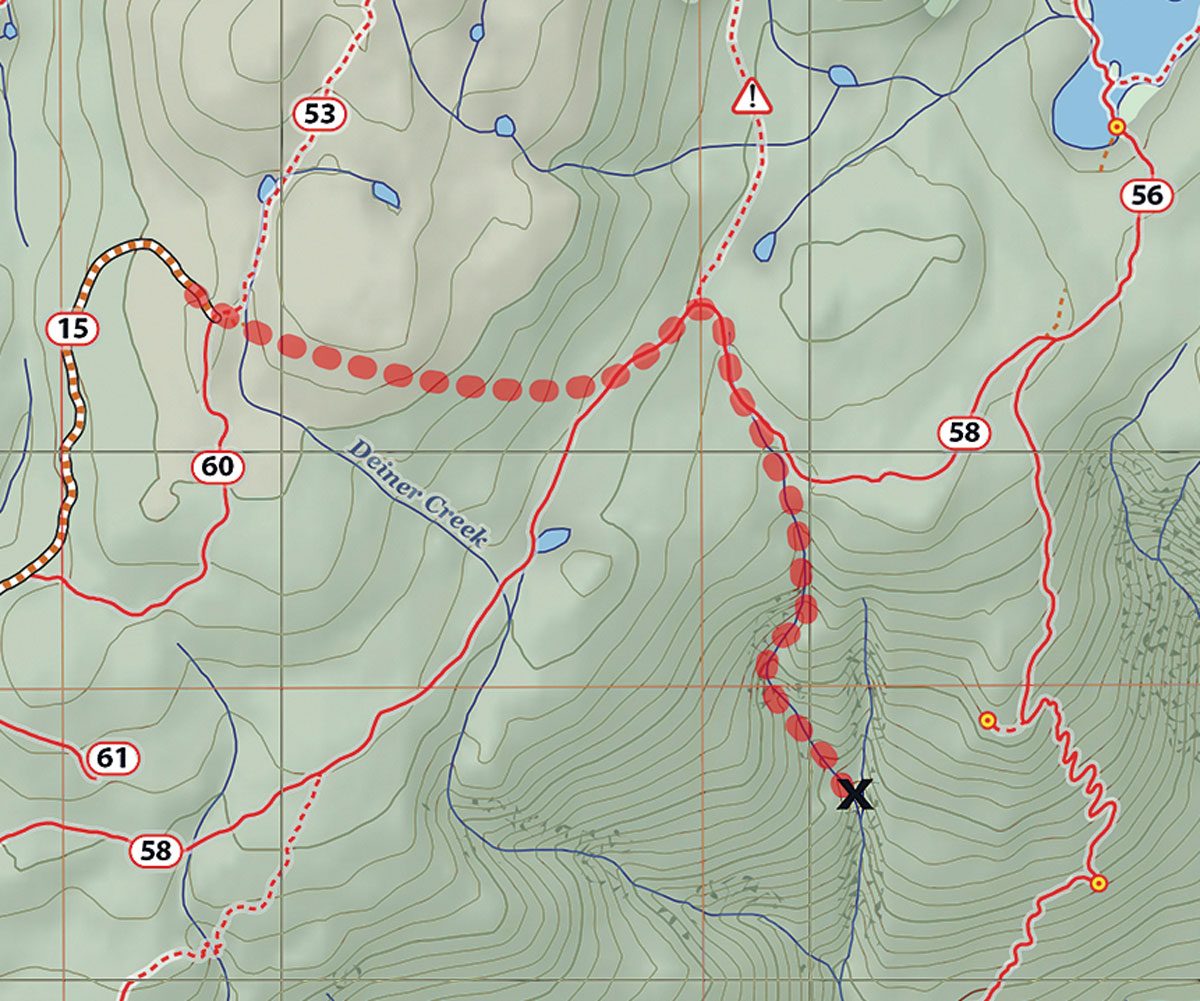

Brandon Hoogstra had hiked Burke Mountain, near his home in Coquitlam, B.C., once before. He knew the route to the summit and an abandoned ski lodge.

But he and his wife, Claire, objected when their two eldest, six-year-old Ezri and seven-year-old Oliver, begged to join him for another hike in May 2019. The route was too long—at least 11 kilometres. Even if the weather was nice, they’d surely get tired. And while she loved her husband dearly, Claire worried about him—Brandon is on the autism spectrum, socially awkward at times, highly sensitive and prone to choices that might seem erratic.

The Hoogstras were new to town. Thirty-five-year-old Claire and 34-year-old Brandon had both grown up in the Atlanta area. Wanting to experience life outside the U.S., they’d lived for a couple of years in Chiapas, Mexico, where Brandon worked at a water-treatment plant. In 2018, they decided to give Canada a try, and rented a basement suite in Coquitlam for themselves and their four kids (Gabriel was 22 months, Holly six months).

Ezri and Oliver were so keen to climb the mountain that the parents finally relented. Just after 8 a.m. on a beautiful Sunday morning, they set off. Brandon’s backpack held his phone, Clif bars, packets of apple sauce, apples, water bottles and fishing gear. They’d refill the bottles in the clear streams up the mountain.

Brandon had planned a varied route up the mountain. The winding ascent was fun and uneventful. Near the top, thick snow blanketed the trail. Excitedly, the kids raced across the crusted surface.

At the summit, Oliver and Ezri shared the second-last Clif bar while Brandon looked around. His phone showed 1:30 p.m. and no reception. They’d rest for an hour, he decided, then head back to Claire and the babies.

When the kids started down the far side of the slope, Brandon said, “You guys really want to find those fishing lakes, don’t you?” He’d identified them on Google Earth.

“Oh, yes!” Ezri said.

So they took an unfamiliar route down the other side of the mountain.

By the time Brandon realized the path they were on had become an animal trail alongside a stream, it made sense to keep following it. When the stream reached a cascading waterfall, they clambered carefully down the slippery rocks to the pool below.

The stream sang to them, and they kept following it down. The day had been bright and beautiful. Mid afternoon, when the sun disappeared behind heavy grey clouds, they suddenly felt disoriented, cold and hungry. Brandon tried to light a fire, but couldn’t ignite the wet twigs.

They decided to continue hiking down. For half an hour they cautiously descended until they reached a sheer cliff edge. The stream became a noisy, six-metre waterfall. Brandon cursed himself for taking an unknown route down. He hadn’t studied this area and he didn’t have a map. Ezri took his hand. She, like Brandon, had a unique way of processing the world. “Dad,” she said, crying, “I love you, and I don’t blame you for getting lost. You’re my dad, and you’re nice.”

“Babies,” he said, “hopefully there are no more waterfalls. The Lord will guide us.”

They held hands as they carefully descended. Finally, Brandon said, “It’s too steep. We’ll have to slide on our butts.”

Still holding hands, they inched down the slope. Tree trunks were rest stops. Fir saplings, their roots sunk deep in the rock, made handholds. It worked well until they reached a sheer, 10-metre drop and the stream became a deafening waterfall. Mist soaked them as the water raced over a tumble of boulders.

“Easy-peasy,” Brandon said, like a character from the kids’ favourite movie, Horton Hears a Who. They made their way, inch by inch, until Oliver slid on a loose rock and all three of them went flying.

Mid-air, as if in slow motion, Brandon watched his son’s head smack a boulder. Then his own head hit rock. Stunned, ears ringing, he realized he’d split open his forehead.

“Help me, Dad!”

Oliver, in the water, was being swept away. Brandon desperately lunged and pulled him to safety. One of Oliver’s shoes floated off.

Brandon wiped blood from his eyes and gathered his senses. Was anyone hurt? Oliver, crying and shivering, seemed okay. Ezri was wailing, but she too appeared uninjured. Brandon himself, though disoriented, didn’t feel anything worse than the gash on his forehead. The backpack was lodged in the rocks six metres away. He saw no use trying to retrieve it.

After calming the kids, he said, “Stay here while I look for a way out. I’ll be right back.” As he worked his way downstream, the terrain became less steep. It seemed they were through the worst of it. He climbed back up to the kids to share the good news.

“I’m missing a shoe, too,” Ezri said.

“Honeybunch,” said Brandon, “if you guys can’t have both shoes, I don’t need mine either.” He pulled off his shoes and threw them as far as he could.

On they went. The slope was gentler at first, but when they emerged onto a gravelly plateau near a 30-metre waterfall, their plight was suddenly, painfully clear. The air was cold and getting colder. They were wet and exhausted. Brandon had no idea where they were.

This plateau was a safe spot. To save the kids, Brandon realized, he had to go for help.

“Oliver, Ezri,” he said, taking off his grey hoodie and draping it around them, “stay here, no matter what. Do you understand? I’m going to get friendly people who’ll pull you out. They’ll come in a helicopter.” He kissed each of them on the forehead. “I love you. Stay right here.”

“We will.”

Brandon gazed down the gnarly cliff face. Before starting his descent, he didn’t look back. He didn’t want that mental picture, in case it was the last time he saw his kids alive.

Brandon managed to bushwhack a few kilometres down to the base of the mountain, suffering another bad fall on the way. Fortunately, he’d landed on his back in a dense bed of ferns.

Exhausted and bloodied, bare feet in shreds, he emerged from the forest and bumped into a family of hikers. They called 911.

“Your kids will be okay,” the father assured him. “Let’s say a prayer together.”

Around 4 p.m. that afternoon, at home in Coquitlam, Claire felt a weird sensation. Brandon had said they’d be home by nightfall. It was still hours away, but something didn’t feel right. She went to phone him but couldn’t find her cell, and then the babies needed attention.

Around 5 p.m. her phone rang. Relieved, she imagined it was Brandon, calling to say when they’d be back.

It was a dispatcher from Coquitlam Search and Rescue. “Mrs. Hoogstra? I’m sorry to tell you that your husband and children took a bit of a fall.”

“Oh my gosh. Are they hurt?”

“Your husband hit his head, but he said the children are alive. We’re going to pull them out with a helicopter. That’s all we know so far. I’ll keep you updated as I get more information.”

Around 8 p.m. the dispatcher called Claire again. “Your husband’s at Eagle Ridge Hospital,” he told her. “He hit his head, but appears to be okay.”

“Oh, thank goodness.”

“We are having trouble locating your children.”

“What?” Claire gripped the counter. “Aren’t they with him?”

“He made his way out, but he had to leave them behind.”

For a moment, she couldn’t speak.

“Ma’am? Are you still there?”

Claire focused on her breathing. “I’m here. I’m not going to pass out. But I can’t lose my children.”

An hour later, when two RCMP officers knocked at the door, her stomach dropped. Dear God. Her father had been in law enforcement. He said the worst part was informing a parent of their child’s death.

Mercifully, the officers only needed more information.

Around midnight, the RCMP brought Brandon home for fresh clothes. He’d been stitched up, given a tetanus shot and checked for internal injuries. Claire understood the fragile emotional state he’d be in.

“Honey,” he said, trying not to weep, “I’m sooo sorry about what I did to the kids…”

“No, you were just taking them on a hike,” she soothed. “They’re coming home, I promise. Now go and help find them.”

Al Hurley and Bill Papove, two veteran volunteers with Coquitlam Search and Rescue, had been dropped off by a helicopter part way up the mountain, just before darkness fell. Details were still scarce. They only knew two young children were stranded in Class 5 terrain—the most difficult.

The two men, wearing 18-kilogram emergency packs, spent all night zigzagging down the treacherous terrain. GPS recorded their route as they searched for signs indicating which of the drainages Brandon and the kids had been descending.

At 4:30 a.m. Hurley and Papove, in need of food and rest, met another SAR team on the mountain to hand off information. Then, the two men hiked down to base camp—a mobile home equipped with live satellite images and a topographical map. Brandon helped trace their route as best he could. When the teams set off again, he began to cry. Soon he was bawling in agony. As a parent, he knew he had one job: protect your children. God asks us to forgive others, but if you’re responsible for your children’s demise, how do you ever forgive yourself?

RCMP constable Morgan Nevison introduced himself. Though Nevison had not been specifically trained in emotional support, he had a gift for it. He’d served in the military, and Brandon’s dad had fought in Vietnam and developed PTSD. The two men were soon chatting like old friends.

“You know,” said Nevison, “a buddy, he got lost in these woods a few years back. He was missing for three days before they called it off. As they were preparing to leave, he knocked on that door right there.”

Just then, SAR volunteer Jim Mancell stopped in with good news: searchers had spotted a blue shoe.

Nevison, with his easy manner, kept Brandon engaged until Jim returned.

“We’ve got voice confirmation. I’ll keep you posted.”

Please God, let them be unharmed.

Finally, 20 minutes later, Jim came back inside: “Great news. We’re with your kids.”

Brandon leapt up, laughing and crying. When Nevison drove him to an open field, he was moved to see so many strangers in bright red SAR jackets.

Soon the thwack-thwack-thwack of rotors announced the arrival of the helicopter. Oliver was dangling from a long line, between Al Hurley and another volunteer. Brandon ran to embrace his son. Before long the helicopter returned with little Ezri on the line. The kids were rushed to Royal Columbian Hospital, in New Westminster, to check for injuries and hypothermia.

It turned out they were fine, just cold and hungry. After Brandon left the children had talked a bit. Just before dark they heard a helicopter. They were so exhausted they soon fell asleep, huddled together for warmth. The kids kept their word and didn’t move from their spot all night. “They had very little trauma afterwards,” Claire explained later. “They both felt that Brandon had been truthful about their rescue and it was just a matter of waiting for a helicopter.”

Of the hundreds of rescues he’s participated in, Al Hurley found this one among the most satisfying. “Many of us are parents,” he explained. “When you hear the words ‘injured,’ ‘child’ and ‘wilderness,’ it gets intense. This one had a happy ending. That’s not always the case.”

Two months after the rescue, in July 2019, the Hoogstras moved to Washington State, across the border from B.C. Oliver and Ezri still love hiking with their dad, though they prefer to stick to shorter routes now. They remember huddling together that cold night on Burke Mountain, of course, but otherwise the brother and sister seem untroubled.

Brandon is a different story. Having quit smoking while the family lived in Canada, he started up again to soothe his nerves. He paints. Flashbacks overwhelm him. In tears, he takes solitary walks in the forest.

Before the Hoogstras left Coquitlam, a volunteer dropped by to return their recovered items—a backpack, fishing gear, some shoes. One search manager called them “a trail of bread crumbs” that helped to lead the rescuers to the children.

In the backpack, someone had placed a bright red jacket with a patch that reads Ridge Meadows Search and Rescue. The jacket reminds the Hoogstras of everyone who risked their safety to help people they didn’t know. When Brandon is overcome by guilt, or anxiety, or sadness, he takes out the red jacket.

Putting it on helps him remember he’s not alone—there’s always someone out there who is willing to help.

Next, check out our collection of the most gripping survival stories.

Air it out

Whether you’ve purchased a used car that someone smoked in, or have finally kicked the bad habit yourself, you may be itching to learn how to get rid of that smoke smell in your car.

The first thing you need to do to get rid of the smoke smell is clean, clean, clean! Drive your car to a well-ventilated area. Roll down the windows, remove any belongings and take out every scrap of trash.

Vacuum all surfaces

Next, remove seat covers and floor mats and begin to vacuum every inch of your interior. A handheld vacuum, or vacuum with an attachment meant for getting into the deepest nooks and crannies is ideal for this job. Vacuum your seat covers (or launder them at home or at a self-service laundry if the tag says they’re washable) and floor mats separately, after they’ve aired out in the sun for a bit.

Wash all surfaces

Now, combine white vinegar and water in a 1:1 ratio in a spray bottle and spritz your upholstery. Use a microfibre cloth and wipe down all of the interior upholstery, interior side panels, steering wheel, dashboard, etc. (Check out more genius uses for vinegar all around the house.) You should also use a glass cleaner to remove any cigarette residue on your windows and windshield. (Here’s how to clean inside car windows like a pro.)

Ventilate

Next, start your engine, turn the fan on high and the air conditioner to the lowest temperature. With windows rolled down, allow the car’s air ventilation/filtration system to pull the smoke smell out of the car. With the fan and A/C still on, spray an odour neutralizer into the vents. Repeat this process, but this time, turn the heat all the way up and spray the neutralizer into the vents again.

More drastic measures

Despite your best efforts, sometimes the smell of smoke has permeated so deeply that it is nearly impossible to eliminate. In that case, consider taking more drastic measures, like replacing the upholstery, headliner (roof material) and carpets. (Here’s expert advice on how to install new car carpet.)

If your car smells of smoke from a bonfire instead of cigarettes, you can usually get rid of that smell by putting your car in a well-ventilated area with the windows down to let it air out. After a little while, sprinkle some baking soda on the carpet and floor mats and vacuum it off.

If you have no interest in doing this job yourself, hire a pro! It costs anywhere from $125 to $200 for a thorough interior cleaning, depending on your location and the size of your vehicle.

Next, check out these car interior cleaning tips.

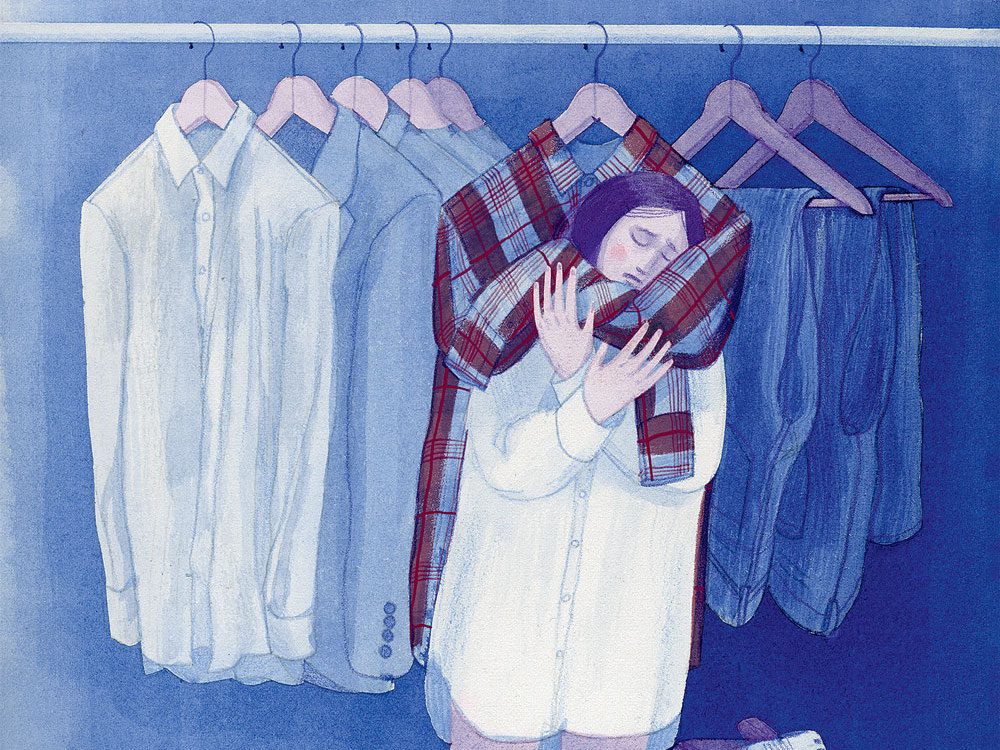

A new mourning

My daughter Hannah was deep in wedding preparations when her fiancé, Scott, was killed in a car crash in January 1998. She was a 25-year-old medical student and not much interested in history, so she knew almost nothing about how people in previous times had mourned. And yet, in the months after Scott’s death, without realizing it, she recreated many traditional mourning customs from around the world.

Like Queen Victoria or mourners in ancient Rome, she wore special clothes—something of Scott’s every day. She remembered him in company, taking an unintentional cue from bereaved Jews who say Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, together in synagogue every day for up to 11 months. “The Scott Coffee” met every Sunday at his favourite Vancouver spot to flip through a photo album of his and Hannah’s, sharing memories. Many cultures have long followed a mourning timeline, the period during which, for example, people donned black or limited their social lives. Hannah also did this, wearing her engagement ring on her left hand until the one-year anniversary of Scott’s proposal. After, she moved it to her right hand.

Our era has worked hard to minimize mourning, a shift that started in the aftermath of the First World War. Following the unthinkable losses of the war—and also, among other reasons, the belief that medical advances would relegate death to a concern only for the very old—many people began to see grieving traditions as old-fashioned, irrelevant and morbid. Very gradually, in the past few decades, the pendulum has begun to swing back as people realize mourning, and death, are too important to be sidelined.

Years later, when I asked Hannah about her wholehearted mourning, she told me about the sadness she experienced when her father and I divorced. She was nine when it happened, but she never cried about it and never wanted to talk about it. With Scott’s death, she wanted to let herself experience the fullness of her grief. “I wanted to do the work,” she said, “and have the worst part over.” Hannah found her way on the mourner’s path by instinct, but there are some traditional tips that would benefit many bereaved people.

Mourning requires some effort

Sigmund Freud wrote about “the work of mourning,” a bereaved person’s painful acceptance that their beloved is no longer alive. Freud believed the relationship could evolve into a continuing, internalized bond—one that allows the mourner to achieve a new normal. Such work is enormously flexible and individual and can range from actions like Hannah’s “Scott Coffee” to hours spent staring at a wall, remembering the dead and wishing for their return.

Rosa Spricer, a Toronto psychologist, says, “Research shows that people from cultures that allow them to fully grieve for a long period of time tend to have less complicated and unresolved grief.” But paying attention to your grief can be easier said than done, she adds, especially if your usual way to deal with difficult feelings is to ignore them.

Sarah Kennedy, a registered clinical counsellor in Vancouver, agrees that stifling grief can lead to long-term difficulties. Often, clients who’ve tried to repress their grief arrive in her office with anxiety, sleep problems, relationship difficulties and more. “An array of symptoms can come knocking, as if to say to the denier, ‘You’ve forgotten to take care of something important here,’” she says. While mourning can be frightening, she adds, speaking of her most resistant clients, “They know that grieving is the medicine they need.”

Choose the right support system

Bereavement can be a time of great loneliness, when friends and family are more important than ever. But the modern aversion to discussing death has left many of us inhibited and clumsy in these situations. People may inadvertently downplay the mourner’s plight or say the wrong things, like, “Are you still brooding about that?” or, “Life goes on. It’s time to forget the past.”

Unfortunately, during a fragile time, such false steps can feel like abandonment, says Spricer. These failures in friendship and family are common, she adds, but they don’t have to be. Some mourners benefit from directly stating what support feels best for them. Spricer recalls, for example, a church funeral at which attendees found instructions titled “Ten Things Never to Say to a Mourner” at every seat.

Kennedy’s clients often mention a “failure of attunement” from family and friends. When they experience others’ impatience with the speed of their mourning, she urges them not to internalize a sense of failure. “People need to be discerning about whom they open up to when feeling vulnerable and overwhelmed by their feelings,” says Kennedy. When looking for confidantes, head for good listeners, not those who jump in quickly to tell you what you should be doing.

Hannah also chafed at friends who didn’t respond as she hoped but now suggests trying to cut friends and family some slack. When you feel better, you will likely find their friendship is still worth having.

Remember you’re in charge

People who attend an Orthodox Jewish shiva, or condolence visit, don’t approach a mourner unless the mourner beckons them. The mourner’s instincts and wishes are paramount. That’s something to keep in mind whatever your religion (or lack of religion). “There isn’t one way to grieve,” Spricer says. “Every mourner comes to loss with their own history and their own ways of coping with emotion.”

In other words, mourning isn’t one-size-fits-all. Don’t let anyone tell you what to do, how you should feel, or how long it will be until you feel better. Even when two people are mourning the same loss—siblings, for example, who are mourning a shared parent—each person has to be able to choose their own path. This can be a source of friction or hurt to the other person, but it needs to be respected.

When it came to mourning, Hannah marched to her own drummer. More than 20 years after Scott died, she is a busy doctor, wife and mother, but for a long while she still wore his engagement ring on her right hand. To her, it was the sign of a well-earned, continuing bond that coexisted healthily with her current life.

According to the Canadian Cancer Society, around 26,900 Canadians will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2020. What’s particularly shocking is that colon and rectal cancers are striking younger adults more often than in the past. For example, millennials born in 1990 have more than twice the risk of developing colorectal cancer than their peers born in 1950. “Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers,” said Edward L. Giovanucci, MD, ScD, in a press release from the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR).

A 2017 report by the AICR and the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) yielded some good news: “There is a lot people can do to dramatically lower their risk.” The findings are “robust and clear,” Dr. Giovanucci says: “Diet and lifestyle have a major role in colorectal cancer.”

Specifically, the report suggests that eating whole grains daily may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by about 17 per cent. This adds to previous scientific evidence that fibre-containing foods may decrease the risk of this particular cancer. In the report, scientists conducted a comprehensive analysis of 99 existing scientific studies, including data on about 29 million people. Of those, over a quarter of a million had been diagnosed with colorectal cancer.

What exactly qualifies as whole grain?

Whole grains include both the grain’s bran and germ, says colorectal cancer expert Darrell Gray, MD, of The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, who was not directly involved in the study.

“The bran is the multi-layered outer skin of the edible kernel. It contains important antioxidants, B vitamins, and fibre. The germ is the part of the grain that has the potential to sprout into a new plant. It contains many B vitamins, some protein, minerals, and healthy fats. “The whole grain is a rich source of phytochemicals and antioxidants that have anticancer properties,” Dr. Gray explains.

He adds that “whole grains are thought to exert beneficial effects in colorectal cancer prevention by lowering fasting insulin levels.”

How much do you have to eat to see benefits?

According to the study, three servings of whole grains per day (a total of 90 grams) was associated with the 17 per cent decrease in cancer risk. A single serving of whole grains is equal to a 1/2 cup of cooked brown rice, oatmeal, or other whole grain, or a cup of whole-grain cereal. (Check out more surprising health benefits of oatmeal.)

Dr. Gray suggests bran-flake cereal, but there are many other options. For foods that contain not only whole grain but also other ingredients (for example, whole grain crackers, granola bars, bread and muffins), you’ll have to eat a larger amount to get the optimal dose of whole grain.

The report notes that some lifestyle habits are associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer:

- Eating lots of red meat such as beef or pork (more than 500 grams, or a little over 1 pound, cooked, per week)

- Eating hot dogs, bacon and other processed meats on a regular basis

- Being overweight or obese

- Consuming two or more daily alcoholic drinks (30 grams of alcohol) daily, such as wine or beer

- Smoking

Other ways to lower your risk of colorectal cancer

In addition, the report states that people who are more physically active (at least 30 minutes of physical activity per day) have a lower risk of colon (but not rectal) cancer compared to those who do very little physical activity. It also found limited evidence that eating fish and foods containing vitamin C (such as oranges, strawberries and spinach) is associated with lower the risk of colorectal cancer.

“All of this points to the power of a plant-based diet,” says Alice Bender, RDN, director of Nutrition Programs at AICR.”Replacing some of your refined grains with whole grains and eating mostly plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables and beans, will give you a diet packed with cancer-protective compounds and help you manage your weight, which is so important to lowering risk.”

“When it comes to cancer there are no guarantees,” she adds, “but it’s clear now that there are choices you can make and steps you can take to lower your risk of colorectal and other cancers.”

Next, find out 30 painless ways to increase dietary fibre.

While I pride myself on being from the small town of Cochrane, Ontario, the reality is I’ve spent the majority of my life as a city boy in Ottawa. That being said, my fondest memories as a boy are the days my gramps took me out fishing on the beautiful and abundant lakes of northern Ontario.

In all those years that he took me out fishing on his hard-earned weekends, we never caught a fish. We did however sing songs, test out how fast his 5-hp outboard motor could go and practice our stone-skipping skills with rocks I stored in my pockets. I have no idea why we never caught anything—Gramps always claimed we had his bad luck to blame.

The best memories of those trips were the endless questions I had for him and his ability to satisfy them. During this time together, I not only learned the art of fishing but also what his life was like when he was young, the games he played with his siblings and how they sat around the radio. I also learned how much he regretted missing out on doing things with his own kids because he was working.

Sadly, my gramps passed away in April 2014, but my son, William, who was born in May 2014, is named after him.

One summer morning in 2015, I sat out on a dock on Lake Dalhousie, an hour outside of Ottawa, with my then-three-year-old daughter Brynn. We were sharing a tiny push-button Dora the Explorer fishing rod (William wasn’t old enough to go fishing yet). One a normal day, the only thing that could make Brynn sit still for a minute was a television or the straps of her car seat. But this day was different. We sat out there with our legs dangling over the water for a long time. We sang songs, threw rocks and took turns casting and reeling as I answered a million questions. In lieu of a hook, Brynn’s fishing rod had a plastic star tied to the end of the line—we caught nothing but memories.

Thanks, Gramps. I look forward to many years of my own “bad luck.”

Next, read one woman’s touching tribute to her late grandmother.

Meeting Romeo

Like most middle-aged women dipping a toe back into the dating scene, Jodi got on Tinder because a friend convinced her to. They were hanging out, drinking wine. It was a few weeks into 2018, and Jodi, a health information analyst in West Kelowna, B.C., hadn’t been on a date in more than 23 years. Her profile mentioned her love of camping and kayaking and included a link to her favourite country song, “Meant to Be.”

One of the first guys she met was Andy. She was sitting in her home office when she got a message from him: “I like your profile.” Turns out they had the same favourite song, which felt promising. They met at Starbucks that afternoon, and Andy told her he was moving back home to Canada after having spent the last decade in Vietnam. He was an engineer on offshore oil rigs and had apparently done well for himself. Now he wanted to slow down and enjoy life with someone who wanted the same things. He told her his name was actually Marcel Andre Vautour. Jodi started calling him Dre.

On their third date, sitting together in her living room, Dre told Jodi he was falling for her. Big time. “Everything he said was exactly what I wanted to hear,” says Jodi (who asked us not to print her last name).

They started to plan their life together. Dre would have to go back to Vietnam to get his money, much of which, he explained, was in gold bars. They would go together, he said—sort of like a honeymoon. First, though, he was going to take a job delivering water to oil rigs in Edmonton. It would just be a few weeks, and the money was great, he told Jodi. Then he asked if he could borrow $500, so he could pay for the recertification required to take the job. Jodi wasn’t totally comfortable with the idea, but Dre had a story about how he couldn’t access his own funds and promised to pay her back. And at the time, she believed him.

Like other fraudsters, phony Romeos are thriving in the digital era, when you don’t even have to meet your mark in person—or live on the same continent—to take them for all they’re worth. According to the most recent numbers from the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC), romance fraud cost Canadians $19 million in 2019. That’s more than any other form of fraud in terms of monetary losses. It’s also an extremely low estimate: The CAFC and the FBI believe that only between five and 15 per cent of fraud victims contact the authorities, meaning the actual damage is far greater, from both a financial and psychological perspective.

Under the right circumstances, almost anyone can fall prey to romance fraud, but the most common victims are well-educated women in their late 40s, 50s and 60s. (The FBI estimates that 82 per cent of victims are female, but that number may be off since it’s possible men are even less likely to report.) They tend to be trustworthy, prone to impulsivity, community-minded and, yes, romantic.

To a con man, your Facebook page provides an invaluable cheat sheet: a years-long record of your interests, values and personality, including the organizations you care about, the politics you subscribe to, your hobbies and favourite TV shows. So suddenly you’re not just meeting some guy—you’re meeting a fellow outdoor enthusiast who also loves dogs or basket weaving or your favourite song.

Shortly before Jodi was expecting Dre back from Edmonton, he called to say he was in trouble over unpaid back taxes. He had a big cheque to cash from the Edmonton job—a little more than $49,000—but if he put it in his account, the government would claim it. Without the money, he couldn’t pay his subcontractors. They wouldn’t be able to go on their trip. There was one possible solution, he said—not immediately, and almost like it had just occurred to him. Maybe he could have his employer make the cheque out to Jodi, and they could deposit it into her account instead. Jodi questioned whether this was legal; Dre’s answer was that pretty soon their names would be on the same cheques anyway. Wasn’t that what she wanted, too?

They were on FaceTime when Dre e-deposited the cheque into Jodi’s business account and got her to transfer him $19,500. To this day, she doesn’t understand why her bank didn’t put a hold on such a large deposit.

It was the Easter long weekend, and that same afternoon, Jodi flew to Vegas for a wedding. She told everyone about her new boyfriend. “People said I was glowing,” she recalls. After she got home, she drove to the grocery store. Dre would be back in a few hours, and she wanted to have dinner ready. At the checkout, her debit card was declined. A second card didn’t work either. Her stomach started to sink. When she got home, she sat down at the computer and brought up her banking information, which confirmed that Dre’s cheque had bounced, leaving her nearly $20,000 in overdraft. Between that and the money she had lent him for work expenses and accommodations, she was out $45,000. Her dream man was a con man. And he was gone.

Criminal history

Police records on Marcel Andre Vautour go back at least 24 years. While romance scams appear to be his specialty, other allegations and charges against him include credit card fraud, identity theft, possession of goods obtained by crime over $5,000, obtaining by false pretense and auto theft. He has mostly escaped prosecution, but in 2005 he did receive a suspended sentence of one year’s probation in Quebec for credit card fraud. In 2009, he served a six-month conditional sentence in Victoria, followed by two and a half years of probation, for fraud. There are active arrest warrants for him in Quebec and Manitoba. The fact that romance fraud is almost never handled federally plays a key role in how scammers are able to evade capture by skipping from one jurisdiction to another.

Soon after being conned, Jodi was approached by a 46-year-old B.C. nurse named Rosey, who had also fallen for Vautour’s stories while going through a difficult patch with her husband. Rosey ended up giving Vautour just under $7,000 before he disappeared on her—but she discovered a Facebook page he’d created while he was with Jodi. Talking on the phone, the two women discovered that Vautour had told them the same tall tales about gold bars and fancy homes, and both had seen the same photo of the bed covered in American cash. Investigating Vautour soon became their shared passion project. They would check in every few days, giving each other assignments: Jodi traced the phony cheque that he had deposited into her account. Rosey spoke with members of Vautour’s family in Quebec and New Brunswick. They learned a lot about their scammer but nothing about his whereabouts. “We had almost given up,” says Rosey. “And then we heard from Andréa.”

Andréa Speranza, a 50-year-old divorcee and fire captain, met Vautour at a Tim Hortons in Halifax three months after he had scammed Jodi and Rosey. He was using the name March Hebert. On their first date, Vautour casually mentioned that his Crohn’s disease sometimes held him back from physical activity. About four months later, when Vautour said he had a medical emergency relating to his Crohn’s, she lent him $1,500, then $500 more when it turned out the medication he needed was more expensive than he thought, then another $2,000 for a second dose. He couldn’t access his own money, he said, because his backpack had been stolen. Looking back, she sees how the stolen backpack and the unproven medical claims were warning signs, but in the moment her brain just didn’t go there. “What seems crazier, the idea that he had his backpack stolen or that every single thing he ever told me was a lie?”

Their relationship lasted just over five months. During this time, Andréa gave Vautour about $5,000, most of it for medication. The last time she saw him, he was going to Toronto to pick up his dog from his ex. (Andréa paid for his train and accommodations.) From Toronto, he emailed her a link to the hotel he wanted to stay at; it came from an email address under a name Andréa didn’t recognize: March Vautour. Unsure of what this might mean, she started typing variations of Vautour’s name into Facebook, ultimately landing on a picture of her boyfriend with a single word written across it: BEWARE!

To catch a scammer

If the scammer has used a real name (or has a lot of online aliases), a private investigator can run a background check and hopefully find a criminal record and track them to an address—perhaps even locate assets. Then their victims can serve them with a small claims charge. This may or may not cover the full extent of the loss—in Ontario, for example, small claims max out at $35,000—but it’s often the best of the three available options, the other two being civil or criminal charges. Victims of romance fraud can (and should) make a complaint with the police, but actual criminal charges are rare. Numerous victims and experts I spoke with say that just getting the authorities to take a complaint seriously can be a challenge.

When Rosey went to the police, she was told that yes, Marcel Andre Vautour was a fraudster with a lengthy record of complaints. But since she had sent him the money while they were dating, proving criminal activity would be difficult. It was Andréa’s idea to take their manhunt public. In March 2019, she launched “Stop the March Madness Campaign,” an online publicity blitz with three objectives: to raise awareness about the prominence of romance fraud, to provide support and community to victims and, of course, to catch the dirtbag who did this to them.

They got a few tips from women who had been out with Vautour in Toronto, but nothing particularly useful—until they heard from Nikola. The 28-year-old backpacker was visiting Toronto from the Czech Republic on a 12-month work visa and first met “Marc” at a hostel in North York in March 2019. Nikola and Vautour were never a couple; instead he said he could get her a well-paying job working as his assistant. When she mentioned her plan to drive to B.C., Vautour showed her a photo of his beach house in White Rock that he had been meaning to get back to and offered to come along for the ride. After giving her a (fake) contract, he suggested Nikola get a Canadian credit card and went along to the bank posing as her new employer. Over the next three weeks, Vautour racked up $5,000 in charges on Nikola’s card and stole another $500 by depositing an empty envelope into her bank account.

Soon after they arrived in B.C. together, Vautour had to leave; an emergency, he said. By the time Nikola realized what had happened, she was alone and broke.

Nikola gave Vautour’s other victims a good tip: Vautour had bought himself a fancy backpack with her credit card, and knowing him, he would try to sell it. Rosey went onto Kijiji, and there was the identical backpack, for sale by a guy in Nanaimo named Marc.

This was June 2019. Jodi immediately left for Nanaimo with her new boyfriend, Vince. Rosey was also en route. They started visiting the kinds of places where he’d typically hang out. At Tim Hortons, a worker said Vautour had been in just a few hours ago. At a library, they showed a flyer of Vautour to a guy, who responded, “Oh yeah, sure. That’s Marc.” He was living just a few blocks away at the Salvation Army.

At this point, Jodi had spent more than a year fantasizing about coming face to face with the guy who nearly ruined her life. “I wasn’t looking for an apology or anything. I just wanted him to see that he hadn’t broken me,” she says. Just as she and Vince walked through the door at the Salvation Army, she spotted Vautour walking out in the other direction. “Hey, Dre,” she said, cornering him in the reception area. At first, it seemed like he was trying to place her. And then he looked scared. He claimed he had been messed up on drugs when they were together and he barely remembered anything. He was finally getting clean and would pay her back, he said, before getting buzzed into a secure area of the shelter. Jodi called 911.

By the time police got there, Vautour had vanished.

That day was the last time Jodi, Rosey, Andréa or Nikola have seen Vautour. They are still in touch with each other and with a community of people (16 in total, so far) who allege that Vautour defrauded them.

Andréa has taken a self-defence course and installed a new security system at her home. Rosey is living apart from her estranged husband. Nikola has returned to the Czech Republic. Jodi has been with Vince for nearly two years now. That day in Nanaimo, when she saw Vautour, her heart was pumping pure ice. But sometimes she’ll come across a photo of the two of them, and she’ll feel a sudden rush of affection. “It’s only for a second. I have to knock myself in the head and remind myself of who he really is.” That part is worse than losing the money, although not as bad as the shame.

Yes, romance scammers are master manipulators who target, groom and exploit innocent victims. But our culture has its own role to play. “Invisible woman syndrome” describes the phenomenon wherein women are ignored after they reach a certain age—by potential employers, by suitors, by bartenders. No longer imbued with youth or fertility, we have ceased to serve our biological purpose and are deemed less valuable. Then along comes a person who sees you and appreciates you and promises to make all of your dreams come true. Who wouldn’t want to believe in that?

Next, read the true story of how an elderly woman was defrauded of her life savings.

© 2020, Courtney Shea. From “He Stole Their Hearts, Then Their Money. Meet the Women Trying to Catch One of Canada’s Most Prolific Romance Scammers,” Châtelaine (January/February 2020). Chatelaine.com.

The fall

Xavier Cunningham was having fun that warm Saturday afternoon in September 2018 with his buddies Silas and Gavon. Xavier, a bubbly, energetic 10-year-old, enjoyed playing in the yard behind his house in Harrisonville, Missouri.

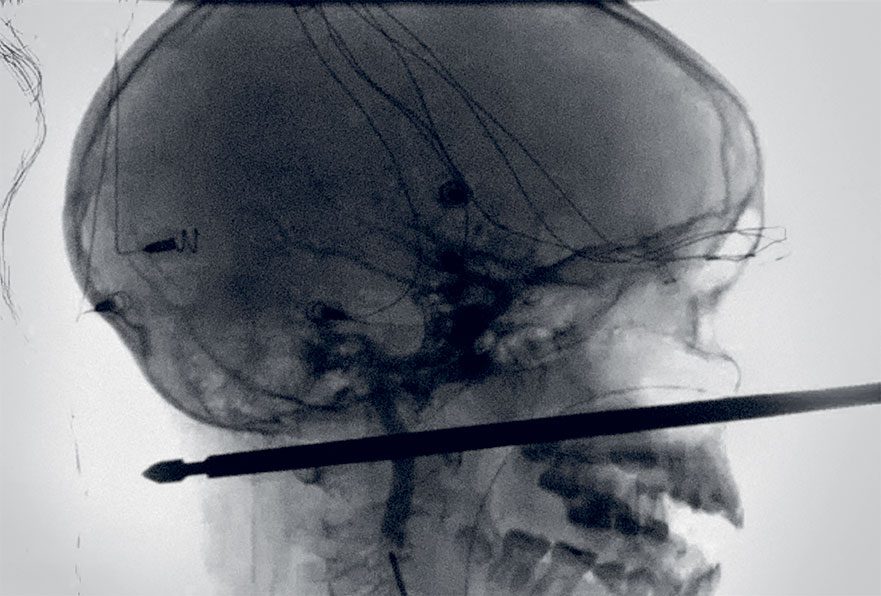

That day, the trio was chucking around a stainless-steel skewer, throwing it into the ground like a spear. At 43 centimetres long and more than half a centimetre thick, the square-edged skewer was used to rotisserie meat; one end had four sharp prongs attached.

Eventually, they ditched the skewer near a neighbour’s tree house, sticking it in the ground with the four prongs anchoring it. With the neighbour’s permission, they climbed the three-metre ladder. Up top, a few yellow-jacket wasps buzzed around. “If we don’t bother them, they won’t bother us,” said Xavier.

But the boys hadn’t seen the large wasp nest wrapped around part of the tree house. Soon the insects were coming at the panicked boys thick and fast, in a dense black cloud. “I’ll get my mom!” Xavier yelled, but now he stared, frightened, at the tree-house ladder, which was covered in a seething mass of angry wasps. This is going to hurt, he thought. His hands crunched on the insects and the stings were painful as he grasped each rung, going as carefully and quickly as he could.

When he was about halfway down, a wasp painfully stung the thin skin of a knuckle on his left hand. As he swatted at it with his right, he lost his balance and fell, face down. Just before breaking his fall with his arms, he felt a sting just under his left eye. Was that a wasp? he thought. Then he realized he’d landed on the metal skewer. Nearly half of it was buried in his head. Screaming, he got up and ran toward home.

Gabrielle Miller, Xavier’s 39-year-old mom, was upstairs folding laundry in the two-storey brick home she shared with her husband, Shannon, a high school teacher, and their four children. Shannon had taken two of their kids on a day trip to nearby Peculiar, while Gabrielle, who manages a local title-insurance business, stayed at home with Xavier and his 14-year-old sister, Chayah. She heard her son screaming and sighed. When will he grow out of this stuff?

Xavier usually made a fuss over the smallest scratch. If one of their two dogs jumped up on him, he’d start screaming; he was too scared to walk Max, the coonhound he’d gotten as a puppy, because the dog pulled on the leash. His overreactions were pretty much a daily occurrence.

Gabrielle was almost down the stairs, Chayah right behind her, when Xavier pushed the front door open, shrieking, “Mom, Mom!” Gabrielle was trying to make sense of what she was seeing. “Get them off!” Xavier was yelling, batting at wasps. She pulled wasps off him, getting stung herself.

Gabrielle was confused and shocked. “Who shot you?!” It looked like there was an arrow through her son’s face; a single trickle of blood ran down from it. With his stung, swollen hands, he touched the tip of the skewer on the back of his neck, a lump that hadn’t pierced the skin.

Gabrielle guided Xavier out the front door and into the front of her Camaro. She then ran to the driver’s side. A shocked neighbour, watching as the car backed out into the road, thought, That boy’s not coming home.

Hospital

Gabrielle rushed into the Cass Regional Medical Center emergency room with a remarkably calm Xavier walking alongside her, the huge spike sticking more than 20 centimetres out of his face. The skewer didn’t appear to have hit his spine, but an X-ray can’t show tissue damage. ER staff realized they’d have to send him somewhere with more advanced imaging equipment: Children’s Mercy Hospital in downtown Kansas City, 40 minutes north.

To prevent Xavier from moving his head, staff fitted a plastic cervical collar around his neck and wrapped his entire head in white gauze to help stabilize the skewer. The only thing left exposed besides it and its four sharp prongs—caked with mud from where they’d been stuck in the ground—was his mouth.

Dr. Jeong Hyun, the pediatric surgeon working the emergency room at Children’s Mercy that afternoon, couldn’t believe his eyes when Xavier was rolled in at about 4 p.m. He asked Xavier to wiggle his toes and fingers. He was relieved that Xavier was so responsive; it meant that neither his spine nor brain had likely been hit.

The skewer also hadn’t punctured any of Xavier’s vital blood vessels. If an artery such as the carotid or the vertebral, which carry blood to the brain, had been hit and was leaking out internally, it could cause a stroke. Dr. Hyun was amazed to see via a CT angiogram that nothing was leaking and the skewer had narrowly missed every vital artery. They looked to be millimetres, if that, away. That’s spectacular, thought Dr. Hyun. But now what?

If the skewer had any kind of bend, a sharp edge or a gap, then pulling it out would be rolling the dice, as it could catch on an artery and rip it open. But the only way to get a clear picture of the skewer was with biplane angiography—a piece of equipment that gives doctors a three-dimensional view inside the vascular system. Children’s Mercy did not have it, since vascular problems are so rare in kids. But the University of Kansas Medical Center, less than five kilometres away, did. Xavier would need to be transported to a third hospital.

It was now 7:30 p.m. Xavier had been impaled for six hours.

Preparing for surgery

Dr. Koji Ebersole, an endovascular neurosurgeon at the University of Kansas Medical Center, stared at a photo of Xavier on a gurney. He had also never seen anything like the boy’s injury. How deep is that thing? he wondered. And how is this kid even alive?

Dr. Ebersole had to get Xavier into the angiography suite as soon as possible —but first he needed a plan. He was the best-trained neurosurgeon for more than 200 kilometres, but there was nothing in the medical textbooks that could help with this one. He needed to make some phone calls.

Meanwhile, his colleague at KU Hospital, Dr. Kiran Kakarala, an otolaryngologist (or ENT—ear, nose and throat specialist), was at home with his family when he received Xavier’s X-rays. His first thought was that the odds were against the boy. How can someone live through an impalement like that? he thought.

Yet he was alive—which told Dr. Kakarala they had a chance of removing it. But how? If they hit any key blood vessels, Xavier could experience a debilitating stroke, or he could die.

For the next couple of hours, Drs. Ebersole and Kakarala consulted with various specialists. They knew they needed to see exactly what the skewer had damaged, or still could damage, and then remove it while carefully monitoring its exit. Using the angiography suite required a team of 15 to 20 medical staff. It would be tough to get the right people together so late on a Saturday evening. Plus they’d have a better chance of saving the boy if they were well rested.

But could Xavier wait until morning? Was he stable mentally? Dr. Ebersole asked the doctors in pediatric ICU, where Xavier and his family waited, to gauge whether he was brave enough to hold on; everything depended on his state of mind and his ability to refrain from grabbing the skewer. When Dr. Ebersole heard back from the hospital at about 11:30, he made his final call of the evening. “We can wait until morning,” he told a relieved Dr. Kakarala. “The boy is on board.”

It took both doctors longer than usual to get to sleep; each tossed and turned as they ran through various scenarios. It could go either way.

“The biggest problem is that barbed end,” Dr. Ebersole told the team assembled at 8:30 a.m. in the angiography suite. He pointed to a computer screen; the image on it was an X-ray, which showed the skewer had a notch in the shaft near the point. If they pulled the skewer out the way it went in, the notched tip could rip an artery open, but it was also their safest option.

One floor below, Dr. Kakarala was with the anaesthetists, inserting a breathing tube into Xavier so he could be anaesthetized. The skewer had gone through his jaw muscles, and Xavier couldn’t open his mouth widely enough to fit a tube, so the doctors would thread it through his nasal passage and down his throat. This is painful for adults and worse for a child. “I’m sorry, but this is going to hurt,” Dr. Kakarala explained gently.

They numbed his nasal passages and started the procedure. Xavier didn’t complain, even when they struggled to get it around the sharp corner at the top of the nasal passage. It took about 40 minutes. Finally, Xavier could be put under—and they’d get a look inside his head.

One lucky kid

In the angiography suite, about 20 surgeons, specialists and nurses waited. The boy was transferred to the operating table and about a dozen little wires with fine needles were pierced into Xavier’s scalp; they would continuously monitor the brain’s electrical activity. If there was any decrease, the technologist stationed in the corner of the room would alert the surgeons.

Two mechanical arms, one attached to the floor and the other to the ceiling, were positioned close to Xavier’s head. Each arm held two X-ray devices that moved in wide arcs around his head to create 3-D images that appeared in real time on a large flat-panel display.

Drs. Ebersole and Kakarala could now see the one-in-a-million trajectory the skewer had taken: it had missed Xavier’s spine by less than two centimetres. It had missed the cerebellum, located at the bottom of the brain, which controls functions like balance and speech—also by less than two centimetres. It had punctured the carotid sheath, which contained his hypoglossal and vagus nerves, which control tongue function, swallow reflex and the voice box, but didn’t appear to have damaged them.

The skewer had torn the jugular, but it appeared to have occluded, or sealed itself, against the skewer. Most importantly, it missed both the carotid and vertebral arteries. In fact, it appeared to have nudged them out of the way—without puncturing them. I don’t know how a kid can be so lucky, thought Dr. Ebersole.

It’s time

The team was as ready as they’d ever be. Now they had a view of things from inside and outside. Though nobody had discussed up to that point who was actually going to attempt to pull out the skewer—there was no rule book for this situation—Dr. Jeremy Peterson, a 32-year-old chief resident, thought it might fall to him, as he was training under Dr. Ebersole.

To get a feel for the skewer, Dr. Peterson placed his left hand at its base as an anchor, while his right hand grasped just above his left hand. He nudged it back and forth ever so slightly while Dr. Ebersole watched on the screen in case the movement harmed a vessel; the skewer barely moved. “It feels pretty solid,” Dr. Peterson said.

“Okay, let’s go,” said Dr. Ebersole. He’d be the eyes, watching the monitor, while Dr. Peterson would work on getting it out. He’d have to do it slowly and smoothly while being careful that his left hand didn’t exert too much pressure because it was literally on Xavier’s eye.

Dr. Kakarala had one hand on Xavier’s face to help steady his head. Dr. Peterson squeezed with his right hand while simultaneously pulling up with the same hand. The skewer was surprisingly hard to budge. It took all the strength in Dr. Peterson’s right arm. Then it did move about a couple of centimetres—and stopped. “It feels stuck on something,” said Dr. Peterson.

The screens showed that it was now so close to the vertebral artery that it was bending it.

They tried a new angle to move the skewer away from the artery. Looks like it’ll clear that now, Dr. Ebersole thought. “Okay, go again,” he told Dr. Peterson. It worked. Dr. Ebersole watched the tip of the skewer safely pass the vertebral artery.

“It’s sliding pretty easy now,” said Dr. Peterson. Yet he continued to pull it very slowly, especially as it passed the jugular.

Then, finally, the last hurdle: the carotid artery. The rod passed it smoothly, too—and suddenly, it was out. Dr. Peterson quickly put his finger in the hole, in case blood started gushing out. It didn’t.

Success

A cheer went up from many in the room—but not from Drs. Kakarala, Ebersole or Peterson. They wouldn’t relax until Xavier was conscious and they could know he was definitely unscathed. While it appeared the boy was out of danger, it was now a matter of waiting and seeing how he recovered.

It was 3 p.m. when Dr. Ebersole entered the waiting room and told Xavier’s parents simply: “It’s out. He’s okay.” It was the happiest moment of Gabrielle’s and Shannon’s lives.

“Can I hug you?” Gabrielle asked Dr. Ebersole, and she did.

When Xavier came out of the anaesthesia a short time later, a Spider-Man Band-Aid covering the wound on his face and with stitches along his neck, he asked, “Is it out?” Yes, it’s out, his parents told him. His eyes filled with tears as he looked out the window. “That sunshine, it’s so beautiful,” he said.

Two months after the accident, the only evidence of the skewer was a tiny bump beside Xavier’s nose and some numbness on the left side of his face—miraculously, he had no other permanent damage. His healing had been smooth and uneventful. For a while, his doctor recommended he see a therapist, primarily in case of PTSD.

Aside for a new fear of wasps, Xavier has coped remarkably well. These days, he often grabs the leash to take Max out—he’s no longer scared to walk the dog alone. And when he gets a scrape, instead of going straight to 10 on the pain scale, like he used to, he’ll calmly say, “This hurts pretty bad.”

“Is it skewer bad?” Gabrielle will ask, and Xavier will laugh—crisis over.

He’s still friends with Gavon and Silas, who were rescued from the wasps by members of the fire department who aimed hoses at the swarm. Gavon ended up with 150 stings, while Silas had just one, on his arm—and that entire arm swelled from an allergy he hadn’t known about. He, too, was lucky to be alive.

Next: A snakebite turned this woman’s Thailand vacation into a fight for her life

Experts talk about how important hydration is for health and weight loss. They also talk a lot about how to cut down on calories in things like your daily coffee. Now, new research shows that one cup of plain coffee could stimulate “brown fat”—and it might be another breakthrough for weight loss research.

What is brown fat?

Scientists from the University of Nottingham tested nine healthy male and female volunteers to see if caffeine stimulates “brown fat.” These fat cells are different from white, or regular body fat cells, because the body uses this fat to generate heat, according to Jaime Harper, MD, an obesity medicine physician who was not a part of this study. Meanwhile, regular body fat cells store energy, says Dr. Harper. And according to Jamie Kane, MD, the director of the Northwell Health Center for Weight Management, people also call this tissue “baby fat.” Since it generates heat, it also burns calories, as opposed to other types of fat which might contribute to inflammation, insulin resistance, and further weight gain, says Dr. Kane, who was also not part of this study.

What did the researchers find?

Researchers involved in the study tested to see if the caffeine in coffee stimulates these brown fat cells in humans. So the team determined the brown fat reserves of each volunteer and how much heat they produce using thermal imaging. They scanned participants before and after drinking either a cup of coffee, with about 65mg of caffeine, or plain water to see the impact.

The results show that drinking a single, standard cup of coffee may stimulate brown fat, which would increase the body’s metabolic rate—meaning that making these fat cells work hard with the help of coffee burns more calories. This research is a great start in looking at how what we eat and drink impacts how the body functions and uses energy, Dr. Harper says.

The study did not, however, show that patients lost weight from drinking caffeine. “While brown fat has a promising future in weight loss, the adult human has so little brown fat that it hasn’t been proven to play a role in overall body metabolism,” says Dr. Harper. There are some other study limitations, too, according to Dr. Kane. They only used a small sample size of patients that all have normal weights.

What does this mean for the future?

The next step for researchers is determining how to get the body to make more brown fat and boost metabolism. Researchers are hopeful that the body stimulates more brown fat, so that it could potentially aid in weight loss, according to Nesochi Okeke-Igbokwe, MD, a health expert not involved in the study. Still, until more research is done, keep on drinking your plain cup of Joe for the taste or the caffeine. Just make sure you’re not cancelling out any coffee health benefits, potential or otherwise, with extra sugars or fat, says Dr. Kane.

Here’s exactly how much coffee you can drink daily before it gets dangerous.

Prince Harry on Princess Diana’s Death

Princess Diana’s tragic death on Aug. 31, 1997 stunned the world—but few were affected like her youngest son, Prince Harry. Two decades after her fatal accident, he opened up about the mental health issues he struggled with as he came to terms with the loss of his mother.

Prince Harry was just 12 when his mother died in a car crash. During the painful years that followed, he stifled his emotions, forcing himself not to think about her as a teenager and into his 20s, he revealed in a candid interview with The Telegraph‘s podcast Mad World. When he finally allowed the grief to finally come to surface, he admits that he came “very close to a complete breakdown on numerous occasions.”

At 28, Prince Harry’s life felt like “total chaos,” he says. “I just couldn’t put my finger on it. I just didn’t know what was wrong with me.” So in 2014, he finally listened to Prince William’s pleas for him to seek help.

He started by taking up boxing to let out his frustrations. “Everyone was saying boxing is good for you and it’s a really good way of letting out aggression,” he says. “And that really saved me because I was on the verge of punching someone, so being able to punch someone who had pads was certainly easier.”

To be clear, Prince Harry stresses his mental health issues stemmed from his mother’s death, not his time serving in Afghanistan. However, working with a personnel recovery unit in 2015 actually helped him work through his own struggles. As he listened to stories of wounded or sick soldiers’ serious mental health problems, he began to understand his own issues better.

Eventually, he learned to follow their lead and talk about his emotions instead of just beating them out boxing. Coming clean to counsellors and loved ones, he finally addressed those stifled feelings. “[I] started to have a few conversations and actually all of a sudden, all of this grief that I have never processed started to come to the forefront,” Prince Harry says, “and I was like, there is actually a lot of stuff here that I need to deal with.”

Once he started opening up, he realized just how common mental health issues are. In fact, he spearheaded the Heads Together campaign with his brother and sister-in-law, Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, to empower people to discuss mental health. “Once you start talking about it, you realize that you’re part of quite a big club…and everybody’s gagging to talk about it,” he says. “I can’t encourage people enough to just have that conversation, because you will be surprised firstly, how much support you get and secondly, how many people literally are longing for you to come out.”

Here’s why William and Harry’s final phone call with Princess Diana still haunts them.

Ask an expert: How will kids going back to school during the pandemic change things for us once again?

Reader’s Digest Canada: Now that schools are reopening across Canada, will grandparents ever be able to see their grandkids again?

Infectious disease specialist Dr. Isaac Bogoch: Yes, they will. First of all, a vaccine is coming. I don’t know when it will arrive or when we will have the deployment of a vaccine in Canada, but when that happens, and it’s been demonstrated to protect against COVID-19, we’ll be able to shift towards normalcy. There’ll be less concern for people who have grandchildren in school.

Until then, people have to be very careful. We know now that people who are over the age of 60 who get this infection are more likely to have a severe course of illness. And as kids go back to school, it’s important that grandparents make decisions about whether or not they want to get very close to their grandchildren, or hug and kiss them.

Isn’t it just something you shouldn’t do?

Every person will make this decision based on their own unique circumstances. Some people might be living in a part of the country where there’s no COVID-19, or very few cases, and say, “You know what? The risk is extraordinarily small. I’m not going to change my behaviour just yet, but I’m going to watch this because it might change over time.” That’s completely acceptable. Other people’s circumstances might be higher risk, or they might just have a different perception of their risk, and say, “You know what? My grandkids are going back to school and I’m a little nervous about this so I’m going to practice physical distancing with them.” That’s also okay. As long as people are making informed decisions and thinking about it beforehand, then they’re doing something right. There’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all approach to this.

What do we know about how sick kids can get from COVID-19, or whether they’re carriers of the disease?

Children tend to not get as sick with this infection, but it doesn’t mean it can’t happen. In general, most children will have a mild course of the illness—but there will still be the rare event where a child will have a more severe illness.

That said, anyone of any age can get this infection. It doesn’t matter if someone’s a newborn, a hundred years old or anywhere in between. Also, anyone can transmit this infection. What’s still under debate is how efficiently younger individuals transmit it.

Why is that still not known for sure?

A lot of the earlier research was focused on people with severe infection, which tended to be older adults. Kids were just not coming to get medical care because they just weren’t getting that severely ill. Now there’s been a number of different studies on kids who’ve had this infection. Some have shown that children might not be transmitting the virus as easily or as effectively as other age groups. But others show that they can have high levels of virus in their system and are capable of transmitting the infection at the same rate as adults. Personally, I think it’s irrelevant. We should assume that anyone who’s infected can transmit this virus until proven otherwise and take precautions to avoid that from happening.

That’s difficult to do in schools. Do you think the re-opening is going to result in a surge of cases across the country?

I really don’t know. If you look at the provincial plans, they are all integrating fundamental public health principles into the school setting—including some degree of mask wearing in indoor environments, physical distancing, hand sanitation, cleaning of high contact surfaces and retrofitting classrooms for better air circulation. Of course, one of the key things will be how well these are integrated and we know some places are going to adopt these better than others. I don’t think it would come as a surprise to anyone if there was a case of COVID-19 introduced into a school at some point in the fall or winter. And there might even be transmission of this infection in the school. But I just don’t know to what extent that’s going to happen.

You named some of the measures meant to limit spread in schools. What about outdoor classrooms—is that being considered enough?

I do know that some schools are considering that and, while weather permits it, I think it’s a really good approach. From an infectious disease standpoint, being outside is an effective way of preventing the spread of this virus, since transmission of the virus happens overwhelmingly in indoor spaces.

Some re-openings in the United States have gone badly, which is worrisome. Do you think we’re being too impatient in rushing kids back to school?

No, I don’t. School provides so much more than just the education of kids. There’s also tremendous social and psychological development that happen for them there. There’s food security for some kids. If parents have to go to work, they can’t do that if their kids are out of school. There’s so many reasons why school is extremely important.

Of course, we do have to balance that with public safety. You can’t send kids back to school if they’re going to start amplifying COVID-19 at the school, in the home and in their communities. In Canada, sometimes we compare ourselves to the United States and it’s true we’ve seen some high profile outbreaks at schools there. It’s not to say that can’t happen in Canada—it certainly can—but in general, our infection rates are way smaller compared to the United States. So I just don’t think that we’re really comparing apples to apples here.

Circling back to the possibility of a vaccine—when families will be able to reunite without worry—what’s your prognosis on the timing for one?

There’s been tremendous progress on the vaccine front. I think it could be months to a year, but I don’t think it’s years away. It could even arrive in the first part of 2021.

Next, an etiquette expert reveals how to handle social distancing rule breakers.