So far, the new coronavirus seems to be an equal opportunity pathogen, at least when it comes to who gets infected. It doesn’t seem to single out certain groups or individuals. “There’s not a difference in risk of transmission that we know of,” says S. Wesley Long, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and genomic medicine at Houston Methodist Hospital.

There is, however, a difference in who is more likely to get seriously ill or have a greater risk of dying from COVID-19. While 80% of people will have mild (or even no) symptoms, it’s thought that about 20% will get seriously or even critically ill. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high-risk groups include older adults along with people who have serious chronic medical conditions.

That means 41 per cent of adults aged 18 and over are at high risk from COVID-19 either because of their age or an underlying medical condition, says a new report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

People who are elderly

According to a report from the Chinese Center for Disease Control, people 80 and above with COVID-19 had the highest mortality rate, at 14.8 per cent, compared to an overall rate of 0.9 per cent in China at that time. Bear in mind, these figures are from February 17 and the numbers are changing rapidly. The mortality rate appears to rise dramatically after 65, says Dr. Long.

This is partly because as we age, the internal organs just don’t work as well as they used to, adds Dr. Long. It also has to do with the natural decline of the immune system over time. “As you get older, your immune system is not as potent as when you were young,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, at a March 13 news conference.

People who have heart disease

The Chinese report found that the mortality rate was 10.5 per cent in people with COVID-19 who also had cardiovascular disease. About 6 per cent of people with COVID-19 and hypertension (chronic high blood pressure) also died. “The virus has the potential to attack not only heart muscle, but blood vessels as well,” says Robert Glatter, MD, emergency physician with Lenox Hill Hospital, New York City.

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), 40 per cent of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (people who are hospitalized are likely to have much more serious disease) had cardiovascular disease or cerebrovascular disease (such as stroke). The AHA also states that the virus may disrupt plaques (basically fatty deposits) that have built up in arteries. This would raise the risk of a heart attack. (Here’s how to boost heart health in general.)

People with lung disease

As experts feared, people with chronic respiratory disease have been more vulnerable to COVID-19: In China, 6.3 per cent of people who had an underlying respiratory condition died from the infection. The virus focuses its attack on the structures and tissues that are involved with breathing. Complications include “not only developing severe pneumonia, but ARDS [acute respiratory distress syndrome], which prevents lung tissue from being adequately oxygenated,” says Dr. Glatter.

Lung diseases that carry a higher risk of COVID-19 complications include asthma and COPD, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which includes both chronic bronchitis or emphysema. (Smoking is the main—but not only—cause of COPD.)

“Asthma is definitely a risk,” says Dr. Long. “Asthmatics tend to have a slight impairment of lung function even when they’re not symptomatic. On top of that, for a lot of asthmatics, any sort of respiratory infection is a trigger for airway inflammation and for basically having an asthma attack.”

People with diabetes

Diabetes along with other endocrine disorders can also put people at risk of more severe illness or death from COVID-19. The report on cases in China put the mortality rate at 7.3 per cent in people with diabetes who had COVID-19. (Tom Hanks, who tested positive for the virus and is currently in isolation in Australia, has type 2 diabetes.) The risk is likely similar for both types 1 and 2 diabetes, says the American Diabetes Association.

“People who have diabetes also tend to have other underlying complications unless it’s beautifully managed which isn’t typically the case,” says Libby Richards, PhD, RN, associate professor at Purdue University School of Nursing in West Lafayette, Indiana. “Your body is already under stress. That just decreases your ability to fight infection.”

(Learn to spot the signs you might have diabetes.)

People taking immune-suppressing drugs

Anyone taking drugs that dampen the immune system is going to have more trouble fighting off COVID-19 and its complications. This includes people with HIV/AIDS, transplant patients, anyone taking high-dose corticosteroids, and cancer patients undergoing treatment, says the CDC.

“Most chemotherapies work by targeting rapidly growing cells and some of the most rapidly growing are blood cells,” says Dr. Long. And blood cells are critical to making sure your immune system works in high gear.

People with autoimmune diseases such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis also need to be especially careful. The reason the newer biologic drugs work so well for these conditions is that they tame the overactive immune systems that are driving the diseases.

(These are the telltale lupus symptoms you should never ignore.)

People with other chronic conditions

People with any other form of chronic disease are also likely to suffer disproportionately. This includes chronic liver disease and chronic kidney disease, says the CDC.

“These conditions impair the body’s natural capacity to cope with infection,” says Dr. Long. People with long-term conditions also have impaired immune systems, the AHA adds.

People with other conditions

People with certain blood disorders, such as sickle cell anemia, and people who take blood thinners may be at higher risk for complications from COVID-19, says the CDC.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse also cautions that people who abuse drugs may be at higher risk, though we may not have enough tests results yet to confirm this. People who smoke tobacco or marijuana or who vape are already putting their lungs at risk, while opioids and methamphetamines put stress on the respiratory system. Add to that the increased risk of homelessness and incarceration which can up the risk of getting COVID-19. Next, find out how doctors are protecting themselves from coronavirus.

Checking the mail

It’s become an everyday part of life in modern society to go outside and check the mailbox to see if any mail has come in. However, as you’re going through envelopes from friends, loved ones, and magazine subscriptions, the thought may cross your mind: just how clean are your packages and envelopes, anyway?

How clean are your packages?

Armed with hand sanitizer, wet wipes, and the classic hot soap and water, it still takes a lot of time and effort to clean, sanitize, and disinfect everything in your vicinity. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide a lot of tips and information on their website including this guide on when and how to wash your hands. Even though there are still a lot of unknown variables regarding the novel coronavirus, named COVID-19, the CDC can still use insight from previous coronaviruses like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV as a reference and guide.

According to the CDC’s FAQ section on its website, it doesn’t seem likely that the coronavirus can spread through packages sent through the mail. “In general, because of poor survivability of these coronaviruses on surfaces, there is likely very low risk of spread from products or packaging that are shipped over a period of days or weeks at ambient temperatures.” However, it’s still a good idea to wash your hands, especially after touching these 10 things.

If you’re concerned about COVID-19, your Amazon package will most likely be OK by the time it reaches your doorstep. “Coronaviruses are generally thought to be spread most often by respiratory droplets,” the CDC website continues. “Currently, there is no evidence to support transmission of COVID-19 associated with imported goods and there have not been any cases of COVID-19 in the United States associated with imported goods.”

But could coronavirus transfer from your mail carrier to your package, and then to you? “If they have the virus, and there are droplets transmitted to the package, it is theoretically possible to get the virus since it can live on surfaces for up to nine days,” Darshan Shah, MD, founder and Medical Director at Next Health, tells Refinery29. But, again, while it’s possible, it’s still unlikely. Here are 4 household products that kill coronavirus, according to Consumer Reports.

Cleaning out your mailbox

Your email inbox isn’t the only inbox that needs to be cleaned. Your physical mailbox needs to be cleaned, too. Angie’s List recommends mixing a few drops of dish soap with warm water and cleaning both the inside and the outside of the mailbox to remove dirt. Once wiped down, disinfect the surface with the appropriate disinfectant spray. Next, make sure you know the best ways to clean your house to avoid getting sick.

Mrs. Bradbury’s Boarding House

I’m sitting at my shiny white kitchen table, round and bright as a happy face, and talking to Sara, my boarder. Sara’s face is not happy, and one of the perils of turning your home into a boarding house is an unhappy tenant.

Sara is sad because she thinks my squat stucco house in Toronto, where she began renting a room in the summer of 2017, is infested with bugs.

“It’s just the occasional fly because I don’t use screens,” I say, waving my hand at the flung-open windows. A summer breeze eddies around us. “So.”

The So is for finality, to get Sara out the door to the University of Toronto lab where she spends long hours dissecting brains for her PhD thesis, because as I speak an enormous insect is rappelling from the ceiling toward Sara’s hair, its arms snapping hungrily.

“But you see here,” Sara’s brown eyes well with worry as she rolls up her pant leg to reveal a large red welt. “It is—what is the word?”

“Oozing,” I say. Sara speaks excellent English, with only an occasional lost phrase. (“I wish you could understand me in Persian,” she once said. “In Persian I’m witty and sophisticated.”)

“It’s just a mosquito bite,” I say, and hope this is true. The Volkswagen-sized bug—are those pincers?—is now inches from her head. “Stop scratching.” As the owner of a boarding house, I am allowed to say bossy things like this.

Sara rents a room in my home, on the second floor. Peter, a lovely, soft-spoken teacher and musician, is in the basement apartment. Until last March, my son Kelly lived in the bedroom beside Sara’s. He’s a grounded young man with a quick mind. Home between travel and work as a web developer, Kelly played the role of the household pragmatist.

Housing so many entitles me to be smugly satisfied that I’m on the supply end of the country’s rental demand. You’ve heard the numbers. In 2018, Toronto and Vancouver’s vacancy rates were sitting at around 1 per cent, but the problem is far more widespread. The same year, Prince Edward Island’s available rental stock for a three-bedroom apartment was zero. You read that right. With a national vacancy rate of 2.4 per cent at last count, we have a coast-to-coast renting crisis. Meanwhile, longtime homeowners such as myself rattle around in our Miss Havisham manors, empty now with the kids grown.

I’d like to say that guilt over my greedy set-up is why I opened Mrs. Bradbury’s Boarding House, but the truth is I was having trouble sleeping. The house had been broken into twice, the second time in mid-afternoon as I sorted bills at the dining-room table. My bag was on the window ledge, and the thief hoisted himself halfway through the open window before he saw me sitting there. He paused, calculated his timing, and grabbed my bag before I could lunge from my chair. I have to say I admired his follow-through. I didn’t know whether to call for help or ask for his resumé.

After that, I woke up thinking how sad it would be to be murdered. Finding a boarder was a solution to a practical problem. I needed a good night’s sleep.

My decision to take in roomers was not met with widespread approval. “Mom. No.” My daughter Mary was alarmed by my lack of self-knowledge. I was letting her old room and needed her to box up her kindergarten art projects. “You don’t even like people,” Mary continued. “You especially don’t like people in your own space. Who make messes. And talk to you.” Perhaps I had once or twice terrorized Mary’s friends who specialized in all of the above. I may have been known as Scary Mommy for a couple of their teenage years.

Laura, my sister who lives nearby, worried about safety. She didn’t get the concept of taking in roomers so I wouldn’t be murdered. Opening my house was opening myself to the vagaries of the universe. “What you want is a graduate student,” she decided. “Quiet, female. Try U of T housing.”

Clear ground rules came up a lot with friends pondering something similar: the living room’s off limits, assign food shelves, no talking in the morning—especially not to me, apparently.

Worse than the character analysis was the pitiless mockery. Think of those too-genteel boarding-house women unsparingly fictionalized by James Joyce, William Trevor and Arthur Conan Doyle—believe me, I did. “How’s our Mrs. Hudson?” became a standard greeting.

It turns out, however, that I am now on trend: I am progressive and modern instead of marginalized and batty. Toronto HomeShare, launched in 2018, is a city-funded project that takes on intergenerational home-sharing. It’s a two-birds, one-stone solution, matching seniors with too much space to students with too little money.

To our south, Nesterly, a startup in Boston, is betting intergenerational home-sharing can be a profitable business. “Housemates can exchange help around the house for lower rent.”

I have had three roomers so far, and chores around the house are not part of the equation. Like me, they are far too busy. Rebecca, comedian and acquaintance in town for a few months from L.A. where she worked, was my first toe-dab into the boarding-house lifestyle. Rebecca would enter my large wooden front door with a lusty “Hel-oo-oo!” and bang out a couple of tunes on the piano in the pauses between her brilliantly paced stories about shopping for tampons. You knew when Rebecca was home, in other words.

Yulina, Boarder #2, was so quiet I could rarely tell whether she was at home in her room or at school. She responded to an ad I posted at U of T housing and checked all of Laura’s boxes. She was pursuing an undergraduate degree and has previously worked in London and Frankfurt. Originally from South Korea, she has the not-quite-present look of someone getting ready to make her next move—Yulina arrived and departed with the same compact suitcase. After nine months, she was slightly chattier, and to her this was a transformation.

“Cathrin, can you believe how shy I was when I first came? And how different I am now?” She wasn’t the only one in transition. My hair no longer caught fire if Yulina was already at the kitchen table when I came down in the morning. We even chatted over coffee.

Sara was next. She is perhaps the least chore-oriented of the three so far, although not for a lack of willing spirit. Sara arrived with quite a lot of luggage. I was not kind about this. “You’re renting a room, not half a house,” I said, and grudgingly agreed to let her add a few of her favourite dishes and pots to my tightly orchestrated kitchen. Ixnay to her stacks of Tupperware. This is the other peril of running a boarding house: you find out the ways in which you are a tool.

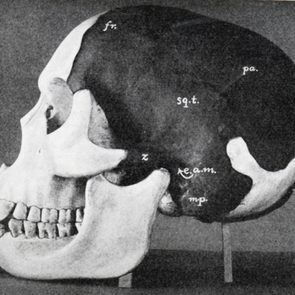

One thing Sara didn’t arrive with was a knowledge of daily practicalities. My son and I have secretly wondered if she is perhaps an Iranian princess. She once asked if she could put gold-gilded china in the oven at 350 F, and another time started a small kitchen fire after she put her dinner to boil on the gas stovetop and wandered off to think. She has a lot to think about. Her doctoral specialty is the interconnectivity of brain tissue.

“What have you learned?” I asked her early on.

“Nothing,” she said, and hid her face in her hands, ever modest. “Imagine standing in the vast ocean with a teaspoon of water in your hand. That teaspoon is how much we know about the brain.”

“Well, it’s kind of like a computer,” Kelly said, and I imagined carrying around the latest Apple upgrade on my shoulders. “The brain is nothing like a computer,” said Sara. “You can’t find a storage bank in a brain, for example.” She and Kelly would discuss this for the next hour.

I gave up a few things taking in boarders: having the bathroom to myself, blaring Leonard Cohen at full blast, and my own space, which turns out to be less valuable than I once thought it was. But as I have come to know Sara, I understand how much more she’s left behind. She never watches The Handmaid’s Tale, for example, because it is too much like modern-day Iran. “My friends and I lived this.”

She swam in the Caspian Sea as a girl, and longs to swim in a northern Ontario lake. One weekend she rented a car and drove north with her mask and snorkel, turning down road after road on Lake Joseph in Muskoka only to end up at the bottom of another cottager’s driveway. She came home defeated, unable to find a public place for a swim. I was terribly hurt by her disappointment, and I began to understand her isolation. Being Mrs. Bradbury of the boarding house, my first impulse was to fix it.

But some things don’t fix easily, and Sara understands this better than me. When she is homesick she brings out her bag of Cheetos—and I mean one bag. She unfailingly offers to share it. “It’s console eating?” she says. “Consolation eating,” I say. It was Kelly who noticed that, in the first few months of her stay, she never ate more than three Cheetos at a sitting. “She’s had that bag for three months.” They are friends now, and will remain so, I think. It makes me happy to come home to them talking about brains or Trudeau or whether crunchy or puffy is the best Cheetos style.

That December, Sara invited Kelly and me to celebrate Yalda, the winter solstice. She prepared a spread of sweets, nuts and pomegranate, served with a silver spoon, and three kinds of tea: sour orange blossom, gol gavzaban and camomile.

“My father would say I have done it all wrong. The tea is not fresh enough, the colour should be dark red, not black, and so on. He is the master of this.” Sara’s parents are still living in Iran. They refuse to suffer the border interrogations and indignities that travelling to North America entails. In May 2017 they had met for a holiday in Istanbul, Turkey being one of the few countries to which Iranians can travel without a visa.

Sara came home with two beautifully wrapped teas, from her mother to me. One to calm me down, and one to bring me peace. Apparently these are different, but I felt I needed both. When I wrote Sara’s mother to thank her, I told her what a privilege it was to have Sara in my home.

Yasaman wrote back that she wished she’d been in my kitchen to make the tea for me. “I cried when I read the part you wrote about Sara. She is my first daughter and she has made all the dreams I had for her come true. She makes an effort to be the best in every aspect of her life.”

Sara has made me better too, more aware of the way I take my world—my home, my dishes, my access to northern lakes—for granted.

If there are actual dangers to taking in boarders, I haven’t encountered them. Instead, the world feels kinder, smaller and more personal. Yasaman closed her letter by inviting me to visit Iran. I hope to take her up on the invitation, and any more that might come by way of my boarders.

© 2018, by Cathrin Bradbury. From ‘‘Amid the housing crisis, I took in boarders. Next came the pitiless mockery,’’ (The Star, October 3, 2018). thestar.com

Published March 17, 2020

Avoid these coronavirus scams

We love to see the world with rose-coloured glasses: people are nice, everyone is friendly, and the planet is a good place. But every now and then, we’re reminded not to be so naive. Ever since the coronavirus popped up its ugly, germ-filled head, scams have occurred on just about every platform, from Facebook to Amazon.

“As with any news story, criminals will use this as a pretext for scams,” says Alex Hamerstone, GRE practice lead at TrustedSec, an ethical hacking firm hired by Fortune 500s to try to hack into networks and employees to prevent real attacks. “Coronavirus also preys on people’s fears, so it really is the perfect storm for a scam pretext.”

Impersonating emails

When it comes to online scams, the biggest risk consumers and businesses will face is from phishing emails that impersonate the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, or other health agencies and insurers, says Karim Hijazi, CEO of Prevailion, a company specializing in intercepting data from hacker networks.

“Cybercriminals have a lot of resources at their disposal nowadays which enables even less sophisticated crews to carry out rather advanced phishing campaigns,” Hijazi says. They can buy phishing kits and malware tools online, rent botnets to launch their attacks and find bulletproof hosts to support their malicious domains. “What the average person needs to realize is that phishing scams may often look identical to the same thing,” he says.

Vaccination offers

Now’s the time that you may see ads offering prevention, treatment, or cures for the coronavirus, says the U.S.-based Federal Trade Commission. (FTC). Sounds too good to be true? It is. And if there’s a really big medical breakthrough, the last place you’ll hear about it is via an ad sent to your inbox in the form of a sales pitch, the FTC says.

Consumers should look at the return path in the email to see where it really does originate from, Hijazi says. “Hackers can easily spoof any domain they want in the email header that shows up in your inbox, but they can’t do that with the return path,” he says. “If the return path shows a different domain or email address, then you know it’s a trick.”

Look for warning signs

These will appear on the websites you visit, Hijazi says. “Criminals often use a technique called “combosquatting” to create malicious websites that may appear to be a legitimate domain,” he says. Often what they will do is to hyphenate or add a period after the business name, then insert a new word like “sales” or “discount” to create an entirely new domain. For example, Bigboxtretailer.com could be hyphenated to Bigboxretailer-deals.com.

“To the average person, that will appear to be the real website of Big Box retailer, when in actuality, it is an entirely separate domain controlled by the hacker,” Hijazi says. If companies don’t register all the combinations and variations that can be created from their website domains, they leave their customers exposed to this type of scam. Hijazi suggests checking the WHOIS registration of a website to verify the real owner.

Don’t respond right away

“Scammers depend on you reacting before you can carefully consider things,” Hamerstone says. Instead, think for a bit and try to discern whether it’s too good to be true, whether anything sounds odd (maybe someone is misspelled, maybe the grammar is incorrect, etc.). Then, ask a friend or family member to offer a second opinion.

Go straight to the source

If you get an email raising money for an organization, don’t click on the link in the email, Hamerstone says. Instead, use your browser and go straight to the organization’s website. Same for phone calls. Instead of responding directly to the call and giving credit card info to that person, call the company back on its mainline to make sure the offer or fundraiser is legitimate.

High priority good offers via email

Expect to see special offers on high-priority goods like hand sanitizer and face masks, Hamerstone says. Or a sender could also claim to represent the local hospital and are warning you about a personal contact who has recently tested positive for coronavirus. There are many schemes they could use to convince you to open an attachment, click on a link, log into a website or provide information over email.

Does it pass the smell test?

“There is a very simple way to spot a scam,” Hamerstone says. “Does it pass the smell test?” This means, ask yourself: Is this offer too good to be true? Is this an unsolicited communication on social media, or on your phone or by email? “People are used to doing everything over email these days, but always remember that the government does not send you attached files,” Hamerstone says. So the CDC is not going to email you a PDF or Word document with data about local infections in your area and Tthe state health department is not going to send you a zip file. They’re also not going to request your social security number over email.

Be wary on Amazon

With Amazon’s site, it’s often difficult to tell who the seller is, Hamerstone says. This gives every seller a certain amount of legitimacy and it becomes harder for the buyer to tell whether or not they should be concerned, which is why it’s very important to check on who the seller is.

On Amazon, there are two points of data: the maker of the product and the company or person who is actually selling it to you. The seller is listed right under the “Buy now” button. Click on the seller’s link and check out their Amazon page. “Ideally, you want to stick with third-party sellers who have been active on Amazon for a long time, have a large number of positive reviews, and there is consistency in their offerings,” Hamerstone says. You should also try to avoid buying important items like medical devices from third-party sellers who don’t appear to have much experience in the medical field. The safest bet is to stick with items that are labelled “Ships and Sold by Amazon.ca.”

From NerdWallet

I feel I have a unique perspective on this subject because I was a car salesman and, later on, I was a car buyer for an automotive testing website.

Over the course of more than a hundred transactions, I came to admire the benefits of working with a good car salesperson. The right professional can save you time, money and, yes, even turn this normally grueling process into an enjoyable experience. Working with the wrong salesperson can be a costly mistake—literally—and land you in the wrong car with a money-sucking loan.

But how do you know? Here’s what I look for—and look to avoid—when I first meet and test drive a car salesperson.

A good car salesperson…

- Values your time. Before you go to the dealership, call ahead and tell the sales manager which car you want to test drive. Ask for the name of the salesperson you’ll be working with and if they can pull the car out and have it ready for you to drive. If the salesperson and car are ready for your appointment, you’re off to a great start.

- Listens to you. Choosing the right car is about you and your needs. So ask your prospective salesperson a question you might already know the answer to. Does the salesperson let you finish talking without interrupting? Is the response accurate and on point? Does the salesperson wait to see if you have additional questions before moving on?

- Knows their product. Picking the right car means searching countless choices—trim levels (base, sport, limited, etc.), engine sizes and option packages. Asking a comparative question is a good test: “How is the sport trim different than the base model?” An informed salesperson will answer with specifics and even explain how the features work.

- Follows up promptly. If the right car isn’t immediately available or you need to come back later to conclude the deal, take the salesperson’s card and get their cell number. Call or text the next day. If you don’t reach them, leave a message and expect a prompt response. Even on days off, salespeople should return calls.

- Doesn’t lie to you. You’ll have to use your intuition for this one. But you can also rely on other people’s judgment by getting referrals and checking Yelp and online reviews.

A bad car salesperson…

- Sizes you up to gain an advantage. Salespeople are trained to “qualify” customers, or learn as much about them as possible to create leverage when negotiating. Seemingly innocent questions, such as where you work, may determine whether the next question is, “Do you have a payment in mind?” or “What kind of vehicle did you have in mind?” I meet these kinds of questions with vague answers like, “Oh, I’m in communications …”

- Uses language that traps you. Salespeople are trained to use your own answers to limit your ability to say no. For example, if you say the car is too expensive, their answer is, “OK, but besides the price, is there any other reason you won’t buy this car?” Don’t work with a salesperson who tries to manipulate you just to close a deal.

- Baits and switches. A salesperson’s job is to get you in the door. Your call, email or text to ask about a particular car or deal is most likely to be met with a “Come on down and drive it.” But if the car or deal evaporates when you arrive in person, you’re dealing with the wrong salesperson.

- Wastes your time. You’ve been on the lot browsing for five minutes and a nearby group of salespeople is talking and laughing without looking in your direction. Not a great start. You’re tempted to call one over to help you take a test drive. But a good car salesperson will make a timely, low-pressure offer of help.

- Pressures you. This is what shoppers fear and abhor most, and it takes many forms. For example, at the dealership I worked at, we were trained to tell the customer, “Follow me!” and march them into the sales office before even taking them on a test drive. If they followed, it showed I could control them. If you experience any form of this manipulation or pressure that makes you uncomfortable, head for your car and don’t look back.

More From NerdWallet:

Extended Car Warranties: When and How to Say No

How to Make a Student Loan Complaint That Gets Results

Should Your Student Loans and Your Spouse’s Get Hitched?

Philip Reed is a writer at NerdWallet. Email: [email protected]. Twitter: @AutoReed.

The article How to Spot a Good Car Salesperson — Or a Bad One originally appeared on NerdWallet.

Published March 13, 2020

Coronavirus in cats

It’s hard to escape news of the coronavirus these days—and if you have pets, you’re probably not only worried about the possibility of contracting the virus yourself, but also about coronavirus in cats.

Cat owners have most likely heard of coronavirus before—cats are routinely vaccinated against a species-specific strain of the virus that can cause mild digestive issues. But according to Zac Pilossoph, DVM, Healthy Paws Pet Insurance consulting veterinarian, in rare cases, this common feline coronavirus infection can turn into something more troubling.

“In less than one per cent of cats, there is a chance that they can develop a more severe type of coronavirus, called feline infectious peritonitis or FIP, which is fatal in almost 100 per cent of cases,” he explains. “FIP occurs via the virus mutating within the individual cat alone and finding a way to evade the normal immune system.” The better news is that FIP is not transmissible between cats.

COVID-19 and your cat

So far, it has not been proven that an animal can transmit COVID-19 to humans. There are several zoonotic diseases, or diseases that can be passed from animals to humans, the most well-known of which is rabies, but at this point, COVID-19 has not been found to be zoonotic. Nor has it been found to be anthropozoonotic, or transmissible from humans to animals, according to Dr. Pilossoph. “Continuous testing is being done globally on a regular basis to determine if this remains the case,” he says.

A dog in Hong Kong who recently tested positive for COVID-19 was most likely a passive carrier, says Dr. Pilossoph. “A passive carrier is a living creature that can help spread disease from one animal to another, without ever becoming infected themselves,” he explains. “To demonstrate the concept of passive carriers, pretend you were infected with the COVID-19 virus and you decided to snuggle your outdoor cat before letting it outside to roam the neighbourhood. Your cat, for a short amount of time, could pass virus particles to any human who subsequently pets them.”

In this scenario, your cat was a passive carrier for coronavirus infection, he says. “If you performed a coronavirus test on that same cat, it may test weakly positive, not because it’s infected with the virus, but because the virus is on them from your snuggle session.”

What should cat owners do to protect their pets?

For now, pet owners need not worry about their cats becoming infected with COVID-19. Since the virus has not been shown to pass from animals to humans, your four-legged friends are safe. That said, Dr. Pillossoph recommends keeping your cats close as a roaming cat could potentially become a passive carrier if it comes into contact with someone who has been exposed, which could then expose you.

As always, remember to follow these guidelines: wash your hands frequently, avoid touching your face, cough or sneeze into tissues or your elbow, and try to keep at least six feet away from people who are coughing or sneezing themselves.

Window or aisle?

One of the most important decisions you can make before your flight is not only figuring out where to go and when, but also where to sit on the plane. If it’s important for you to stand up often and stretch during the flight, then maybe the aisle seat would be best. If you’re stuck in the middle seat, then you can take comfort in knowing the proper etiquette rules allow you to have both armrests. If you select the window seat, then you can take look out the window at the scenery passing by below you.

On your journey, you could even contemplate why some airplane windows have little holes. All of these seats have great options for different reasons. If you do decide to sit in the window seat, you’ll be relieved to know that it’s the best seat on the plane to avoid getting sick.

The best seat on the plane… For health reasons

Recirculated air throughout the cabin isn’t the culprit for people getting sick on planes. Turns out, germs are spread by people moving about the plane. In a 2018 study published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, research showed that for people sitting in aisle seats, the average number of contacts is largest, followed by middle seats, and is the lowest in window seats. This news is even better if you happen to be lucky enough to find yourself in a window seat with no seatmates next to you. So, next time you’re looking to avoid germs, booking the window seat might be the way to go. Staying hydrated, taking an immune system booster, and avoiding caffeine are just a few things flight attendants do to never get sick.

“With over 3 billion airline passengers annually, the inflight transmission of infectious diseases is an important global health concern,” the study reads. “Over a dozen cases of inflight transmission of serious infections have been documented, and air travel can serve as a conduit for the rapid spread of newly emerging infections and pandemics. Despite sensational media stories, risks of transmission of respiratory viruses in an airplane cabin are unknown. Movements of passengers and crew may facilitate disease transmission.”

If you’re sick, it’s a good idea to wear a face mask. “When you cough or sneeze, you’re ejecting fine particles,” Vicki Hertzberg, an Emory University biostatistician who, with scientists at Boeing, conducted the study, tells NPR. “Other people near you can inhale them. They can get them on their hands. They can land on their tray tables.”

However, is there a seat that trumps the window seat? Yes, and that’s a seat as far away from a contaminated person as possible. “Though really, the best place to sit is away from any passenger who’s coughing or sneezing. There was a perimeter around the person with increased risk,” Hertzberg tells NPR. “Everywhere else, the risk of getting sick was minimal.” No matter where you sit, think twice before touching the air vents above your seat, which are arguably the germiest spot on the plane. (Here’s more airplane trivia you’ve always been curious about.)

What if someone is sick on a plane?

To manage passengers with influenza-like symptoms, the World Health Organization recommends that “persons on board who may be suffering from a communicable disease, especially if they have influenza-like signs and symptoms, should receive immediate attention.” It’s important to wash your hands—after all, here are 14 diseases you can prevent just by washing your hands.

What could go wrong?

I’m an occasional catastrophizer. Facing my first cross-Canada flight with my plus-sized feline, Lance, brought the “cat” part of my condition to the fore.

Planning for the trip involved slightly less preparation than a Sahara trek. My mind pinballed around all the things I couldn’t control, such as the possibility that a 10-year-old, 10.5-kilogram tabby (down from nearly 12 kilograms; don’t judge) would produce a great, noxious poop at 30,000 feet.

Perhaps it would be somewhere over Winnipeg. A planeload of passengers would hate me.

What if Lance launched into his signature premeal wailing or those convulsive, strangled sounds that often serve as the opening act for a dramatic hairball delivery?

The flight was the final step in the decision my partner, Hans, and I made to move from Toronto to Victoria. All the stressful unknowns around this life change, including selling the house, hiring cross-country movers, shipping the car west by train, saying goodbye to friends and the city that had been our home for more than 35 years—all of that was a cakewalk compared to the anxiety I felt about getting a skittish cat onto a plane and keeping him calm during the process. Keeping me calm while trying to do that would be a bonus.

Neither of us would be sedated. The same vet who explained that Lance’s girth stems from being “food motivated” warned us that a zonked-out cat can suffer even more when he’s terrified and immobile.

So we bought a bottle of pheromone spray designed to calm cat nerves. I dosed Lance’s carrier repeatedly and considered spraying it on myself.

I was so twitchy thinking of all that could go wrong with Lance, the move almost took a backseat.

Air Canada charges about $50 to fly your cat or small dog in the cabin on domestic flights, which is a sweet deal. For the aircraft we were taking, the rules state that the pet carrier must measure 21 x 38 x 43 centimetres, weigh less than 10 kilograms and fit under the seat in front of you.

Lance becomes luggage

We were overly optimistic about Lance’s dimensions from the get-go. I ordered an airline-approved carrier online that arrived looking laughably small next to Lance’s sprawl. He’d been on a strict regime of diet cat food for a year, so he wasn’t going to shrink any time soon.

I inspected the underseat area on every flight I took leading up to our move, mentally imagining Lance down there. I worried about how he would handle the experience and quizzed flight crews and other pet-parent passengers.

I decided there was no way Lance would fit under a WestJet seat. Air Canada seats on some flights were roomier.

Carrier-wise, the only thing that would work was something we call Lance’s “little blue house”—a soft-sided pet cage. Using treats (of course) and advised by YouTube videos, I attempted to train him to hang out in the carrier in the hope he’d be happy to travel in it. That was a fleeting dream. But he liked it well enough for naps. If I took two of the three flexible ribs out of little blue house, it could be (mostly) squished under the seat.

Hans would be responsible for carrying Lance onto the aircraft, while trying not to look like the carrier weighed enough to dislocate his shoulder.

I planned to board with a small purse, while the cat would have a wheeled carry-on suitcase lined with an aluminum roasting pan for a makeshift litter tray in case the flight was cancelled or delayed. The interior was jammed with litter, kibble, pee pads, plastic bags, latex gloves and a towel and change of clothes for me in case there was an unfortunate feline incident.

That’s one cool cat

We closed the door on our Toronto house for the last time on a rainy afternoon, sliding the key in the mail slot as I cried sloppy tears fuelled by emotions and stress. Lance quietly meowed a few times in the SUV as we started our drive to the airport. Then he curled up and went to sleep. Let’s hear it for the pheromone spray.

Security at Pearson was the first test. Did I mention that Lance tends to let fly a horizontal stream of urine when he’s nervous?

I had to take him out of his carrier to go through the security scanner. I brought a harness and leash, in case he was tempted to bolt. But if getting Lance into his carrier was often a trial, getting him out in a busy airport would be worse.

“My cat is a projectile pee-er when he’s nervous,” I told the security officer.

He and his colleagues found this hilarious. They led me to a private screening room, where the newly laid-back Lance was easily parted from his carrier.

Lance did not pee. He was quiet. And he went back into his little blue house willingly.

He slept in a corner of the Maple Leaf Lounge while we waited for boarding, occasionally looking out the mesh panels to watch the world. He accepted pettings. He was the same cool cat in the departure area.

Quiet and content, he even purred occasionally during the flight. He didn’t entirely fit under the seat, and many thanks to the flight attendant for failing to mention it. He didn’t care about turbulence, takeoff or whether there were decent in-flight movies. Lance, I discovered, is an absolute champ at air travel. As it turned out, being with us was all he needed. The snoring cat at my feet reminded me it might be a good plan to occasionally let life just unfold.

Eleven hours after locking our Toronto front door for the last time, we walked into our Victoria apartment. I set up a litter box, water and dinner for Lance—and a large glass of British Columbia pinot noir for Hans and myself.

We were home.

© 2019, Linda Barnard. From “How to pack your fat cat as carry-on luggage,” The Globe and Mail (August 6, 2019), theglobeandmail.com.

Published Mar. 11, 2020

As confirmed cases of coronavirus continue to grow across Canada, it’s natural to worry, at least a little, about whether you and your family will stay healthy. And, of course, that includes thinking about the possibility of coronavirus in dogs.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), coronaviruses are a large group of viruses that can sicken people or animals. Coronaviruses are responsible for the common cold, as well as the SARS outbreak in 2003. This newest strain of coronavirus is known as COVID-19.

But do you really need to be as concerned about your retriever as you are about your kids? Here are answers to the questions about canine coronavirus that dog parents have been asking.

Should I worry about the spread of the new coronavirus in dogs?

No, at least not at this time. Spokespeople from both the WHO and Public Health Agency of Canada have stated that there is no evidence that pets can spread COVID-19 to other pets or people.

Available data on recent dog illnesses in the United States seems to confirm that, too. Pet medical insurance company Trupanion monitors such data on a “very granular” level daily, and by breed and location, explains Mary Rothlisberger, vice president of analytics. “We are on top of any health-related trends that might be out of the norm. We have not seen any increases or changes in the frequency of illnesses that would appear unusual,” she says.

But what about that dog in Hong Kong?

Yes, one older male dog in Hong Kong tested as “weakly positive” for the virus in late February, although WHO officials recently reported that the dog never showed symptoms and is doing fine. His owner had contracted COVID-19. To date, he is the only dog in the world to have tested positive for canine coronavirus.

“The dog had low levels of the virus in its nose and mouth… and could have picked it up from the patient with the virus—or from surfaces he had touched,” says Rachel Barrack, DVM, CVA, CVCH and founder of concierge practice, Animal Acupuncture in New York City, further explains. “Since dogs’ noses and mouths come in contact with just about everything, it is hard to say.” WHO will continue to study the situation, but for now maintains there is no evidence that household pets can transmit the new coronavirus.

Aren’t there other types of coronavirus in dogs?

“The most common strains of coronavirus that affect dogs are canine enteric coronavirus, or CECoV, and canine respiratory coronavirus, known as CRCoV, neither of which can be transmitted to humans,” says Jamie Richardson, DVM, medical chief of staff at Small Door Veterinary in New York City. CECoV causes mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

Signs of a CRCoV infection, better known as kennel cough, are cough, fever, or breathing difficulties, says Sabrina Kuo, DVM, a veterinarian who owns Chicago’s West Loop branch of GoodVets.

“Survival rates of both [types of canine coronavirus] are high,” says Dr. Richardson. “Almost always, the symptoms of these two strains are mild and pets typically recover on their own.” But as with most other infections, complications can crop up for pets with other underlying health conditions and the very young and very old. It’s always smart to be aware of these secrets your dog’s tail is trying to tell you, too.

I know the odds are low, but what would be the symptoms of the new coronavirus in dogs?

Since there are no actual cases of canine COVID-19, it is hard to say what the symptoms would be like, asserts Dr. Barrack. “If you have a pet that becomes sick after contact with people infected by COVID-19, it is important to contact your veterinarian, but remember it is highly unlikely that a dog, or a cat, could be infected,” she adds.

Is it OK to bring my small dog in a carrier on a domestic flight?

“There are no necessary precautions for travelling with a dog during this coronavirus outbreak other than those you would usually take,” says Dr. Barrack. She points to these guidelines:

- Check that your dog’s carrier meets your airline’s requirements, which you can find on its website.

- Dogs must be at least eight to 12 weeks old to fly, depending on the airline.

- You’ll need a health and immunization clearance certificate from your vet. You may be advised against flying with dogs who have cardiac or respiratory issues, epilepsy, blood clots, or hypertension, as well as pregnant or elderly dogs.

- Feed your dog at least four hours prior to flight time to ensure they have had some time for digestion and to relieve themselves. They should have water available in flight.

- Wash your hands, or use a hand sanitizer, right before boarding.

What precautions against canine coronavirus can I take, just in case?

In the unlikely event you or someone in your household does contract COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia urges avoiding contact with your dog, including petting, being licked, kissing, and sharing food.

WHO recommends always washing your hands after playing with or snuggling your dog. COVID-19 aside, salmonella and E. coli can easily pass between pets and their people. And if your dog is sick, “Keep her home and away from dog parks, groomers, and playgroups to limit the spread to other dogs,” says Dr. Richardson.

“There is no need to panic,” concludes Dr. Kuo. “The veterinary community is heavily involved with understanding this rapidly evolving situation and how it affects our pets.”

How did April Fool’s Day start, anyway?

On the evening of April 1, 1957, thousands of British families tuned in to watch Panorama—one of the day’s top current events broadcasts—to witness footage of a happy Swiss family harvesting their prized spaghetti trees. Unbeknownst to many viewers, the four-minute “news” segment, which literally showed strands of cooked pasta dangling from the trees in a family vineyard, was an intricate April Fool’s Day hoax devised by a freelance cameraman and produced for a paltry 100 pounds.

Forget the hundreds of angry letters and bitter newspaper headlines that followed—the show’s staff was “very pleased with [themselves],” having successfully elevated the centuries-old tradition of pranking to a mass-media high.

There’s no question that April Fool’s Day is one of the most widely recognized non-religious holidays in the Western world. Children prank parents, coworkers prank coworkers, and yes, national news outlets still prank their readers. But why? How did April Fool’s Day start and how did it become an international phenomenon?

The totally-legit, not-pulling-your-leg answer is: Nobody really knows. April Fool’s Day is apparently an ancient-enough tradition that the earliest recorded mentions—like the following excerpt from a 1708 letter to Britain’s Apollo magazine—ask the same question we do: “Whence proceeds the custom of making April Fools?”

One likely predecessor is the Roman tradition of Hilaria, a spring festival held around March 25th in honour of the first day of the year longer than the night (we call this the vernal equinox, which typically falls on March 20th). Festivities included games, processions, and masquerades, during which disguised commoners could imitate nobility to devious ends.

It’s hard to say whether this ancient revel’s similarities to modern April Fool’s Day are legit or coincidence, as the first recorded mentions of the holiday didn’t appear until several hundred years later. In 1561, for example, a Flemish poet wrote some comical verse about a nobleman who sends his servant back and forth on ludicrous errands in preparation for a wedding feast (the poem’s title roughly translates to “”Refrain on errand-day / which is the first of April”). The first mention of April Fool’s Day in Britain comes in 1686, when biographer John Aubrey described April first as a “Fooles holy day.”

It’s clear that the habit of sending springtime rubes on a “fool’s errand” was rampant in Europe by the late 1600s. On April Fool’s Day, 1698, so many saps were tricked into schlepping to the Tower of London to watch the “washing of the lions” (a ceremony that doesn’t exist) that the April 2nd edition of a local newspaper had to debunk the hoax—and publicly mock the schmoes who fell for it.

From there, it’s a pretty straight line between lion washing and spaghetti farming. And while we may not know how it started, it’s clear April Fool’s Day speaks to the inner jerk in so much of humanity, and is therefore here to stay.

30+ Car Dealer Secrets Revealed" width="295" height="295" />

30+ Car Dealer Secrets Revealed" width="295" height="295" />