Like many other families in the summer of 2020, Chylisse Marchand and her school-aged daughters, Shay and Alli, spent their days at home. Chylisse’s driver’s license had been suspended after she suffered a seizure, so regardless of the pandemic, they wouldn’t have been able to venture far from their home in the small town of Redvers, Saskatchewan. One of their pets, however, wasn’t tied down by the circumstances, and managed to take an international journey.

Spooky, one of the family’s black cats, has an independent personality. He and his brother, Licorice, had joined the family as kittens in 2013. The cats lived indoors during the frigid Saskatchewan winters. “But the moment spring hit, they loved going outside,” Chylisse says.

Initially, Chylisse wasn’t terribly concerned when Spooky didn’t return from an evening jaunt in the backyard on July 22. “I thought he would turn up in one of our sheds,” she recalls. “That said, we do live close to the highway, so I was a bit nervous that maybe he’d been hit by a vehicle.”

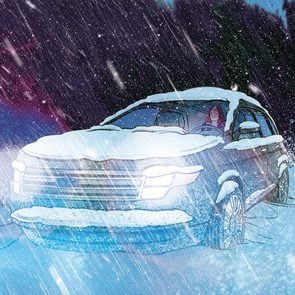

As it turned out, Spooky had climbed into the engine bay of a parked semi-trailer truck. When the truck departed, Spooky became a stowaway. Somehow, he remained unharmed in that cramped space full of wires and hoses while the vehicle drove 230 kilometres southwest to Tioga, North Dakota, then northeast to Manitoba, then back down to North Dakota again.

Meanwhile, there were lots of tears in Chylisse’s home. “My daughters were freaking out,” she says. “Spooky meant the world to us.” He had been missing for about 24 hours when the kids went to bed on July 23. It was late that evening when Chylisse received a call from Spooky’s vet, who told her the missing cat had been found in North Dakota by a trucker named Jack Shao. The vet gave Chylisse Jack’s phone number; she called him immediately.

“He sounded flustered,” she recalls. “He’s an awesome guy, but he’s not a cat person and he didn’t know what to do with this animal.”

Fortunately, Jack’s route would take him back through Redvers the next day. To keep Spooky safe on the trip back home, Jack placed him inside a box with a small opening for airflow.

On July 24, a friend gave Chylisse, Shay and Alli a lift to the local Co-op, where Jack had agreed to meet them. “As the truck pulled up, my girls were beaming,” Chylisse says. “As for me, I just wanted to hug him.”

Besides feeling grateful for a stranger’s kindness, Chylisse was amused that Spooky had crossed the American border at a time when it was closed to everyone except essential traffic. “And the fact that he held out for so long under the semi is unbelievable,” she adds.

As an artist, Chylisse had a collection of her own original artworks, so she gave Jack a print of an old red truck as a symbol of her gratitude.

Upon returning home, Spooky was a little skittish at first, but soon his usual temperament resurfaced. Nowadays, Spooky and Licorice don’t tend to wander far from home. “I don’t know if Spooky learned from his experience or if it’s because the cats are getting old,” she says. “They stay close to the deck and take in the prairie sunset.”

Next, read this heartwarming story of a dog that was lost during a wildfire evacuation—then reunited with her owners.

Fondue comes from the French word fondre, meaning “to melt.” Cheese fondue is made with melted Gruyère, a firm, nutty cow’s-milk cheese with a pungent aroma that originates in a medieval town of the same name.

The cheese melts by simmering in a pot with garlic and dry white wine, for a hearty flavour. A traditional fondue might also use a half-and-half mix of Gruyère and another cheese, like Vacherin Fribourgeois, Appenzeller or raclette. Bread is traditional for dipping, but veggies like baby potatoes and broccoli, steak bites and pear slices are also common.

The dish is traditionally eaten “family-style” out of an earthenware pot called a caquelon. (Modern stainless-steel, cast-iron or ceramic versions are also available.) The pots tend to be wide and shallow to evenly distribute heat.

Where does cheese fondue come from?

The earliest written recipe for the dish appears in a cookbook published in 1699 in Zurich, Switzerland. But at that time, “fondue” referred to a different dish, similar to a cheesy egg soufflé. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that the fondue we know and love emerged.

Today, cheese fondue is the ultimate Swiss dish. But until the 1930s, it was only found in parts of Switzerland. According to Dominik Flammer, author of Swiss Cheese: Origins, Traditional Cheese Varieties and New Creations, it was the efforts of a cheese cartel that brought fondue to broader popularity. A postwar export slump led producers to form the Swiss Cheese Union, which limited competition and campaigned globally for Swiss cheeses. Of thousands of cheeses, the cartel supported a mere seven. You guessed it: Gruyère was one of them.

The union was disbanded in the late ’90s. But by then, cheese fondue’s reputation as the country’s national dish had long been established. It also became a popular wintertime treat in North America: By the early 1970s, fondue was all the rage among young baby boomers.

How to eat fondue like a pro

So whether you find yourself in the Swiss Alps or you want to make your at-home experience feel authentic, here are some do’s and don’ts:

1. Don’t double dip.

2. Stir clockwise or in a figure-eight pattern, never counter-clockwise. Swiss superstition tells us it’s the only way to keep the cheese from curdling.

3. Don’t scrape or tap on the pot; it’s bad manners. Swirl your fork to catch flyaway strings of cheese.

4. The Swiss believe you shouldn’t drink anything other than white wine, kirsch (cherry brandy) or tea alongside fondue because anything else will cause the cheese to congeal in the stomach into a fatty ball known as a “cheese baby.” (A small study in 2010 found that black tea did aid in the digestion of cheese fondue, but alcohol slowed down digestion considerably.)

5. Never lose your chunk in the pot. In Switzerland, whoever commits this faux pas will be half-jokingly handed a punishment such as buying a round of drinks, doing the dishes or taking a shot of kirsch.

Toss your cheese of choice, wine and garlic into a pot and you’ll be well on your way to throwing the fondue dinner party of your dreams.

For more fascinating food stories, dive into this dill-icious history of pickles.

Few senior dogs are as energetic as 13-year-old Sedze, a white and beige Shih Tzu whose name means “my heart” in the Dogrib language, spoken by the Tlicho First Nation. Aptly so, as Sedze has been a beloved member of the Yellowknife-based Cumming family since she was eight weeks old. Despite being in her golden years, Sedze can still keep up with Axel, the family’s nine-year-old German shepherd, on long walks. “Our vet always comments on what good shape she’s in,” says her owner, Louise Cumming, a collections officer for Housing Northwest Territories. “She’s a real trooper kind of a dog.”

In August 2023, the little Shih Tzu’s resilient spirit went through a real-life trial by fire. On August 13, Louise and her husband, Shannon, were shopping for non-perishables and packing up their camping gear in anticipation of an evacuation order. A massive wildfire 35 kilometres west of the city was getting dangerously close and officials were monitoring its path.

Over the previous three months, Canada had been dealing with its worst wildfire season on record. In all, more than 6,600 wildfires were recorded in the country in 2023—1,000 more than the 10-year average.

On August 16, the evacuation order came and Yellowknife’s 20,000 residents were instructed to leave the city. At 9:15 p.m., Louise, along with her husband, daughter-in-law and her daughter-in-law’s best friend, hopped into two cars and a truck with their pets: Sedze, Axel, a husky named Rhea, a cat named Copernicus and a chihuahua named Choco. Along with their clothes, phones and laptops, they made their way onto the Mackenzie Highway, heading south toward Alberta. (Louise’s son, who worked at a diamond mine in the North Slave Region, was to rendezvous with the group later.)

Their destination was an evacuation centre in High Level, a town about seven hours away in northern Alberta, but heavy traffic slowed them down, and thick smoke made it hard to see. “The drive seemed to take forever… But once we finally got through the fire, the relief was amazing,” says Louise.

After driving all night, the exhausted group set up camp near the Deh Cho bridge—220 kilometres from the Alberta border—to sleep for two hours before hitting the road again at 8:00 a.m. But 20 minutes into the second half of their journey, one of Louise’s worst nightmares came to life: The group realized that Sedze was not in any of their vehicles. She was missing.

The group sped back to their campsite, believing they may have accidentally left Sedze there. But there was no sign of her. They flagged down passersby, desperately asking if anyone had seen a small Shih Tzu, to no avail.

Though Louise tried to stay positive, deep down she feared the worst: either a wild animal had killed Sedze or she had drowned in the nearby Mackenzie River. After searching for 30 minutes, Louise and the others continued the journey south, heartbroken but still holding out hope for a miracle.

Later that evening, the group finally arrived in High Level. Louise called her daughter, Jilaine, who lives in Calgary, and broke the news. Ten minutes after they hung up, Jilaine called back with a shocking update. A man named Ryan Snyder had posted about a dog he found wandering out of the bush near the Deh Cho bridge on the Facebook group Yellowknife Lost/Found Pets. The dog looked exactly like Sedze!

Louise quickly got on the phone with Ryan and confirmed Sedze’s identity with a description of a faux pink flower attached to her collar. Sedze was alive and well. And as it turns out, Ryan had also evacuated to High Level: while speaking to each other on the phone, they discovered that they were standing on opposite sides of the same baseball field.

“It was the greatest feeling when he brought her over on her leash and she was sled-dogging it toward us,” she says. Today, Louise still marvels at their luck that Ryan found Sedze and reunited her with her family.

Three weeks later, on September 6, the order was lifted and the group returned to their homes in Yellowknife. “If my house had burned to the ground, I could have replaced it,” Louise says. “But you can’t replace your family.”

Next, check out these heartwarming dog stories that’ll make you smile.

While studying abroad in Australia in 2016, Ryann McIntire began experiencing severe joint pain, unstable blood-sugar levels, brain fog and other debilitating symptoms. It got so bad that the then 21-year-old flew home to Massachusetts early in search of answers.

After a friend suggested that she might have Lyme disease, McIntire asked her doctor for a blood test, which confirmed she had the antibodies in her system. That result, as well as her symptoms in the years prior, led McIntire’s doctor to conclude that she had been living with Lyme disease for more than a decade—most likely since an elementary-school field trip in the early 2000s near her home in Cape Cod, after which a nurse pulled a tick from her scalp.

Blacklegged ticks transmit the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease. The condition was first identified in the 1970s in Lyme, Connecticut—hence the name—about 240 kilometres southwest of McIntire’s fateful field trip. Symptoms include fatigue, fever, joint pain, headache and chills, and they can appear anywhere from three to 30 days after a bite. That makes diagnosis a challenge, as does the fact that the symptoms are common to multiple illnesses, says Janet Sperling, an entomologist and president of CanLyme, the Canadian Lyme Disease Foundation. The one symptom unique to Lyme disease, a bull’s-eye-shaped rash, doesn’t occur in all patients.

Lyme disease is diagnosed by a blood test that detects antibodies made by the body in response to the infection, and it can treated with antibiotics. But if it goes undiagnosed, like in McIntire’s case, it can affect the central nervous system, resulting in a hard-to-treat, chronic condition called neurologic Lyme disease, characterized by brain fog, pain and muscle weakness.

The good news is that a vaccine to prevent Lyme-disease infection is on the way. Moderna has two novel mRNA Lyme-disease vaccines in development. And Pfizer Inc. and French drugmaker Valneva SE have a vaccine currently in Phase III trials. It’s expected to be available to the public in the next few years.

While a vaccine for dogs has been around since the 1990s, the first human Lyme vaccine, LYMErix, was taken off the market by its manufacturer in 2002, after only four years. At the time, sales were low, partly because the market was small and partly because of unproven claims that the vaccine caused arthritis.

Since then, cases have risen. Ticks thrive in warm, humid environments, and their habitat is expanding thanks to climate change. They live in wooded areas, on the edge of forests, under tree canopies and in tall grasses. The tick—and Lyme disease—has been found in nearly every province. The Public Health Agency of Canada reported roughly 3,000 cases of Lyme in 2021, but experts believe the true number could be as much as 10 times higher.

Until a vaccine is widely available, your best defence against Lyme disease is to avoid getting bitten by a black-legged tick, says Sperling. “We’re not going to get rid of them,” she says. “So we have to learn to live with them.”

So how do you keep ticks at bay?

- Wear light-coloured clothing when hiking to make it easier to spot ticks. Wear clothing treated with the insecticide permethrin.

- Keep your skin covered by wearing long pants, socks and closed-toed shoes. Tuck your pants into your socks, and your shirt into your pants.

- Stick to the trails and avoid walking through high grasses.

- Spray yourself with a repellent that contains 30 percent DEET or 20 percent icaridin (also known as picaridin).

- Landscape your yard to make it inhospitable for ticks. Use tick tubes, which contain cotton treated with permethrin, to kill ticks that mice may carry into your yard.

- After spending time outdoors, check yourself for ticks, including your scalp, groin, the backs of your knees and behind your ears.

- As soon as you get home from a hike, put your clothes in the dryer on high heat for at least 15 minutes, even before washing them.

Next, read about 42 strange symptoms that can signal a serious disease.

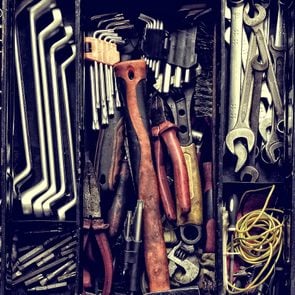

Simply stated, wheel bearings allow cars and trucks to run smoother and more efficiently by reducing friction and supporting vehicle weight. When they start to fail, you can usually tell.

Read on to learn the most common bad wheel bearing symptoms, based on my experience (50 years in the industry) and that of Joe Simes, a National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) certified and Toyota master technician. But first, a little background.

What are wheel bearings and what do they do?

On modern front- and four-wheel drive cars, wheel bearings are a set of permanently sealed, precisely machined steel ball or straight roller bearings. The balls, or rollers, are encased in a “cage” that supports the bearings, allowing them to rotate freely.

The cage and rollers are held together inside a hardened metal ring called a “race.” The seal keeps grease in and damaging water and debris out. Wheel bearings are installed inside, and secured to, the suspension, either by press fit, bolts or a snap-ring. Once mounted, the wheel bearing rides on the axle shaft, allowing the tire/wheel to spin effortlessly.

Note: Older cars with drum brakes and trailers use a set of two tapered roller bearings that face each other.

What are the first signs of wheel bearing failure?

According to Simes, a failing wheel bearing will likely produce a soft, faint vibration that’s felt before it’s heard. There may also be a vague rhythmic humming or droning sound that increases over time and with speed.

Do not ignore these warning signs. They’ll only get louder, and more serious symptoms may become noticeable.

What other symptoms indicate bad wheel bearings?

Unusual noises coming from the wheels

You’ll hear clicking, cracking, grinding, snapping, or whining noises coming from your wheels or tires. They’ll increase when accelerating or turning.

Poor handling

Steering feels unresponsive or sloppy when turning or braking, or at highway speeds.

Pulling to one side while driving or braking

A bad wheel bearing can cause a tire/wheel to move or glide unevenly or sluggishly. It can also cause your brakes to drag, pulling your vehicle to one side when you try to stop.

Shaking while driving

Unlike unbalanced tires, shaking caused by a bad wheel bearing should be obvious from the side of the car where the bearing is failing.

Uneven tire wear

Any loose or vibrating suspension part can cause tires to wear unevenly.

Anti-lock braking (ABS) dash comes light on

On many vehicles, the ABS sensor is built into the wheel bearing, or it’s externally mounted adjacent to the spinning part of the bearing where the sensor measures vehicle speed. Damaged from a wobbly wheel bearing, the sensor will send erratic readings to the vehicle’s computer, illuminating the ABS light.

Excess heat from the tires and wheels

Friction from a failing wheel bearing produces heat. After driving, without touching the tires or wheels, carefully walk around your vehicle and use a non-touch thermometer to measure if one is hotter than the others.

Why do wheel bearings fail?

Wheel bearings should last 135,000 to 160,000 kilometres. They can fail due to:

- Low tire pressure

- Hitting a pothole, bouncing off a curb or getting into an accident

- Driving on unbalanced tires or an out of alignment suspension

- Harsh climates

- Failed seals

- Oversized wheels and tires

- Under- or over-tightened a hub nut

Can you drive a car with bad wheel bearings?

Absolutely not. It’s crucial to get bad wheel bearings diagnosed and replaced ASAP. If not, you could lose a wheel or get in an accident.

How much does it cost to fix or replace bad wheel bearings?

The average cost to replace a sealed wheel hub bearing is $350 per wheel. However, depending on the make and model, shop labour rate, the cost of the bearing itself and any additional damage, the total could exceed $1,000.

Can I fix or replace wheel bearings myself?

It depends.

You can service or replace tapered wheel bearings yourself. Never reuse any wheel bearing that’s loose, worn, noisy or shows any signs of wear.

But sealed wheel bearings are non-serviceable and should never be repaired, only replaced. Even if a pro suggests repairing a bearing, don’t let them. Trying to reuse a damaged wheel bearing can result in an accident and severe injury.

Depending on the vehicle, you can save hundreds in labour replacing wheel bearings yourself. Most auto parts stores will lend you the specialty tools and equipment needed to replace a wheel bearing.

NOTE: Whether you DIY or your mechanic replaces the bearing, always install a new axle hub nut. Most hub nuts are prevailing torque fasteners, used on critical components (like securing axle shafts to hub bearings) where a loose nut could lead to disastrous consequences.

About the expert

Joe Simes is an ASE and Toyota master technician. After 20 years in the industry, Simes recently became a Pennsylvania Department of Education certified automotive technology instructor at North Montco Technical Career Center in Lansdale, Pennsylvania.

Next, check out these 10 must-try Canadian road trips.

We’d all love to roll out of bed to the sound of birds chirping and a few minutes of peaceful meditation, but responsibilities like children, pets, and work often make that challenge a dream. If you begin your day on the move, particularly with one type of popular alarm clock, new research says you might want to make a simple tweak to your routine…and possibly your phone settings.

A new study has found that your phone’s alarm clock function could potentially increase the risk of heart attack or stroke. Blood pressure naturally lowers during sleep and then peaks in the morning, a phenomenon called the “morning blood pressure surge.” A previous study by the American Heart Association found that several studies have linked an exaggerated morning blood pressure spike with cardiovascular problems, including heart attack and stroke. Several factors can impact that morning surge, including a shorter duration of sleep, age, general blood pressure status, stress, day of the week, season, and certain lifestyle choices like smoking and drinking.

The circumstances of your wakeup routine may also play a role. The University of Virginia has shared the results of research by Yeonsu Kim, a doctoral candidate at the UVA School of Nursing, who enlisted 32 participants for a two-day experiment using smartwatches and finger blood pressure cuffs to test the effects of waking up naturally versus using a smartphone alarm clock. The first night, participants woke up when their body naturally wanted to, and the second night they were awakened by the phone alarm after five hours of sleep.

What Kim found was “evidence of a link between short sleep duration, forced awakening and morning blood pressure surge,” according to the UVA School of Nursing’s news site. Forced awakening with the alarm clock had a 74% greater morning blood-pressure surge than waking up naturally. The 2.38 mmHg variance between the two groups was “a small difference,” Kim told Newsweek, but a UVA press release explains the impact this can potentially have on the heart: “When morning blood pressure surge is excessive, it can activate the sympathetic nervous system, which produces the ‘fight or flight’ response, which places stress on the heart, which pumps harder and stronger.”

The Best and Worst Diets for Your Cholesterol, Says UCLA Cardiologist

The fix

Unfortunately we don’t live in a world of weekends, making a disciplined wakeup time necessary for many of us. So here’s a possible solution, based on a 2019 study by researchers from the School of Integrated Technology in South Korea: Instead of using one of the harsh-sounding alarm sounds from your phone’s default settings, try some music or even make a wakeup playlist that starts the day on an optimistic foot. The study found that upbeat music was the most useful for getting moving with some energy, and melodies may help fight grogginess that can place added stress on the heart throughout the day.

Next, read about how sweetened drinks may increase heart risk by 50%.

When recent science graduates David Brown and Natasha Jean met in Fredericton, New Brunswick, the two became friends with a shared love of fitness and healthy eating. As chemists, they were aware of how bad for our bodies the preservatives in supermarket foods can be. Calcium propionate, for instance, prevents bread from going moudly by killing bacteria and yeast. But it has also been linked to an elevated risk of diabetes and obesity.

After reading a study about the capacity of mushroom fibre to preserve foods’ shelf life by acting as an antimicrobial agent, the two friends were intrigued. With a goal of developing a chemical-free preservative, they bought mushroom stems from farmers who would otherwise throw them out. Seven years later, in 2023, their company, Chinova Bioworks, has released mushroom-fibre extract that when added to foods, such as dairy products, increases shelf life with a taste that’s undetectable.

The company has even been testing the preservative with wineries in California and New Zealand. “It would replace the added sulfites that wine makers rely on right now for a long shelf life,” says Brown. Grapes naturally produce sulfite, so the extra is an overload that some people can’t tolerate.

It’s a win-win-win: for the climate (by reducing food-waste emissions), for our health and for the mushroom farmers who can sell their waste. “We’re trying to make an affordable product that companies will use,” says Brown. “We hope to make the food industry more sustainable.”

Next, read about why food made with artificial dyes should have a warning sticker.

When Stanford University student Ellen Xu, now 18, was a five-year-old in San Diego, California, she vividly recalls her parents rushing her little sister to the hospital. Three-year-old Kate had fallen acutely ill; she had a fever, reddened eyes, a rash and some swelling in her hands and tongue.

At first, the puzzled doctors thought she had influenza, but when her condition didn’t improve, the Xus returned to the emergency room, where a doctor by chance had prior experience with an acute inflammatory reaction in the blood vessels known as Kawasaki disease. Though rare, it’s the leading cause of acquired heart disease in babies and young children. Its cause and triggers remain somewhat mysterious.

The doctor knew how to treat it: He ordered a dose of intravenous immunoglobulin, and eventually Kate shook off the illness without suffering damage to her heart.

Xu remembers being curious about her sister’s dramatic condition and was amazed that the grown-ups couldn’t answer her questions about why it was so hard to detect. “In my mind, it was this mystery,” she says. “It was a puzzle I wanted to solve.”

A decade later, wanting to enter a high school science fair, she had an idea: “What if we had a doctor in our pocket?” So she created just that: Using AI, Xu designed an algorithm that uses visual data to diagnose Kawasaki disease based on five physical symptoms.

The technology works the same way as apps that can identify birds and plants with photos you’ve taken on your cellphone. Worried parents can upload a photo that they have taken of their child, and the technology will scan the image for symptoms of Kawasaki disease, which often have a strong visual element, such as a rash or a swollen tongue.

Xu’s invention has been implemented as a web app on the Kawasaki Disease Foundation’s website.

“The technology could also be developed for recognizing auto-immune and rheumatological diseases,” she says. “It means a lot to me. I want to use AI to help people live happier and healthier lives.”

Xu says that her sister Kate, now in her third year of high school with dreams of becoming an environmental engineer, is thriving.

Read more about mental health apps for mindfulness and much more.

In the early 17th century’s The Tempest, William Shakespeare had King Alonso ask the court jester, “How camest thou in this pickle?” You could say we’d all be in a pickle without the delightfully pungent and tangy food.

Today, you’ll run into pickles at every turn. Among the array of over-the-top offerings at fairs across Canada, including the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, the Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver and the ever-popular Calgary Stampede, are pickle-flavoured cotton candy, pickle fries, pickle pizza and pickle lemonade. And the most common food-delivery request in eight Canadian cities, according to a 2021 Uber Eats survey? “Extra pickles, please.”

Pickle mania is nothing new. Thousands of years ago, ancient Mesopotamians in modern-day Syria, Turkey and Iraq enjoyed cucumbers preserved in vinegar, brought from their native India. But the first mention of pickled vegetables made in salt brine comes 4,500 years before then, from an ancient Chinese manuscript more than 9,000 years old, writes Jan Davison in Pickles: A Global History. The staying power of preserved pickles made them perfect for the long, cold winters of European countries like Germany, Hungary and Poland, where they remain a staple.

Pickling involves soaking a food in a solution, usually vinegar or salted water (brine), to keep bacteria at bay—often with spices like garlic, dill, cloves and mustard seeds, which are not only flavourful but antimicrobial, too.

Around the world, many foods are pickled. Sauerkraut and kimchi are both fermented and pickled cabbage, while pickled herring is popular in Scandinavia. In India, you’ll find spicy pickled unripe mango. From lemons to pork hocks, okra to hard-boiled eggs, someone, somewhere, has pickled it.

Christopher Columbus typically packed pickled cucumbers (try saying that fast!) for long voyages, and the trip to the Americas in the late 15th century was no exception. Not only did pickles keep for months, but since cucumbers are an excellent source of vitamin C, they also helped prevent scurvy. Columbus acquired his pickles from Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian wheeler-dealer who sold supplies to seafarers, and, yes, for whom the United States of America was named. (Though Vespucci didn’t “discover” America any more than Columbus did, early map-makers incorrectly thought he did.)

Today, the two most common varieties of pickled cucumbers in North America are kosher pickles, brined with garlic, dill and spices—first brought to New York City by Jewish immigrants in the 19th century—and so-called bread-and-butter pickles, sweet thanks to brown sugar or syrup in the brine.

We have the founder of Heinz to thank for this popularity. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, Henry J. Heinz tempted fairgoers with a “free gift” of a pickle pin if they visited his booth. It worked, attracting massive crowds.

Heinz had the market cornered until the ’70s, when another American company, Vlasic, made ads featuring a stork who delivered pickles instead of babies.

Perhaps a daily pickle would do us all good, especially the fermented type, such as kimchi, since it is a source of probiotics and supports gut health.

So, in the manner of Shakespeare, take note of this idiom: Either you love pickles or you’re wrong.

Next, read all about how poutine became a classic Canadian favourite.

On a bright September day in the French Alps in 2022, John McAvoy was 38 kilometres into a gruelling ultramarathon through rugged mountain paths. Battling fatigue, he pushed his body and mind through the final stretch of the race. With the finish arch in the famous resort town of Chamonix just four kilometres away and the soaring cloud-topped peak of Mont Blanc hovering over him, McAvoy welled up with emotion. In that moment, he felt so free and alive.

It was quite the opposite from where his life had been a decade before. He had just been released from prison in the United Kingdom after serving a 10-year sentence for armed robbery. Now 40 years old, McAvoy has spent the last 10 years rebuilding his life from one of crime to one with purpose. After his release, he began speaking at schools and young offenders’ institutions. But it was on this day, while running the Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc, that he realized how impactful conquering this mountain run could be for inner-city kids. After all, sport had helped him rehabilitate and open up his world. It could do the same for others.

There were reasons why McAvoy had lost his way. His father died before he was born, and the closest male figure in his life was his stepfather, Billy Tobin, who, like his uncle Mick “the Nutter” McAvoy, was an infamous bank robber. Tobin came into John McAvoy’s life when he was eight years old, and eventually McAvoy started helping with the family’s criminal business. During his first stint in jail, at 19 years old, he spent 365 days in solitary confinement. “It’s like you are locked in a concrete coffin,” he says. By his early 20s, he was locked up for the second time.

McAvoy’s turning point came when his best friend, Aaron, died in a police chase following a heist gone wrong. He vowed to distance himself from bad influences and threw himself into training in the prison gym. A prison officer, Darren Davis, noticed McAvoy’s speed on the rowing machine and saw a young man who needed a chance. Under his coaching, Davis led McAvoy to best a string of British and world rowing records, all from jail.

When McAvoy was released in 2012, he dedicated himself to being a professional athlete—he’s now a Nike-sponsored endurance triathlete and an Ironman—and an advocate for prison reform and youth in sport.

With the help of Youth Beyond Borders, McAvoy started the Alpine Run Project, which recently led 12 disadvantaged British young people through their own Mont Blanc races. The participants, from refugees to young offenders and those who grew up in foster care, were matched with coaches, counsellors and physiotherapists. After a six-month training program, the youth travelled to the Alps to meet up with McAvoy for their race.

With former prison officer Davis (now a schoolteacher) still by his side, McAvoy says the pinnacle of this inaugural project for him was watching Yasmin Mahamud, a 20-year-old refugee from Syria who had escaped family abuse and homelessness, run through the finish arch (last, but not least) and into the arms of her new friends. It was a life-changing high for Mahamud, too—inspiring her to keep running, take up martial arts and go to university to study physiotherapy.

“It changed my point of view on life,” says Mahamud. Pushing herself to complete the race gave her a glimpse of her own potential through hard work and dedication. “I will always be thankful to John for giving me this opportunity and guidance.”

Next, check out these unique ways people are giving back around the world.