Is it okay to spoil my grandchildren?

Reader’s Digest Canada: We all know that spoiling kids is a bad idea, but is it okay for Grandma or Grandpa to engage in the odd act of overindulgence?

Mary Jane Sterne: A little overindulgence is part of the grandparent’s role, but you don’t want to do anything that directly contradicts the parents’ wishes—specific rules around food, for example. I always suggest that grandparents make themselves aware of their grandchild’s interests and do something special that supports that. When my granddaughter was younger, I would take her to her art class every week and then we would have a grilled cheese. It’s a nice memory, and something that helped her to engage in her passion.

What if her passion was playing Minecraft? I ask because a study from last year reported that grandparents are major culprits when it comes to excessive screen time.

Grandparents may be guilty of taking a slightly more relaxed attitude about that. But if you’re giving them 15 minutes of extra screen time so you can have a break, that’s not going to hurt anyone.

I’ve also read that grandparents are spending as much as seven times more money on grandchildren than they were a decade ago. Why is this?

Baby boomers are living longer, and we have more disposable income than our parents did. I have friends who make contributions to their grandchildren’s education funds and pay for summer camp—so it’s not like we’re just buying endless toys.

How else are things different for “grandboomers” than they were for their predecessors?

Parents aren’t necessarily seeking advice from the older generation as much. It used to be that when you had a baby, you’d turn to the grandparents for guidance on things like bottle temperature, sleeping and what your baby should be eating. Today, new parents get that information online. Being a grandparent today is often about zipping your lip.

On the other hand, you hear of grandparents who feel used by adult kids’ requests. Any advice on setting limits? Like, no, I can’t babysit for a third night this week.

Sure. That’s the whole idea behind “intentional grandparenting”—to communicate and set boundaries sooner rather than later. What you need is to get everyone on the same page. If you feel like you’re being taken advantage of, say something. Being a devoted grandparent is not the same as being a martyr.

Research shows that kids who are close to their grandparents have better mental-health outcomes. Why do you think that is?

With the parent/child relationship, the kids are worried about getting in trouble, and the parents worry about making mistakes. A grandparent, on the other hand, has an opportunity to provide a supportive, non-judgmental ear. For instance, I’ve heard of kids who have first come out as lesbian or gay to their grandparents.

Are grandparents better off because of their grandchildren?

Absolutely! One study showed engaged grandparents live five years longer than their counterparts. That makes sense—grandchildren can keep you active: I ski with my grandchildren; I bike with them. They can also give you a sense of purpose, which is something a lot of older people struggle with.

Check out the etiquette rules we should never have abandoned.

What I learned from Gordon Ramsay

Presenting anything you cook to others can be intimidating, especially when it’s Gordon Ramsay! However, for former U.S. Army Interrogator and MasterChef Season 10 runner-up, Sarah Faherty, working under intense pressure is nothing new. In fact, her military background is something she attributes to her success. As someone who thrives under pressure, Ramsay’s charisma certainly kept her on her toes, but also fuelled her to compete at her very best.

So what’s it like to be on MasterChef and have Gordon Ramsay standing over your shoulder as half mentor, half drill sergeant? Faherty recently sat down with Taste of Home to share her experience, and some of the biggest cooking lessons she learned from being on the show.

Pressure can be good

Ramsay is just as famous for his food as his fiery spirit in the kitchen. While Faherty confirmed that the yelling is certainly real, she learned quickly that having that added pressure in the kitchen is what helped push herself to the next level.

“People can see it [in Gordon]. He’s just so passionate. His intensity really does come from a good place. He wants you to perform at your best and he’s not afraid to push you past the point of comfort because that’s how we all grow. He loves to teach. He loves to help.”

These are the items you should never order at a restaurant.

Trust your instincts

One of the greatest changes Faherty has seen in herself since the show has been her confidence. One of her greatest takeaways from Ramsay was to trust her instincts in the kitchen. She recalled a specific example comparing the lamb she prepared on two occasions.

“Gordon has this insane talent where he can literally come over and touch whatever piece of protein is on your station and know exactly what temperature it’s going to be in the center after it’s rested. It’s very intimidating initially but it’s something that comes through experience and learning to trust yourself.

In the auditions, I used the temperature gauge on my lamb to make sure that it was good. However, in the finale, I didn’t use a temperature gauge at all. I touched it. And I just felt like I was very confident in what the temperature was going to be inside.”

Make sure to avoid these cooking mistakes that ruin your food.

Know your limits

It wasn’t always easy for Faherty on MasterChef—viewers will recall her was nearly eliminated during cake week when her ambitious cake didn’t get out of the oven in time to properly cool before decorating. Luckily, this mishap wasn’t enough to send Faherty home, and she was able to learn from this mistake to carry her on through the competition.

“Everything is not always going to turn out perfect. But that’s kind of OK. It’s part of the learning process. The cool thing in the cake week situation is that I learned from that experience. Choosing that cake was a terrible idea. Way too much work. I learned to not bite off more than you can chew and then make sure that you’re always properly gauging the competition.”

Believe in yourself

Faherty explains that she feels a lot of people struggle with impostor syndrome, including herself. It’s this constant question of, “am I good enough” or “am I as qualified as this person” that holds people back from pursuing their dreams.

“If you have a passion for something, then you deserve to be there. Don’t let any sort of impostor syndrome keep you from doing what you love. Instead of asking, ‘why me?’ say, ‘why not me?’ I think that is the biggest thing that I learned.”

Tell a story

During her time overseas in the military, she often used food to take a piece of home with her wherever she went. For Faherty, food has always been about the people, the culture and the stories that surround it.

“I don’t think being on MasterChef changed my food philosophy. I think it has just made me dive a little bit deeper into it. It especially brought out more of the aspect of telling a whole story when it comes to food and wine.”

Keep up with Sarah Faherty (@sarah_faherty) and her upcoming podcast (@everydayfoodandwine) by following her on Instagram!

These clever kitchen hacks will change how you cook for the better!

Surviving a wolf attack

Russ Fee was asleep inside his tent last summer when a series of screams jolted him awake. Throwing on his shoes and grabbing a lantern his wife had handed him, he ran out to investigate, expecting to find two scared parents whose kids had wandered off. Fee and his wife were travelling through Canada’s Banff National Park to enjoy its stunning beauty and awesome wildlife. It was the latter he now encountered. Although it was dark, Fee could discern a neighbouring tent in shambles. Backing out was a wolf, dragging something in his teeth. That thing was a man.

Moments earlier, Elisa and Matt Rispoli, from New Jersey, were asleep with their two young children when the wolf tore into their tent. “It was like something out of a horror movie,” Elisa posted on Facebook. For three minutes, “Matt threw his body in front of me and the boys and fought the wolf.” At one point, Matt got the upper hand, pinning the wolf to the ground. But the wolf clamped its jaw onto Matt’s arm, set its powerful legs, and began tugging Matt outside “while I was pulling on his legs trying to get him back,” Elisa wrote.

It was then that Russ Fee entered the picture. He ran at the beast, kicking it in the hip “like I was kicking in a door,” he told ABC New York. The wolf dropped Matt and emerged from the tent. Wolves are large, Fee told the radio show Calgary Eyeopener. “I felt like I had punched someone that was way out of my weight class.”

Before the wolf could turn its ire on Fee, Matt, his arms bloodied, flew out of the tent to resume the battle. The men pelted the wolf with rocks, forcing it back, then the Fees and the Rispolis fled to the shelter of the Fees’ minivan. An ambulance was called, and Matt was taken to a local hospital suffering puncture wounds and lacerations. He has fully recovered. Park officials closed down the campground until they tracked down the wolf and euthanized it. Canada is home to 60,000 wolves, according to the International Wolf Center. Still, they wrote, on their website, attacks are so rare that “a person in wolf country has a greater chance of being killed by a dog, lightning, a bee sting, or a car collision with a deer than being injured by a wolf.”

As for Fee, whom Elisa dubbed their guardian angel, he does admit to a fleeting, if less-than-heroic, thought during the heat of battle. The moment the wolf locked eyes with him, Fee says, “I immediately regretted kicking it.”

Next, find out how a Facebook thread saved two friends who were gravely injured in the Bali jungle.

Mind Over Meds

“Here they are,” John Kelley said, taking a paper bag off his desk and pulling out a big amber pill bottle. Inside were the capsules we’d designed: a magical concoction to treat my chronic writer’s block and the panic attacks and insomnia that always come along with it.

I’ve known Kelley since we were undergrads at Harvard in the early 1980s. Now he’s a psychology professor at Endicott College in Massachusetts and the deputy director of PiPS, Harvard’s Program in Placebo Studies & Therapeutic Encounter. Launched in 2011, it’s the first program in the world devoted to the interdisciplinary study of the placebo effect.

The term placebo refers to a dummy pill passed off as a genuine pharmaceutical or, more broadly, any sham treatment presented as a real one. By definition, a placebo is a deception, a lie. But doctors have been handing them out for centuries, and patients have been getting better—whether through the power of belief or suggestion, no one’s exactly sure. Even today, when the use of placebos is considered unethical by many medical professionals, a 2008 survey of 679 American doctors showed that about half of them prescribe medications such as vitamins and over-the-counter painkillers primarily for their placebo value.

Interestingly, the PiPS researchers have discovered that placebos seem to work well even when a practitioner doesn’t try to trick a patient. These are called open-label placebos—fakes explicitly prescribed as such.

So in 2015, I had turned to my old friend for help with my writer’s block. “I think we can design a pill for that,” he’d told me initially. “We’ll fine-tune it for maximum effectiveness, colour, shape, size, dosage and time before working. What colour do you associate with writing well?”

I closed my eyes. “Gold.”

“I’m not sure the pharmacist can do metallic. It may have to be yellow.”

Over the next few weeks, we discussed my treatment in greater detail. Kelley suggested capsules rather than pills, as they would look more scientific and therefore have a stronger effect. He also made them short acting: he believed a two-hour time limit would cut down on my tendency to procrastinate. We composed a set of instructions that covered not only how to take them but also what they were going to do. Finally, we ordered 100 capsules, which cost a hefty $405, though they contained nothing but cellulose. Placebos are not covered by insurance.

Kelley reassured me: “The price increases the sense of value. It will make them work better.”

I called the pharmacy to pay with my credit card. After the transaction, the pharmacist said to me, “I’m supposed to counsel customers on the correct way to take their medications, but honestly, I don’t know what to tell you about these.”

“My guess is that I can’t overdose.”

“That’s true.”

“But do you think there’s a chance I could get addicted?”

“Ah, well, now that’s a really interesting question.”

We laughed, but I felt uneasy. Open label had started to feel like one of those postmodern magic shows in which the magician explains the illusion even as they perform the trick—except there was no magician. Everyone was making it up as they went along.

One of the key elements of the placebo effect is the way our expectations shape our experience. As Kelley handed over the pills, he wanted to heighten my expectancy, as psychologists call it, as much as possible. He showed me the official-looking stuff that came with the yellow capsules: the pill bottle, the label, the prescription, the receipt from the pharmacy and the instruction sheet we’d written together, which he read to me out loud. Then he asked me whether I had any questions.

Suddenly we were in the midst of an earnest conversation about my fear of failure as a writer. There was something soothing about hearing Kelley respond, about his gentle manner. As it turns out, that’s another key element of the placebo effect: an empathetic caregiver. The healing force, or whatever you want to call it, passes into you from the placebo, but it helps if it starts with someone who wants you to get better.

Back home, I sat down at the dining room table with a glass of water and a notebook. Take two capsules with water 10 minutes before writing, said the label. Below that: placebo, no refills. I unfolded the directions: “This placebo has been designed especially for you, to help you write with greater freedom and more spontaneous and natural feeling. It is meant to help eliminate the anxiety and self-doubt that can sometimes act as a drag on your creative self-expression. Positive expectations are helpful but not essential: it is natural to have doubts. Nevertheless, it is important to take the capsules faithfully and as directed because previous studies have shown that adherence to the treatment regimen increases placebo effects.”

I swallowed two capsules and, per the instructions, closed my eyes and tried to imagine the pills doing what I wanted them to do. But still, I worried that my anxieties about their not working might prevent them from working.

Over the next few days, I felt my anxiety level soar while at work and when filling out the self-report sheets. “On a scale of zero to 10, where zero is no anxiety and 10 is the worst anxiety you have ever experienced, please rate how you felt during the session today,” one section read. I was giving myself eights out of a misplaced sense of restraint, though I wanted to give 10s.

Then, one night in bed, my eyes opened. My heart was pounding. The clock said 3 a.m. I got up and sat in an armchair and, since my pill bottle was there on the desk, took two capsules, just to calm down. They made me feel a little better, but I didn’t actually get to writing. In the morning, I emailed Kelley, who wrote back saying that, like any medication, the placebo might take a couple of weeks to build up to a therapeutic dose.

Ted Kaptchuk, Kelley’s boss and the founder and director of PiPS, has travelled an eccentric path. He became embroiled in radical politics in the 1960s and studied Chinese medicine in Macau. After returning to the United States, he practised acupuncture in Cambridge, Mass., and ran a pain clinic before being hired at Harvard Medical School. But he’s not a doctor, and the degree he earned in Macau isn’t recognized here.

Kaptchuk’s outsider status has given him an unusual amount of intellectual freedom. In the intensely specialized world of academic medicine, he routinely crosses the lines between clinical research, medical history, anthropology and bioethics. “They originally hired me at Harvard to do research in Chinese medicine,” he told me. His interests shifted when he tried to reconcile his own successes as an acupuncturist with his colleagues’ complaints about the lack of hard scientific evidence. “At some point in my research, I asked myself, if the medical community assumes that Chinese medicine is just a placebo, why don’t we examine this phenomenon more deeply?”

Some studies have found that when acupuncture is performed with retractable needles or lasers, or when the pricks are made in the wrong spots, the treatment still works. By conventional standards, this would make acupuncture a sham. If a drug doesn’t outperform a placebo, it’s considered ineffective. But in the acupuncture studies, Kaptchuk was struck by the fact that patients in the sham treatment group were actually getting better. He points out that the same is true of many pharmaceuticals. In experiments with post-operative patients, for example, prescription pain medications lost up to half their effectiveness when the patient did not know they had just been given a painkiller. A study of the migraine drug rizatriptan found no statistical difference between a placebo labelled rizatriptan and actual rizatriptan labelled placebo.

What Kaptchuk found was something akin to a blank spot on the map. “In medical research, everyone is always asking, ‘Does it work better than a placebo?’ So I asked the obvious question that nobody was asking: ‘What is a placebo?’ And I realized that nobody ever talked about that.”

Working with Kelley and other colleagues, he’s found that the placebo effect is not a single phenomenon but rather a group of interrelated mechanisms. It’s triggered not just by fake drugs but by the symbols and rituals of health care itself—everything from the prick of an injection to the sight of a person in a lab coat.

And the effects aren’t just imaginary, as was once assumed. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, which maps brain activity by detecting small changes in blood flow, shows that placebos, like real pharmaceuticals, actually trigger neurochemicals such as endorphins and dopamine and activate areas of the brain associated with analgesia and other forms of symptomatic relief.

“Nobody would believe my research without the neuroscience,” Kaptchuk told me. “People ask, ‘How does a placebo work?’ I want to say by rituals and symbols, but they say, ‘No, how does it really work?’ and I say, ‘Oh, you know, dopamine,’ and then they feel better.”

To gain a greater understanding of the physiology, PiPS has begun sponsoring research into the genetics of placebo response. After meeting with Kaptchuk, I visited the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to see Kathryn Tayo Hall, a geneticist. She studies the gene for catechol-O-methyltransferase (also called COMT), an enzyme that metabolizes dopamine. In one study, Hall found that the type of COMT enzyme patients possessed seemed to determine whether a placebo would work for them.

Is the COMT gene “the placebo gene”? Hall was quick to put her findings into context. “The expectation is that the placebo effect is a knot involving many genes and biosocial factors,” she told me, not just COMT.

There’s another layer: worriers—people who have higher dopamine levels—can exhibit greater levels of attention and memory but also greater levels of anxiety, and they deal poorly with stress. Warriors—people with lower dopamine levels—can show lesser levels of attention and memory under normal conditions, but their abilities increase under stress. The placebo component thus fits into the worrier/warrior personality types as one might expect: worriers tend to be more sensitive to placebos; warriors tend to be less sensitive.

I told Hall, a little sheepishly, about my one-man placebo trial, not sure how she would react. “Brilliant,” she said, and showed me a box of homeopathic pills she used to take to help with pain in her arm from an old injury. “My placebo. The only thing that helped.”

What might the future of placebos look like? Kaptchuk imagines doctors one day prescribing open-labels to their patients as a way of treating certain symptoms without the costs and side effects that can come with real pharmaceuticals. Other researchers are focusing on placebos’ ability to help patients with hard-to-treat symptoms such as nausea and chronic pain. Still others talk about making conventional medical treatments even more effective by using the symbols and rituals of health care (such as getting an injection from someone in a white lab coat) to add a placebo effect.

Hall would like to see placebo research lead to more individualized medicine; she posits that isolating a genetic marker could allow doctors to tailor treatment to a patient’s individual level of placebo sensitivity. Citing the research showing that an empathetic caregiver is key, Kelley also hopes to refocus our attention on the relationship between patient and caregiver, reminding us all of the healing power of kindness and compassion.

I’d been taking my writing capsules for two weeks when I began to feel an effect. My sentences were awkward and slow, and I disliked them as much as ever, but I didn’t throw them out: I didn’t want to admit to that in the self-reports I was keeping, sheets full of notes such as “Bit finger instead of erasing.” When the urge to delete my work became overwhelming, I would swallow a couple of extra capsules (I was way, way over my dosage—had in fact reached Valley of the Dolls levels of excess). “I don’t have to believe in you,” I told them, “because you’re going to work anyway.”

One night, my 12-year-old daughter was having trouble sleeping. She was upset about a situation with the other kids in school; we were talking about it, trying to figure out how best to help, but in the meantime, she needed to get some rest.

“Would you like a placebo?” I asked.

She seemed interested. “Like the ones you take?”

I got my bottle and did what John Kelley had done for me in his office, explaining the scientific evidence and showing her the impressive label. “Placebos help many people. It helped me, and it will help you.” She took two of the shiny yellow capsules and within minutes was deeply asleep.

Standing in the doorway, I shook a couple more capsules into the palm of my hand. I popped them into my mouth and went back to work.

Next, find out the real reason why women’s pain is often dismissed.

Published Feb. 14, 2020

Reader’s Digest Canada: The new coronavirus outbreak has put germs top of mind. How can we avoid exposing ourselves?

Jason Tetro: People want to hear there’s something they can do to take extra precaution right now, but the way you can protect yourself from coronavirus is the same way you protect yourself from regular flu bugs and other pathogens: Wash your hands frequently and avoid contact with surfaces that are touched by a lot of people, such as door knobs, handles and buttons.

In your own home, you can clean and disinfect surfaces touched often, which are generally in the bathroom and the kitchen. Understandably, there is a lot of attention being paid to coronavirus—technically called COVID-19—at the moment, but the the regular flu still poses a comparable threat to Canadians.

How is the coronavirus different from the regular flu?

Coronaviruses are a category of respiratory viruses that infect a number of species including humans. They come in various strains or strengths—some as harmless as the common cold, a couple that can cause a strong pneumonia and then some that are real killers. In 2003, SARS was the first coronavirus outbreak that caused a serious public health threat. Then there was MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) in 2012. And now we have COVID-19.

Why have these more dangerous coronavirus strains only cropped up in the last 20 years? Humans have been getting colds for thousands of years.

That’s something we don’t know. We do know that these viruses are zoonotic, meaning they’re transmitted from animals to humans. Initially, the theory was that transmission of COVID-19 required close body contact—like kissing. Now we believe it can be caught by droplets from a few feet away. It’s possible that it can travel through air vents—we’ll know more about that when we see who gets sick on board the quarantined cruise ships.

At this point there’s no reason to think this virus is like Ebola or measles, which can stay in the air for hours even when the person who shed it is long gone.

A lot of people are wearing face masks. Is that a smart precaution?

I don’t think it’s necessary—not unless there’s an uncontrolled spread of the virus in your community. Also, for any kind of virus, face masks don’t provide any protection that you can’t get from a scarf and making sure people around you sneeze into their sleeves.

What about hand sanitizer? Should everyone be stocking up?

Hand sanitizer is good if you don’t have access to a sink, but otherwise, soap and water is the best option. One tip is that a lot of people don’t wash their hands for long enough. We say you should scrub for about 20 seconds, or the length of singing “Happy Birthday” twice. That’s going to get rid of any pathogens, which are the germs that get us sick.

As opposed to the germs that don’t?

Pathogens only make up about one-tenth of one per cent of germs or bacteria that humans are exposed to. The rest are either benign or actually helpful.

How can germs be helpful?

Our skin has a barrier made up of various microbes that protect us from irritation and infection. That’s not something you want to disrupt by excessive cleaning. There’s also gut bacteria that helps with our digestion.

Overall, exposure to a diverse array of germs, particularly at a young age, is beneficial for developing a strong immune system and good health in general. An allergy, for instance, is the body mistaking a friendly germ for a dangerous one because it’s not familiar with it. More kids have allergies today than ever because they’re raised in urban environments where there isn’t a lot of germ diversity.

So parents should let their kids spend more time rolling around in the dirt?

Sure! I always say let your kids eat dirt unless it’s in the dog park.

Find out more diseases you can prevent simply by washing your hands.

Senior moment

When Tom Gibson retired from his job as a business consultant, he was looking forward to a little downtime. But the 65-year-old soon realized that, for him, there was such a thing as too much relaxation. “I found out through retirement that I was not the retiring type,” he says. “I wanted to—and actually needed to—stay busy.”

Initially, he thought he’d stave off boredom by volunteering at Community Innovation Lab, an Oshawa, Ont., not-for-profit that supports budding entrepreneurs. Instead, he ended up getting support to build a new family business thanks to the lab’s latest pilot project: the Seniorpreneur Program 4 Innovation, Creativity and Entrepreneurship (SPICE). Founded by community organizer Pramilla Ramdahani last year, it helps the growing number of people aged 55 or older who want to start their own businesses.

According to a 2015 Statistics Canada report, one in five Canadians aged 65 and older reported working at some point during the year. For some, this is a matter of financial necessity—we’re living longer, which means our retirement savings and pensions have to go much further. Other seniors, like Gibson, are continuing to work or opting to re-enter the workforce because they want mental and social stimulation. “SPICE provides an opportunity for them to use the wisdom, knowledge and passions they have been sitting on,” Ramdahani says.

In its first year, SPICE hosted three “boot camps” for cohorts of 20 seniors each. The groups met to build a business plan and connect with professionals, like accountants and marketers, who had small-business expertise.

Some of the seniors who participated came with only an idea for professional services, such as financial planning or workplace wellness, or for products, like all-natural undergarments or stylish cycling gear. Others, like Gibson, were further along in the process. He and his sons were already working on a company, Havlar, that sells mobile safes in which to store valuables, like cellphones and wallets. (The idea came from Gibson’s son Daryl whose hockey bag was stolen while he was on the ice.)

“I had a very solid business plan to work from and make better,” Gibson says. “But you also got feedback from other people in the class on how you could do things differently or think about things that maybe you hadn’t. And the networking part of it was also helpful.”

Ramdahani is currently trying to secure funding to offer more boot camps in the future. And she’s hoping SPICE can expand beyond Durham Region. In the meantime, though, Community Innovation Lab is continuing to offer support to entrepreneurial seniors, whether it’s through one-off workshops or even just by offering a place to hold meetings.

Gibson’s Havlar has entered its next phase: crowdfunding its manufacturing process so its safes can start being sold later this year. He’s pleased at what he and his sons have been able to do so far—and hopeful about what comes next. “How sweet was it that I could actually commit my time and energy to build something with my family that is hopefully enduring? Maybe even create a legacy? I didn’t want to miss an opportunity, however late in life, to make this kind of contribution.”

Next, find out how one Toronto woman is helping others pull themselves out of poverty.

It’s a Small World laughter all: Disney puns

A man went to see the doctor and exclaimed, “Doctor, I need your help. Some mornings I wake up thinking I’m Mickey Mouse, and other times I think I’m Donald Duck!”

The doctor nodded. “I see. And how long have you been having these Disney spells?”

If you watch The Lion King closely, you’ll notice lots of Simba-lism!

Q: What happened the first time Mickey and Minnie saw each other?

A: It was glove at first sight!

Q: What does the rapper Lil Jon say when he visits Disneyland?

A: Turn down for Walt!

Q: What did Captain Hook’s sidekick say to Adele?

A: Hello, it’s Smee!

Classic Disney jokes

Q: Why is Peter Pan flying all the time?

A: He Neverlands!

Q: What does Daisy Duck say when she buys lipstick?

A: Put it on my bill!

Q: Where does Captain Hook go to get his hook replaced?

A: The second-hand store!

Q: Why did Goofy wear two pairs of pants when he played golf?

A: He heard he might get a hole in one!

Q: Why did Mickey Mouse become an astronaut?

A: So he could visit Pluto!

Q: Why is Quasimodo great at solving crimes?

A: He always has a hunch!

Discover these hidden gems for grown-ups at Disney parks.

Marvel-ous Disney jokes

Q: Does the God of Thunder like ice cream?

A: Sure, but he prefers Thor-bet.

Q: How does Scarlet Witch channel her magic?

A: With a magic Wanda!

I just had an encounter with the God of Mischief. It was Loki terrifying!

Q: Who is Thor’s favourite rapper?

A: MC Hammer!

Some Forced humour: Star Wars Disney jokes

Q: What do you call a droid that likes taking the scenic route?

A: R2-Detour!

Q: What does The Child from The Mandalorian write in his Valentine’s cards?

A: Baby Yoda one for me!

Q: Is BB hungry?

A: No, BB-8!

Q: Which program do Jedi use to open PDF files?

A: Adobe Wan Kenobi!

Everyone should know these inspiring Star Wars quotes by heart!

Disney jokes fit for a princess

Q: Why is Cinderella so bad at soccer?

A: Because she’s always running away from the ball—not to mention, she has a pumpkin for a coach!

Q: Which Disney princess would make the best judge?

A: Snow White, because she’s the fairest of them all!

Q: Why shouldn’t you give Elsa a balloon?

A: Because she’ll let it go!

Q: Why is Gaston the most peaceful Disney villain?

A: Because he won the No-Belle Prize.

Q: What did Snow White say when her photos weren’t ready yet?

A: Someday my prints will come!

Q: Which princess makes the best corny Disney jokes?

A: Ra-puns-el.

If you’re a true Disney aficionado, see if you know the things never allowed in Disney movies.

When you consider that hackers attack every 39 seconds, according to a 2017 study from the University of Maryland, you start to grasp just how very real the danger is. Yet, “most people don’t think about security until it’s too late,” Guemmy Kim, lead of account security initiatives at Google tells Reader’s Digest. “The horror stories exist.”

Take for example this story of Laura, that Kim shares:

Laura was at work when she received a text alert from her bank confirming a $700 transfer request.

She immediately panicked because she hadn’t made the request. When she tried to log into her bank account to cancel the transfer, her password was rejected. She tried the “reset my password” option but found that she couldn’t log into her email to access the reset link from her bank.

That’s when Laura knew she’d been hacked—and it was because she’d used the same password on both accounts, and maybe not the most secure one, at that—her pet’s name.

Though Laura was able to cancel the transfer with a phone call to the bank, the email hack was trickier to fix. She ended up being locked out of her account for days. The hackers also had gotten into her online shopping account using the same password and ordered $500 in gift cards, which were sent to a different email address.

All told, it was about a week before things were back to normal with her accounts. Even after Laura regained access, she was haunted by what the hackers could’ve accessed through her email account. She spent many sleepless nights thinking about the social security number listed on tax document attachments and her home address that appeared in numerous emails.

This frustrating and time-consuming hacking horror story is actually not uncommon for people to find themselves in.”

You’ll also want to learn these secrets to steal from people who never get hacked.

The problem

Now that many of us do our banking online, our online accounts are often connected to your email accounts. That means if a hacker gets control of your email, they can get control of other things as well.

If a hacker gets into your email you could be accidentally giving them the ability to reset your passwords on other sites with disastrous results. “The hacker will go to your Amazon account or your banking account and then they’ll just say, ‘Oh, I forgot my password.’ Then that service will just be, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll just send you a reset link to your email.'” Now that they have access to your email, it’s very easy for them to go into the other site and change it the password, Kim warns. Then that locks you out of the account. “Then they go in, steal your money and order things and packages to their own home.”

One easy way hackers gain access to your accounts is when you reuse the same password and username on a number of sites, Kim shares. If one of those sites is compromised, as in the Yahoo customer security data breach when 3 billion accounts were compromised, for instance, then hackers might try the same username and password on other sites to see if it works. Knowing which password mistakes to avoid is also helpful.

What to do

While having secure, unique passwords is important, Kim suggests going to g.co/securitycheckup to make certain your account is as secure as you think it is. This is Google’s very high-level wizard that will walk you though things like adding a security number to your account or updating your password. You’ll also want to avoid using these 25 worst possible passwords.

As temperatures drop and winter leaves people craving a quick and comfy supplemental source of warmth, many consider pulling out a trusty space heater or investing in a new one.

Before you plug one in, know this: Heating is the second-leading cause of house fires (behind cooking), according to the National Safety Council, and in most cases, those fires involve space heaters. Though they look small, they require significant wattage and produce enough heat to require smart planning and precaution when using.

Always skip power strips

It’s rule No. 1: Don’t plug a space heater into a power strip, no matter how many hair straighteners, phone chargers, speakers, computers or gadgets may be vying for electricity. Space heaters must be plugged directly into a wall outlet, which can handle a higher wattage, and should be the only item plugged into that wall outlet. The Electrical Safety Board says space heaters can overheat a power strip, as well as an extension cord, and potentially cause a fire.

Locate space heaters away from hazards

Make sure the space heater is placed on non-flammable tile or hardwood flooring—not on the carpet or a rug. Keep heaters at least three feet away from bedding, clothing, paper or books and drapes, too. Don’t locate them in high traffic areas, or anyplace they might be a tripping hazard.

Use only with supervision

Only use a space heater when someone is in the room, and keep children and pets a safe distance away. Turn them off when you leave the room, and don’t run them when you’re asleep, either. (Find out the real risks presented by some of the most common household safety hazards.)

Check alarms and inspect cords

Make sure all of your smoke alarms are installed and working. Carefully check space heater cords for frays, cracks or breaks, and look for loose or broken connections, too. Keep the area around the space heater dry and free of moisture that may damage its components.

Shop for space heaters wisely

The American Red Cross advises choosing a space heater that automatically shuts off if accidentally tipped over. Some also shut off if they may be overheating.

Now, learn about the most common causes of house fires in Canada.

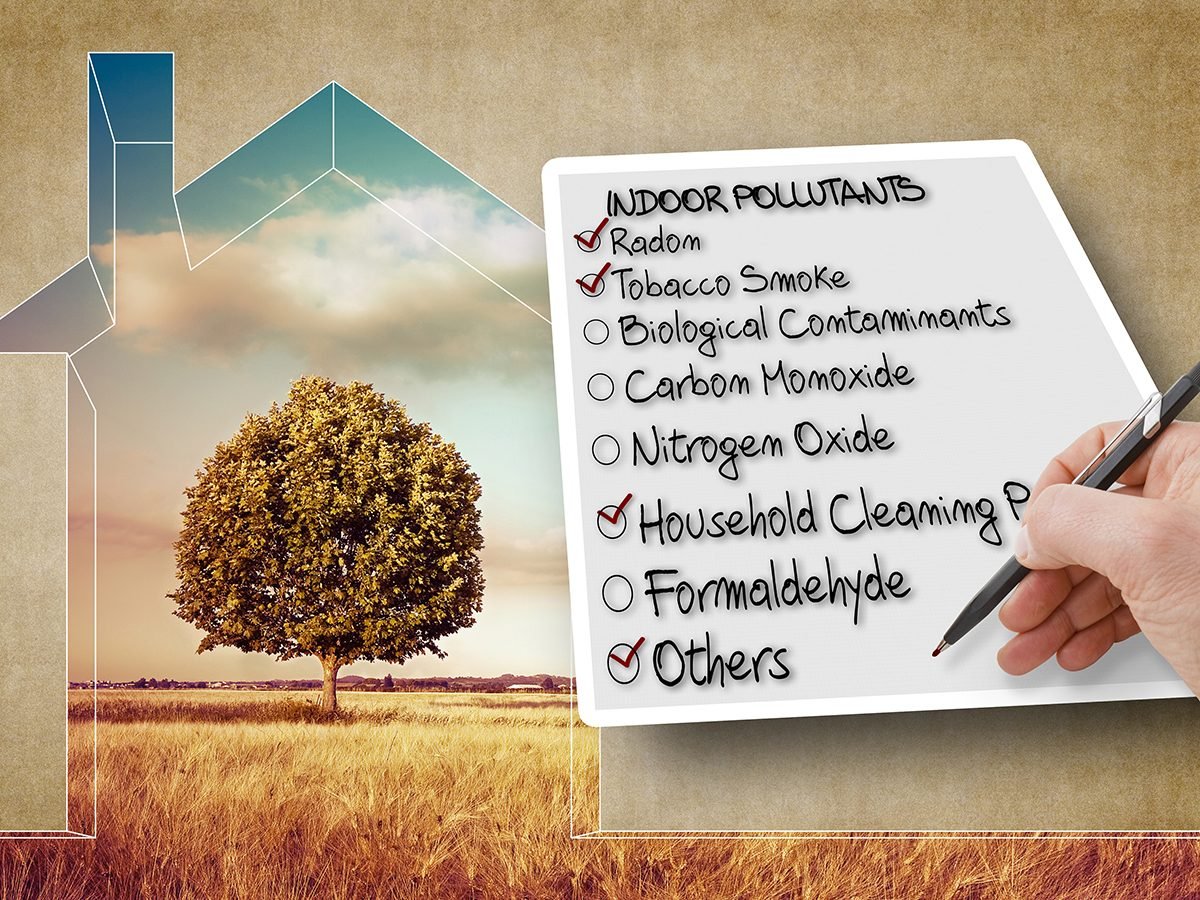

Here are four reasons you should do a home air quality test:

Find Allergy and Asthma Triggers

A home air quality test will determine if your home’s air has mould and mildew, which can cause breathing issues, along with skin irritation. The test can also tell you the level of dust and dander, which can trigger allergic reactions in some people.

Discover Carbon Monoxide Levels

If your home is sealed up so tight there isn’t enough intake air for natural-gas powered appliances, you could be inhaling carbon monoxide without even knowing it. The odourless gas can cause nausea, headaches, dizziness and even death. A home air quality test will tell you if the level in your home is too high. Find out exactly how dangerous these home safety hazards are.

Learn Radon and Asbestos Levels

Radon is a naturally occurring gas that can be in your home without you knowing it’s there. Radon is the number one cause of lung cancer in non-smokers, according to the EPA. (Learn how to spot the telltale signs of lung cancer.)

Asbestos, a group of naturally occurring minerals that are resistant to heat and corrosion, is recognized as a health hazard and its use is now regulated by government agencies. When people inhale or ingest microscopic asbestos fibres, it can lead to serious health problems.

Lower Energy Costs

A home air quality test can also bring to light problems with your HVAC system or if you have blocked air vents. By discovering these issues and fixing them, you’ll improve your home’s energy efficiency and in turn, lower your energy bill.

You can do a home air quality test yourself. Kits are available for about $300 on Amazon. You can also hire a professional to do a home air quality test. The cost is generally around $500, depending on the size of your home and the type of analysis you’re looking for.

Find out more ways your home could be making you sick.