As I discovered while researching my hometown, in the 1800s, Mimico, Ontario, was originally known by the First Nations People as Omimeca, meaning “the resting place of the wild pigeons.” The passenger or wild pigeon is now extinct, but its memory lives on in the name Mimico.

Situated to the west of Toronto, Mimico began to develop in the 1890s below Lakeshore Boulevard, where many of Toronto’s wealthiest families built their summer homes. A few of these homes still exist today, but most were lost to further development after the Second World War.

The town truly began to grow as a year-round community in 1906, when the Grand Trunk Railway opened its Mimico Yards. The need for nearby housing, as more railway workers and their families arrived, led to a building boom. As the yards took root, so did the community.

Mimico was incorporated in 1917 and retained its town status until 1967, when it was amalgamated with the borough of Etobicoke. In 2001, it became a community within Toronto.

Our family of three moved to Canada from the United States in 1925, and Dad built a home on the northern edge of Mimico. Over the next 14 years, seven more children were born into our family, and we all attended George R. Gauld Junior School and Mimico High School. We also attended church in town, had paper routes and other jobs, and brought home our respective boyfriends and girlfriends to meet our parents. In short, we kids all grew up there and what a wonderful place and time it was.

One fun memory I have is our annual summer trip as a family to Sunnyside Amusement Park on Lakeshore Road, which was essentially a waterfront playground offering rides, games, swimming and much more. For decades, it was a tremendous attraction for locals and visitors alike. The amusement park met its end with the construction of the Gardiner Expressway in the mid-1950s, but it is not forgotten.

Once all of us kids were grown up, Mother sold the family home in 1958 and purchased a large house on High Park Boulevard that had once belonged to a former mayor of Toronto. Our old house was torn down and a duplex built in its place. I was left with nothing but fond memories of our old community.

Now that you know the story of Mimico, Ontario, find out what it was like growing up in an Eaton’s catalogue mail-order house.

In 1873, St. Stephen, New Brunswick, was a bustling destination. Located just over the border from Calais, Maine, and a stone’s throw from the Bay of Fundy, the town was dominated by the lumber and shipbuilding trades. Brothers James and Gilbert Ganong saw local industries booming and decided the time was ripe to establish a new general store and expand into an emerging market: Chocolates and confectionery. Little did they realize their humble enterprise would become Canada’s longest-operating family-run chocolate company—and put St. Stephen on the map. In fact, the destination has become so synonymous with chocolate that in 2000, it was officially recognized as “Canada’s Chocolate Town.”

Ganong’s Claims to Fame

Innovation has been key to Ganong‘s 150-year history. Take the company’s Pal-o-Mine bar, for instance. The delicious mix of chocolate, fudge and peanuts debuted in 1920 and is now one of the oldest continuously-produced candy bars in North America. Local legend has it that second-generation candy-maker Arthur Ganong wanted to bring chocolate on his fishing trips, but needed something that wouldn’t melt in his wool trousers. (He was famous for eating two to three pounds of chocolate a day and certainly wouldn’t let a little fishing stand in his way.) His invention—a fully-wrapped chocolate bar (most chocolate at the time being sold as tablets or in boxes)—paved the way for the chocolate bar packaging (and Pal-o-Mine bar) we know today. Oh, and the price of that first run of Pal-o-Mine bars? A mere five-cents each.

This wasn’t the only time that Ganong was responsible for a memorable “first”. The company also introduced Canada to the heart-shaped chocolate box in the 1930s, first as a Christmas treat and then later as a Valentine’s Day product.

While many of Ganong’s products have been around for more than 100 years, the company continues to experiment with new flavours. Their New Brunswick-inspired collection of truffles contains some classic Canadian ingredients, like molasses, blueberry and maple, along with one you might not expect: Dulse. This tasty seaweed found along the shores of New Brunswick has a deep saltiness that’s reminiscent of bacon.

Discover more iconic Canadian foods—and the best places in the country to find them.

Chicken Bones

For a brand renowned for chocolate, it’s ironic that Ganong’s signature product is relatively light on chocolate content. The company’s “Chicken Bones” candy was created by confectioner Frank Sparhawk in 1885 and remains a best-seller today. These bright pink, spicy cinnamon candies contain a bittersweet chocolate centre and can be found in just about every Maritime household during the holiday season. Look around New Brunswick and you’ll see Chicken Bones-inspired lattes, brownies, ice cream, and even a liqueur!

The Chocolate Museum

St. Stephen and Ganong’s shared history is celebrated at The Chocolate Museum, which was established in 1999 at the old Ganong factory. The museum offers fascinating tours that cover how the once-exotic cocoa bean changed the community forever. Such was the demand for chocolate—as well as employees that could keep up with the pace of production—that Ganong even established a boarding house for their female staff in 1906. Photos of the young women of Elm Hall, as it was known, are on display at the museum, and their story leaves a lasting impression. Among these women were the elite chocolate dippers, whose high-speed skills at hand-dipping the gourmet chocolates became the stuff of legend. At one point, Ganong employed around 300 of these artisans, finishing each dipped confection with a swirl or splash of chocolate as distinctive as their signatures.

Here are more quirky Canadian museums worth exploring.

Visiting St. Stephen, New Brunswick

Michelle Vest, events coordinator with the Municipal District of St. Stephen, reports that delicious treats are just the beginning of St. Stephen’s attractions. Some of the non-chocolate activities around town include the International Homecoming Festival (which celebrates the friendship between St. Stephen and Calais, Maine), the Charlotte County Museum (which chronicles local life from the late 1800s onwards), and even the world’s oldest basketball court (which dates to Oct. 17, 1893).

There’s also an abundance of outdoor spaces worth exploring, including the Ganong Nature Park, which is a popular spot for hiking and picnics, as well as the David A. Ganong Chocolate Park, boasting a splash pad, bandstand and boat launch for the St. Croix River.

Come August, everyone in town is busy with the annual Chocolate Festival. Highlights of this beloved tradition include make-your-own chocolate bark workshops, a jellybean fun run, a pancake breakfast, treasure hunts, recipe contests, movie nights, and bingo. There’s even a pudding-eating contest—chocolate of course.

Even if you don’t have a sweet tooth, you’ll be welcome in St. Stephen. As Vest says, “We truly are a happening little town here in southwest New Brunswick!”

Round out your trip St. Stephen, New Brunswick, with these must-see sights on Canada’s east coast.

“They’ve become the sleep tool to have,” says Alanna McGinn, founder and lead sleep expert at Good Night Sleep Site, which operates out of Toronto. “I’m a huge proponent of them because they can work so well.” (McGinn and her “sleep consultants” are certified by the U.S.-based Family Sleep Institute.)

About 32 percent of Americans don’t get enough sleep, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; it recommends at least seven hours a night for adults. Insomnia impacts as many as 35 percent of adults from time to time, while 10 percent have chronic trouble falling and staying asleep.

Weighted blankets range between two and 14 kilograms; choose one that’s around 10 percent of your body weight. Inside is a layer of plastic, glass or metal pellets surrounded by filling.

McGinn says the blanket’s heaviness mimics a touch therapy called deep pressure stimulation. Just as swaddling babies can send them to sleep, these blankets help your heart and breathing rates slow and your body release feel-good hormones, including serotonin.

Are they effective? A 2020 review study in the U.S. looked at eight previous studies and concluded that weighted blankets helped reduce anxiety—but not necessarily insomnia.

But other 2020 research tells a slightly different story. A randomized controlled study in Sweden looked at 120 people with insomnia and also depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Those who used a weighted blanket had better sleep and were less tired, anxious and depressed in the day.

People with circulatory conditions such as diabetes, or breathing issues such as asthma or sleep apnea, should check with their doctor before using one. “And if you’re someone who gets a little claustrophobic, it’s probably not the best thing for you,” adds McGinn.

Now that you know the science behind these weighted blanket benefits, find out 12 secrets to a good night’s sleep.

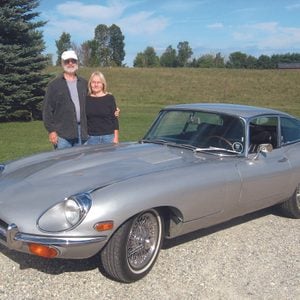

When my husband Arend retired after a 40-year teaching career, he wanted to do something completely different during his retirement years. He decided to restore antique cars, the older the better, and learn to do every aspect of the restoration process himself.

To that end, he joined the Edmonton Antique Car Club and purchased two old cars from a fellow club member, a 1930 Essex Challenger sedan that was mostly complete and a 1926 Chevrolet Superior Touring Sedan, a basket case that literally came in boxes.

After finishing the restoration of the Essex, he started restoring the 1926 Chevy. Arend made new hickory spokes and restored the wooden artillery wheels which were in very poor condition. The car came with a 1928 motor which was seized and the block was cracked. He disassembled the motor, freed the pistons, “pinned” the crack in the block, put in new rings and one new piston and eventually had the engine running as it should.

Next he disassembled, cleaned, repaired and painted the frame and the rest of the mechanical parts. Car bodies at that time were still built with a wooden frame with sheet metal nailed to the outside. This car had obviously spent much of its life abandoned in a field somewhere and much of the wood was rotted and a lot of the sheet metal was rusted out. He replaced the rotten wood frame with new wood. Arend bought himself a MIG welder and taught himself to weld; he cut out and replaced the corroded metal. He completed the body work, constructed a temporary paint booth and painted the car body and all its parts.

After he reassembled the newly painted car, Arend did the upholstery, making the seats, the interior, and eventually the top. It was his first time behind a sewing machine and I had to give him some pointers. Since it was a touring car—the early version of a convertible—he made wooden top bows that he steam bent into the required shape. Arend loves wood so the floor boards, the steering wheel and the running boards are all natural finished oak. Eventually, everything was finished, a safety inspection was passed and it was licensed, insured and ready to hit the road.

It’s a fun car to drive, especially on a warm sunny day with the top down. It gets lots of attention. Everything is more or less original so it drives like a 1926 car with no shocks and rear brakes only. We do have to be very careful in modern traffic. For safety reasons Arend has installed signal lights, seat belts and side mirrors. On the highway it drives comfortably at 40 to 45 mph and it’s amazing how much more you see of the countryside at that speed. We try to stay off the main roads and highways. The front seat is rather narrow as on all cars of that era so driving together is nice and cozy.

It took him about four years to finish this car. He has shared what he has learned with other club members, as well as the public in general, by writing numerous articles for the club newsletter The Running Board and posting several YouTube videos.

Over the years we have driven it to various car shows, seniors’ residences, tours and other club events. After finishing this car, Arend has gone on to do a complete restoration of a 1929 Willys Whippet sedan and is currently working on a 1952 Ford F1 pickup. He is a very talented man!

Next, check out an impressive 1930 Cadillac sedan restoration.

No doubt about it, there are definitely two different camps on how to arrange utensils in the dishwasher. It’s almost as controversial as the great “over or under” toilet roll debate.

One position is the one that Leslie Reichert, The Cleaning Coach, grew up with. “My mother insisted that the silverware was put in handles down so that when the utensils were rinsed and dried, the drops would roll down to the handles, and not leave spots on the food surfaces of the silverware,” she says. As for sharp knives? She put those facing downward, Reichert says. The opposing argument is to load silverware with handles facing up so you can put them away without getting germs from your hands on the eating surfaces of the silverware.

Most major dishwasher manufacturers agree on one thing: Load knives with the blades down and the handle sticking up for safety’s sake. According to Tod Colbert, founder of Wisconsin contractor and remodeler Weather Tight, the proper way to load silverware utensils is in the basket “with the handles up to, most importantly, protect one’s hands,” he told Reader’s Digest. In particular, he recommends keeping knife blades down—not just because they’re sharp, but because keeping the blades down will keep them sharper longer. “The dishwasher has been known damage knives, so it might be best to hand-wash your really good/sharp ones,” he suggests. Your best knives are some of the things you should never put in the dishwasher to start with.

Now, Reichert agrees with major dishwasher manufacturers about placing silverware handles in the up position. “I also recommend this if you are having your children learn to empty the dishwasher, or you really want to avoid transferring germs from your hands to the eating surfaces of your silverware,” she says. So there you have your answer: The experts agree, handles up!

Reichert and Colbert also agree about another tip for putting silverware in the dishwasher: Don’t group cutlery of the same type together. As Colbert explains, “Separating silverware so that forks, knives, and spoons are mixed and evenly distributed allows the water to pass through each utensil more easily, resulting in a cleaner result.”

Next, find out the surprising ways you’re shortening the life of your dishwasher.

Participants claim the practice of cold-water therapy—which involves plunging into or swimming in water no warmer than 15 degrees Celsius (roughly 10 degrees colder than the average pool) leaves them invigorated, clear-headed and even alleviates pain.

Cold-water therapy has become more mainstream in recent years, in part due to the influence of Wim Hof, a Dutch extreme athlete who developed his own method of cold therapy coupled with conscious-breathing techniques, but it’s not a new trend. In fact, cold water has been used to promote health for more than 2,000 years: ancient Greeks used water therapy to relieve fatigue and treat fever.

In Scandinavian countries, a traditional sauna session is sometimes followed by a cold plunge. Alternating between hot and cold temperatures increases blood flow in the skin and boosts circulation. High-performance athletes also use ice baths or cold showers to help mitigate the delayed-onset muscle soreness that follows intense exercise. And recent research suggests impressive benefits for mental health and stress management.

“Getting into cold water creates stress on the body,” says Dr. Mark Harper, an anesthesiologist based in the U.K. and Norway and the author of 2022’s Chill: The Cold Water Swim Cure. “The body reacts like it would to any stress: adrenalin and noradrenalin are released, your blood pressure and heart rate increase and your breath quickens.”

Unlike the detrimental effects of chronic stress, however, this type of wilful and controlled stress can be beneficial, according to a 2019 U.S. study published in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.

Apparently, combining physiological stressors, such as cold-water therapy, with focused meditation can train the brain to deal with the stress. Each time a person conquers the cold and emerges feeling invigorated, it reinforces the expectation of a positive outcome. The researchers believe that these brain changes extend beyond cold tolerance and could be applied in everyday life.

Positivity also played a part in research conducted in the U.K. and published in a 2020 issue of Lifestyle Medicine. The small study followed 61 people as they took a weekly cold-water swimming course over 10 weeks. At the end of the study, participants reported greater improvements in mood and well-being than the control group on shore.

Cold exposure increases “feel-good” hormones, such as serotonin and dopamine, says Harper, one of the study’s authors. Swimming is also good exercise and often a social activity, which helps to offset anxiety and allows the body to feel both pleasure and motivation.

Harper has been cold-water swimming for nearly two decades and compares the stress of cold-water therapy to that of intense exercise. “Done safely, it’s a pretty effective way to train the body,” he says. “But if you’ve got a heart condition, you’ve got to be careful.”

If open water isn’t your thing, you could try cold showers. One 2016 Dutch study published in the journal PLOS One found them to have a positive impact on immunity: subjects who took a cold shower every day were 29 percent less likely to take time off work for illness.

For those wanting to try cold-water swimming in a lake or ocean, ease into it with short exposure times—just long enough for your body to get past the initial shock. Never start by plunging your entire body in at once, and always swim with a friend. Gradually increase the time you spend in cold water to three or four minutes, at least once a week. “That’s all you need to get the benefits,” says Harper.

Now that you’ve learned about the benefits of cold-water therapy, find out what activated charcoal really does.

When my husband talked me into rescuing a dog a few years ago, I worried about the downside: fur all over everything, arguments over walk duty. The time for a dog was decades ago, when we had a son at home to play fetch. At 65, we should be planning our next trip overseas, but Paul had always wanted a dog. For love of my husband, I said yes. But I doubted I could love any dog, much less the only condo-friendly dog on offer, a ragged-eared mutt.

He had a great story, I’d grant him that. Born unwanted in Ohio, taught to sit and stay in a prison where incarcerated people train pups for adoption, then sent to a shelter where he waited for a home until he was spirited away to Toronto by a band of volunteers dedicated to saving dogs from death.

We named him Casey. The first thing he did after galloping into our home was drench a chair with pee. He sniffed every corner and finally came to rest with his warm muzzle on my thigh. Maybe I could love him after all.

Our First Walk

On Casey’s first morning I briefly forgot we had a dog. I padded out of bed, fuzzy with sleep, to find another creature sprawled on the TV couch. This had happened a good many times before, but in the past that creature was my husband, sleeping in the very spot where I meant to lounge with my second cup of coffee and the obituaries section of The New York Times. Paul sleeps best anywhere but the bed, and the TV tends to get him nodding in the small hours. The presence of a dog—our dog—was a marvel. Oh, yes. It’s you.

Casey seemed to have expanded since the three of us had curled up with Grey’s Anatomy, two to watch and one to snore. In his languor, he pretty much filled the space, limbs every which way. His torn ear pointed straight up; the other flopped off the couch. I perched on the ribbon of space he’d left me and stroked his flank. Up went all four paws, his way of wishing me good morning. And a fine morning it was, with Casey in it.

My ideal morning involved leisurely online perambulations in my bathrobe. At least it had until this day. But Casey needed his morning walk, which fell to me as the resident morning person. I couldn’t be late, or he’d have an accident.

Everything we knew about Casey we’d learned from his foster mom, Liz, who handed him over to us. She said I should take him out right after breakfast. Liz had a fenced backyard; all she had to do was open the door. Then she could hang out in her pyjamas if she chose. Maybe make some muffins, do a crossword, call her mother. But Paul and I lived on the eighth floor of a downtown Toronto condo building. For me, Casey’s morning routine required lipstick, eyebrow pencil and presentable attire.

I’d laid everything out the night before—jeans and sweater for me, poop bags and liver treats for Casey. His crimson leash hung on the coat stand. I remembered Paul’s first attempt at walking Casey, the circular stagger outside Liz’s house. I was in for a challenge with this bruiser. Whoever trained him knew something Paul and I didn’t.

In my days working in publishing, I used to pull creative people into line. No, you can’t leave work when we’re in crisis mode, summer hours be damned. You want to misspell a headline “because it looks better that way”? Go back to fourth grade.

After all the humans I’d tamed, how hard could it be to walk a dog? People did it while texting, hauling groceries and easing strollers over snowy curbs. The bolder ones did it on skateboards and bikes, and my neighbourhood’s fastest canine, a shepherd mix in an orange vest, scurried alongside a man on a scooter. Clearly, anyone could walk a dog—you didn’t even have to be ambulatory.

This morning, we’d barely set out when a call rang out from behind, followed by a burst of laughter: “Who’s walking who?” Good question. We couldn’t seem to find our rhythm. Every few paces, a standoff ensued. My will against Casey’s nose.

That nose. Low to the ground, sweeping the air, pulling us forward on a full-tilt quest for anything that smelled edible. Down in one running bite went the soggy pizza crust, the nub of chicken in the gritty remains of its batter. Casey dragged me where the nose commanded, shoulders pumping. The exquisite precision of his nose recalled a hummingbird skimming a flower, yet the prize it sought might be the bloody feathers of a crushed pigeon or vomit from someone’s drunken spree. No relic of a living or once-living creature was unpalatable to Casey.

When not engaged in the quest for food, the nose evaluated spots for a pee. Casey zipped across the sidewalk like a daredevil driver cutting through three lanes of traffic, and came to a lurching stop at the hydrant summoning his nose. There he checked the accretion of canine pee that proclaimed to the neighbourhood dogs, I was here! He took his sweet time while a yellow rivulet spilled over the sidewalk and into the street. No matter how lavish the spray, he always had pee in reserve for the ritual known as marking.

I thought I knew what it meant to walk my downtown neighbourhood. Check out the movies playing at the local theatre. Take note of a shoe sale, a new wood-oven pizzeria. Eavesdrop on conversations. All the while setting a pace, getting my exercise while my mind floated free. Walking was my gateway to an inner world in which I chose where to direct my attention.

Not with Casey. I veered between meandering, waiting and a fair approximation of a drunken shuffle, both hands gripping the supposedly handsfree leash that looped around my waist (the dog walker’s equivalent of training wheels). Paul and I had a plan for Casey’s walking, an hour a day from each of us. Why had I worried about Paul holding up his end, when I was the slight one trying to stay on my feet?

Pedestrians swerved to avoid us; hazards loomed on every block. Casey tried to chase cars that looked wrong for unfathomable reasons (just when I thought it was only orange cabs that set him off, he’d charge a black minivan).

And that was the easy part. Squirrels sent him into warrior mode, with head-turning ululations and acrobatic leaps that nearly knocked me to the ground. Before Casey, squirrels reminded me adorably of Beatrix Potter’s Nutkin. Now they seemed more like battle-hardened ruffians on Game of Thrones, a tribe of them always ready to burst from the nearest sapling.

While flying at a squirrel I hadn’t seen in time, Casey ran smack into a couple of pedestrians. The woman flashed a tolerant smile; the man scowled at me over his shoulder. At the rate we were going, someone might get hurt. Come to think of it, my shoulder was hurting already. I’d heard of strength training for golf and skiing, but dog walking?

I checked my watch. Five more minutes and we’d finish the hour. We. The right word for Casey and me on the couch, gazing into each other’s eyes.

Out on the street there wasn’t any we. Intellect against instinct, that’s what there was, intellect being the loser. We couldn’t make it home fast enough.

Just as I let my guard down, Casey had a set-to in the lobby with a neighbour’s Lab, Betsy, infamous for roving the halls at night. Her owner looked us both up and down, lip curled. “Rescue dog?” To lighten the mood, I mentioned Casey had spent his puppyhood in prison. “You’re brave,” he said, pulling Betsy away from my jailbird.

The elevator seemed to crawl to the eighth floor. Casey ran to Paul’s arms for some vigorous rubbing and the question that cannot be asked less than twice, with escalating volume: “Who’s a good boy? Who’s a good boy?”

“Casey! Casey!”

We had a good boy alright, but it soon became clear that we’d both have to up our walking game.

Paul got into trouble at St. James Park, beloved for its gazebo and landscaped gardens, when Casey had a noisy meltdown over a squirrel. A tweedy codger shook his finger at Paul. “That dog of yours is a nuisance. Don’t you realize some of us come here for a little peace and quiet?” He pointed to a wisp of a dog perched on its owner’s lap like a stuffed toy on a satin pillow. “That’s how a dog should behave. And until your dog gets the message, I suggest you keep him out of this park.”

The night after Casey was exiled from the park, he lay on what we already called “Casey’s couch,” twitching as he snored. I ran my fingers along the cleft in his skull, where his ginger fur darkened to rust. I’d never know for sure what Casey dreamed, but I figured a squirrel was involved. Go, Casey, go. Run the varmint down.

A dog trainer, Laurie, soon paid us a house call. She looked younger than our daughter would be if we’d gotten around to having one, but dog people on Yelp said she knew her stuff. I’d told her to expect a squirrel-crazed, trash-chomping rescue mutt, billed as a Lab/pug mix, although who could say for sure?

Laurie was sure. “He’s all hound.” With that pointy snout, he couldn’t be anything else. And this explained a lot about our would-be squirrel assassin. Like every hound who ever chased prey, Casey was designed for the task, with a nose that ranks among the wonders of the animal kingdom. His “squirrel attacks,” as we called them, expressed his greatest gift. Some dogs were born to bark at strangers; ours was born to hunt rodents. I figured we had the better deal.

Laurie put Casey through a few paces. He sat, stayed, lay down as he had been taught in prison—and as he’d do for us if we learned to speak his language. “You lucked out with this guy,” Laurie said. “He wants to please.” He could have fooled me, but Laurie was the pro.

The three of us took Casey to a free-and-easy park where teens shoot hoops and no one would get fussed about a ruckus. The idea was for Laurie to watch Casey do his worst, and as we neared the first squirrel-inhabited tree he rose—no, soared—to the occasion with his full repertoire of sound effects while I, the clueless human at the end of the leash, stood and bleated, “Casey, stop!”

I half-hoped Laurie would exclaim at his antics. If Casey had to raise hell, let him be the loudest, most epically acrobatic hell-raiser she had yet seen. How many squirrel-chasing dogs do back flips, then jump up to try again? For him the leash did not exist, nor did failure. Every squirrel was a promise of victory. Casey was my Don Quixote charging at windmills, my pratfalling Buster Keaton.

Laurie watched the show with her hands in the pockets of her hoodie; she’d seen every move before. “Like I said, all hound. You want his attention on you, not the squirrel. That’s going to be your challenge. So let’s get to work.”

The Lauries of this world don’t really train dogs. They teach perplexed humans to stop doing what doesn’t work and acquire more constructive habits. Laurie reminded me a little of Annette, our couples’ counsellor back in the striving years. Whatever long-forgotten muddle we were in, she’d seen it all before.

How hard we’d worked with Annette in her basement office with the pine-panelled walls. How thoroughly we’d prepped for every session. If she’d given marks, we’d have aced her course. “You’re remarkably well-matched,” she once told us, peering through the enormous glasses women wore in the days of shoulder pads. “It’s a miracle that you found each other.” Her version of Laurie’s “You lucked out.”

With Annette, Paul and I tuned in to the sometimes mystifying but basically well-intentioned people we were at heart. We were about to begin the corresponding process with a dog, who had never forgotten a birthday, stormed out in a huff or blamed either of us for a thing. Compared to making a marriage, training a dog should be a snap.

I wasn’t getting through to Casey, Laurie said. My entreaties were meaningless noise, a sound soup of his name and half-hearted marching orders. Nature gave Casey a mission: slaughtering creatures who, in his mind, had no right to exist. To interrupt him, I’d have to make some noise.

I had three options: whistling, shouting or a vigorous hand clap. I never learned to whistle, and clapping is no good with gloves on. That left shouting. As squirrel after squirrel romped by, I tried to summon a respectable shout: “Casey! Casey!” How could it be that the name I loved to murmur was so hard to shout with conviction?

Paul shook his head (in our class of two he was the star). Shouting had always come easily to him—too easily for my liking, but with dogs it served a purpose. “More authority,” he said. “More volume.”

The authority part I could nail. At 65 I’d damned well earned the right to be a feisty old dame. I demanded refunds with aplomb (and got them). I told wait staff not to call me “dear” and shambling 20-somethings to make room for me on the sidewalk. I complained and corrected with ease.

But nobody loves a woman who shouts. In my childhood home it was well understood that only my father had the right to shout—and he could erupt without warning. Sober, he quoted Yeats to my sister and me at bedtime. When we modelled new outfits, he would bow to us and ask, like a gentleman from an old movie, “May I have your telephone number?” (Telephone: an old-fashioned word, even circa 1960.)

But when he was drunk or hungover, the smallest thing could get him going, like the double boiler for his oatmeal. “What’s become of the blasted thing? Is this any way to organize the kitchen cabinets?” The rest of us would wake to a percussion band of clatter. And I’d know in the pit of my stomach that the day ahead was going to be a stinker.

Fear had a sound: shouting. What I feared was not so much my father’s anger as my own. Because he was a man—the man of the house, in the language of those times—he got to blow off steam. Because I was a girl, I didn’t. I should keep my head down, stay out of Daddy’s way, do my best to placate this overgrown baby in the guise of a man.

Now I had Laurie’s permission to shout. More than that, I had marching orders. For Casey’s sake, I would learn to let it rip.

Us-ness

After our first session with Laurie, I walked Casey with her voice in my head. I practised shouting, “Hey!” when Casey jumped into predator mode. The pavement didn’t split and swallow me up. I sounded loud and proud. Better yet, Casey started to get it—not every time or even half the time, but often enough, especially if I followed “Hey! Ca-a-a-SEY!” with a sharp tug on the leash. Then the treat, then the neckrub. “Good boy,” I would say, as Laurie had taught me.

I was asking a lot of Casey. In the presence of a squirrel, he was anger incarnate. His eyes blazed; his hackles rose. I thought hackles were only an idiom until I saw the band of rage down Casey’s back, where his fur is darker and coarser. When they stiffen, he looks bigger, more threatening, as nature intended. He was an officer of the laws of nature, determined to wipe lesser creatures from the earth. One squirrel affronted him; a bobble-headed flock undid him.

Anger consumed him quickly but vanished with the squirrel. Casey’s anger had an urgent purity. Unlike any human I’d known, he didn’t hold grudges. He wouldn’t ruminate on what he could have done to that squirrel if not for me, the spoilsport clutching the leash.

Casey and I walked together as a biped and a quadruped, an aging woman and a young dog, a second-guesser and a creature of impulse. One who cleaned up, one who drooled on the floor. One who compared recipes for roasted Brussels sprouts, one who had to be restrained from licking barf off the sidewalk.

It was our differences that held my attention, rather than the shared pleasure of the outing. Casey had his world, I had mine, and therefore I didn’t think of him and me as “us.” But before long I found myself speaking of the places I shared with Casey—our places, mine and his. The mural where I posed him for a shot, the park where we made friends with a juggler practising his moves.

I was beginning to understand who we would be to each other. We were Us now, and it was enough. The unlikeliness of our comfort together magnified the joy of it. As long as squirrels roamed the streets and parks of Toronto, there would be passing bursts of anger that didn’t change a thing. What we had, as a woman and a dog, underscored the miracle of any two fallible beings, committed to opposing points of view, planting the stake in the ground that is Us.

Paul will be Paul, Rona will be Rona. In the beginning came a you, a me. One who slept late, and one who equated purpose with rising early. One who left the marriage when our son, Ben, was a toddler, saying, “I never loved you” (me, exhausted by my young marriage and younger child), and one who said, “It’s not over. Let’s try again.” One who knew what things should be, and one who didn’t get it (actually, that would be both of us). From differences and disappointments, we created Us. And as Us, we brought Casey home.

Us-ness, once you’ve found it, can accommodate a fair bit of tension. Some days I couldn’t stop Casey from charging at squirrels number one through 17, but he calmed down by squirrel 99. With a multitude of squirrels about, we always had another chance. I arrived at a grudging respect for the squirrels, who would stare Casey down with what looked to my human eyes like amusement.

Squirrel by squirrel, day by day, we started to find our groove. We sometimes walked entire blocks without incident, Casey’s tags clinking in time with my steps and his leash vibrating gently in my hand, now that I’d learned not to grip it. He knew every variation on our route. If I didn’t pick his favourite, he would tug, as if to ask, “You’re sure about this?” I was sure. A slight disagreement on the route was no big deal for a simpatico pair like us.

A Master of the Art of Sleeping

We were ripping through our value pack of poop bags. Casey was remarkably productive, often filling several bags in a single walk. I didn’t mind, though. Scooping gave me a chance to do one thing right every day. And the humble task literally grounded me.

It forced me to tend the cracked and mottled sidewalk, the sodden leaves at the edge of a walking trail. It was a bondage I shared with all dog folk who care enough to do the right thing. The woman bending from her wheelchair with practised caution, the elderly walker favouring a bad knee. The young parents exclaiming, as their toddler scooped for the family dachshund, “That’s it! Good girl!”

When I started walking Casey it was early spring, when receding snow exposed a winter’s worth of blackened excrement in every park. It clumped at the rims of hedges and dotted the sidewalks, a desiccated record of human can’t-be-botheredness. So many scoffaws about, making me a target for those who hold dogs in contempt. Some people hate dogs for jumping, others for disturbing the peace with their barking. What unites them all is their loathing of poop.

I’d just disposed of Casey’s first of the day when someone approached us with an open Clive Cussler novel in his hand and headphones blasting cacophony into his ears. As he passed, he yelled over his shoulder, “I hope it’s not your dog who just left his business on the sidewalk! It’s a pox on the city!”

The last time I’d heard the word “pox” used in the Shakespearean sense, I was trying to ace an English course. Full points to Mr. Multi-task for literary air, but his logic stung. He didn’t turn his head when I called, “Not us!”

Us. Any scorn directed at Casey is really directed at me. When you get down to basics, I was scooping because I loved him. I hoped my fellow humans would look benevolently on him, or at least not disdain him. Every time I bent for Casey, I proved that Yeats was right: “Love has pitched his mansion in/ The place of excrement.”

I no longer missed walking with Paul. Walking with a dog had distinct advantages. If Casey took any notice of my mood after a rough night’s sleep, he showed no interest in what this meant for him or when I might snap out of it. He still sauntered beside me, ears sliding back to catch a rustle in the grass no human could detect.

I didn’t have to earn the good cheer enveloping us. Its engine was Casey’s zest for the minutiae of his day—the stained wall that must be peed upon because no other wall compares, the postal clerk who must be greeted for a biscuit from her tin behind the counter. On Casey’s map of pleasures, I was like the earth and the sky, reassuringly present but not the focal point.

As Laurie had taught me, I crossed the street to dodge cats, darting toddlers, unpredictable puppies—anything that might flip Casey’s anger switch. He took exception to dogs off-leash (they made him feel insecure), dogs with enormous furry heads (not dogs, as far as he could tell) and a good many large black dogs (who knows why?). Meanwhile other dogs took exception to him for similarly unfathomable reasons. When I couldn’t remove Casey, I’d distract him by throwing a handful of treats about.

I knew we’d met a milestone when Casey had a full-throttle squirrel attack close to where we’d first walked with Laurie. Loud, proud and fast, I executed my three-step routine: the shout, the tug, the “Good boy.” Someone waved, a professional dog walker whose three charges were all sniffing the same patch of grass. “Nice work!” she called. How long had it been since I was asked, “Who’s walking who?”

One day I had a brainwave: Us-ness might serve a practical purpose. Casey has the enviable canine gift for sleeping anyplace he happens to be, from the back seat of the car to a friend’s yard. I have the human gift for rolling worries around in my brain when all I crave is sleep.

In the middle of a restless night, I went looking for a soporific book and found Casey zonked out on the TV couch. He didn’t stir when I sat down beside him to stroke the soft fur on his neck. He exhaled, sinking deeper into his rest. He sounded almost human, but then every human sigh is mammalian. Hey, Casey. Take me with you.

He’d left me just enough room to curl up and make his firm, warm chest my pillow. Unlike all other pillows in my life, Casey’s chest expands with his breath. His fur smells pungently of himself. No matter what he’s kicked up on our rambles or where he’s pushed his snout, he smells exactly as he does.

My headful of niggles rose and fell with Casey’s breath like a boat on a calm sea. I didn’t yet know I was taking liberties: a five-kilogram human head is a not-inconsiderable burden for the chest of a 14-kilogram dog, and any dog hates to be confined. But Casey was too far gone to throw me off right away. He supported me for about five breaths, enough to remind me how deep and slow a breath can be.

I’ll never paint like Matisse or write a poem like Emily Dickinson, but Casey let me believe that I could sleep like him, my personal master of the art.

For the sleep of my dreams, I’d gone to extraordinary lengths. Bought a king-sized mattress that adapts to my weight and body temperature, its materials developed by NASA. Followed a regimen of pre-bedtime baths and stretches. Taken heavy-duty sleeping pills. Consulted a sleep psychiatrist to help me kick the pill habit and learn the rules of “more efficient sleep.”

On a night of broken sleep not long after Casey joined us, I found him dead to the world on the couch. What he knew about sleep no human could teach me. Falling asleep, like falling in love, is about letting go of expectations, loosening your grip on control. I learned this watching Casey.

Sprawled or curled nose to tail, eyes shut or half open, he got the average dog’s 12 to 14 hours a day. All I asked was seven. With a little help from my canine coach, I had become a whole new sleeper.

It didn’t occur to me then that he could coach me better if he were in the bed, at my side. Roughly half of dog people sleep with their animals, but I’d made a rule—no dirty paws on our 300-thread-count sheets—and I was sticking to it.

I returned to the bedroom, where the sheets had cooled while I had been hanging out with Casey. My side of the bed looked like the shipwreck of my night so far—a tangle of sheets, eyeshades and layers of clothing added, then subtracted, in my search for the right body temperature. Paul’s side lay untouched while he slept in his favourite armchair.

I positioned myself on the neck-cradling pillow I need to take with me everywhere. The white-noise machine whirred. I replayed the moment Casey and I had just shared—his fur against my cheek, his breath lifting me—until I slipped into a dream of Us.

From the book Starter Dog: My Path to Joy, Belonging and Loving This World, by Rona Maynard. Copyright © 2023, Rona Maynard. Published by ECW Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Next, check out this heartwarming story about the bond between a woman and her Haflinger horse.

How Our Inspiring Daughter Faced Adversity With a Grateful Heart

Thoughts such as, “why her and not me?” ran through my mind after learning, in May 2017, that our youngest daughter, Colleen, had three cancerous tumours in her right breast. Devastating news—yes. But also the start of a journey that was a privilege to embark on with her. I learned a great deal about cancer and treatments, but more importantly, I witnessed an incredible strength of character, fortitude, wisdom and positivity that Colleen displayed while meeting the challenges of cancer.

Colleen’s treatment regime began with chemotherapy, followed by mastectomy and reconstruction surgeries and radiation. Hopes were raised when it appeared her cancer was in remission, but, unfortunately, a routine checkup in January 2019 indicated the cancer had metastasized. Treatments resumed with Colleen maintaining an active and rewarding life until March 2020, when her cancer became more aggressive and she was under palliative care at home, passing away peacefully on May 3, 2020. While undergoing treatments, Colleen would write email updates to family and friends as she chronicled her cancer journey. Within these writings were personal, insightful reflections on life and living—how she faced adversity with a grateful heart and a positive attitude. The following few excerpts from her email letters have been a source of inspiration to many and a window into Colleen’s approach to life.

Colleen’s Words of Wisdom

“We don’t often think of cancer as a gift, yet it is. The gift is in the experience of it all. It’s the opening up of eyes to just how precious life is; the realization of just how short life can be; the warming embrace of family, friends and strangers; the time given to slow life down and reflect; seeing the good in humanity; being thankful for great healthcare and being thankful in general. Cancer is scary for sure, but as with all things, there is still a silver lining to it, too—believe that it’s there and you will find it…

Life tends to fly by as we constantly look and plan ahead so that we sometimes miss out on the here and now; we lose sight of the importance of today and all that there is to be thankful for in the present moment. Remember to ‘live the moment’…

Life isn’t perfect, we aren’t perfect, yet in life there are moments that are perfect; moments where you can’t imagine being anywhere else, and moments where you realize just how thankful and blessed you really are. Those are the moments we need to cherish, to remember, to hang on to so that in times of worry, stress, frustration, fear, chaos and uncertainty, we have something to help get us through. A reminder that life has ups and downs, that life has good days and bad days, and that, although life doesn’t always go as planned, there are perfect special moments within it that make it all worthwhile…

Some things in life are out of our control, and that’s okay. A big part of life is learning to live in the chaos that it is. To know and understand that things won’t always go as we had planned or hoped for and that life is full of surprises, both good ones and not-so-good ones.”

Colleen lived her cancer journey with grace and dignity, inspiring many with her positive attitude, twinkling eyes and infectious smile. When it was suggested that her writings should be put into a book, Colleen started preparations to do so and the 229-page paperback or e-book Live the Moment—My Cancer Journey by Colleen McManus-Mullin is available here. Colleen’s writings and reflections are a wonderful legacy for her two young sons and to all who may benefit from her wise words of wisdom and cancer journey!

Next, check out these powerful stories of how organ donations have changed lives.

The 18-month-old lion cub, already bigger than a Great Dane, leaped out of the thick underbrush, put his furry front paws up on Tony Fitzjohn’s broad shoulders and rubbed heads joyously with his friend. It was Thursday, June 12, 1975, and in lion fashion Freddie was welcoming Tony back to Kora Camp after a two-day supply trip.

Kora, an isolated huddle of tents protected by a high wire fence in northern Kenya, was where 70-year-old naturalist George Adamson rehabilitated lions in a unique conservation project. Orphaned cubs or young zoo lions—animals that would otherwise remain in captivity— grew up, reproduced and lived free in an area the Kenyan government had designated as a national game reserve.

Conditions at the camp were rugged: intense heat and biting tse-tse flies, no electricity or plumbing and a six-hour drive to the nearest settlement. But English-born Fitzjohn, 31, had read the Born Free books as a teenager and been captivated by the story of Joy and George Adamson raising the orphaned lioness, Elsa. Living in Africa and working with Adamson for the last three years had been a dream come true for Tony.

One of his regular jobs was a monthly trip by Land Rover to buy supplies at the tiny outpost of Garissa. This morning, before his return, he had stopped to see the district game warden and thank him for evicting a gang of armed poachers who had been leaving poison traps for rhinos inside the reserve.

The warden had asked about Freddie, the abandoned lion cub he had found in the bush some 17 months earlier and turned over to Tony. It was the first cub Tony had known. He’d taken the frail, fluffy animal in his arms, driven him home to Kora and named him Freddie.

Later, three more cubs were brought from zoos. But Freddie always held a special place with Tony. Freddie was not only good-natured, but also the bravest of the cubs, scrappier and more inclined to take liberties with the fully grown wild lions that prowled around the fence. He and Tony had slept in the same bed until Freddie outgrew it. Tony’s girlfriend, Lindsay Bell, who was living in Nairobi, had noticed that he was completely relaxed only when he was with his lions.

After two days of rough driving, Tony was exhausted and glad to be back at Kora. He was dressed only in shorts and sandals, his tan skin glistening with perspiration in the 36-degree heat. It was 5:10 p.m., time to gather the cubs—the other three had joined Freddie now in welcoming Tony—and take them inside the fence for the night. To settle the frisky Freddie, Tony sat down, his back to the underbrush a few metres away, and began talking quietly. Though a rule in the bush is never to sit on the ground outside camp—because of the possibility of unexpected contact with animals—Tony felt safe just 50 metres from camp.

Without warning, he felt a giant creature pounce on him from behind. He crashed forward to the ground and momentarily lost consciousness. When he came to, it was to the terrifying awareness that his head was locked in the jaws of an enormous lion.

The attacker clamped down hard, then released the headlock and began a barrage of biting and clawing—sharp bites to the neck and head, deep bites to both shoulders, slashing claws to back and legs.

To Tony this horror was a series of jerky slides punctuated by blackouts. His glasses were smashed and he saw ashes of the camp he had thought close; it seemed to be moving farther and farther away, getting smaller and smaller. Which lion was attacking him? One of George’s? He only knew that the beast was fully grown and powerful.

Tony covered his genitals and closed his eyes. More blows from mighty paws struck his head; more deep gashes from razor-sharp claws opened his face. Because of shock and concussion, he felt no pain and heard no sounds. Paralyzed by injuries and bewilderment, he was experiencing his own death as a silent movie.

Now the lion grabbed Tony’s neck and bit down. Tony remembered that lions often kill by strangulation, holding their vise-like grip until the prey stops breathing. It takes no more than a minute.

Then he realized that there were two lions in the battle. As he forced his bloody eyelids open, he saw Freddie charging toward him. Oh, no, not Freddie, too! he thought.

But Freddie wasn’t attacking Tony; he was after the mighty lion, four times as big as he. Proper juvenile behaviour is to submit to adult lions. To attack an enraged adult was suicide.

Freddie, however, snarled and bit at the flanks of the lion that stood astride Tony’s torso. For an instant it worked. The lion released his grip on Tony’s neck and charged after Freddie, who ran for his life.

Tony lay in a pool of blood, gasping for air. The attacker could have torn Freddie apart on the spot, but he stopped his pursuit and ran back to the victim. Again, he clamped down on Tony’s neck. God, I’m dying! I can feel it, Tony thought, then lost consciousness again.

But Freddie returned to the fray and bit the surprised beast’s rear, then circled while making snarls and yelps, bold charges and nips. Freddie withdrew only when the bigger animal swiped at him with his powerful paw. Throughout the attack, Tony was a silent victim and the lion a silent killer. The only sounds were Freddie’s unrelenting growls and piercing yelps that Tony could not hear.

Freddie’s shrill cries were heard by Erigumsa, the compound’s cook. At first, he thought two cubs were fighting, but Freddie’s distant voice sounded too desperate. The cook ran to the gate and saw Tony being mauled. Erigumsa raced to the dining tent, 25 metres away, where Adamson was having tea.

“Simba ame kamata Tony inje! Anataka kuua yeye!” he cried in Swahili. (“The lion has caught Tony outside! He’s trying to kill him!”)

George assumed the cubs’ playfulness had gotten too rough. So when he ran from the tent he took only a walking stick, bypassing a loaded rifle.

But outside the gate, George saw Tony’s neck locked between the jaws of a full-grown lion. There was no time to return for the rifle. Without a second thought, he charged the lion, yelling and waving the walking stick.

Now George was vulnerable to attack. The beast released Tony and retreated, staring at George. The lion prepared to spring, but George kept moving forward, shouting and brandishing the stick. It worked! The lion hesitated, then slunk off into the bush, splotched with Tony’s blood.

The next thing Tony knew, he was stumbling back to camp, supported by George. “George, I think I’m dying. Whatever you do,” he pleaded, “don’t shoot the lion. My fault … Caught unaware … Shouldn’t have happened.”

The minute he got Tony into his tent, George rushed to the shortwave radio to call the Flying Doctor Service in Nairobi. It was too late—the 210-kilometre flight would take an hour and a quarter, and regulations firmly prohibit landing on a bush strip after dark, even for a critical emergency.

The nurse assured George that the plane would come first thing in the morning and advised him on first-aid treatment for Tony’s many deep wounds.

George signed off, staring at the setting sun. Could Tony make it through the long night ahead without a surgeon and blood transfusions?

Drifting in and out of consciousness, Tony fought for breath—and life. I’ve got to live—for Lindsay, George and the lions. I know if I just think about living, I’ll make it.

At dawn, George and Erigumsa managed smiles; 13 hours after his mauling, Tony was still alive.

Lindsay was the first one out of the Flying Doctor aircraft when it touched down—George had radioed her the night before. “I was expecting bad wounds, but not all over his head,” she recalls. “He could hardly breathe. The right side of his neck was open and his wounds were oozing. It was horrible.”

During the flight back to Nairobi with Tony, Lindsay broke down and wept. “I knew how much he loved his work,” she says. “If he lived, would he ever want to return to the lions?”

Tony spent two hours in surgery when they got him to the hospital. There were three dozen wounds—some so deep and dangerous they couldn’t be stitched at that time. His trachea had been squeezed but not broken. Miraculously, the lion’s teeth had not severed any nerve, artery or vein. Tony would be one of the few people ever to survive a lion-mauling.

The day after the attack, a large lion appeared outside Kora with dried blood on his chest and muzzle. It was a 30-month-old wild animal George had known since infancy, a creature so placid that he’d been named Shyman.

Now Shyman was growling menacingly at the cubs. George drove outside the compound and positioned the Land Rover between Shyman and the frightened cubs. Then he observed Shyman carefully. His movements were erratic, unusual.

The once-gentle lion had probably eaten from a poisoned carcass left by the rhino poachers. Since he had attacked once, he could do it again. The lives of humans and other lions were in jeopardy. After an hour of watching Shyman, George sadly raised his rifle and shot the lion dead.

Such a mauling as Tony had received would make even the bravest soul re-evaluate the risks of work in the bush. The scars on his face and neck would be with him always. But Tony remembered how a lion cub whom he loved had tried to save him.

Two months after the accident, Tony returned to Kora, wondering what kind of greeting he’d receive after his absence. When the cubs saw Tony, they rushed toward him, Freddie in the lead, making woofing sounds all the way. Typical lion greetings last less than a minute; this one lasted close to 10 minutes as the excited cubs leaped all over Tony.

“I never had any thoughts about not going back,” Tony said later. “We’re creating an animal reserve. People from all over the world can eventually come and see our lions, and the lions can live free and unmolested in nature. I belong here.”

Tony Fitzjohn continued to work at Kora until 1989, when he moved to Tanzania to lead efforts to rehabilitate a national park that had been decimated by farmers and poachers. Elephants are once again flourishing in the area, and Fitzjohn also helped bring rhinos back to Tanzania. In 2006 he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his conservation work.

In 2020, he returned to Kenya with his son Alexander to restore Kora, which had fallen into neglect after George Adamson’s death in 1989. “Everything that I am today, I owe to Kora,” Tony told Gentleman’s Journal in 2021.

Tony Fitzjohn died in May 2022 of a brain tumour at the age of 76.

Next, read this chilling story of a rogue bear attack at Liard Hot Springs.

When the snow thaws after a long winter, it’s time to weed, aerate and clean up your lawn. One common early spring complaint? A brown, spotty, half-dead lawn from all that water. Well, lucky for us, TikToker @Homespiff (@lbhomespiff) shared their simple, affordable hack to reseed dead grass patches. In this article, we’ll walk you through the entire process, so your lawn will be greener than ever in no time.

What do I need to reseed dead grass patches on my lawn?

According to the video, all you need to reseed the dead grass patches in your lawn is toilet paper, grass seed and water. For the toilet paper, you’ll want to use an untreated, natural variety that will biodegrade easily. Look for toilet papers that are marked as specifically friendly for RVs or septic tanks, or bamboo varieties.

How to reseed dead grass patches using toilet paper

Now, it’s time to make the grass-patching mixture. In a large bowl, mix the grass seeds with enough water to make a slurry, as shown in the video below. Then, add enough toilet paper so that you create a sludgy mixture, much like papier-mâché. Finally, apply the toilet paper-grass seed mixture to the dead patches in your lawn. Use a layer about an inch thick to give the seeds a chance to sprout. Now, just wait! According to the video, grass will begin to sprout after seven days.

@lbhomespiff Have you tried this?? Cool hack….or not? 😅 #gardenhack #gardening #foryou #inspire ♬ original sound – Homespiff

Benefits (and drawbacks) to this toilet paper grass seed hack

Some commenters on the video have pointed out that you could just use topsoil instead of toilet paper, and of course that’s true. Other commenters have raised concerns about the sustainability of this hack. If you are using biodegradable toilet paper, this should not be an issue. The biggest benefit to using toilet paper is that it’s cheap, easy and quick. Additionally, the toilet paper will protect the grass seeds from scavenging birds and keep them suitably moist.

Next, check out 20 gardening tips that’ll save you time, money and effort.