Why Teal Pumpkins Are Popping Up Around Halloween

Whether you carve or paint, it’s practically an obligation to decorate any pumpkin you get your hands on. But for some, those decorations are about more than creating a seasonal work of art. If you see any pumpkins painted teal this Halloween, take note. They have a very important meaning. (Choose calorie-conscious candy this year with these Halloween diet tricks.)

Halloween can be an exhausting time for families with children who have food allergies. It’s seemingly impossible to know what kind of candy and food will be placed into your child’s bag, which may pose as an immense threat to their health and well-being. In fact, according to the Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE), one in 13 American children has a food allergy, about two in every classroom. (Check out these 10 fascinating Halloween customs from around the world.)

Fortunately, FARE’s Teal Pumpkin Project ensures a happy and safe Halloween for children with and without allergies. Porches decorated with teal pumpkins during trick-or-treating indicate that non-food treats are being offered at that particular household. Some examples include stickers, bubbles, or glow sticks.

The now-worldwide movement was launched as a national campaign in 2014, but it was initially inspired by a local allergy awareness activity that took place in East Tennessee. The color teal has been associated with food allergy awareness for nearly 20 years, hence the teal coloured pumpkin. (Want to personalize your teal pumpkin? Here are 27 free pumpkin carving stencils to try out).

According to the FARE website, almost 18,000 households in the US participated in the project last year. People who wish to participate this year can add their homes to the project’s participation map and see if their neighbors are participating as well.

Plus: 5 Famous Ghost Stories with Totally Logical Explanations

Jack-o’-lanterns, haunted houses, creaking floorboards, dark woods, dead trees, howling wind: all things that come to mind when you think of a spooky Halloween night. But what makes the sound of the wind blowing through the trees and the leaves being rustled around on the ground so creepy? It’s just wind, right? (A mysterious hum has been haunting the town of Windsor for years.)

There’s actually a scientific reason why the howling breeze sends shivers down our spine, reports Mental Floss. Wind howls when it’s broken up from passing through or around objects, such as trees. The gust of air will split up to move around the tree and then comes back together on the other side. Due to factors such as the surface of the tree and the air speed, one side of the wind is going to be stronger than the other when the currents rejoin. The mixing of the two currents causes vibrations in the air, which produce that ghostly howling noise that gives us the creeps.

If there are leaves on the trees, they absorb some of the vibrations. That’s why you never hear the wind howling in the middle of summer—only around Halloween when the leaves are falling off the trees, or in the dead of winter. So, the reason everyone finds howling wind so creepy is because it’s associated with the Halloween season when the trees start to become bare, or with the dark, vast, naked forest in winter.

Want to get scared? Try visiting these 9 of Canada’s Most Haunted Places!

Take a closer look at that small, rectangular booklet in your hand. Depending on where you’re from, its colour could tell you a lot about the country you call home. (Don’t miss learning more about the rarest passport in the world, too.)

Although there are no strict international guidelines for passport colours, the shades are by no means random. Countries typically choose colours that pay tribute to their culture, politics, or faith, Claire Burrows of De La Rue, a British passport-making company, told the Economist.

For example, Islamic countries often use green passport covers because the colour is important in their religion. Member countries of ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States) cover their passports with various shades of green, too. Members of the European Union, on the other hand, use burgundy-coloured passports, as do countries who would like to join the EU, such as Turkey. (Here are 10 Rude Manners That Are Actually Polite in Other Countries.)

The United States tends to march by the beat of its own drum, and its passport’s hue is no different. While the country flipped between beige, green, and a variety of reds into the latter half of the 20th century, it finally settled on blue in 1976. As for the shade? It matches the blue on the American flag, according to the Economist. Citizens of many Caribbean and South American countries, including Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, also carry blue passports.

And we’re not even close to finished yet! Smaller organizations have their own passport colours, as well. Interpol provides its members with black travel documents, while the UN passport’s pacific blue matches the helmets of its peacekeeping force.

But why all of the dark shades? According to Bill Waldron of Holliston, a Tennessee-based passport-printing firm, darker colours are preferred because they can hide dirt, provide a nice contrast with the crest, and appear more official. There are some exceptions, of course. If you’re a Swedish national who lost your passport, the country will send you an emergency travel document—in pink.

Plus: 13 Things You Didn’t Know About Strange International Laws

When it comes to the royal family, some rules only apply to certain members of the family, like the one that makes sure you always see Queen Elizabeth wearing gloves. Some only apply when the royals are out in public, but not while in private. Others are broken on occasion, but overall royal protocol is strictly followed—like these etiquette rules everyone in the royal family must follow. But there is one rule that Prince William and Kate Middleton have been breaking for a while now.

You’ll observe this rule-breaking every time you see them arrive in a new country; the family travels together. A royal family tenet generally prevents so many heirs to the throne travelling together in case of an accident or crash. The rule has a similar rationale to the United States’ “designated survivor” rule, which places a Presidential Cabinet member in a safe location away from the location of the State of the Union, in case a catastrophe occurs which wipes out the bulk of the President’s line of succession.

The first instance of the rule break came back in 2013 when Prince George was set to head off to New Zealand and Australia for a quick tour with his parents. The rule would dictate that Prince George would travel separately from his father, but they all took the same jet. And since then, the family has always travelled together.

The reason for the rule is grim, but it isn’t the only dark regal tradition—here are eight words you’ll never hear the royal family say.

Plus: This is Why Prince William and Kate Middleton Never Show PDA

Audrey Hepburn: the Breakfast at Tiffany’s star remains a style icon even 25 years after her death (in fact, people are still dressing up as her for Halloween). She played a major part in the popularity of the little black dress, and, with a 5’7″ stature and 110-pound weight, had an enviable figure. In fact, many have speculated that she had an eating disorder, but she did not. For most of her adult life, she led a very healthy lifestyle. In an interview with People, Hepburn’s family revealed the “secret” to her lifelong slim figure—and there’s really nothing secret about it.

According to Hepburn’s son, Luca Dotti, his mother never dieted; in fact, she “loved Italian food and pasta.” He adds that she ate “a little bit of everything,” but ate more grains and less meat. Robert Wolders, Hepburn’s significant other for the last 13 years of her life, also shares details about her daily eating habits, and they’re really…normal. For breakfast, she would eat toast and jam; for lunch, veal, chicken, or pasta; and for dinner, often soup with meat and veggies. After dinner, Hepburn would indulge in a few pieces of chocolate and often a little bit of Scotch as well.

And yes, she did exercise, but again, nothing extreme. Wolders says that he and she used to walk a lot, and that “she could outwalk [him].” However, her exercise regime was always balanced and manageable.

So it seems that she owes her slim figure, in part, to practicing moderation, though Wolders admits that she did have a very healthy metabolism. (Here’s how to boost your own metabolism at any age.)

However, Hepburn’s weight wasn’t always healthy; in fact, she spent much of her youth battling starvation. She was born in 1929 in Europe, and lived in the Netherlands during the German occupation of the nation. For a traumatic few years, she survived mainly on plants such as tulip bulbs. Until the liberation of the Netherlands in 1945, she was sick with jaundice and dangerously underweight. However, as we know, she went on to lead a very healthy lifestyle…not to mention become a cultural icon.

Plus: 30 Healthy Snacks No Adult Has to Feel Guilty About Eating

In North America, practically everything goes into the fridge—including foods that would be better off on the counter or in the cupboard. And then we hear something that rocks our world: Europeans keep their eggs on the counter. In fact, they strongly recommend against refrigerating eggs. What gives? Two different philosophies about preventing the same nasty bug—that’s what.

At the root of the issue is salmonella, one of the most common causes of bacterial food poisoning. It can run rampant through chicken farms, turning up on the outside of eggs thanks to contamination from dirt and feces; more insidious is when its inside the shell thanks to the bacteria infecting a hen’s ovaries. To combat the problem, back in the 1970s the U.S. perfected egg washing: After laying, the eggs go straight to a machine where they’re shampooed with soap and hot water. This steamy shower washes away any potential salmonella, but it also strips the eggs of a thin coating called a cuticle. Without this protective layer, the eggs can’t keep water and oxygen in, or harmful bacteria out. So the eggs are refrigerated to combat infection.

European food safety experts took a different tack: They left the cuticle intact, made it illegal for egg producers to wash eggs, discouraged refrigeration (which can cause mildew growth—and bacterial contamination—should the eggs sweat as they come back to room temps), and started a program of vaccinating chickens against salmonella. The approach appears to be effective: In 2000, the UK had more than 14,000 egg-related cases of food poisoning; in more recent years, after their egg safety measures had been widely adopted, the number had dropped to 8,000. The U.S. has about 79,000 cases, but with a much larger population, of course.

There are objective and subjective pros and cons to room temp eggs versus refrigerated ones. When refrigerated, eggs have a longer shelf life—they’re good for about 21 days on the counter, and nearly 50 in the icebox. Refrigeration, however, means the eggs can absorb odours and flavours from other foods in there; countertop connoisseurs claim the room temp eggs taste better. But if you keep eggs stored in their carton, and minimize the amount of smelly food in your fridge, off flavours shouldn’t be an issue. Some chefs believe room-temperature eggs to be ideal for baking; it’s why you’ll see recipes recommending you bring eggs to room temp before mixing.

If you want to try room temp eggs, head down to the local farmers’ market and talk to the sellers down there. Chances are they haven’t washed or refrigerated, the cuticle is intact, and you could keep the eggs on the counter. See if you can tell the difference—just remember to practice consistency: If an unwashed egg goes in the fridge, it should stay there until you’re ready to use it.

Many people avoid saying “I’m sorry” because admitting to wrongdoing makes them uncomfortable.

“Apologies force us to admit to ourselves that we don’t always live up to our own standards,” says Ryan Fehr, a professor at the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business.

Research shows that apologies can ease your conscience, improve mental health, repair damaged relationships, kickstart the forgiveness process, increase trust and boost self-esteem. Experts advise:

Build your apology. Ohio State University researchers found that effective apologies have six components: Expressing regret, explaining what went wrong, acknowledging responsibility, declaring repentance, offering to repair the situation and requesting forgiveness.

“The more of those components that were included, the more likely the apology was seen as credible,” says study author Roy Lewicki.

Consider timing. Delay apologizing if your victim is angry; it may stop him from being receptive, says Antony Manstead, psychology professor at Cardiff University in Wales.

Delayed apologies can also be effective because you’ve had time to reflect upon your transgressions, says Mara Olekalns, professor of management at Melbourne Business School. But wait too long and you’ll appear remorseless.

Choose your words. Avoid these pitfalls:

Making excuses. “People often water down their apology with excuses,” says Roger Giner-Sorolla, professor of social psychology at the University of Kent in England. “Admitting wrong [may] make you worried that you’re a bad person.”

Belittling feelings. “[Implying] that the other person is wrong to feel upset or angry,” Olekalns says, “diminishes and invalidates their experience.”

Pointing fingers. “[This] is deflecting responsibility onto the victim for being too sensitive,” Fehr says.

Offering a non-apology. ““It uses the form of an apology – ‘I’m sorry’ – but [shifts] responsibility to the offended person,” Giner-Sorolla says.

Pick a medium. Face-to-face apologies are best; facial expressions, body posture and tone of voice can convey remorse.

“Anyone can type, ‘I feel really ashamed,’ but if you say it live, it’s obvious whether or not you really mean it,” Giner-Sorolla says.

Rod Gamble’s father died of a heart attack at 59, and there were signs that Rod too might not live to see old age when he developed life-threatening cardiac rhythm problems in his early sixties. But thanks to ever-improving heart treatments, the retired parcel distribution company manager from Scunthorpe in the United Kingdom is still fit and active at 72.

After the self-declared “sports fanatic” collapsed twice while playing golf in 2008, doctors diagnosed an abnormally slow heartbeat. They fitted him with a pacemaker that delivered electrical impulses to stimulate his heart to beat at a normal speed. Rod came to be totally reliant on the device, which sat just under the skin beneath his left collarbone with a wire leading through a blood vessel to the heart.

But the pacemaker was not without its problems. It had to be replaced after six weeks when the pacing wire moved, and then Rod developed an infection after the battery—worn out from being used at 100 per cent capacity to keep him alive—had to be replaced in September 2014.

“Early one Sunday morning I got up to go to the bathroom,” he remembers. “I felt something running down my chest.” To his horror he saw that the infection had split the pacemaker scar wide open, the wire was hanging out and pus was oozing out of an inch-wide wound.

The infection meant that a simple replacement was out of the question but in June 2015 a new kind of pacemaker came to his rescue. The Micra Transcatheter Pacing System was the world’s smallest, a tenth of the size of a standard device, but, even better, it would be implanted into the heart itself, making it wireless and invisible. “When I saw it, I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “It was like a bullet with tiny hooks!”

Two years later, he plays golf most days, goes to the gym and is very thankful for medical advances. “All I want is to live as long as possible,” he says. “I’m thoroughly enjoying life.”

Heart disease is the number one killer in Europe. According to the most recent statistics from the European Heart Network, more than 85 million people were living with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in Europe in 2015 and it accounts for 45 per cent of all deaths in Europe.

But the trend is downward. Cardiovascular disease is no longer the main cause of mortality in Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom. In fact, annual deaths from cardiovascular disease in Europe are down from 4.3 million in 2008 to 3.9 million today.

Professor Mike Knapton, associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation, cites a number of reasons for this. “Levels of smoking have been reduced,” he says, “there have been some improvements in diet and physical activity, and high blood pressure and cholesterol are better managed.” More people also have rapid access to treatments at specialist cardiac centers.

Importantly, those treatments are more effective. Only 50 years ago, bed rest and morphine were the standard therapies for a heart attack—when blood flow to the heart is interrupted by a blockage, usually caused by a build-up of fatty material in the artery, causing damage to the heart muscle. Survival rates were low.

But now, as Professor Knapton explains, “Recent advances in the treatment and management of CVD to reduce mortality or improve quality of life have resulted in a useful range of interventions available to professions and patients.”

So what do today’s doctors have in their toolbox to mend broken hearts?

Drugs

Aside from drugs prescribed to cut the risk of heart attacks and stroke, such as statins for high cholesterol and anti-hypertensive medication for high blood pressure, a wide range of drug therapies are available to treat cardiovascular problems when they occur. These include thrombolysis for a heart attack (or a myocardial infarction, to give it its medical name). This involves injecting clot-busting medicine into an artery to dissolve a blood clot and restore the blood supply to the heart.

Meanwhile, a new treatment for heart failure—when the pumping action of the heart is inadequate—has been touted as a wonder drug. Every day 10,000 Europeans are diagnosed with heart failure and 15 million are thought to be living with the condition. There is a high risk of death within five years. However, in trials Entresto (sacubitril valsartan) was shown to reduce cardiovascular death by 20 per cent compared to the standard treatment, hospitalization for heart failure by 21 per cent, and death from any cause by 16 per cent.

“We have been able to show a rapid improvement in a few weeks in the condition of the patients treated,” confirms Dr. François Picard, a heart specialist from Bordeaux Hospital, France.

Angioplasty and stenting

To re-open an acutely blocked artery that has caused a heart attack, you may receive clot-busting drugs or undergo an angioplasty, or both. Angioplasty involves tracing a catheter up an artery in a leg or arm to open up constricted coronary arteries under local anesthetic and then inflating a tiny balloon to push back the blockage against the artery wall. In addition to its use in treating acute heart attacks, angioplasty is also used to relieve stable angina symptoms—chest pain brought on by activity or stress—that are caused by the narrowing of coronary arteries.

Germany has the highest rate of angioplasty procedures in the OECD. “It’s very clear from studies of more than 20 years ago that in patients with acute myocardial infarction you reduce mortality, improve survival and also prevent heart failure by this rapid re-opening of the artery with a catheter,” says Professor Johann Bauersachs, director of the Department of Cardiology and Angiology at Hannover Medical School. Speedy intervention prevents damage. Without angioplasty, on the other hand, at least 20 to 30 per cent of people suffering a major heart attack would die, he says. “It is a very clear life-saving therapy.”

Sometimes one or more stents—a small stainless steel mesh tube—are inserted to keep the blood vessel open. These have improved markedly. The bare-metal stents of the 1990s led to re-narrowing of the artery in 30 per cent of cases. “Since 2005 we have had several generations of drug-eluting [drug-coated or medicated] stents that secrete a special substance that prevents re-occlusion,” says Bauersachs. These have brought the rate of re-stenosis down to 5 to 10 per cent. “The problem of coronary artery disease is mostly solved with these really very safe and effective drug-eluting stents.”

Petr Rehousek, an orthopedic surgeon from Cˇeské Bude˘jovice, Czech Republic, is a living testament to the effectiveness of angioplasty and stenting. In 1996 at age 51, he had pain in his chest while cutting the grass and was diagnosed with a heart attack. After being given thrombolytic drugs, Petr was airlifted 150 kilometers to a hospital in Prague for an angioplasty. During the procedure doctors placed two stents in one artery. Since then he has had a further four angioplasties and five stents to treat narrowing in other arteries.

He finds the procedure itself uncomfortable. “When they put the catheter in, they block the artery for a short time and you have pain and feel pressure in your chest,” he says. But it has made a lasting difference to his quality of life. “I can take part in sports in the same way as before and in the same way as people who haven’t had angioplasty,” says. He still works as a doctor, cycles to work and last winter was winning ski races in his age group.

Pacemakers

These life-saving electrical devices have been used to treat heart rhythm problems since the 1960s. Standard pacemakers only treat a slow heart rate, while implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) can also deliver an electric shock to restore a normal heart rhythm for people with a life-threatening heart rhythm disturbance, such as a very rapid heart rate.

Smaller than a matchbox, the device is implanted under the skin on the chest under local anesthetic and the wires guided to the heart via a vein. However, the new, smaller wireless pacemakers, such as the Micra, are introduced through a catheter via a vein in the leg and threaded up to the heart. “Aside from the slight pain from puncturing the vein and insertion of the delivery system, there is no pain or discomfort,” says Dr. Jens Brock Johansen of the cardiology department at Odense University Hospital, Denmark.

Valve replacement

Rob Hackwill, 58, was born with a narrow aorta, the body’s main artery. When he was 13, doctors said there was nothing further they could do to fix his heart. “It worked very hard to push blood through a hole that was too small,” explains Rob. “My heart was always racing.” He grew into a pale, thin adult. In 2001 he was told that his heart was dangerously enlarged and he was in imminent danger of a heart attack.

But the Lyon, France-based journalist was relieved to find that cardiac medicine had moved on in leaps and bounds since his childhood. Within weeks, he had open-heart surgery to implant a new heart valve made of plastic, which, with the help of blood-thinning drugs, should last him the rest of his life. “I had color in my cheeks for the first time,” says Rob. He now leads a normal life and earlier this year became a father for the fourth time.

“The symptoms for someone who is distressed and disabled by a damaged aortic valve will considerably improve with aortic valve replacement,” says Professor Knapton of the British Heart Foundation. These days it can be undertaken with much less invasive operations, avoiding open heart surgery.

In transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), a valve is usually inserted under local anesthetic through a catheter in an artery from the groin or via an incision in the chest wall. It is especially suited to elderly or very sick patients who are too frail for more invasive surgery. As with an angioplasty, a balloon is inflated in the heart and a new valve is then positioned. Valves are often made of animal tissue and don’t require anti-coagulant drugs, but they don’t last as long as Rob Hackwill’s composite valve.

In Germany TAVI is more common than open-heart surgery. It is often used to treat aortic stenosis—narrowing of the aortic valve—which affects one in ten people over the age of 80. “It is so easy to perform now and so safe,” says Hannover cardiologist Johann Bauersachs, whose oldest TAVI patient was 97. “With TAVI, a patient is able to get out of bed the next day and they stay in hospital five to seven days.” This compares to weeks of hospitalization and rehabilitation after open-heart surgery.

Catheter ablation

Catheter ablation is used to treat heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmia) using fine wires threaded into the heart through blood vessels to burn or freeze small areas and create a scar that blocks abnormal electrical signals. It is used on people with atrial fibrillation (AF)—a heart rhythm disorder that can cause stroke or coronary heart disease—whose heart rhythm remains abnormal in spite of drug treatment. There will be an estimated 14 to 17 million patients with AF in the European Union by 2030, with 120,000 to 215,000 new cases diagnosed each year. They often suffer debilitating palpitations, shortness of breath, tiredness, weakness and depression. But over half of people who have catheter ablation have no further symptoms.

Electric cardioversion

For Amsterdam resident Patricia Vlasman, however, ablation was not able to bring permanent relief for her atrial fibrillation, caused by a serious congenital heart problem. The 46-year-old, who was born with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy—in which the myocardium, the muscular wall of the heart, thickens and stiffens—has also had “all the medications possible” and a pacemaker. Patricia, author of Open-hearted—My Life with Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure, finds that only electrical cardioversion helps restore normal heart rhythm.

Under short-acting general anesthetic or sedation, medical staff give electric shocks using electrodes attached to large sticky pads placed on the chest and connected to a defibrillator machine. “After cardioversion my chest becomes calm again and that is such a relief,” says the Dutch mother of one who suffers nausea, dizziness, breathlessness and a rapidly beating heart when she has arrhythmia. “Just to breathe again, full to your belly, inhaling the air, that is awesome.”

However, the treatment is only a short-term solution for Patricia. She has had 103 cardioversions and doctors have now put her on the waiting list for a heart transplant. Around 2,000 Europeans receive a new heart every year and half will live for ten years or more, with some patients living more than 25 years after the transplant.

Vlasman knows she owes much to new drugs and techniques, and the skill of doctors. “I’m lucky that I’ve been able to live longer and see my son growing up,” she says. “I realize this every day and it makes me grateful.”

The Future of Heart Medicine

New heart treatments are in development. Among the most promising:

Regenerative medicine. In the future, stem cells could be used to repair damage to the heart muscle. At present, this damage cannot be reversed.

Genetic diagnosis and stratified medicine. By identifying gene mutations that cause premature heart disease and death, early treatment can be offered. Treatments can be targeted to patients.

Technology. Advances in wearable technology allow more monitoring out of hospital, and enable patients to take charge of their condition.

Jump for joy

Achievement Verdun Hayes had wanted to take a parachute jump for a decade when he finally took the plunge (literally) last year. Nothing unusual in that—we often take time before getting round to fulfilling our dreams. But what makes Verdun a little different is that he first had the idea of leaping out of a plane at the age of 90, and his first jump, at the age of 100, made the former Second World War army lance-corporal from the county of Devon the UK’s oldest skydiver.

But that wasn’t enough for Verdun. This summer he took to the skies again and became the oldest person in the world to skydive, at the age of 101 years and 38 days. His tandem jump from 15,000ft was accompanied by three generations of his family. As he landed, the intrepid centenarian said “hooray” and announced that he was “over the moon”.

The jump raised money for the Royal British Legion, which provides support for the UK’s armed forces community. Its spokesman said the organization was “very proud of Verdun’s achievements”.

Electric ship will sail itself

Transport We’ve all heard of self-driving cars, but how about self-sailing ships? Two Norwegian companies aim to launch the world’s first autonomous and electric-powered cargo ship next year, saving 40,000 lorry journeys a year.

The Yara Birkeland will be able to carry around 100 containers at a speed of 12 to 15 knots. It will have a range of 65 nautical miles, enabling it to transport fertilizer between three ports in southern Norway. Although it will initially be manned, remote operation is scheduled for 2019, with fully autonomous operation in 2020.

“With this new container vessel we reduce noise and dust emissions, improve the safety of local roads, and reduce NOx and CO2 emissions,” says Svein Tore Holsether, chief executive of the fertilizer company.

Worms wage war on plastic

Environment A chance observation that the larvae of wax moths were able to eat their way out of a plastic bag has led scientists in Spain and the UK to believe they may have found a solution to the huge amounts of plastic waste accumulating in landfill sites.

The next step is to find out whether the worms were eating the plastic for food or just as a means to escape.

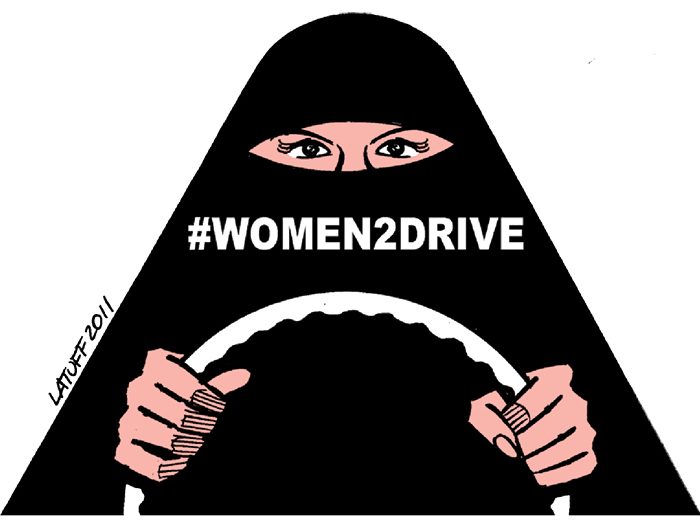

Saudi woman defies driving ban

Heroes After continuing protests from campaigners around the world, Saudi Arabia last month finally announced an end to its ban on women drivers from June next year. One of those who helped secure the change by defying the ban, risking arrest and punishment, was university student Ashwaq al-Shamri who earlier this year jumped behind the wheel when the driver of her bus suffered a stroke.

“He told us that he felt dizzy and then suddenly stopped,” she says. “My colleagues tried to give him first aid and I drove to the nearest shop to get him cold water.” Ashwaq, who was taught to drive at a young age by her father to help with work on their farm, then drove the stricken driver to his house, so relatives could rush him to hospital in time for him to make a full recovery. “I am extremely proud of my daughter,” says Ashwaq’s father.

Sources: Achievement: The Guardian, 14.5.17. Transport: The Local (Norway), 10.5.17. Environment: The Guardian, 25.4.17. Heroes: The New Arab, 12.5.17

If belly pooch is your biggest enemy when it comes to weight loss, you’re certainly not alone. While it would be great to just wave a magic wand and make the flab disappear, there’s actually something that comes pretty close: exercise. One exercise in particular is scientifically proven to whittle your waistline—and make your belly fat practically vanish into thin air. (This is the absolute best way to build muscle, according to science.)

A study published in the Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness has recently revealed the best way to flatten your stomach. Over the course of eight weeks, 39 volunteers exercised four times per week. While one group performed four regular cardio and strength workouts, the other group did two regular workouts and two high-intensity interval training (HIIT) workouts. Then, researchers used a series of tests to assess the participants’ progress.

The final results couldn’t have been more clear: Not only did the HIIT group lose more weight overall, but they also lost more inches to their waistline when compared to the conventional exercise group. The HIIT participants also significantly reduced their levels of visceral fat, which is found in your abdomen and associated with health problems such as type 2 diabetes. What’s more, the HIIT group also showed an increase in their cardio respiratory fitness, while their counterparts did not. (Your home is filled with free fitness equipment, like these household items.)

Thanks to the short, intense bursts of energy required for HIIT workouts, your body gets pushed to its absolute limit, causing it to burn fat for the rest of the day, researcher say. Four of these training sessions per week could be the secret to getting the six-pack you’ve always dreamed of. (Ready to get started? These simple exercises can flatten your belly without a single crunch.)

If you don’t have a gym membership yet, you can still banish your belly fat for good. Just focus on your plate, instead. These six foods fight belly fat; incorporate them into your diet, and you’ll be on your way to a slimmer waistline in no time.

Fitness blogger Katie Dunlop melted off 45 extra pounds in a sustainable, healthy and fun way. Here’s how you can too.