The reason why I choose to celebrate Canada 150

The Aboriginal community had been exploited for generations: treaties not lived up to, countless agreements signed in bad faith, and lands misappropriated, exploited and stripped of all its natural resources. The corporations and governments involved did nothing positive for the Aboriginal communities, but they did manage to leave behind a wave of environmental nightmares and displaced people.

Then, there’s the residential schools scandal.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission figured at least 4,000 Aboriginal children died. Ask yourself, “How did this happen?” Was it the fault of the average Canadian living back in the day? Racism has always been around, and sadly it will never disappear. I believe the residential schools scandal happened because of the government of that time. It was a political system geared to the exploitation of minorities and working poor. The government only cared about their political and economic agendas, and it was the Aboriginal communities that paid the ultimate price.

As for the government saying sorry? It’s never enough for the victims of government. Compensation? No amount of money can compensate an individual for having their culture stripped away from them or living with the knowledge that their child was abused, mistreated and died at the hands of others who were paid to protect them.

Canadian history is blanketed with policies and events that have scarred the Aboriginal community. So, as an Aboriginal artist, I asked myself. “Why would I celebrate Canada’s 150th?”

Many in the Aboriginal community have expressed their desire to boycott the celebrations, or will refuse to sing “O Canada.” I have no problem with that. As a free society, we all have that right—a right that was protected by the blood and sacrifices of others. A right that has been re-enforced by generations of protesters demanding that our government come clean on issues.

After a lot of deep thought and reflection, I decided that on a personal level, I would celebrate Canada’s 150th. Here’s why:

Canada Day for me is an opportunity to celebrate the lives of others. People who touched my life directly and indirectly. Uncles who fought and died overseas, family and loved ones who are no longer here. To me, they are the ones who made Canada great. It is their gift to us, their ongoing legacy. It’s also an opportunity to make fellow Canadians aware of issues and to acknowledge the achievements of all Aboriginal peoples. To acknowledge individuals who worked hard to promote change, peace and understanding of our culture in a positive light.

Tom Longboat from Six Nations Indian reserve near Brantford, Ont., ran the 1907 Boston Marathon four minutes and 59 seconds faster than any one of the previous winners. Two years later, he won the title of Professional Champion of the World. June 4th was officially declared Tom Longboat Day in Ontario with the passage of Bill 120, a Private Member’s Bill forwarded by Liberal MPP, Mike Colle.

Ianis Obomsawin: a documentary filmmaker whose more than 40 films have chronicled Indigenous life in Canada.

Rosemarie Kuptana (Inuit): a tireless leader of human rights. Kuptana served as the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation president from 1983 to 1988, where she was instrumental in developing it to express and reflect Inuit culture and society. She was elected to a three-year term as president for the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada in 1991, the national voice of 35,000 Inuit people.

Chief Dan George: a poet, actor and activist. George was the first Aboriginal person that people saw on TV and in movies, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Little Big Man.

These are only a few examples of individuals who have made a difference in the lives of all Canadians.

The Aboriginal community has a proud heritage. They have survived generations of discrimination and exploitation, and I take great pride in the knowledge that they still continue the fight. For me, celebrating Canada Day is not about the nation. It’s about the individuals that make Canada what it is.

I know there are a lot of people out there like me, with conflicting feelings about patriotism. We need to remember and educate others about the past, but also be a part of the evolving society around us, making today and tomorrow better for our people and all people. You can either decide to be a part of something, or just apart.

Happy Canada Day!

Fifty years later, Expo 67 is still unforgettable

As we begin to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday, I still remember 1967—Canada’s 100th birthday. There were parades and Bobby Gimby’s song “CA-NA-DA,” and people and towns were encouraged to create a Centennial Project.

I collected Centennial coins and still have one of the dollar bills that doesn’t have the flag on top of the Parliament Buildings. One of the other things I kept from that year was a scrapbook.

In January 1967, I was in Grade 6. My teacher, Mrs. Peever, handed me a scrapbook. I am sure that scrapbooks were given out to many schoolchildren in Canada in an effort to get them involved in the Centennial celebrations. It contained maps and historical facts about Canada and, of course, empty pages to be filled. This scrapbook was a project to be completed and graded at the end of the year.

In July, my parents, older brother and I took a bus trip to Expo 67 in Montreal. It was a very quick trip. Early one morning, we boarded Fowlers Bus in Bancroft, Ont., and off we went to Montreal, where we stayed overnight and then came back very late the next day. Basically we only had parts of two days to enjoy the spectacle that was Expo 67.

We visited the British, Russian and Canadian pavilions, among others. We also rode the monorail and walked and walked and walked. I remember my father wore a suit—he must have been so hot! Mom had wisely brought an insulated bag full of drinks and snacks and my brother had to carry the bag all over Expo. I collected any and all things that were Centennial related.

When I got home, I pasted the brochures and picture books that I’d picked up into my scrapbook. The blurry black-and-white photos that I took at Expo 67 made the book feel a bit more personal. I then filled it out with articles that I cut from newspapers and anything that I thought was interesting and pertained to Canada’s 100th birthday.

Back at school, late in the fall and now in Grade 7, I handed my scrapbook in. For my year-long efforts, Mrs. Peever graded my project as “good.”

I hadn’t looked at that scrapbook for more than 45 years, but when I dug it out of the trunk and started flipping through it, memories of a wonderful year flooded back—really good memories!

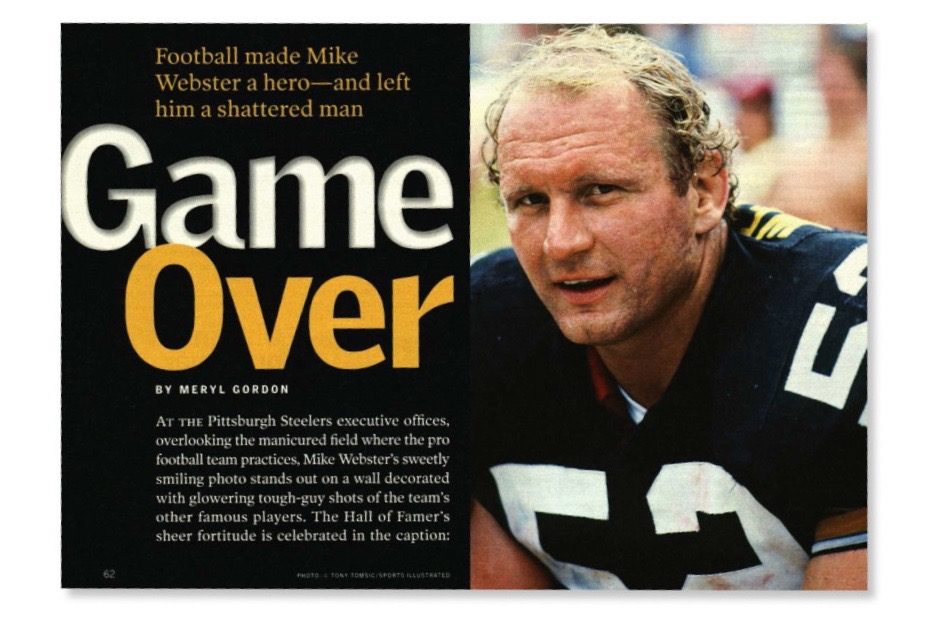

In Will Smith’s 2015 movie Concussion, the actor portrays the pathologist Bennet Omalu, who first revealed proof of football’s deleterious effects on players’ brains and published breakthrough papers in medical journals on the degenerative brain disease he discovered, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. Pittsburgh Steeler centre Mike Webster was the first NFL player Omalu autopsied.

In its March 2003 issue, Reader’s Digest wrote about Webster’s shattered life. Our piece addressed the role that the thousands of concussions Webster sustained during his football career affected his brain and contributed to his death in 2002 at age 50. The article is published in its entirety below.

At the Pittsburgh Steelers executive offices, overlooking the manicured field where the pro football team practices, Mike Webster’s sweetly smiling photo stands out on a wall decorated with glowering tough-guy shots of the team’s other famous players. The Hall of Famer’s sheer fortitude is celebrated in the caption: Webster “played the most seasons (15) and games (220) in Steeler history.”

But in Webster’s rented town house in the Pittsburgh suburb of Moon Township, his family has kept a much sadder tribute—a sheaf of Webster’s scribbled notes torn from a legal pad, page after page of heartbreaking gibberish, the legacy of a brain injury sustained while playing centre for the Steelers. His anguish is evident as he writes about his mental state: “…deep, confusing, twisting fishing line tangled up mess of confusing things go on all the time.”

Mike Webster died of a heart attack at age 50 on Sep. 24, 2002, at a Pittsburgh hospital. This undersized six-foot-two athlete, who through force of will turned himself into “Iron Mike,” led a life of extraordinary career highs—followed by a slowly devastating decline.

The years of being butted repeatedly on the head took a brutal toll. An avid reader, Webster could still devour books on Winston Churchill and World War II, yet his memory was so fragmented he couldn’t remember the simplest things, sometimes sleeping in his car by the side of the road because he didn’t know how to get home.

In October 1999, Webster was awarded an NFL disability for traumatic brain injury. His story, however, isn’t just a cautionary tale about gridiron injuries. It’s a saga about a man who was loved deeply by family and friends, but who lost the relationships he prized most. A man who, despite his anger at his own fate, was nonetheless trying at the end of his life to teach his beloved sport to a football-crazy son. A man whose disturbing end has left his former teammates with questions that will forever haunt them.

Mike Webster grew up on a potato farm near Tomahawk, Wisconsin, where rooting for the Green Bay Packers was a religion. Even as a young boy, he saw that sports was a small-town way to shine. The second of six children, he didn’t have an easy childhood: His parents divorced when he was ten, and a year later his home burned down, with Mike, his mother and siblings barely escaping the inferno. In high school, Webster moved in with his dad, and went out for wrestling, then football. “He couldn’t sleep the night before a game, he was so wound up,” says Bill Webster, Mike’s father. “I don’t think he cared about being a hero, he just liked the game.”

While at the University of Wisconsin on a football scholarship, he met his future wife, Pamela, who worked in the athletic department ticket office. “He had such kindness in his heart,” she recalls. “He’d open doors for me, he’d call when he said he’d call. And he had such a soft spot for children.” The couple married shortly after the Steelers drafted him in the fifth round in 1974, and eventually had four children: Brooke, now 26, sons Colin and Garrett—24 and 19—and Hillary, 15.

Grateful to be playing in the big time, Webster overcompensated for his size by becoming the hardest-working, play-with-pain member of the team. “Mike would be the first one at the stadium and the last to leave, he was so afraid to fail,” recalls Pamela. “Even on vacations, he’d pack the football ‘sled’ and push it across a field.”

Webster’s former teammates remember him as a quiet, determined man who seemed blessed with a photographic memory—and who studied the game as if every play depended on him. “You look at the centre position as the foundation,” says legendary running back Franco Harris. “Mike was a guy you could always count on.”

He also relished his indestructible image. On one occasion, Webster showed up at a game on crutches, with torn cartilage in his knee, played anyway and had surgery afterward. His toughness made him a winner: He was voted onto the All-Pro team six straight years, won four Super Bowl rings, and joined the greatest players ever in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

But play after play, year after year, Webster slammed into much bigger players, their helmets crashing into his like battering rams, their forearms pounding his head. And the beating left its own legacy. “He got his bell rung all the time, just like the rest of us,” says former teammate Rocky Bleier.

Also like the others, he tried to shrug it off. “Everybody gets injured, but most injuries aren’t reported,” says Miki Yaras-Davis, director of benefits at the NFL Players Association. Players worry about ending their career, she says. “Some of the guys will treat a concussion like a hangnail.”

Webster was never officially treated for a concussion—“He never complained about anything like this,” says Ralph Berlin, the Steelers trainer during Webster’s playing years. But doctors say he suffered multiple concussions, among his many other injuries, on his way to gridiron glory.

Soon after his last season in 1990, Webster moved, at his wife’s urging, back to her hometown of Lodi, Wisconsin. That’s when, as Pamela says, “Mike changed.” He seemed physically disoriented and started to behave strangely. Webster had always handled their financial affairs, so his wife was startled to discover that he wasn’t opening mail, or paying bills, or even filing taxes. This reliable family man who used to read his children Bible stories at bedtime began to get in his car and disappear for days. “I didn’t realize he had a brain injury,” says Pamela. “I just thought he was angry at me all the time.”

Money quickly became a problem. Webster had several million dollars in assets when he retired, so it shocked Pamela when their Victorian house was foreclosed 18 months after he left football. Webster’s finances remain a muddle, but from conversations with his family and lawyers, it appears he poured most of his savings into investments that went bad.

The financial strain couldn’t fully explain his increasingly bizarre behaviour, however. Pamela put up with it for a while, but the couple separated for the first time around 1992 (she finally divorced a reluctant Webster last March after years of living apart).

Meanwhile, Mike began drifting back to Pittsburgh, spending more and more time there. Former colleagues soon began to hear disturbing stories about him, but no one knew what was wrong, and Webster was mystified and frustrated himself, embarrassed that he couldn’t seem to hold a job or even remember scheduled meetings.

The Steelers’ now-retired public-relations man Joe Gordon says, “I got a call from the manager of the Amtrak station, saying Mike is here and he slept here last night.” Gordon found Webster there, poring over brochures and talking excitedly about a plan to market celebrity photos—“This could be big”—but he had no place to sleep. At the team’s expense, Webster was put up for six weeks at the Pittsburgh Hilton, before decamping to a $25-a-night joint.

Too proud to ask his teammates for help, Webster was eventually befriended by a fan, Sunny Jani, who sought Mike out after reading about his troubles in the newspaper. “He was my hero,” says Jani, who owns a grocery store and sports-memorabilia shop. Jani began to handle the increasingly frequent crises, bailing Webster out of awkward jams. “Mike would call at 2 a.m. and say he’s lost.” Webster saw a slew of doctors during this period in the mid-’90s, including one who told him he appeared to be brain-damaged. “Have you ever been in a car accident?” the doctor asked.

“I’ve been in 350,000 car accidents,” Mike replied. Some half-dozen times Webster requested an application for disability payments from the NFL, but he never followed through.

By the time Webster entered the Hall of Fame in July 1997, he had become a recluse, in agony from herniated discs and hand injuries, impoverished and angry at his fate. He put on a brave front, though, for his two daughters. His youngest child, Hillary, who was living in Wisconsin with her mother, says that in recent years, “My father called me every night.” But his two sons, who lived with him at different times, saw a more tortured side. Colin remembers that his father was shaking so much from his condition that his desperate solution was to buy a police Taser gun. “He’d zap himself to calm his nerves. He’d do it 10 or 20 times to relax.”

Webster was prescribed Ritalin to control his mood swings, but in 1999, shortly after his regular doctor moved away, the athlete was arrested for forging Ritalin prescriptions. He gave an emotional news conference apologizing for “any embarrassment and sadness” he’d caused, and was sentenced to probation. That same year, his lawyer, Robert Fitzsimmons, finally won Webster a $115,000 yearly payment from the NFL for a football-related disability. (That payout ended with his death, but his two youngest children now receive $1,500 a month each.)

“He wanted to provide support for his family,” says Fitzsimmons, who pulled together a raft of supporting medical records, and brought in a psychologist from Marshall University Graduate College, Fred Jay Krieg, to examine Webster.

“Mike had dementia due to head trauma, a series of blows to the head over a period of time,” Krieg says. “He couldn’t concentrate, he had difficulty focusing, the conversation was rambling.” Krieg adds there was no other explanation for Webster’s deterioration; the repeated banging of his brain against his skull had damaged the brain’s nerve cells.

Since Webster was so passionate about football, it was painful for him to accept that the sport had left him permanently impaired. It was too late to undo the harm, however, just as it was too late to dissuade his son Garrett from playing. “When I was young, he said he wanted me to be somebody, like a lawyer,” says Garrett, who moved in with his father three years ago. But the towering six-foot-nine, 340-pound teenager figured he was built for the game, and made it clear to his father he was going ahead with or without help. So Webster launched a single-minded coaching clinic. He taught his son plays, watched game tapes with him, even tried to run with him despite knee and back injuries. Mike was also on the sidelines at every game. “He tried to stay low-key,” says Moon Area High School’s football coach Mark Capuano. “He preferred it if people didn’t recognize him.”

The last year of Webster’s life brought new woes: His divorce became final, his health worsened and his finances collapsed again. He had been receiving money from annuities and the disability payment—much of it went to alimony and child support—but the IRS then garnished almost all of his income for unpaid taxes. He and Garrett were ousted from their apartment for unpaid rent; Jani helped pay for a new place, but Webster couldn’t afford furniture. The father and son slept on the floor, surrounded by pizza boxes. Often unable to pay for medicine, Webster would shake so hard he couldn’t drive his son to school. “I couldn’t leave him in that situation,” Garrett recalls. “I had to be the dad sometimes.”

On a Friday night this past September, Webster went to his son’s football game. But as the weekend progressed he complained of feeling ghastly. “He woke up Sunday morning, his lips were purple, he was sheet white,” says Garrett. But Webster refused his panicked son’s entreaties to go to a hospital, in part because he didn’t have insurance. Finally, later that night he let Jani drive him there; doctors said he’d had a heart attack. Garrett was with his father when he went into a coma and then passed away on Tuesday: “I took it hard when they told me he was going to die. But when he died, I felt this calm come over me. I could feel a pat on my shoulder, almost a whisper in my ear, ‘Everything’s going to be all right.’”

On a chill afternoon in November, Steelers owner Dan Rooney sits in his office, fondly recalling Iron Mike. “He’d cut off his sleeves in the freezing cold, zero degrees, to intimidate the other teams,” Rooney says with a grin. Over the years he picked up expenses for the financially beleaguered Webster and even paid for almost all of his $7,600 funeral. But Rooney refuses to believe Webster’s problems were more than psychological or that he was truly entitled to an NFL disability. “Everybody gets hurt in football,” he says, “but very few players get hurt permanently. He wasn’t eligible, to be honest. But we did get it for him.”

Midway through our interview, Rooney jumps up and strides out into the hallway to give a warm “Welcome back, how are you?” to Steelers quarterback Tommy Maddox. Three days earlier Maddox had suffered such a serious concussion during a game that he was temporarily paralyzed. “I’m feeling good,” the quarterback says, moving stiffly. An hour later, standing on the sidelines watching practice, Maddox complains to me: “I’m really upset that they won’t let me play.”

This from a man who 72 hours earlier didn’t know if he’d ever walk again. But then, Maddox wasn’t there at Mike Webster’s funeral. Grieving teammates were, and they felt shaken by this glimpse of their own mortality. “All these guys were talking at the funeral about maybe they should get checkups,” says Franco Harris.

The weekend of the funeral, Harris went to see Garrett Webster play football and was impressed by the teenager’s potential. But Harris thinks about the risks that Mike’s son will face. “A lot of guys look back, and they love the game,” says Harris. “But there are some who can’t walk, who find it hard to do simple things. You can’t help but wonder, is it worth it?”

Here’s why the Swedes have a six-hour workday

Have you ever caught yourself watching the clock while on the job? Do the hours seem to drag by as you sit at your office desk?

First of all, it could be a sign that you’re in the wrong career. But another culprit could be the long hours you’re spending in the office, experts say. Turns out, long working hours actually backfire for employees, making them less productive. Inc.com reports that over the course of an eight-hour workday, employees are only productive for about three hours, on average. (Here are the signs you might be burnt out.) On the other hand, employees who crunch their working hours tend to get more done—plus, they receive loads of other health perks.

Not convinced? Just ask Sweden! Companies in this Scandinavian country are beginning to scale back the length of the day, opting for a six-hour workday, Fast Company reports. And the results have been overwhelmingly positive so far. For Linus Feldt, CEO of Stockholm-based app developer Filimundus, the incentive to change came from his own experience.

“I think the eight-hour workday is not as effective as one would think,” he said. “To stay focused on a specific work task for eight hours is a huge challenge…In order to cope, we mix in things and pauses to make the workday more endurable. At the same time, we are having it hard to manage our private life outside of work. We want to spend more time with our families, we want to learn new things or exercise more. I wanted to see if there could be a way to mix these things.”

When Filimundus switched his company to a six-hour workday last year, he was immediately impressed. Not only were his employees focusing more intensely on their work, but company morale surged.

His employees “were happy leaving the office and happy coming back the next day,” Feldt said. “They didn’t feel drained or fatigued. That has also helped the work groups to work better together now, when we see less conflicts and arguments. People are happier.”

Swedish companies also believe that shorter workdays are an investment in their employees’ private lives. According to the CEO of Brath, another tech startup, “We believe that this is a good reason to stay with us and not only because of the actual impact longer hours would make in your life but for the reason behind our shorter days…we actually care about our employees.”

Still, despite the benefits, it’s understandable if you still want to stick with your 9-to-5 routine. (The Canadian work ethic often demands it!)

15 Minutes with Peter Mansbridge

Reader’s Digest: Looking back, 2015 was a pretty huge year for news. Did it feel that way for you?

Peter Mansbridge: It was well-rounded. You had the war stories with Syria and Iraq and the emotional reaction to the refugees, which connected with people all over the world. Domestically, you had the election, which we knew was going to be big, but then it was much bigger than we’d anticipated. A change of government, a new leader who is young and engaged…

And also very handsome.

Ha! He seems to have that going for him.

This month you have a cameo in Disney’s Zootopia, voicing a moose named Peter Moosebridge. How did that come about?

I got started in this business at age 19. I was working at an airport, and someone heard my voice over the PA system and offered me a job at the local radio station. With this film, I was at an airport once again. I was going through security in Toronto on my way to Vancouver, and the guy behind me said, “We were just talking about you in a meeting!” Turns out, he was the Canadian vice-president of marketing at Disney. Zootopia is a children’s movie with a good message about fairness and equality. I only have two or three lines. I was excited to do it for my grandkids.

Last year you appeared on an episode of Murdoch Mysteries. Has Canada’s most venerable newsman caught the acting bug?

No, no. I’m married to an actor. I think she’s kind of jealous that I have a part in what will be a huge film—I feel it could be the next Frozen. When I came home and told that to my wife [Cynthia Dale], she was not impressed.

During times of upheaval, do you miss hopping on a plane and going to the story?

I still go on the road as often as I can. I was in Paris right after the attacks. Part of me loves that. I was a reporter for 20 years. I was okay, but I wasn’t great. I understand where I’m best used. It’s like a good hockey team, where the coach and the manager know where to put their players.

When you were inducted into the Canadian News Hall of Fame last November, you said that public broadcasting isn’t about being popular, it’s about being relevant. Can you explain that distinction?

Newscasters are constantly tempted to cover what’s popular—water-cooler stories and all that. The public broadcaster is there to deal with what’s important. There are things about the day that are funny—you don’t want to give viewers the sense the world is going to end when the newscast does—but it’s a question of where you dwell.

How do you feel when you see someone in the vein of Kim Kardashian being described as a newsmaker?

Let’s put it this way: she’s never been a newsmaker on my program.

So it’s safe to say we won’t see you sitting down with a reality TV star any time soon?

I don’t think so. I’d like to interview Justin Bieber. We’re both from Stratford, Ont. He comes home a lot more than most people realize. You hear his jet—it’s the only jet that comes into the Stratford airport.

Here’s why Millennials are the happiest generation ever

Think the avocado toast joke has gotten old? You’re not alone. Truth is, it’s time to start paying less attention to how millennials save their money and pay more attention to how they spend it, instead. Doing so may reveal why millennials are the happiest generation—like, ever.

Their secret? Taking care of themselves. And that goes for mind, body, and spirit, experts say.

According to NPR, “more millennials reported making personal improvement commitments than any generation before them. They spend twice as much as boomers on self-care essentials such as workout regimens, diet plans, life coaching, therapy, and apps to improve their personal well-being.” They also tend to spend their money on experiences rather than things, which research has shown makes people feel more satisfied and fulfilled.

Self-care is not a new concept (nor a hard one!), but it’s super effective. After all, you can’t help others until you can first help yourself, as the saying goes. Self-care is also a sign of emotional intelligence, or the ability to harness and manage emotions for thinking, problem solving, and “cheering up or calming down other people,” according to Psychology Today.

As a result, more millennials than ever report being happy. That’s especially true compared to the Baby Boomers, which the Pew Research Center labeled the “gloomy” generation. Baby Boomers tended to rate their overall quality of life much lower than non-boomers. Meanwhile, younger generations had a more positive outlook overall—most likely due to their lifestyle choices centered on individualized self-care.

So the next time someone makes you feel guilty for that luxurious mani-pedi, you finally have an excuse! Just remember that it’s all in the name of being a little nicer to yourself.

The three languages every child should be learning

Learning different languages can be wildly beneficial for children in terms of development and cultural exposure, but with so many languages to choose from, which is the best for your child? A new study has narrowed it down for you.

The Centre for Economics and Business Research and Opinion conducted the study in partnership with Heathrow Airport. Experts analyzed how language can impact children’s lives and the role it plays in everyday life. They also determined which ones tend to lead to the best career opportunities as an adult.

“We believe that language learning is hugely beneficial for children’s development and it’s a real investment for the future,” said Antonella Sorace, professor of developmental linguistics and director of bilingualism matters at Edinburgh University.

The study involved a survey of 2,001 parents with children under the age of 18, along with another survey of more than 500 business leaders.

So which languages took top spot? Results indicated that children should be learning French, German, and/or Mandarin if they want to be successful within the next 10 years and maximize their employability. Proficiency in a second language opens the door to new markets for businesses and allows them to create new relationships with prospective partners.

Aside from being able to speak another language, the academic and interpersonal skills that can be gained from learning a new language are important as well. “Children who are exposed to different languages become more aware of different cultures, other people, and other points of view. They also tend to be better than monolinguals at multitasking and are often more advanced readers,” said Sorace.

A vast majority of parents surveyed in this study (85 per cent) believe it is important for their children to learn a second language, and about one in four believe it will enhance their child’s career opportunities and boost employability. However, 45 per cent of parents surveyed admit that their child or children cannot speak a second language.

If you want your child to stand out from the crowd as first-time job hunters, brush up on the habits of emotionally intelligent people—and, of course, make sure they learn one of the three success languages!