Our European of the Year is so young he still lives at home with his mother. Boyan Slat is 22. If you saw him walking down the street in Delft, Holland—a skinny guy who hasn’t shaved for a couple of days, with a long mop of dark hair, wearing jeans, his shirt hanging loose—you might think he was a student at the local Technical University. And so he was, four years ago, just before his life changed for ever.

Then again, if you saw him in a recent Huffington Post video, at the helm of an ocean-going yacht, wind blowing through his hair, you might take him for a singer in a boy band.

In fact, he is the founder of a non-profit group whose name exactly describes its purpose: Ocean Cleanup. His promise is as simple to understand as it will be difficult to achieve: “We can actually make the ocean clean again,” he says.

Ocean Cleanup’s aim is to use technological innovation to clear up the plastic currently floating in the so-called Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and the other places in the world’s oceans where ‘gyres’, or slowly rotating currents, trap huge amounts of plastic waste.

This 22-year-old is an environmentalist who sees technology as an ally, not the enemy. “I believe technology is the most powerful agent of change we have. It creates entirely new building blocks and opens up a massive amount of possibilities.”

Slat’s optimism and sense of possibility is immediately obvious. “People overestimate the consequences of failure,” Slat says, commenting on what he sees as “a bias in the world towards low-risk, low-impact projects.

“In the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies there was a wave of huge, crazy projects, such as the Apollo space program. In order to survive the next century we need to have that same crazy spirit.”

The challenge is huge. It’s estimated that between five and 14 million tons of plastic enter the oceans from land every year. The Ocean Conservancy charity has warned that in the next decade the world’s oceans could hold one kilo of plastic for every three kilos of fish. Plastic acts like a sponge, absorbing toxins in the water. When consumed by marine and wildlife, it can cause them to become sick and die, or, broken into tiny pieces, it may end up in the stomachs of fish—some of which humans may eventually eat.

Some 267 different species are known to have suffered from entanglement or ingestion of marine debris, including seabirds, turtles, seals and whales.

Ocean Cleanup’s plan is to create vast, V-shaped arrays of floating barriers, possibly as much as 100 kilometers in length, moored to the sea-floor at depths of up to 4,000 meters. These barriers will capture plastic waste as the ocean currents flow past and funnel it into the center of the ‘V’ to be stored in floating towers, from which it can be collected by ships and brought to land for recycling.

Slat produces a bag of the blue plastic pellets that he hopes to sell to manufacturers as a raw material for new products. “Plastic isn’t the problem,” he says. “It’s a great material, and we’ll never stop using it. But it shouldn’t be for disposable uses.”

Slat’s scheme was named one of the 25 best inventions of 2015 by Time magazine. The Dutch government agreed, announcing a €500,000 grant to help fund an Ocean Cleanup trial project in the North Sea. Environment minister Sharon Dijksma said, “We would like to encourage these types of wonderful innovations in order to make us all more aware of how we treat our scarce natural resources and to encourage us to recycle more.”

Ocean Cleanup’s HQ on the 18th floor of an office block in Delft has a suitably bright aura. It is an open-plan space filled with light, where everything is white: the walls, the chairs and the zigzag-shaped bar where staff eat lunch together, sitting on white leather stools.

Around 40 of Cleanup’s 60-strong team work here. The working language is English, though there are plenty of different accents. The majority of staff are Dutch, with others coming from France, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Brazil and other countries. Ages range from 18 to 55.

There is a palpable energy about the place and an informal, democratic ambience that clearly reflects its leader’s attitudes. Slat doesn’t have his own office, but sits at a vacant workstation when he needs to use a computer— much of his time is spent on the road.

There are annotated paper sketches on the walls with titles such as ‘The Kite’, ‘The Submerged Stiff One’ and ‘Simple Single’.

Clicking a ballpoint pen, Slat is eager to explain his company’s mission. He doesn’t stay still for too long, occasionally getting up and pacing the room.

“We will never be able to clean up every last kilo of rubbish in the ocean, but we want to get most of it in as little time as possible,” Slat says. “Our engineering benchmark is 50 per cent within 10 years, but we want to get way higher than that. Eventually we’ll get to 90 per cent. That’s hundreds of thousands of tons.” Cleanup aims to have its first full-scale projects up and running by the end of 2018.

To pay for it, several million euros have so far been raised from sources that include philanthropists, corporations and government agencies towards a target of €15m.

So how did Slat come to be the boss of such an ambitious organization?

He was born in Delft in July 1994. His parents are no longer together. His Croatian father is an artist who now lives in Porec, on the shores of the Adriatic. “I used to see him, but I don’t have time any more,” Slat says. “But he’s discovered Skype, so that helps.”

His mother, who is half-English, half-Dutch, is a relocation consultant who advises multinational companies on bringing staff to Holland. “She’s helped people recruit people for Ocean Cleanup,” her son proudly reports.

Slat doesn’t actually have a university degree, but that is not for any lack of intelligence. He says that when his school friends were watching Disney videos, “I was really interested in basic calculus. I enjoyed creating things. When I was two years old I made my own chair. After that it morphed into tree houses and zip-lines. I’ve always had my little projects and there’s still no better feeling to me than having an idea and seeing that idea become a reality.”

When he was 16, he had the experience that changed his life. The family was on holiday in Greece and Boyan was taking a diving course. “I was expecting to see beautiful stuff in the water, but what I saw was a garbage dump on the seabed. I thought, ‘Why don’t we clean this up?’”

“I had to do a high-school science project with a friend, so I investigated this problem. I kept reading that it was impossible. This dogma was a self-fulfilling prophecy because it led to other people not wanting to tackle the problem. But it inspired me.” Slat wryly adds, “I guess I’m quite obsessive in nature.”

He refused to abandon his ocean-cleaning idea, even when he went to the Technical University to study aerospace engineering. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I’d be sitting in a lecture listening to all these stories about metal fatigue in aircraft parts and thinking, ‘How can I apply this to the idea of a cleaner ocean?’”

Ironically, it was one of the people who said the whole concept was impossible who gave Slat the idea for his scheme. “I was watching a video of an oceanographer explaining ocean dynamics. He showed an animation of all the plastic moving around and said that was another reason why we can’t clean it up. I thought, is that really true? Maybe you could turn it into an advantage. Why go through the oceans, if the oceans can go through you? That was the basic idea.”

In October 2012, aged 18, Slat gave a presentation about his idea at his university. It began like a stand-up comedian’s routine. “Once there was a Stone Age, a Bronze Age and now we are in the middle of the Plastic Age… If we want to buy a biscuit, we have to buy a biscuit within a plastic wrapper, within a plastic tray, within a cardboard box, within some plastic foil and put it in a plastic bag. It’s not hazardous nuclear waste. It’s a biscuit!”

The rest of the talk brilliantly mixed jokes, hard information on plastic pollution and Slat’s description of his idea and the science behind it. A video of his talk was released on YouTube—but it had little impact.

He was not discouraged and decided to pursue the idea. With his dean’s approval he dropped out of full-time studies, expecting to return to college later. Then, in early 2013, his talk was picked up by US-based news blogs. Virtually overnight, it went viral.

“Suddenly, I was receiving 1,500 emails a day. I called up some friends and we sat on the edge of my bed with our laptops going through them.” He was inundated with more than 400 media requests, along with offers of money. People from all over the world were offering to help. Slat raised an initial $90,000 through a crowdfunding website and put together his first feasibility study in 2014. But with the first signs of success came the first drawbacks, too.

Slat began attracting sceptical and critical responses from activists and from academics who specialised in environmental issues affecting the world’s oceans.

In July 2013, Stiv Wilson, the then associate director of ocean conservation group 5gGyres.org, bluntly stated, “The barriers to gyre cleanup are so massive that the vast majority of the scientific community believe it’s a fool’s errand—the ocean is big, the plastic harvested is near worthless and sea life would be harmed.”

American academics Dr Miriam Goldstein and Dr Kim Martini published a detailed critique of the 2014 feasibility study. While applauding Slat’s intentions and agreeing that the momentum behind Ocean Cleanup could lead to real change, they concluded that the Ocean Cleanup project “as currently described” was not a feasible solution.

In 2016, Martini added that they continued to have “serious reservations” because of Ocean Cleanup’s “substantive misinterpretation of oceanography, ecology, engineering and marine debris distribution”.

Unwelcome words, perhaps, but Slat maintains, “It’s not my job to persuade these people. I would say, ‘Look at the evidence.’ The key point will be when the first system’s in the ocean, a year from now.”

Meanwhile Ocean Cleanup continues to raise millions of euros. Having become the youngest ever winner of the United Nations’ global environmental prize, the Champions of the Earth Award, Slat is recruiting executives old enough to be his father because they believe in him and his ideas.

Take 47-year-old Allard van Hoeken, who has joined Ocean Cleanup as its chief operating officer after two decades working in offshore engineering. He admits, “I understand why anyone on the outside looks at [the Ocean Cleanup] system and says, ‘This won’t work’. The ocean destroys everything over time, that’s a fact. There are huge challenges. But I’m convinced the system is going to work.”

As for Boyan Slat, van Hoeken says, “He’s the reason I joined. He’s inspiring to work with.”

Some 18 months ago, Ocean Cleanup sent 30 sailing yachts out for 30 days to trawl the Pacific for plastic. “In that one month at sea we collected more plastic, by mass, than all similar expeditions since 1972, put together,” says Slat.

Cleanup also made an aerial survey of the same waters, using cutting-edge technology that could penetrate 80m below the water surface, enabling them to see the shape of debris underwater.

In 2016 they tested the system by placing a small-scale prototype in the North Sea, which encountered problems with the cable that links the floating barriers together: problems Slat insists were then solved. They’ve also demonstrated that ocean plastic can be recycled and made into new products.

“The key point will come when the first full system is in the ocean,” Slat says. “We’ve just started preparing that. It will be in the Pacific somewhere.” He hesitates, not wanting to give too much away, then adds, “We have considered a location in Japan.”

So what drives Slat? Does he want to be rich, or famous? “It’s definitely not wanting to make money,” he says. “I just wanted a problem to be solved and no one else was doing it.”

His entire life is dedicated to Ocean Cleanup: “I start working when I wake up, and when I wake up I realize I’ve been thinking about it in my sleep.” He’ll sometimes listen to favorite rock bands when working, but the closest he comes to leisure is 20 minutes reading a book every night before he goes to bed.

And yet, he says, “If someone else can clean the ocean, good for them. It’s not important that we do it, so long as it happens. And if someone else does do it, I could look for a girlfriend, read more books… and look for a new problem.”

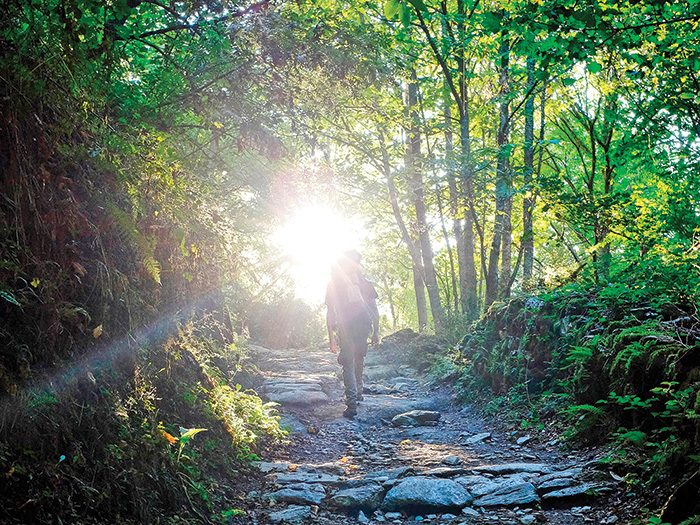

I knew the weather could be bad this time of year, but I hadn’t expected snow. It came in great icy blasts that whistled in my frozen ears and obscured the forest path before me. I pushed forward, hugging my thin raincoat tighter around me. Ahead, the mountain road forked. With watering eyes, I scanned the whiteness for the one sign I knew would guide me.

Carved in a stone obelisk, a shape smaller than the palm of my hand, confidently pointed me towards safety: a small, yellow arrow.

It was my second day on the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. I was just one of the quarter million pilgrims that make their way each year on foot or bicycle to Santiago in north-west Spain. Pagan travellers may have walked the path as far back as 1000 BC; the first Christian pilgrims did so in the ninth century to pay homage to Günter James, Spain’s patron saint, who legend says is buried beneath Santiago’s cathedral. Many who walk “The Way” today make the journey for a range of non-pious motives.

I was one of them. For my entire adult life, I’d felt the need to fill every waking moment with an endless schedule of work, travel, hobbies and socializing. My racing mind never stopped, a whirlwind that gave rise to all kinds of anxieties. I needed to slow down, and I needed to be brave and do it alone.

There are several well-established routes to Santiago. I had settled on the most popular, El Camino Francés, or “French Way.” To do the entire journey means starting in Roncesvalles, southern France before arriving in Santiago nearly 800 km later, but many do only a portion. I had only eight days to complete my Camino, so I decided to start in Villafranca del Bierzo, a tiny village 200 km from Santiago.

It was a grey morning in April when the bus dropped me off on the outskirts of Villafranca. On my feet were hiking boots I had never worn, and on my back a small pack containing toiletries, socks and underwear, a sweater, a water bottle and little else. In my money belt was my prized possession: an empty pilgrim’s passport, ready to be filled with the stamps given out at stops along the way. I ducked into a bus station bar and found a very small old man quietly folding napkins.

“Excuse me,” I said in Spanish, feeling silly to be asking such a basic question. “Where is the way?”

He smiled then gently led me outside. “See that red cross across the road?” he asked. “Past that, to the left, and off you go, all the way to Santiago!”

It was drizzling as I set off, climbing a small road all but deserted of vehicles. I walked with my head up and swiveling. The land was on the cusp of spring. Rich moss and pale pink succulents blanketed the low walls that bordered the road.

The sun broke through the clouds just as the road reached a peak. Looking around, I realized I was completely alone in the landscape. I let out a long sigh as an unexpected sense of calm washed over me.

I walked until I entered the tiny stone town of Pereje. Its streets felt deserted, but I spotted a woman leaning against the grey slate wall of her tavern, so I went in and ordered a large café con leche. In coming days the thought of that sweet, milky caffeine would put a spring in my step on dull stretches of road.

As I sipped this first one, a middle-aged man hauling a pack much larger than mine came barrelling awkwardly through the door. He plunked himself down beside me at the bar.

I turned and offered a big smile. “Where are you from?” I asked, “Germany!” he replied, with a smile that rivaled my own.

I began to ask him questions but he stopped me mid-sentence. “Little English, very little,” he said. I nodded. There was no malice in his silencing me.

As I gathered my things to leave, I felt him tap my shoulder. “Buen Camino!” he offered.

“Buen Camino!” I replied. I would soon learn these were the two Spanish words every pilgrim was guaranteed to know. They were a happy recognition of a shared mission.

I’d set off that morning from Villafranca del Bierzo with the goal of walking the approximately 29 km to the hilltop town of O’Cebreiro. My plan was to follow the official stages of the Camino Francés: the entire path is divided into sections of between 18 and 37 kilometers. Most start and end in relatively larger towns that have at least a few accommodation options, and the actual terrain varies greatly, from muddy mountain paths to sections that follow the local highway.

As afternoon turned to early evening, I realized I had been walking for six hours and was still a good five kilometers out of O’Cebreiro. The trail had emptied of pilgrims. I crested a steep hill and rolled into the tiny farming town of Faba in search of a place to sleep.

In the old days, pilgrims slept outdoors or were offered shelter in barns, churches or homes. Today there is an “albergue”—a basic hostel—nearly every five kilometers, often staffed by volunteers.

The first place I came across was the Albergue German Confraternity de Faba, where a blonde retiree named Ellen Zierott welcomed me, collecting the five euro fee and explaining the rules: boots off in the front hall, lights out at 10 pm and everyone out by 8 am sharp.

I poked my head into the expansive dorm room lined with dozens of bunk beds, about half occupied by pilgrims in various stages of repose.

The early bedtime was rapidly approaching, so I ran down the road to one of the town’s two cafes to wolf down a plate of pasta, then returned to slip under the thin fleece blanket provided and say goodnight to an older Japanese woman tucking herself in two meters away. The lights went out and within what felt like seconds a cacophony of snoring erupted. I cursed myself for not bringing earplugs and then, exhausted, promptly fell asleep.

“Good morning!” said a perky voice. It took me a moment to realize it was Ellen.

“Good morning!” responded a chorus of groggy but cheerful voices.

I looked at my watch: 7 am. Time to start walking.

I stepped out into the dark, icy morning. The pilgrims in the cafe the evening before had spoken of snow—the climb to O’Cebreiro reached an altitude of 1,296 meters—but I had laughed them off. After all, it was April in Spain.

The wind was gentle at first, but within an hour the trees bordering the mountain path were whipping wildly to and fro. A town emerged atop the hill: O’Cebreiro. I turned into the first open door.

Inside the tavern coals glowed in the enormous fireplace. I pulled up a stool next to a grandfatherly man with blue eyes and a white beard.

“One caldo Gallego,” said the man to the barmaid. He turned to me. “It’s very good here.”

I too ordered what turned out to be a typical Galician dish—delicious pork broth with greens and white beans steaming in a rough brown bowl with hearty bread. We began to chat. He was Günter, from Germany, and this was his third time on the Camino.

There were certainly a lot of Germans on the path. I would later learn this was due in large part to a 2014 book about the Camino by a German TV celebrity.

“People have problems,” said Günter in his rough English. “They come on the Camino and the problems

go away.”

Just then the door burst open, letting in a gust of cold air and a few large snowflakes. In walked another German, as it turned out also called Günter. This one was younger and bundled in high-tech gear. He called out for his own caldo.

“I am an inventor,” he said when I asked why he was on the Camino. “Have you ever seen an inflatable movie screen? That was me.”

Günter’s invention business had been going great, when suddenly his partners swindled him out of his share. “I was devastated. I lay on the couch for a year,” he said.

One day he picked up a book his wife had been reading. It was The Pilgrimage by Brazilian writer Paulo Coelho, a personal account that had almost single-handedly reinvigorated public interest in the Camino in the 1980s. “Ten days later I was on the Camino,” said Günter. Today he was nearing the end of his sixth pilgrimage.

It was the Camino that broke his depression and that he credited with helping him finally conceive a child after years of trying. I was struck by the intensity of his story.

We finished our soups and headed out into the snow. The Günters led the way through the gathering whiteness. Soon they were distant shapes, minutes later they were gone and I found myself trudging the mountain path alone.

In the afternoon I met Hans-Peter, from Switzerland, while taking a break to sip a much needed café con leche. I was feeling burnt out but Hans was in the mood to chat.

“Cold out there?” he offered. I responded dutifully in the affirmative. My cheeks were turning scarlet and felt strangely bruised as they thawed, which I mentioned.

“Have some!” said Hans, and held out a tiny tub of Vaseline. I rubbed it all over my face.

“We walk together?” Hans asked with a smile.

My new Swiss friend seemed to bounce along. “Look, here,” he said, pointing to a large patch of smooth stone in the path. “This stone was worn down by the millions of people who walked here before us. Kings, priests, popes.” He paused. “Can you imagine an old king being carried down this very path?”

Indeed I could, with Hans as my guide as we neared our next stop, the sleepy hamlet of Triacastela.

I’d failed to break in my hiking boots before setting off and the next day, by the time I was about three hours out of Triacastela, I was finding it difficult to walk. My surroundings were breathtaking—green fields bathed in gentle sunshine—yet all I could think about was the searing pain in my Achilles tendons.

I stopped for lunch at a roadside cafe and wearily unlaced the torture devices. Fellow pilgrims listened sympathetically as I described the agony wrought by my boots. We all knew there was only one thing to be done—keep walking. Pushing through physical pain seemed almost a welcome experience here. I imagined that for pilgrims with religious motivations, pain could be seen as a sign of devotion. For me, struggling on gave me a sense of accomplishment. I laced those suckers back up and winced my way onwards.

Over the next several days, the Camino went from being my journey to my home, and I fell into a series of habits that doubled as survival tactics.

I’d start each day by waiting until nearly everyone had departed. Then I’d slowly prepare for the day in peace. My mind found a rare stillness. Life here was wonderfully simple: wake, walk, eat, sleep.

I stuck to a four-kilometer per hour walking pace. In the mornings I was usually in the mood to be alone, walking in front of or behind nearby pilgrims. In the afternoon I’d match up with someone whose life story I thought I’d like to hear.

Those stories were many. There was Andres, the tall young man who had started the Camino from the doorstep of his house in Freiberg, Germany. “I like to meet interesting people and be in beautiful nature,” he told me. “But I do also love walking. I need it,” he admitted.

There was the Finnish girl who dreamed of being a sailor, the young Romanian who’d fallen hopelessly in love on the Camino, the young Brit who had started in Seville, the elderly Chinese couple who lived in Manhattan. To my delight, the whole hodgepodge cast of characters kept popping up wherever I went: on the trail, in a cafe, in the bunk above me at an albergue.

Never had I felt so alone and yet so among friends. I carried this wonderfully odd feeling with me as I walked the final 20 kilometers to Santiago.

At last, the city came into sight, and then the cathedral, an epic Romanesque structure—which over the centuries had been added onto in Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque architectural styles—nearly 1,000 years old. As I approached, pilgrims were streaming in, embracing one another, crying, laughing, and praying.

It was over. I had done it. Yet as I received my compostela—the official certificate of completion—my elation was mixed with a profound sadness. My treasured simple routine—wake, walk, eat, sleep—was ending. I would return to a whirlwind life of tasks and distractions.

But then something occurred to me, something Andres had told me that very morning. “It’s not about the Camino,” he said. “It’s about following those little yellow arrows in your everyday life.”

I realized I could carry the Camino with me: its simplicity, inherent kindness and openness to strangers. Those “yellow arrows” were my own instincts, my own heart. They would tell me where to go.

I made myself a promise there and then that I would be back the following year to walk the Camino Francés from start to finish.

Only next time, I’ll bring a better pair of boots.

Veteran Profile: (Ret) Lt. General Don Laubman/DFC

Don was born in Provost, Alta., on October 16, 1921. He enlisted in the RCAF in September 1940. He was commissioned in September, 1942 and posted to the UK/412 Squadron in 1943. He flew mostly Spitfires in World War II and is the fourth highest ranking RCAF ace. On April 14, 1945 he was shot down by flak and became a POW. He later escaped by driving a Kübelwagen back to his squadron. Don was released from the RCAF in September 1945 but rejoined to eventually retire as a Lt. General.

“Come D-Day…it was incredible…as far as your eyes could see in any direction a vessel of one kind or another.”

For more profiles by Veterans Voices of Canada, click here.

Remembering the Family Oldsmobile

To our surprise, it only went in reverse. Not the car, but the large motorboat we towed behind it for six hours one summer day long ago, heading from our home in Guelph to Constance Bay, Ont. After that fun but sweaty family road trip, it was surely a let-down for Dad that the boat he wanted to test before buying could only go backwards. Boat issues aside, did that car ever get us there smoothly, all eight cylinders a-go!

The 1984 Oldsmobile Ninety Eight Regency Brougham was the second family car in my life, bought used in 1994 and retired in 2005. The years of ownership brought much delight to my family. It made for great bonding time with Dad, as we worked on the spark plugs (and the engine compartment was huge), sprayed cleaner down the four-barrel carburetor and gave it a wash. Its tan-leather seats carried us on many trips to visit family or just cruise the countryside. With so much interior room, Mom and Dad had an easy time taking all three kids, myself included, out of the car while we were sound asleep and carrying us into the house.

Sometimes, the car wasn’t so gentle. My dad accidentally pinched my friend’s finger as he rolled up the passenger side window electronically. Thinking the boy was joking about his finger being caught, Dad kept pressing the button—ouch!

As a kid, I learned the beauty of ice formation as I watched ice crystals form on the car windows. And one time—and only one time—a strange buzzing noise occurred. We were never sure what caused the sound, but it taught me, though not in a profound way, that life does indeed have its mysteries. I also learned to drive in that old car.

What led to the ultimate demise of the Ninety Eight was me removing its broken air-conditioning unit. I knew this would lower the car’s weight, which would allow it to accelerate more quickly. What I didn’t realize was that removing the air conditioner would unbalance the engine. Its removal caused the belts to squeal whenever the car was started cold, as well as at moments least desired. For example, Mom would be driving home from an emergency room night shift, praying that the car wouldn’t start squealing as she pulled into the neighbourhood. My sister took a more preventive approach: Mom or Dad were not allowed to drive her to high school in that squealing vehicle.

Eventually, with the car rusting, squealing and sporting a broken speedometer, we sold it for a couple of hundred bucks to someone in the country. We dropped it off at the person’s property. Decrepit cars spotted the area and the owner’s dogs greeted us none-too-nicely when we arrived. After saying our goodbyes to the car, we left—with our memories. I’ve often wondered if our old car is still out there in that field, and how it looks today. Is it operable? Will I see someone driving it around town fully restored? Unfortunately, brush and trees have obscured the view from the road and Google Earth is too blurry to spot the car from high above. But it is a family legacy that lives on in our hearts.

Veteran Profile: (Ret) Major Charles Gordon Owen (RCR)

Charles was born in Los Angeles, Calif, on May 3, 1929. He served as an officer of 3rd Battalion RCR (Pioneer) and after approximately 16 months of training for overseas service, he was sent to Korea. During the Chinese attack on Hill 187, he was wounded and became a Prisoner of War for several months. He was released at the cessation of hostilities in 1953. Charles retired to Victoria, B.C.

“He put the gun to my head and pulled the trigger. The firing pin hit the bullet but the bullet didn’t fire.”

For more profiles by Veterans Voices of Canada, click here.

Got a catchy caption for this photo?

Lindsey Aubin of Whitby, Ontario, shares this awesome but chilly pic, writing, “This is a photo of me doing yoga in minus 15 degree weather—it shows that if you really put your mind to it, you can overcome any obstacle, even intense cold!”

Share your funny one-liners for this photo in the comments section below or through Our Canada’s submissions site (please identify it as an entry for Caption Corner)!

Check out more Caption Corner challenges.

Don’t miss out-sign up for the Our Canada e-newsletter!