Christmas reliably falls on December 25 each year. Even if you don’t celebrate it, you probably know this fact because pretty much everything is closed on that day. But what about Easter? Sometimes it’s in March and it’s freezing. Sometimes it’s in late April and everyone can get decked out in their Sunday best without bundling up under a bulky winter coat. This year it happens to be on April 9. So, why isn’t it the same date every year—or at least the same Sunday of a particular month? Who decides these things, anyway? Well, we got to the bottom of it.

What is Easter?

Before we launch into an explanation of why Easter is on a different date every year, it’s probably a good idea to give you a little Sunday-school lesson first. Easter is arguably the holiest day in the Christian faith. It celebrates the death and resurrection of Jesus, the son of God, who was born mortal and died for humanity’s sins. While Jesus died on what we now call Good Friday, he rose from the dead a few days later on that Sunday before ascending into heaven, according to Christian dogma. In a nutshell, this is why we celebrate Easter and even more why we celebrate it on a Sunday.

But… which Sunday? All of these events happened 2,000 years ago, and we don’t have an exact date. We do, however, have a general time frame. “The Gospels depict Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection as having occurred during the Jewish feast of Passover, which happens in the springtime,” says Natalia Imperatori-Lee, PhD, professor of religious studies at Manhattan College. Jesus’ passion, by the way, refers to the events that took place in the week before his death, starting with his arrival in Jerusalem and culminating in his crucifixion; the word passion is derived from Latin and means suffering or enduring.

So, what’s the deal with the moving date?

The date of Passover changes every year, due to the lunar cycle on which the Jewish calendar is based, and Easter is linked to that holiday to some degree. But it’s more complicated than that. The Christian calendar is actually tied to the solar calendar, and the timing of the major holidays has to do with the seasons and with light. In fact, says Imperatori-Lee, this is why Christmas occurs “right around the winter solstice, after the longest night, when ‘the Light of the World’ arrives—get it?” Yep, you read that right: It’s not because Jesus’ birthday was truly on December 25.

Now, back to our spring holiday. Easter’s exact date may seem arbitrary, but it’s actually always on the Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox, and that can fall anywhere between March 22 and April 25. “Why the full moon? Maximum light! The resurrection is about maximum light—symbolically, of course,” explains Imperatori-Lee. “So, that Sunday shortly after the equinox (which has 12 hours of light and 12 of darkness) plus the fullness of the moon (lots of light) means maximum light—the perfect day for the holiest feast in the Christian year.”

For history buffs, the decision as to when to celebrate Easter—and whether or not it should coincide with Passover—was a topic hashed out between bishops at the Council of Nicea in 325 AD. A more standardized calendar, the Gregorian one, was established in the 16th century under Pope Gregory XIII, and that is actually the internationally accepted civic calendar that most of the world follows today. However, Orthodox Christians still follow the Julian calendar, the previous one created by Julius Caesar in 46 BC, meaning that Easter falls between April 4 and May 8.

Other days that shift with Easter

While Easter itself is one day, it’s part of a larger holy celebration for Christians. Once Easter is set, the other “moveable feasts” shift around it. For example, Holy Thursday (when the Last Supper was celebrated) and Good Friday (the day that Jesus died) is always the Thursday and Friday before Easter. Palm Sunday (the day that Jesus arrived in Jerusalem) is the Sunday before Easter, which is also the last Sunday of Lent. Then, of course, there’s Lent itself, kicked off by Ash Wednesday for the 40 days (not including Sundays) preceding Easter.

Does the timing of Easter have anything to do with the pagan springtime holidays?

No. However, like many other Christian celebrations, this one has likely co-opted some pagan springtime traditions over the years. Eggs may have represented fertility and birth and it “may have become part of the Easter celebration in a nod to the religious significance of Easter, i.e., Jesus’ resurrection or rebirth,” History.com notes. While bunnies may also have been associated with procreation, historians believe this tradition likely came from German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania in the 1700s and “transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called ‘Osterhase’ or ‘Oschter Haws.’ Their children made nests in which this creature could lay its coloured eggs.” Eventually, the egg-laying bunny morphed into one that simply brought treats to children on Easter.

Next, check out 10 fascinating Easter traditions around the world.

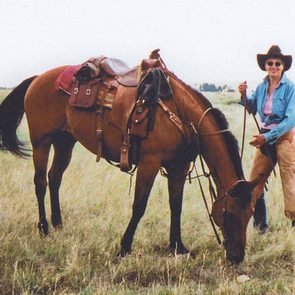

A Trip to High River, Alberta

Ever since my youth, I have had a passion for horses and photography. The top-ranking item on my bucket list was photographing wild horses. So, when the opportunity to take a trip from my hometown of Muskoka, Ontario, to High River, Alberta, came along I inquired as to where I might see some horses. My queries led me to the Wild Horses of Alberta Society (WHOAS). I visited the sanctuary, which is located near Sundre and was soon introduced to a local band of horses led by a beautiful wild stallion. That is when my quest to photograph the wild horses of Alberta began.

Like-Minded Souls

Eventually, I participated in my first exciting photography retreat at a guiding and outfitting facility tucked away in Alberta’s foothills near the picturesque Red Deer River. I arrived for my adventure on a Friday afternoon and was greeted by the friendly hosts and guided to my own cozy lodging, the “Mustang,” a charmingly rustic cabin. When I met up with the other photographers, we were complete strangers. But we had one thing in common—we were there to photograph wild horses. The head photographer of the retreat presented a slideshow with commentary; shared wild horse history, and recounted personal experiences he had with the horses. I was eager as I anticipated what the following day would bring.

Check out the wild horses of Sable Island, Nova Scotia.

A Thrilling Encounter

By morning, there was a fresh blanket of snow on the ground. It was exactly what I was hoping for as it would make a beautiful backdrop for the photos. Our group of ten climbed into two pickup trucks with our camera gear and we were off! We passed meadows and gullies covered with snow, surrounded by the beautiful foothills. We eventually stopped along a road that was off the beaten path. Beyond the alders fringed with pine trees, we heard horses snorting and squealing. What a thrill! We followed one another closely and quietly. As we crept through the underbrush we soon had a sighting. Be still, my heart! There, in a wintry wonderland, stood a dark-grey stallion with three black mares. They were stunning! I was trembling with excitement. We continued on and soon came upon a small band with a magnificent-looking bay stallion. He stood near a thicket, a light snow in the air, and kept a watchful eye on his bay mares close by. His dark-red coat was riddled with battle scars. These sightings were the first of several that weekend. I witnessed the magnificence of these amazing horses and saw the effects of their resilience and vulnerability.

Don’t miss this gallery of breathtaking horse pictures from across Canada.

Wild and Free

Some of my encounters brought different kinds of emotions. I saw many horses bearing scars from having survived a predator’s attack and was heartbroken when I heard of other tragedies that had befallen them. These emotions still arise when I think back to my visit and wonder how each of the horses is doing. I am grateful that WHOAS is an advocate for them, as I believe they are treasures to be protected.

I have continued to participate in photography retreats to Alberta whenever possible. Excitement builds as I plan each trip. I feel wonder as I watch new foals frolic in the dandelions in the lush spring birthing meadow. I sense hope as I watch yearlings role play, mimicking the adult horses. I watch in awe as powerful stallions spar for dominance. I consider the tenderness of a stallion as he gently nuzzles his mare. I witness friendships form among young exiled stallions. Most impactful of all, I see hope for these horses to continue thriving in the foothills, wild and free.

For more equine adventures near High River, Alberta, check out the wild horses of Sundre.

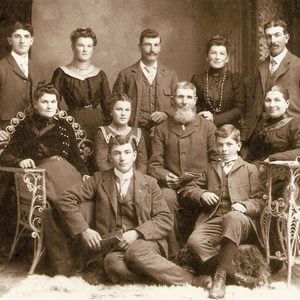

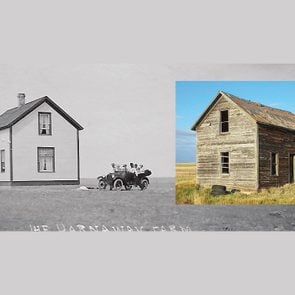

This is a story about my grandmother Veda Ramsay née Storey’s childhood when she and her family moved to North Bay, Ontario, for her mother’s health. She related it to my mother, Donna, who typed it out before it was lost forever. Here are my grandmother’s memories in her own words.

My Northern Home

On September 1, 1922, when I was 11, my parents, older brother, four younger brothers and sisters and I moved to the North Bay area (eventually we would be nine children in all). My mother was in poor health and needed to go to a drier climate for her lungs. My father had heard of government land, north of North Bay, which could be bought cheap for the clearing of partly burned forest. He talked my two uncles into going along, so they agreed to take up three sections.

My father rented a boxcar on a freight train for our furniture, cow and team of horses, as well as my two aunts’ furniture—just the things we really needed such as beds, tables, chairs and stoves. My older brother had to go in the boxcar to look after the horses and cow on the trip. On the passenger train was my father, mother, me and my brothers and sisters, two aunts and their children. My two uncles had gone on a few days ahead to be there to meet us. We got off the train in Feronia, seven miles from where our land was located. My uncles were there with the wagon. We put the younger children, trunks and bedding on the wagon, while the older people walked behind. We were 19 in all.

We put up three tents in a small clearing near an old, falling-down log shack. Each family slept on mattresses on the ground inside the tents. The men built a long, narrow shelter, which was really only a roof, and placed wooden tables down the middle beneath it, where we all ate. There was a stove without legs on the ground to cook on. This was home until the three men cut roads, cleared land and built houses. One of my cousins and I had to stay at the tents and look after the younger children, while the women went along with the men into the forest to cut logs. We were frightened at first as the wind howling through the burned out stumps sounded like wild cats.

Our house was the first one built because of my mother’s illness. It was one storey high, with a flat roof and chinked log walls. As it was only one big room, we had blankets strung on wires between the beds at one end of the room. It was built on the fork of the river where moose would come down to drink.

We had to cross one fork of the river to visit our two aunts. The bridge was made of two trees, one fallen from each side of the river. You walked down one tree and up the other one. At first we used a raft and a cable but it was too dangerous, especially in spring when the water was high.

By now, winter had set in and one aunt’s tent was banked in snow. It kept the women busy knitting socks, mittens and toques to keep warm. My mother started to gain weight and strength, and in time was completely well again. We had a good time at Christmas that first year, even though we had few gifts.

The men cut wood and each day my father went to North Bay, 15 miles away, with a load of split wood to sell. He’d bring back a load of supplies for the three families. We ate venison as there were lots of deer around and no game wardens. The road the men built was logs laid down in some places, with dirt shoveled over them. They brought the furniture that had been stored in Feronia over these log roads as each family’s house was built.

It was tiring work to clear the land, burn the logs and then pick up the partly burned pieces to re-pile and burn again. My mother made us aprons out of jute bags to try and keep our clothes clean.

We had no school for two years. My mother finally wrote to the minister of education telling him about us not having a school for the 13 children. They came to see us and my father and uncle built our first schoolhouse. We older children handed the lumber up to the men for the roof.

We got a teacher from Cobourg, Ontario. My brother and I went to Feronia to meet her train. We took the lumber wagon with straw in the back to put her trunks on; where the roads were log underneath we had to stand up it was so bumpy. We thought she was the prettiest person we had ever seen and her clothes were so nice.

Our family had built our second house by the time the teacher came—we always boarded the teacher for the time we lived there. Our second house was made of pulled logs on the outside and framed inside. It had four bedrooms and we thought it was a mansion when we first moved in.

My father acted as a land guide for the people coming in to take up land the same way we did. A man would arrive in Feronia by train and stay at our place overnight. My father would take him to see his land the next morning and he would catch the train back again that day.

About two years later, my father built a general store, which supplied the families in the mill camps. My mother baked all our bread and some for other people as well. When we started getting bread in the store, it came in clean, new jute bags. Things like raisins and prunes came in wooden boxes. I had to dig them out and put them in paper bags, five pounds for 25 cents. The school kids came in for a cent worth of candy at noon hour.

My brother John and I often walked to Feronia with a haversack on our back to carry in groceries and get the mail. My older brother Floyd had to work with my father and uncles. The older boy in the other family went away to school and became a teacher.

We started having Sunday school in the schoolhouse and then a student minister began coming a couple of times a month. The school was near our house so we always had the minister for dinner and most times had to go to meet him and take him back as we had a car by this time.

In winter, we never saw North Bay or any town from Christmastime until spring and then only in the latter part of the eight years we spent there. We had to put the car away in winter on account of the deep snow. My older brother and I thought nothing of walking or snowshoeing two or three miles at night to visit friends. Sometimes, I’d step on the back of his snowshoes, when the wolves sounded close with their howling.

I remember the first time I went to North Bay, I rode on a load of wood with my dad. It was -40°F when we left at 4 a.m. At first I walked behind to keep warm. In town, he let me off on the main street and told me to stay on the block between the restaurant and Woolworth’s so I wouldn’t get lost. He had to go to market and sell the wood. He was to meet me at the restaurant for dinner when he finished. I was so pleased with all the stuff in Woolworth’s that I stayed there most of the time as it was too cold to stay outside. We ate at the restaurant; it was the first time I was ever in one. We got home after dark that cold night. I never asked to go again.

My father continued to work hard. He cleared 35 acres of land, raised cattle, built roads and a bridge, bought another woodlot and logged. We boarded surveyors and river drivers, who drove logs down the river to lumber mills. Mom and I fried bacon and eggs in dripping pans on top of the stove at 4 a.m. for their breakfast. I also remember entire families staying at our place for a few days while their homes were being finished.

There were times we had terrible forest fires. I remember firefighters and even the army camping in tents around our house. They had water haversacks to carry the water. You could see to write a letter by the light from the fires at night. One of my aunts heard the fire was coming, so she took her fur coat and just walked out of her house. The fire burned her home. Her hens were still alive in the clearing afterwards, but she had to kill them as their feet were so badly burned. Thankfully, as more people bought, settled and cleared more land, we had fewer forest fires.

Legacy of Love

I have such amazing memories of my grandmother, a kind, loving woman who treated you like royalty when you visited her home. Her experiences in North Bay, and as the eldest daughter in a family of nine children, made her someone who loved deeply, putting her family’s needs ahead of her own. Both she and my grandfather are missed to this day, but their legacy of love and sacrifice lives on.

Next, find out what Prairie life was like during the Great Depression.

Gas has always been a sizable household expense, particularly for commuters, but it’s making an even bigger dent in our wallets now. And, with inflation significantly impacting the cost of groceries and other consumer goods, Canadians are more eager than ever to find cheap (or at least less expensive) fuel at the pumps.

Here are four ways to save money by finding the cheapest gas station near you.

Use an app to find the cheapest gas station near you

If you have a smartphone, you’ve got a money-saving tool right in your pocket. Try downloading an app like Waze, which not only helps drivers navigate traffic using real-time information but also shows you how much fuel costs at nearby gas stations. Similarly, CAA members can use their app to view a list of local gas prices and decide where to fill up, or simply check out local gas price trends by using their website. There’s also Gas Guru, which lists nearby gas prices and lets you flag your favourite local gas stations to keep an eye on them, and GasBuddy, which displays pricing and allows users to collect “GasBack” points that can be redeemed for free fuel. Insurance provider Geico also has an app that includes a gas price comparison tool that’s quick and easy to use (and no, you don’t have to be a customer to access it).

Ask your neighbours

That retired guy down the street may have the scoop on the cheapest gas station near you. And if you don’t have a friendly neighbour who’s in-the-know, try joining local Facebook groups. An online community is often the best place to get tips from local deal-hunters who are more than happy to share their successes. Look for a group that’s active, engaged and aims to be a helpful community hub. All you need to do is search for a thread about current gas prices or start one yourself, and watch the tips roll in! If you’re not on Facebook, consider joining alternatives like NextDoor.

Take advantage of retail memberships

The next time your gas light comes on, consider filling up at a local Costco. Members get a significant discount on fuel when they fill up at a Costco gas station. Plus, if you pay with a Costco Mastercard, you’ll earn cash back. The downside of this option is that Costco gas stations tend to have shorter hours—and longer lineups—than their competitors. That said, if you tend to buy gas early in the morning or during normal retail hours (as opposed to late at night), this shouldn’t be a problem.

In addition to retail memberships, it’s worth looking at gas stations that offer rewards points, cash back or other benefits. Brands like Esso, Petro-Canada and Canadian Tire all have customer rewards programs, and there’s no harm in signing up for all of them (particularly if getting a points card is free). You can also speak to your financial institution about credit cards that come with a permanent discount on gas (for example, this RBC credit card that offers 3 cents off every litre of gas purchased at Petro-Canada, or this Scotiabank credit card that offers 2% cash back on every dollar spent at eligible gas stations). In addition to saving money through apps and word of mouth, you can count on some perks when you shop this way.

Time it right

According to research by GasBuddy, it’s not just where you buy your gas that matters—it’s when. There are more expensive days of the week to buy fuel—Monday and Friday, for example—and days when gas is cheaper. If you want to get the most bang for your buck, try to fill up on Tuesday or Wednesday mornings. Sunday and Wednesday evenings aren’t bad, either, but avoid Fridays if you can—fuel prices tend to spike as we drive into the weekend. Safe travels—and happy savings!

Now that you know how to find the cheapest gas station near you, check out the best apps to save money on groceries.

If you live where winter is a five-month-long ice and snow storm, you shouldn’t wait until summer to give your cabin a well-deserved deep cleaning. While cleaning out the interior, you may notice unsightly road salt stains. Here’s how to make quick work of this cleaning task.

How to remove salt from car carpet and floor mats using vinegar

Step 1: Gather your supplies

- 1 spray bottle

- 1 bottle of household distilled white vinegar

- Hot water

- Scrub brush with hard bristles

- Dry cleaning cloth

- Wet/dry vac

Step 2: Make the solution

- In the spray bottle, make a cleaning solution consisting of 50 per cent vinegar and 50 per cent hot water. (Don’t miss these other brilliant uses for vinegar all around the house.)

- Spray the solution onto the affected areas (car carpet and floor mats will likely have the most salt stains).

- Let the solution sit for a few seconds, then scrub vigorously with the scrub brush.

- Soak up the remaining mixture with a dry cleaning cloth.

- Use a wet/dry vac to suck up any remaining solution and salt residue.

- Hang floor mats to dry. If parked inside, you can keep the windows rolled down to air out the vinegar smell.

How to remove salt stains from your car using foaming carpet cleaner

Step 1: Gather your supplies

- Foaming carpet cleaner

- Scrub brush

- Wet/dry vacuum

Step 2: Apply foaming carpet cleaner

- Spray the foaming carpet cleaner generously on the salt stains.

- Use the scrub brush to gently work the salt up to the surface.

- Allow the cleaner to dry.

- Vacuum up the dried residue.

Now that you know how to remove salt from car carpet, find out how often you should wash your car in the winter.

The idea that red means stop and green means go affects more than just traffic lights. We’ve been taught from a young age that red means danger, while green means safety. But why were those particular colours chosen for traffic lights in the first place? For something we have to look at every day, why couldn’t they have been prettier colours, like magenta and turquoise? You’re about to find out.

When were the first traffic lights created?

The first traffic lights in North America were installed because of an increase in travellers on the road in the 1920s. Worried about accidents, towns and cities installed traffic towers to help the flow of cars. Officers manned the towers, using whistles and red, green and yellow lights to indicate to drivers when they should stop and go.

Then, in 1920, William Potts created the first tri-colour, four-directional traffic signal. It helped drivers stay safe at intersections. The very first four-directional traffic light was installed at Woodward Avenue and Fort Street in Detroit, Michigan.

What’s the history behind the colours?

It’s important to know that before there were traffic lights for cars, there were traffic signals for trains. At first, railroad companies used red to mean stop, white to mean go and green to mean caution.

As you can probably imagine, train conductors ran into a few problems with the colour white meaning go—bright white could easily be mistaken for stars at night, with train conductors thinking they were all clear when they really weren’t. Railway companies eventually moved to the colour green for go. And because it’s easily distinguishable from the other colours, yellow became the standard for indicating when trains should proceed with caution. It’s been that way ever since.

When traffic lights were put up, it became standard for them as well.

Why was red chosen for stop?

Red is the colour with the longest wavelength; that means that as it travels through air molecules, it gets diffused less than other colours, so it can be seen from a greater distance. For a real-world example, think about how the light turns red as the sun sets. Even though the human eye is most sensitive to a yellow-green highlighter colour (hence the shade of high-visibility safety vests), it can see red from further away.

Yellow has a shorter wavelength than red but a longer wavelength than green. This means that red is visible the furthest away, yellow in the middle and green the least distance away—a helpful advanced warning for needing to slow or stop. But this could be a coincidence. Red meaning stop originated with train warning lights, and it’s not clear whether that was chosen based on wavelength, contrast against green nature or natural association of red with things like blood. It could be a combination of all three!

Believe it or not, yellow was once used to mean stop, at least as far as signage goes. Back in the 1900s, some stop signs were yellow because it was too hard to see a red sign in a poorly lit area. Eventually, highly reflective materials were developed, and red stop signs were born. Since yellow can be seen well at all times of the day, school zones, some traffic signs and school buses continue to be painted the colour.

Next time you’re impatiently waiting at a traffic light, don’t get mad; be thankful that traffic lights have come a long way.

Next, find out why cars have gas tanks on different sides.

When was the last time you cleaned your wooden spoons? No, like really cleaned them? A viral TikTok video by a 20-year-old student teacher has sparked a cleaning trend for the cooking utensil.

In the video, which has climbed to more than 20 million views, user Bonnie McNamara soaks a wooden spoon in boiling water. The spoon then begins to shed layers of what appears to be caked-on food. Watch and observe in the video below.

@miss.clean.with.meI was not prepared for this🤢 Tiktok teaches me so much! #clean #cleaning #satisfying #asmr #cleantok #foryou #fyp♬ Bubble pop electric – 𝔞𝔲𝔡𝔦𝔬𝔰 ꨄ

Users had mixed reactions. Some were repulsed by the video, while others appreciated the deep-cleaning discovery. One top commenter, @winniethelou, wrote, “sometimes I like to remain in ignorance. This is one of those times.”

McNamara, who runs the popular @miss.clean.with.me account, has more than 200,000 followers on the popular social media app. Her videos, which focus on cleaning hacks, have more than 5.5 million likes.

A Yahoo article says the best way to clean a wooden spoon over the long term is to “wash it with hot water and soap quickly after each use,” then “patting it dry with a clean cloth and then letting it air dry before putting it away.” Another option is to use a diluted bleach solution to disinfect wooden spoons.

“Restaurants employ this step, plus a high-temp dishwasher cycle, to eliminate bacteria on the surface of these versatile utensils,” a My Recipes article suggests. “At home, however, this isn’t really necessary unless you just prefer to go the extra mile.”

Next, check out the viral trick that will make your pots and pans look brand new.

If the late 17th century was the worst time in history to be a witch, the early 21st might just be the best. WitchTok, a TikTok hashtag celebrating hexes, covens and goth glam, has more than 34.5 billion views. Movies from the 1990s, like Hocus Pocus and The Craft, are trickling down to current-day audiences, while new film adaptations, such as the musical Wicked (starring Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo) are bubbling in the Hollywood cauldron. It’s an aesthetic movement, yes, but also a political one. There’s something powerful, especially now, about women, queer people and racialized communities using magic to revolt against their patriarchal oppressors.

One of the latest incarnations of the witch trend is VenCo, a new fantasy novel from The Marrow Thieves author, Cherie Dimaline. Our protagonist this time is Lucky St. James, a young Métis woman living in a roach-infested apartment in Toronto with her grandmother, Stella, who is in the early stages of dementia. Lucky is sick of her rudderless life, her dull office temp work and the tattooed object of her affection, who doesn’t share her feelings. She’s sustained by memories of her mother, Arnya, who taught her wisps of Métis magic—like how to plant booby traps for villains in her dreams—before dying when Lucky was 10.

Where Narnia had its wardrobe and Wonderland its rabbit hole, the otherworldly passage in this book is a tunnel behind a cabinet, where Lucky finds a souvenir spoon inscribed with an etching of a witch and the word “Salem.”

We learn there are seven such spoons in the world, each magically unearthed by a potential witch, and soon Lucky is hired by VenCo, a recruiting firm headquartered in California that’s a cover for something much more mystical. (While conceiving the novel, Dimaline wanted the talisman to be something mundane, and she serendipitously discovered that the first mass-marketed souvenir spoon was made in Salem, Massachusetts.)

Dimaline, who is a member of the Georgian Bay Métis Community in Ontario, has a reputation for shaking up old-fashioned horror stories. She’s best known for The Marrow Thieves, a YA series that offers an ingenious twist on the post-apocalyptic genre: it takes place in a world where only North American Indigenous people can still dream, and factories are built to harvest their bone marrow and steal their power. She later released Empire of Wild, which follows a woman who believes her husband has been transformed into a rougarou, a werewolf-type beast from Métis folklore.

In VenCo, she diversifies the traditional witch narrative by conjuring an inclusive coven of Black, Indigenous, queer and trans women who are empowered by the things that marginalize them in mainstream society. The sparkling cast of characters includes Lettie, a Creole single mom; Freya, a trans woman; and Meena, a descendant of healers from the West Indies and an American colonial witch.

The best thing about the novel, though, is that it’s a rollicking load of fun: a female buddy comedy complete with road trips and scissor-sharp banter, like if Bridesmaids included prophetic dreams and water divination. The women feel lived-in and true, their dynamics alternately warm and spiky. Lucky is an unforgettable central character, a witch’s brew of guarded grumpiness and aching vulnerability. By the end of Dimaline’s book, you find yourself wanting to live with these characters forever.

Next, check out 10 Indigenous authors you should be reading.

When it comes to keeping infectious diseases at bay, washing your hands really does go a long way. However, you probably didn’t know that drying your hands can be just as important as washing them.

“After washing your hands, it is so crucial that you dry your hands thoroughly,” Nesochi Okeke-Igbokwe, MD, a physician and health expert says.

Wet hands easily transfer or pick up germs. You could drip bacteria-infected water—and anything wet hands touch could become contaminated, according to David Cutler, MD, a family medicine physician at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California. Bacteria is more likely to transfer from wet skin than from dry skin.

Some research shows there is a superior drying method

After you’ve taken the 20 to 30 seconds to wash your hands, it’s important to ensure they’re fully dry. “One goal is to ensure that you do not re-contaminate the hands with bacteria in the process of washing or drying the hands,” Okeke-Igbokwe says. So if you have the option to dry your hands with paper towels, cloth towels, or an air-dryer, it’s more important to choose one rather than leave your hands to air dry. However, some research shows there is a superior way to dry your hands—with paper towels.

According to research from Mayo Clinic, electric air hand driers actually have the potential to spread bacteria by blowing the pathogens right back onto your hands after washing, Okeke-Igbokwe explains. “Using hand dryers in public restrooms is the worst way to dry your washed hands,” Dr. Cutler says. “Hand dryers pose risks especially to young people whose face may be at the nozzle level and breathe in the bacteria or get injured by the heat.” Another study from Westminster University found the most powerful hand driers can spread a virus up to one and a half metres (almost five feet) across the room. Although some experts still debate this topic, drying your hands with a clean, single-use hand towel may be the safer choice to reduce the risk of spreading germs, according to Okeke-Igbokwe.

Bottom line: Always dry your hands

The least-safe option is not drying your hands at all. Ranekka Dean, the Director of Infection Control at NYU Winthrop Hospital in Long Island notes that studies on each drying method have strengths and weaknesses, but as long as your hands are completely dry you’re making a healthy choice. “The decision to use a specific drying method may be determined by several factors, including practicality, personal preference, cost, space, and availability.”

Next, check out the bathroom mistakes you didn’t know you were making.