Thawing food properly is a big deal, but it can feel like a pain. Luckily, learning how to defrost chicken safely isn’t as difficult as you might think. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has identified three safe ways to thaw meat (including one last-minute technique if you forget to defrost in advance). Plus, it turns out chicken is one of the meats that’s safe to cook from frozen.

How long does it take chicken to defrost?

The USDA says that food is safe indefinitely in the freezer, but bacteria can start to grow during the thawing process. That happens when the food’s temperature rises above 40°F (4°C). Using unsafe thawing methods can lead to the centre remaining frozen while the outer layer of meat is in the “danger zone.” This temperature range (between 40°F and 140°F, or 4°C and 60°C) allows bacteria to grow and rapidly multiply, and food kept at these temperatures for extended periods can cause foodborne illness.

Large roasts or turkeys can take a long time to thaw. To defrost a turkey, for example, takes 24 hours for every five pounds of weight! Luckily, chicken is relatively small, especially if you’re thawing small cuts like boneless skinless chicken breasts. Each thawing technique has its own timeline, so read on to learn the best way to thaw chicken using the USDA’s three recommended methods. (Here are 13 things you need to know about food poisoning.)

How to Defrost Chicken

Method 1: How to defrost chicken in the refrigerator

This is the slowest way to thaw chicken, but it’s also the safest. In fact, it’s so safe that you can wait a few days before cooking the chicken, and you can even re-freeze it if you need. That’s because the refrigerator keeps the entire chicken at safe temperatures during the entire thawing process.

Remove the chicken from the freezer and place it on a plate to catch any drippings that may release while the chicken thaws. As a general rule of thumb, it should take anywhere between 12 to 24 hours to thaw boneless skinless chicken breasts. It may take an extra day to thaw a whole chicken or chicken cuts that are frozen together in a large chunk.

Method 2: How to defrost chicken in cold water

If you forgot to pull your chicken out of the freezer ahead of time, this method is your best bet because it’s a little faster than the refrigerator. You will need to keep a close eye on the chicken during the thawing process, though, to ensure it stays at safe temperatures. It’s important to cook the chicken as soon as it’s thawed, too, and it’s not safe to refreeze it unless the chicken has been cooked.

Keep chicken in the original packaging. If the packaging is damaged in any way, remove the chicken and place it in a leak-proof package, like a freezer bag. Fully submerge the chicken in cold tap water. You can use a large bowl if the chicken will fit, or fill the sink with enough water to cover the chicken. From there, you’ll need to change the water every 30 minutes to ensure the water doesn’t warm up and reach the danger zone. Small chicken cuts should thaw in about an hour, although a whole chicken may take up to three hours.

Method 3: How to thaw chicken in the microwave

This is our least favourite method for thawing chicken, but it’s also the quickest. Thawing chicken in the microwave leads to uneven thawing, so the outside can be in the danger zone while the inside is still frozen. That means you’ll want to cook the chicken right away to prevent any bacteria growth.

Start by unwrapping the chicken or removing it from its packaging. Place the chicken on a microwave-safe plate and consult your microwave’s manual to determine the proper power level and timing. If you don’t have the manual, set the microwave to defrost (or 20 percent, if your microwave doesn’t have a defrost setting). Cook the chicken in two minute intervals, turning it and checking to see if it’s done. Repeat the process until the chicken is no longer frozen. It may take as long as ten minutes, depending on your microwave.

How to Cook Frozen Chicken

When all else fails, you may be able to cook your chicken straight from the freezer. According to the USDA, frozen chicken takes one and a half times as long to cook, so you’ll need to increase your cooking time by 50 percent when cooking it on the stovetop or in the oven. You can also cook frozen chicken in an Instant Pot.

If your recipe calls for cooking chicken for an hour, you’d want to cook it for 1-1/2 hours. Before you get started, remove any wrapping and paper inside the package. When cooking a whole frozen chicken, remove the giblet pack from the cavity as soon as you can loosen it.

Keep in mind that not all cooking methods work well with frozen chicken. It’s safe to cook most frozen chicken in the slow cooker, although we suggest cutting it into small pieces before cooking it. It wouldn’t be safe to cook a frozen whole chicken in the slow cooker, though, because it will take too long to thaw, keeping it at the danger zone temperature for an extended period. (Find out the foods you should never put in a slow cooker.)

Tips for Thawing Chicken

Our best advice for thawing chicken is to be patient. It can take a day or longer for chicken to defrost in the refrigerator. We’ve discussed quicker methods if you’re running short on time, but it’s really important to avoid thawing foods on the kitchen counter, outdoors or in hot water. These methods hold part or all of the chicken at improper temperatures, increasing your risk of foodborne illness. Take your time and plan ahead, or use our method for cooking chicken straight from the freezer.

Now that you know how to defrost chicken, find out the expiration dates you should never ignore.

At the local school here in the small town of Eaglesham in northern Alberta, my colleague and fellow teacher Mike McKay gives his students a unique lesson every Remembrance Day.

Before coming here to teach at Eaglesham School, Mike served as a reservist in army communications. As the students here got to know “Mr. McKay,” they had lots of questions for him about his time in the military. The students had many misconceptions about what it was like—mainly due to the video games they play—so one day in 2007, Mike said, “Let’s go dig trenches and stay in them all night, so you can see what it is like to be a soldier.”

It was a pretty miserable night, but it was the beginning of something real for these kids. The following year, they wanted to do it again—and again. Now, years later, students are still looking forward to experiencing this special event.

Students from Grades 7 to 12 are invited to spend a night “in the trenches.” For the last couple of years, they have been digging their trenches on the back field at the agricultural fairgrounds in town, which is within walking distance from the school.

They are provided with a list of items to bring that must all fit in a pack on their backs, along with a pick and shovel to dig their trenches. Mike has students perform guard duty and provides a distraction during the night to mimic wartime, to see how they cope.

Community groups provide a hot supper of stew, and a breakfast of oatmeal before students fill in their trenches and head to the hall for the Remembrance Day ceremony.

In the years he has been doing this, Mike has experienced all kinds of weather, including rain, snow and temperatures ranging from as low as -30°C to weather so warm that you are bathed in sweat when finished digging your trench. The students always say that they’ll never again view Remembrance Day as just a day off from school.

Perhaps some of the greatest learning comes the day after the trench digging, when students have to run the community Remembrance Day ceremony. Each student has to do a presentation on a relative or friend who served either during war or peace time. The students’ presentations have covered relatives who served on opposite sides of a war; who served in wars that the students had never even heard of; and who were lost in war, but whose remains were never found.

As a result, these youngsters all become keenly interested in their family histories as well as gain a better understanding and respect for the significance of Remembrance Day.

Don’t miss these Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.

During the early 1940s, four veterans of the First World War lived within a two block radius of our home, in Stratford, Ontario. One had served with General Edmund Allenby in the Middle East campaigns. Another, a shell-shock victim, would stand in his mother’s yard, stiff as a ramrod, for hours on end, occasionally throwing his arms around but never saying a word. Our father’s best friend lived down the street from us, and was still alive after surviving a gas attack and the horror of being buried alive. Then there was our dad, George William Trowsdale, who carried shrapnel in his right leg to the grave.

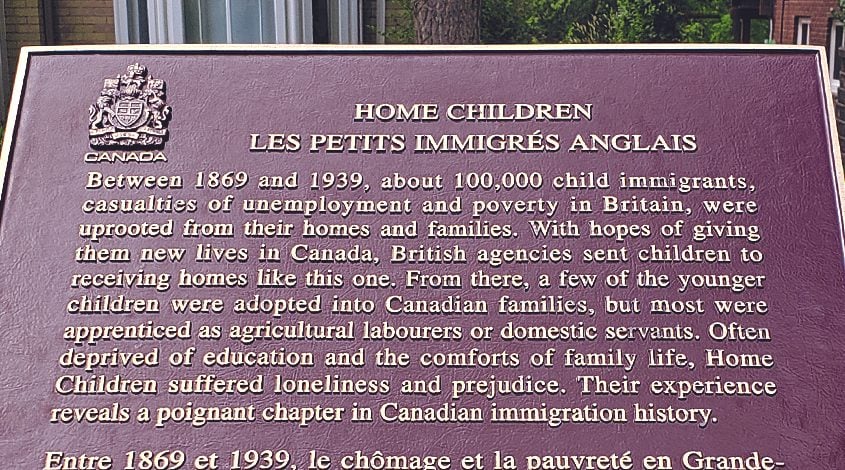

Dad and his younger sister were born in an English workhouse. Decades later, she told my sister Brenda and me how they had searched railway tracks, looking for partially burned cinders for their winter heat. When their father died and their mother disappeared, they ended up in two separate Catholic orphanages. The one my father attended was called The Children’s Homes of the Sheffield Union. In 1913, he sailed for Canada as a “home child” immigrant, and worked as a farm labourer near Tillsonburg, Ontario. Enlisting in the Canadian army on March 9, 1916, he didn’t find out his true date of birth—August 20, 1900—until sending in an application for his birth certificate in 1927. At the time of enlistment, he was unaware that he had joined up as a 15-year old.

He served initially in the 168th Battalion, and then transferred to the Machine Gun Squadron of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade on March 7, 1917. I first heard about his transfer during a conversation he had while purchasing a painting of a First World War cavalry machine gun squadron, in Vancouver. Wounded in Trouville, France, in 1918, he was discharged from an Australian field hospital several months later in Rouen, France, and left without his collection of war souvenirs. The only specific item I remember he brought back was a German Uhlan cavalry helmet.

He decided to move back to England in 1919, but when he found out that his aunt, whom he had sent his pay for safekeeping, had disappeared, he returned to Ontario and settled in Stratford after a brief stay in Detroit.

He only ever told us three war stories. The first was about his decision to give up his sergeant’s stripes because of what he had to enforce. The second was about his punishment in the “glass house,” a military prison for soldiers who have broken certain rules. The only thing I recall him saying about that was, “once was enough.” The last story he ever told us was about his decision not to join three friends who had been members of the North-West Mounted Police (later the RCMP) before enlistment and wanted him to join them after demobilization. Brenda and I always found it amusing when he struggled to admit that our mother, who had grown up on a farm and could do almost anything associated with horses, was actually just as good, if not better, at handling them than he was.

Upon his return from the war, he began correspondence courses for a high school certification and also worked as a machinist’s helper for the Canadian National Railway. His first major purchase as soon as he saved up enough money was a piano, which still remains in our family home in Stratford. He began taking piano and voice lessons, decided to enter a singing class in Ontario’s first competitive music festival in 1927 and ended up winning the first-place prize. I can still remember being played to sleep at night with one of my favourite 1920s songs, “Doll Face.”

After completing the courses necessary for promotion to full machinist, he went on to survive the Depression. Rather than taking out a mortgage on a house that was built in 1858, he decided to rebuild it himself.

With a major interest in Freemasonry, he achieved his ambition of getting accepted into the Shrine, but passed away just before his oft-stated goal of living to three score and ten. An important part of his life from the early ’30s until his death in 1969 was the Masonic Lodge in Stratford.

It’s estimated that there are now over three million descendants of the more than 80,000 British home children who came to Canada between 1875 and 1933. Not only was this our personal legacy, it was the legacy of many other Canadians as well.

Check out more Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.

A Road Trip to Remember

My first attempt at capturing the perfect photo of Peyto Lake, a glacier-fed lake located in Alberta’s Banff National Park, was a couple of years ago. My girlfriend, Andrea, and I took a road trip across North America in which we travelled through 28 states and three provinces, covering a total of 20,919 kilometres!

Luckily, we didn’t have any car trouble throughout our trip, other than figuring out who was going to drive to each destination—it was mainly me. In the States, we purchased a pass that gave us access to all the national parks, and camped in as many as we could. The whole adventure took us two and half months to complete and was one of my all-time favourite trips.

While on the West Coast, we crossed back into Canada to visit beautiful British Columbia and Alberta. We arrived in Banff National Park at the end of April, which back home in Ontario would have been spring, but unfortunately in Banff still meant winter. Andrea had visited Banff before and bragged about how blue the water was in all the lakes. I had envisioned that the ice would be melted, revealing the crystal-clear blue water beneath.

That morning, we woke up early, grabbed a quick bite to eat, a coffee to go, zipped up our winter jackets and headed out the door into the brisk morning air. I was so excited to start our day. I had planned to drive along the Icefields Parkway, which starts in Lake Louise and goes all the way to Jasper with many viewpoints along the way. One of the stops included Peyto Lake, where I was hoping to capture the perfect photo with the snow glistening on the evergreens and a lake as blue as blue can be.

Unfortunately, after a short hike to the viewpoint, I looked out and all I saw was frozen lake completely covered in snow. It was still beautiful but I knew deep down I really wanted to capture the lake when the water was as blue as the sky.

Discover the best road trips in Canada.

Return to Peyto Lake

Fast forward two years, and we had the opportunity to return. This time around, the timing was perfect and I knew I would have a good chance at capturing the photo I had imagined in my mind.

This trip would be a little different as we were attending a friend’s wedding, where I would also be their videographer for the day. We were supposed to arrive the day before the wedding, however the night before our flight, Andrea thought I had set an alarm and I thought she had set an alarm. It turned out that neither of us had and we arrived 20 minutes after the gate had closed! We’d missed our flight and were told we would have to book another one. I couldn’t believe it! I’d flown so many times before, and I had never missed a flight in my life.

Luckily, we were able to book another flight the next morning. Yes, the day of the wedding. As a wedding videographer this is a nightmare. After spending the night with one eye open, we arrived on time the next morning, boarded the plane and made it to the wedding just in time!

We had two days after the wedding for exploring and I knew exactly where I wanted to go, back to Peyto Lake! When we arrived, the parking lot was blocked off but that didn’t stop us from hiking through a few inches of snow to reach the viewpoint. When we got there, it was just as I had imagined—not another soul in sight, it was perfect. I finally captured the shot I wanted. I have travelled to many other countries but I believe this is my favourite landscape to date!

Next we visited Moraine Lake, which was already frozen. We were able to walk right out onto the lake, capturing some photographs of the ice and mountains. The final lake we visited that day was Lake Louise. There was an option of canoeing on the lake but since we were pressed for time we decided to do a walk around the lake instead.

Later that night, we met up with friends from the wedding for dinner in Canmore. Here we all planned out our final day of the trip. The morning came quickly and the nine of us set out. We drove through Banff National Park and stopped at Castle Mountain, then at Morant’s Curve, a scenic viewpoint near Lake Louise where trains pass through the Canadian Rockies.

We continued our journey to Yoho National Park. After spending the afternoon on the trails, we headed back to Canmore where Andrea would stay for an extra day but I had to catch a flight home as I had another wedding to film.

I will always remember this trip and look forward to another visit to Peyto Lake!

Next, check out seven restaurants in the Canadian Rockies that are as impressive as the scenery.

Remembering My Grandfather, George Foote Foss

As a young boy, growing up in Fort Chambly, Quebec, from time to time, I would hear stories of my grandfather George Foote Foss and his invention. I would overhear these stories as my father shared the details with friends and neighbours who were visiting our home. However, the stories that I most often heard came directly from my grandfather, as we visited him frequently. I recall fondly sitting on a footstool near his feet as he sat in his large, comfortable chair, recounting the steps he took in tinkering, planning and, ultimately, building a gasoline engine automobile, which was to be the first in Canada—later dubbed “the Fossmobile.”

In the early 1960s, when I was about seven years old, I recall that everyone around me was talking with a flurry of renewed interest about his accomplishment. It was then that he was presented with two honorary memberships: one from the Vintage Automobile Club of Montreal (VACM) and the second from the prestigious Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA). Only two Canadians have ever received this latter honour. The other Canadian to receive it was Colonel Robert Samuel McLaughlin, who started the McLaughlin Motor Car Company in 1907, one of the first major automobile manufacturers in Canada.

With these two initiatives, there came a swarm of media attention, and I can recall being shown newspaper clippings, many of which I still have in my possession today. Not only were there photos and articles written about his honorary memberships, but many of the local papers also reprinted his earlier writing of “The True Story of a Small Town Boy,” originally published in 1954 by The Sherbrooke Daily Record.

Having a relative with historical significance meant that most of his descendants have ended up using his Fossmobile story, and the various publications about its invention, as a topic for school projects. I recall doing precisely that in school, both of my two children did so as well, and just a year ago, my six-year-old granddaughter did a show-and-tell at school about her great-great-grandfather’s invention.

Completing the Fossmobile

George Foote Foss (September 30, 1876-November 23, 1968) was a mechanic, blacksmith, bicycle repairman and inventor from Sherbrooke, Quebec. It was in early 1896, during a trip to Boston to buy a turret lathe for his expanding machine shop, that my grandfather saw his first automobiles. These cars, electrically driven broughams, were rented out for $4 an hour. He paid the fee to have a ride, but unfortunately, after a ride of only half an hour, the batteries died. Returning to Sherbrooke, he decided to build an automobile that would address this problem.

And so during the winter of 1896, he developed a four-horsepower, single-cylinder gasoline-powered automobile. In the spring of 1897, he completed the Fossmobile and it became the first successful gasoline-powered automobile to be built in Canada.

Saying “No Thanks” to Henry Ford

My grandfather drove his car in and around Sherbrooke for four years. He later moved to Montreal, where the car sat idle for a year before he sold it for $75 in 1902. He had previously turned down an offer to partner with Henry Ford who went on to form the Ford Motor Company. He turned down the offer, as he believed Ford’s Quadricycle vehicle to be inferior to the Fossmobile. He also turned down financial backing to mass-produce the Fossmobile, citing his inexperience to do so, as he was only 21 years old at the time.

I am often asked if I know if my grandfather had any regrets about not partnering with Ford or not mass-producing his invention. From everything I recall hearing him say, he had no regrets. He enjoyed a simple life, and I heard him say on more than one occasion, “You don’t live a long life with the stresses of running a big business.” He passed away at age 92, so perhaps his theory was right, at least for him.

Recently, I reopened the Foss family archives to better understand and accurately document my grandfather’s remarkable accomplishment. My objective has been to find ways to share this historic Canadian event with automotive enthusiasts, historians and future generations of Canadians. To this end, I have established Fossmobile Enterprises, as a means to build networks, foster collaboration and share important historical memorabilia.

A Tribute Fossmobile

As George Foss’s grandson, I have talked with some visionaries and I am seeking the help of other potential experts in vintage automobile restoration for a very special project. The goal is to use reverse engineering (the reproduction of an inventor or manufacturer’s product) to create a Tribute Automobile, emulating as closely as possible the specifications of George Foss’s invention of the first gasoline-powered automobile built in Canada: the Fossmobile. There are no original drawings, so the Tribute Automobile will have to be based solely on detailed scrutiny of original Fossmobile photos.

I began the process of acquiring vintage parts from the era, with the hope of building this automobile, replicating parts only when it was absolutely necessary. I have provided hands-on oversight for this process, collaborating with historians and experts. We have found and fully restored an engine, a chassis, wheels and a period-correct wood body. Custom woodworking has been completed for the seat and engine cowl. Additionally, mechanical fabrication was needed for the steering tiller and the chain-driven sprockets. With every step the journey has been well documented, ensuring attention to the smallest of details.

The plan is to honour my grandfather’s legacy and bring to greater light this significant chapter of Canadian automotive history. All original photos, journals and related documents have been donated to Library and Archives Canada. Upon its completion, this tribute Fossmobile will be a tangible embodiment of the first gasoline automobile built in Canada. It will eventually be donated to the Canadian Automotive Museum to enhance historic education for current and future Canadians.

Discover 20 mind-blowing artifacts you’ll find in Canadian museums.

Dark green vegetables are often considered to be the cream of the health-food crop because they’re particularly rich in essential minerals like iron, magnesium and calcium, as well as vitamins C, K and many of the Bs. Now an array of products, from brands like Athletic Greens and Vital Proteins, promise all that goodness in one simple scoop of powder—just stir it into a glass of water. The powders are made of dehydrated veggies such as spinach and beetroot, plus spirulina, a type of algae full of nutrients.

Are green powders a waste of money?

But is drinking your greens as healthy as consuming them whole? The short answer is no. “I consider powdered greens to be a nutritional supplement,” says Maya Feller, a New York-based registered dietitian and author of Eating From Our Roots: 80+ Healthy Home-Cooked Favorites From Cultures Around the World. “Many of these products have added vitamins and minerals or other nutrients that don’t naturally occur in green vegetables, so they’re similar to a multivitamin.”

The crucial element many are missing is fibre. Fibre is good for your gut, helping to keep food moving through the digestive system. It’s found in whole vegetables, but most juices and powdered greens have little to none.

Still, getting your daily servings of vegetables isn’t always convenient—and that’s where green powders may come in handy. “They can help bridge the gap when you’re not able to meet your nutritional needs by food or beverages alone,” says Feller.

So are green powders are a waste of money? As a straight-up substitute for fibre-rich vegetables, they don’t deliver the best return on your investment. On the other hand, if you’re merely looking to supplement your intake, this is a nutrition trend you may want to explore.

Next, check out 12 high-fibre foods worth adding to your cart.

Autumn in Ontario is a time to check off a hefty seasonal to-do list: admire the fall colours in a scenic country atmosphere, sample some cider, visit an apple orchard and gobble up all the apple-based desserts possible. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a one-stop-shop to enjoy all your favourite fall activities? Well, the Apple Pie Trail proposes a set path where you can achieve all your autumnal activity goals.

Following Ontario’s Apple Pie Trail

The 40-kilometre route known as the Apple Pie Trail is located in Ontario’s South Georgian Bay, which is the highest point of the Niagara Escarpment. The large bodies of water surrounding the region regulate temperatures and create the ideal microclimate for growing apples. Don’t let the name deceive you, though; the Apple Pie Trail is not only home to fruitful orchards, but also bakeries, restaurants, wineries and cideries, hiking and biking paths, and art galleries.

To kick off my Apple Pie Trail adventure, I headed two hours north of Toronto towards the Blue Mountains, where the promise of fall fun awaited via baked goods, adorable farm animals and cider tastings—and it sure didn’t disappoint. Although I only hit a few of the Apple Pie Trail’s 26 stops, I experienced a wide range of stunning sights and delightful bites along the way. A vehicle is a must when exploring the route, as stops are spread out on the country roads and it can take approximately 10-15 minutes to get from one place to another. To plan your itinerary, I’d recommend starting with the trail’s map, and basing your stops on your particular interests and the amount of time you’ve got available. I only had a day, so I wanted a general overview of what the trail has to offer—and the tourism office helpfully provided an assortment of the trail’s most popular stops. Next time, I would love to focus on one particular region or even try one of the curated experiences. With autumn officially here, perhaps you can choose your own adventure (and there’s even a trail app to help you plan it out).

Good Family Farms

My day on the Apple Pie Trail began on a sprawling, beautiful farm in Meaford, Ontario. Good Family Farms is over 400 acres and filled with cattle, pigs, and chickens, all raised with the utmost attention and care. It’s a lot of ground to cover, but luckily my tour guide showed me some of the key spots of the farm on an educational tour, in which I was shown around via tractor (a feature of the paid, bookable tour). In 90 minutes, I learned about the inner workings of the farm, from how the animals are raised, bred and fed to how the land is maintained. It was lovely to see how the farmers, animals and land work together in a sustainable way. Of course, there was also plenty of time to admire the adorable piglets and calves, and even pet some donkeys. On the way out, visitors can purchase organic meats and farm fresh eggs.

Looking for more fall fun? Here are 10 Ontario corn mazes worth getting lost in.

Blackbird Pie Company

The Apple Pie Trail’s namesake can be found at a few different points along the way, but Heathcote, Ontario’s Blackbird Pie Company is perhaps the best-known outpost for this fall dessert staple. Upon arrival, the smell of baked apples and butter tarts wafted out of the family-owned bakery’s doors before I even entered, and I knew I was in for a treat. They sell both fresh and frozen sweet and savoury pies, along with freshly baked tarts and pastries. I was told that, unsurprisingly, the classic apple pie and apple crumble muffins are some of their bestsellers, and after tasting a slice of the former, I understood why. The pastry crust is light and flaky, while the Northern Spy (known for its versatility in baking) apple filling is gooey and just the right amount of sweet. Warm it up and pair it with some vanilla ice cream for a heavenly apple pie experience. If you want to stray away from tradition, try one of their other fruit pies (wild blueberry, peach, and raspberry are all on the menu) or even a sandwich for lunch on their small but charming patio.

Georgian Hills Vineyards

Nestled in Clarksburg, Ontario, this peaceful and pretty vineyard offers so much more than just wine. Georgian Hills Vineyards marries offerings from their local grapes and apples to provide delightful wines and ciders (and literally marries couples, as a wedding and event venue). I was able to try five different wines from their substantial but manageable list, ranging from cider and sparkling wines to white, red, rose and dessert wines. As someone who prefers light and/or dry wines, I was extremely impressed by their Notty Bay line, which blends local, cold temperature grapes from Nottawasaga Bay/Georgian Bay into lovely easy drinkers. Post-tasting, I tried out a delicious vegetable and ricotta flatbread from their evolving patio lunch menu—they of course have wines and ciders listed on the menu, along with dessert options including a cheesecake trio and mousse. Personally, the flatbread sustained me but the temptation was there. Tastings and restaurant seatings can only be booked by reservation, so make sure you plan accordingly.

Discover more hidden gems in Ontario.

T&K Ferri Orchards

The next stop on the trail was just an apple’s throw away from Georgian Hills Winery. T&K Ferri Orchards is part of a legacy of apple growers spanning three generations and a few different locations, originating in Huttonville, Ontario. Karen Ferri, the co-owner of the orchard with husband Tom, tells me that the orchard, formerly in Brampton, Ontario, withstood a tornado and development pressures several years ago, before moving to Clarksburg. Ever the resilient growers, the Ferri grandchildren now grow an assortment of hand-picked apples in their vast orchard—we’re talking nearly 58,000 trees and 22 acres—ranging from Honeycrisp (their most popular) and Galas to Macs and Mutsus. Pick-your-own is not available at T&K, but visitors are able to purchase their apples of choice (along with non-alcoholic cider and cereal) and admire the carefully maintained orchard from afar.

Grey & Gold Cider

Grey & Gold Cider might be a relative newcomer on the Ontario cider scene, having established themselves in Clarksburg five years ago, but they are no rookies when it comes to crafting boozy goodness using local apples. Owner David Baker is a Toronto expat with a passion for creating unique ciders and a warm, inviting atmosphere. Grey and Gold’s cidery and bottle shop boasts a tasting menu of nine eclectic ciders, including medal winners Heritage Dry (gold) and Modern Girl (silver). My personal favourite? Probably a tie between the Wildflower, a chamomile-infused dry cider, and Spruce of the Bruce, a pine-forward dry cider that is surely a Christmas crowd pleaser. The surprises only continued after the cider tasting when I noticed a sign for “Goat Yoga.” Naturally, I had to meet the adorable baby goats kept on the premises. No downward dogs this time, but I may just have to make a trip out to greet the animals and have another glass of tasty cider.

Looking for another culinary road trip after you’ve tackled the Apple Pie Trail? Check out our guide to Ontario’s Butter Tart Trail.

A lot of thought goes into buying a new car, like what the interior and exterior features are, how the engine runs, and its safety technology. Perhaps the most enjoyable part of the process is deciding what colour you’d like your new vehicle to be. As it turns out, the colour you choose may be a factor of your chances of getting into an accident.

According to Kelley Blue Book, silver is the most popular car colour, with white as a close second. Of the two, however, white exceeds silver in its safety ratings, according to past research done by Monash University’s Accident Research Centre.

In accordance with the study, white cars are 12 percent less likely to get into an accident than black cars are, regardless of the time of day. Cream, yellow, and beige cars also ranked closely behind white.

Besides black, the most dangerous car colours are grey (11 percent higher risk), silver (10 percent higher risk), blue (7 percent higher risk), and red (7 percent higher risk).

Despite white being ranked as the safest car colour at any time of the day, all cars face a potentially higher crash risk when there is less visibility, such as driving in poor weather conditions or during nighttime hours. Believe it or not, there’s even strong evidence to suggest that Friday is the most dangerous day of the week to drive.

Next, check out our ultimate roadside emergency guide.

Walking. Hiking. Jogging. Biking.

Unaided, we can’t do any of these things without our feet. So why, when our quality of life is directly related to being active, do many of us ignore foot care?

Spanish scientists expressed concern over a rise in foot issues in their 2021 study of how poor foot health affects everything from physical activity to the overall health of able-bodied people (participants ranged from age 15 to 69).

“Foot problems can reduce quality of life, lead to loss of balance, make it difficult to put on shoes and increase the risk of falling,” the authors wrote in the journal Scientific Reports. “All of this can affect activities of daily living, including the desire to go outside.”

Meanwhile, a 2017 study, also in Spain, of able-bodied university students found that poor foot health not only prevented them from being physically active but also increased their risk of becoming socially isolated as a result.

Read on to discover how to practice good foot care.

Beat the bunion blues

If foot pain limits your activity and lasts more than a week, says Paul Langer, a Minnesota-based sports-medicine podiatrist, it’s time to see a podiatrist or an orthopaedist. Adds Hartley Miltchin, a Toronto podiatrist who has dubbed himself “the Bunion King,” if feet—the body’s foundation—aren’t performing properly, they throw everything else off. “They’re like the base of the Tower of Pisa. When they’re off, the tower leans.”

Bunions are one of the most common foot problems preventing people from being active. Almost a third of us have one. It’s the bony bump that can form when the big toe becomes misaligned; that causes the tip of the toe to move inward and the joint at the base to stick out sideways. Bunions don’t go away on their own.

Troy Gubb had always been active, but about a decade ago, in his early 40s, he developed a bunion on his left foot. When the Toronto-based manager for a communications and media company removed his skates after playing hockey, his foot was red and inflamed. After a round of golf, it throbbed. Eventually, he had to give up hockey, then golf, then running. He couldn’t even take Carl, the family bulldog, for a walk.

“The end of the line was last fall,” he says. “I was limping around with a cane and I couldn’t put pressure on my foot.” He began looking into how to deal with bunions.

The condition is generally caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and footwear, says Dr. Kathleen Gartke, senior medical officer at the Ottawa Hospital and an orthopaedic surgeon who has performed many bunion-removal procedures. “Fashion is not kind to feet,” she says, adding that wearing tight or narrow-toed shoes, high heels or shoes with no support is okay now and again, but “not all day, every day.”

If you notice a bony bump forming at the base of your big toe, try spending more time in shoes that don’t crowd your toes. Gartke also recommends wearing a toe spacer (available at most pharmacies) between your first and second toe to help keep them straight. It can also help you identify shoes that you shouldn’t wear—any that feel tight when you are wearing the toe spacer.

Bunions tend to worsen over time. If they become so painful that they interfere with your daily life, consider having them surgically removed. “All bunions are not created equal and so there are dozens of different procedures available,” Gartke says. “An X-ray will help your doctor decide on the one that best addresses your problem.”

The most common are exostectomy (or bunionectomy) and osteotomy, and they’re usually done in tandem. The surgery takes from 45 minutes to an hour. Exostectomy involves shaving off the bump of the toe joint. Then an osteotomy is done to solve the underlying issue. A surgeon makes cuts along the bone to realign the joint and inserts pins or screws to hold the bone in place. Sometimes a small piece of the big toe’s bone might need to be removed to help straighten the toe.

The good news is that the procedures often require only a local anaesthetic. And what was once a painful recovery can be better managed with a continuous nerve block. That’s when an anaesthetist puts a small tube into the back of the knee that delivers freezing into the nerve that connects to the foot in the bunion area.

“The tube can remain in place for a few days and provides excellent pain control,” says Gartke. Full recovery—when there is no more swelling or tenderness—takes from four to six months, depending on the procedure and the severity of the bunion.

Gubb had Miltchin remove his with a surgery the podiatrist developed that is quicker, less invasive and has a faster recovery time. He trains other podiatrists, as well as orthopaedic surgeons, in the procedure, during which he uses precision instruments to make small cuts in the bones to bring the big toe back into alignment.

Six weeks after his surgery in April 2022, Gubb was golfing again. By summer, he was running (and winning) races, and he returned to playing hockey and skating with his daughters a few months later. He only wishes he’d addressed his foot pain 10 years earlier.

Address other sources of foot pain

Apart from bunions, Langer says, the other common causes of foot pain that drive people to his clinic include plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis and osteoarthritis.

Plantar fasciitis is a stabbing heel pain common in runners and dancers. It is caused by inflammation of a band of tissue—the plantar fascia—that runs along the bottom of your foot, connecting your heel to your toes. It’s not a muscle, tendon or ligament, so it’s rigid and can’t stretch.

Over time, microtears develop on the tissue, causing pain. In people who overpronate (roll their heel inward when they walk), it’s worse because that creates even more tugging. Langer says that an off-the-shelf insole may help to relieve strain on the plantar fascia. If that fails, orthotics may be considered. Stretching, physiotherapy and icing the area can also help relieve symptoms.

Achilles tendinitis is an overuse injury that causes pain in the Achilles tendon, which connects your calf muscles to your heel bone. Resting and over-the-counter pain medications help, as do physio stretching and strengthening exercises. Orthotics that elevate the heel can also relieve strain on the tendon.

Another common culprit for foot pain is osteoarthritis, which is typically attributed to wear and tear. “One in six people over the age of 50 have arthritis in their feet, and, with 33 joints in each foot, that can be an issue that limits activity,” Langer says. Treatment includes medications (such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Advil and Aleve), physical therapy, cortisone injections or even joint replacement.

Check out more options to find relief from arthritis pain.

Keep your feet happy with foot care

Sometimes, foot care and the prevention of foot problems begins elsewhere in your body. Dahlia Fahmy, a physiotherapist and owner of Sports and Ortho Physical Therapy in Chicago, describes the body as “a kinetic chain.” Every move we make creates a chain reaction in our muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints.

“The foot is the driver of all movement,” Fahmy says. “When the foot hits the ground, everything else in the body changes, and if a foot is dysfunctional, it can drive everything up the chain to be dysfunctional, too.” The key to a healthy, stable foot, says Fahmy, is strength in the glutes and mobility through the hips and calves. “Our feet need help from their friends above to keep them working properly.”

Langer agrees, and frequently sends his podiatry patients exercise information and referrals to a physiotherapist to work on strength-training calf muscles, quads, hamstrings and glutes, as well as the upper body. He points out how important it is to strengthen the muscles of the foot and ankle. “Numerous studies show that having strong feet reduces our risk of falling and helps offset the natural deterioration of muscle that starts around age 50.”

Scientists at the University of São Paulo in Brazil concluded that strong feet can reduce your risk of running-related injuries by more than 50 percent.

To practice foot care and keep his own feet fit, Langer trains the large muscles in his legs and the small muscles in his feet with hill running and something called toe yoga. “The idea is to first activate the muscles of the foot, then progressively integrate the muscle activation into more challenging movements, like going from sitting to standing, then standing on one foot, then hopping, then running.”

A good pose to start with: Stand so your weight is evenly distributed between your big toe, pinky and heel. Then lift all five toes off the floor, spread them as far apart as you can, and then lay them back down, one toe at a time.

Langer, who has run more than 25 marathons, has long been fascinated by how our feet carry us through the world. “We don’t often think of our feet as sensory organs, but they send a tremendous amount of information to our brains to help us maintain balance, adapt to different surfaces and move efficiently.”

He compares what happens when we walk on a soft, sandy beach versus a concrete sidewalk: Sand is unstable and requires much more energy to move over than a firm, flat surface, such as concrete, he says, so “Our feet provide the sensory input that allows our brains to change the limb stiffness of our legs, helping us optimize our movement patterns for various surfaces.”

Walking outdoors has several health benefits for our feet, one of the most important of which, says Langer, is the variety of terrain. “Uneven terrain forces our joints to bend and flex to adapt, and it requires our muscles and neurologic system to work harder to provide power and balance.” All of this helps us maintain our range of motion, strength and balance—all part of practicing foot care.

So it was welcome news last year that Parks Canada joined PaRx, the country’s first national nature-prescription program: doctors can now prescribe time in national parks and conservation areas.

Regardless of the surface you do it on, walking offers myriad health benefits. Canadian researchers found it’s one of the best—and most preferred—forms of exercise for people with osteoporosis. Plus, a study published in September 2022 in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine analyzed activity-tracker data from 78,500 people and found that brisk walking for 30 minutes a day led to a reduced risk of heart disease and cancer.

Brush up on the proven benefits of walking.

Foot care includes choosing the right shoes

Despite research touting the benefits of extra cushioning, Langer says there is no magic shoe that is ideal for most people. One of the biggest mistakes people make, he says, is relying on reviews or salespeople for recommendations on the “best” shoes.

“Comfort is extremely important, but comfort is complex and can’t be quantified,” he says. “For example, I like a cushy—but not too cushy—forefoot and a wide, round toe box.” Trial and error, and gut instinct, are his secrets to successful shoe shopping.

Helen Branthwaite of the Royal College of Podiatry is a senior lecturer in clinical biomechanics at Staffordshire University in the U.K. She has based much of her research on her own passion for shoes and her interest in the impact they have on foot mechanics (sneakers are her favourite, though she does own a pair of heels or two).

“Research shows that shoes affect how we function,” Branthwaite says, “and influence our movement and how much pressure we put on our feet.” If shoes aren’t comfortable the moment you put them on, they’re best left on the shelf. “The concept that you can wear a shoe in, or that it will stretch, is nonsense,” she adds.

Branthwaite, who has a podiatry practice in Macclesfield, England, recommends that shoes match the shape of your foot. So if you have a square-ish foot, for example, look for similar-shaped shoes. And arch support is key. Some brands are developing styles to accommodate common foot issues, such as bunions.

Branthwaite also advises patients on what to wear to solve foot problems, whether it’s more cushioning for heel pain or smooth inside seams for bunion sufferers. “Sometimes the shoe becomes the treatment,” she says.

One of Branthwaite’s patients was suffering from such severe arch pain that she could no longer walk her dog, so Branthwaite had her replace her flimsy ballet flats with sturdy, supportive boots.

In 2021, French researchers studied the use of shoes specifically designed to improve balance and stability in everyone from athletes in training to people over 65. They noted that more than 30 percent of people older than 65 fall each year, and falls account for 90 percent of hip fractures. The researchers concluded that the shoes not only improved balance but made people feel safer and more stable when walking.

Gillian Parkinson, a retired speech and language pathologist in Wilmslow, England, can attest to the difference a change in footwear can make. Parkinson recently turned 70 and was finding walking increasingly difficult. She had developed Achilles tendinitis and was also rolling over on her ankles.

After a few unnerving falls, she went to Branthwaite for help. The first thing the podiatrist did was have Parkinson switch up her shoes (replacing slip-on loafers with shoes that had a Velcro fastening and a sole with more contact area to help with stability). Then she added a heel-raising insert so Parkinson would be better balanced.

Not only did her Achilles tendinitis disappear, but Parkinson began walking outside again, even tackling the occasional hill. “Within about 50 metres of our home, my husband and I can access a country lane. Or we drive to a historic site where we can walk for a couple of miles and reward ourselves at a little café at the end,” she says. “Therapeutically and psychologically, walking does me good.”

Now that you’re familiar with these foot care essentials, find out what happens when you start walking 10,000 steps a day.

In 1914, during the First World War, my grandfather Vernon C. Clark, like almost everyone 18 and older in those days, joined the Canadian Army to fight overseas. He was a small man and enlisted as a mechanic. When reporting for first line of duty, he mentioned that he was raised on a farm; he was assigned to the calvary because the line of thinking back then was: farm = horses. Horses were still used to move artillery in the Great War.

He was not pleased, as you could well expect, for two reasons: first, because he was a mechanic, not a farmer; and second, because the enemy would always shell the calvary first upon any major attack, as they sought to immobilize the artillery units during battle.

During one of his first stints of action, he was surprised to learn just how strong the attack of bombshells actually was, even after hearing all the stories. He fought in some of the biggest battles on the Western Front: Verdun, Vimy Ridge, Somme, and the battles of Ypres and Amiens.

Near the end of the war, as British and Allied forces slowly pushed back the German Army, the Germans made a surprise counterattack in hopes of delaying the Allied forces. The German artillery unit gave it all they had. Several shells landed very close to my grandfather’s unit; one even caused a piece of shrapnel to end up in his foot, something that would affect him for the rest of his life. He was taken to the infirmary, where it was confirmed his foot was so bad that he was proclaimed as no longer fit for duty, and subsequently sent home.

On the ship back home to Canada, my grandfather lay in the infirmary and was placed in a private area separate from all the other wounded. There seemed to be a nurse attending to his every wish. Many soldiers saluted him as they passed his bunk; he had no idea why. Plus, he was getting preferential treatment compared with the other wounded soldiers. This, too, was very puzzling to him. He was being given steak and wine with his meals and was always served before everyone else. No one was complaining about him being served first and he had a private nurse!

Finally, my grandfather asked the nurse why he was being treated like a king when so many others seemed to be much worse off than he was. The nurse looked at him like he was crazy and told him that this was the way they treated all Victoria Cross recipients.

You may be aware that the Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest military decoration that is or has been awarded for valour “in the face of the enemy” to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries and previous British Empire territories. It’s the highest of all the orders, decorations and medals. It may be awarded to a person of any rank in any service, as well as to civilians under military command.

The name tag on the bed that my grand father lay in read “Vernon Clark—VC” in stead of simply “Vernon C. Clark.” Someone had made a mistake with the sign!

He quickly realized that everyone must think he had been awarded the Victoria Cross, and he also realized that he had hit the jackpot! Suddenly his foot felt a whole lot better.

But soon, his conscience got the best of him. If you ever knew my grandfather, you would know that he was a very honest man. During his tour of duty, he witnessed atrocities of war that you and I could not begin to imagine. He saw how so many of the other wounded soldiers on the same ship were much worse off than himself. So when his next meal arrived exactly on time, as usual, he owned up to this error to the nurse. He told her that the name tag was correct but that someone had made a mistake in adding “VC” to the end—he had not been awarded the fabled Victoria Cross.

The nurse looked very surprised but then began smiling. She told him that they were almost at their destination of St. John’s, Newfoundland, therefore no one needed to be the wiser. So my grandfather continued to have his steak and wine and to be saluted vigorously by many higher-ranking soldiers. And although his nurse was not as attentive as she had been previously, she would often pass his bunk and throw him a knowing wink.

Vernon C. Clark lived to 94 years. As a result of that war injury, he had to wear a special shoe for most of his life. On his 80th birthday, he received the standard commemoration letter from then-Mayor of Toronto David Crombie, then-Premier of Ontario William Davis and then-Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, honouring veterans who’d fought in the great wars.

I have been telling this story every Remembrance Day since my grandfather, whom we called Poppa, first told it to me in 1974. (Of course, some of the details may have been slightly off, as there was a bottle of Dewar’s blended scotch whiskey on the table as Poppa told me the story.)

If you’re around me on the 11th of November this year, you may hear me retelling my grandfather’s Victoria Cross story once again. If so, please forgive me: It’s not a matter of me being boring; it’s simply that I was and still am so very proud of my grandfather Vernon C. Clark—a very brief holder of the Victoria Cross. I can’t begin to tell you how much I miss him, especially every November 11.

God bless you, Poppa.

Check out more Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.