For boys, messages about who they should be and how they should behave arrive early and remain insistent: Man up. Grow a pair. Don’t be so gay. The result is that being a young man oftentimes means trading off tenderness and connection for social status and approval.

Jake Stika, the 34-year-old executive director and co-founder of Next Gen Men, a non-profit focused on redefining masculinity for boys and men, knows this dynamic well. Back in 2007, during his second year at Brock University, Stika struggled with depression. To cope, he began binge drinking. Soon, he was getting into fights. At the same time, his friend Jermal Alleyne Jones was grieving the loss of his younger brother, who had been bullied and died of suicide. Together, and in conversations with friends, they realized just how toxic traditional ideas of masculinity could be for boys’ mental health.

“We wanted something different for the next generation,” says Stika. He, Alleyne Jones and another friend started Next Gen Men in 2014, beginning with a 10-week after-school program in the Greater Toronto Area. It landed on a simple but effective formula. Along with a recreational activity, like basketball or cards, the boys have facilitated conversations about gender equality, homophobia, bullying, mental health and healthy friendships.

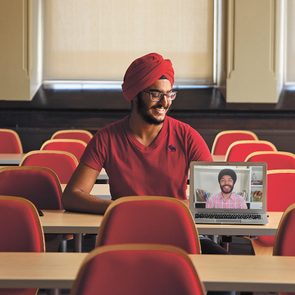

“There is a myth that boys and men don’t want to open up about their feelings,”says Stika.“The truth is they aren’t invited to have these conversations.” One of the key lessons from these early groups, he adds, was that boys were eager to talk. Pre-pandemic, Next Gen Men offered after-school programs across the GTA, facilitated by youth program manager Jonathon Reed. The programming has since moved online. Stika estimates that more than 2,300 boys have participated.

Twelve-year-old Mateo is a current participant. Another boy had felt picked on by Mateo and asked Reed to invite him to join the program. Mateo agreed and the two worked through their conflict by having conversations both individually with Reed and together. The boys have since become “pretty close” friends, says Mateo, bonding over games like Fortnite and Minecraft. For Mateo, it was also a chance at a fresh start. He liked that Reed didn’t judge him. “Jonathon didn’t think I was bad,” he says, “just that I could do better.”

That kind of individual transformation is a central pillar of NGM’s work: to support boys in building empathy and in learning to communicate and care for themselves and one another. Most participants are between ages 11 and 14—research indicates that adolescence is when children form their own values and identities. It’s also when there is often a rise in bullying, racism, misogyny and homophobia in social interactions.

“There are narratives in media and culture that boys have power, or will have it. But when you’re 12, you don’t feel you have power,” Stika says. “So often boys enact what little power they have through differentiation,” that is, by picking on others and jockeying for social status. NGM disrupts this by offering alternative, healthier versions of masculinity. And their work doesn’t stop after a certain age, either.

Shortly after NGM started, Stika’s friends told him they wished they had groups like his when they were kids. In response, NGM began hosting gatherings for adults of all genders. More than 2,000 people have since participated across five Canadian cities, including Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. This year, NGM plans to get even bigger and will soon start a development program for educators called Next Gen Mentors. For Reed, it’s all part of a revolution: “What could it look like for this light bulb moment not just to happen for one boy, but for a whole community?”

Find, out out how a Toronto-based charity uses art to fight homelessness.

Fingernails seem like a pretty uneventful body part. They grow. You cut them. Maybe paint them. And that’s about it. But in reality, your nails can give you a glimpse into your overall health. If something is going on in your body, your nails could start to change, sometimes developing ridges. Depending on what the ridges in fingernails look like, you might want to schedule a visit to the doctor.

Vertical ridges

Lines running from the bottom of the nail to the tip are the most common form of ridges in fingernails, affecting about 20 per cent of adults. In the vast majority of cases, it’s just a sign of aging, says Ivy Lee, MD, a board-certified dermatologist based in Pasadena, California. Fingernails are made mostly of keratin, a protein also found in the hair and outer layer of skin. In the same ways that the skin gets drier and the hair feels rougher, the nails also change with age because the body has a harder time retaining moisture.

But if you see other changes in the nails, like splitting or a colour change, you might want to consult a doctor, says Dr. Lee. In rare cases, ridges in fingernails could be a sign of anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, or cardiovascular problems. A single ridge in the middle of the nail, for instance, could be a sign of a nutrient deficiency like protein or folic acid. (Learn to spot more silent signs of anemia.)

Horizontal ridges

Ridges in fingernails that run side to side are less common and might give you more pause. Also known as Beau’s lines, they could signal disease or just be a remnant of an old injury, says Dr. Lee. “They arise because there is a temporary stop in nail growth in the proximal nail matrix, where the fingernail is made,” she says. “They are most often benign and due to mechanical trauma: manicures, jamming your finger in the door, etc.”

Sometimes, though, they point to a skin disease like eczema, psoriasis, or chronic paronychia (an infection of the nail folds that makes the skin swollen and red), so inspect your skin and fingertips for signs of redness and rash. Your dermatologist might be able to offer a treatment option.

But it’s not all about the skin—ridges in nails can also be a sign of other systemic problems. For instance, an over- or underactive thyroid can affect the hormones in charge of nail, skin, and hair growth, resulting in ridged nails in some cases. If all 20 finger- and toenails develop Beau’s lines at the same time, it could even be an infection like pneumonia, mumps, or syphilis, or a problem with the heart, liver, or kidneys. Particularly if your ridged nails have also become thinner, split, discoloured, or misshapen, schedule a visit with your dermatologist pronto to get to the bottom of the problem, says Dr. Lee.

Next, find out 20 symptoms you should never ignore.

The wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer is no doubt one of the most memorable events in the history of the British royal family. It ushered in the age of the People’s Princess, as Diana broke down barriers between the royals and the public and became “a queen of people’s hearts.” And it debuted her iconic wedding dress that, until then, was considered “the most closely guarded secret in fashion history.”

But that secret actually has a rival: a second, secret wedding dress that Princess Diana never even tried on.

The Wedding Dress Princess Diana Never Wore

You already know what the actual wedding dress looks like. The ivory taffeta gown designed by Elizabeth and David Emanuel featured elegant embroidery, antique lace, 10,000 pearls, and an impressive 25-foot-long train. Possibly more impressive, the sought-after designs for the dress managed to stay confidential until the day of the wedding. The husband-wife design team also made an exact duplicate of this dress to be put on display at Madame Tussauds.

Yet there was a third dress in the mix that few knew about until Elizabeth Emanuel revealed the truth to PEOPLE in a 2011 interview. She told the magazine that they had made a backup dress in case of an emergency, such as if the designs for her real dress had been leaked. “At the time we wanted to make absolutely sure that the dress was a surprise,” she said.

“We didn’t try it on Diana. We never even discussed it,” Emanuel added. “We wanted to make sure that we had something there; it was for our own peace of mind, really.”

Similar to the original, the third dress was an ivory silk taffeta gown that had the same ruffles around the neck, but no lace. However, it was never finished.

“It was only three-quarters finished,” she told the Daily Mail in a 2017 interview. “We simply didn’t have time to make it in its entirety, so none of the embroidery or finishing touches were done.”

And the secrets keep on coming. Not only does this mystery dress exist, but now no one knows where it is. Not even Emanuel herself. According to her, it hung in their studio “for a long time,” and then seemingly vanished without a trace. (Here are 15 facts you never knew about past royal weddings.)

“I don’t know if we sold it or put it into storage. It was such a busy time,” Emanuel told the Daily Mail. “I’m sure it’ll turn up in a bag one day!”

Until that mystery gets solved, all we can do is mimic Emanuel’s optimism and hope that one day, we too will see The Wedding Dress Princess Diana Never Wore.

Next, check out 40 little-known facts about the wedding of Prince Charles and Princess Diana.

Kat Palmer was in Grade 9 biology when she began to doubt everything. The day’s lesson was on basic genetics and her teacher explained that the odds of two blue-eyed parents giving birth to a brown-eyed child were extremely remote. When she got home, Palmer broached the topic with her mother, Janet, who always knew this moment was coming. In the late 1980s, Janet and Kat’s father, Lyon, had wanted, very badly, to have a baby, but biology refused to cooperate. The Palmers, who lived in Ottawa, were thrilled to book an appointment with Dr. Norman Barwin, a local fertility specialist known as the “Baby God.” Out of a selection of possible donors, the Palmers chose a German-Irish medical student who played cello. Kathryn Rose Palmer was born on January 31, 1991 with coffee-bean eyes, a thick tuft of dark hair, and a determined jawline that everyone said looked like Lyon’s.

Kat and Lyon had always been close. So while she was shaken by her mother’s revelation, she decided this wouldn’t fundamentally change her relationship with the man who raised her. At the time, she didn’t have much interest in learning anything more about the sperm donor.

Mostly she didn’t think of him at all, though she did start to make little connections: her love of the performing arts and her talent as a musician (Kat would later study at Victoria’s Canadian College of Performing Arts) must come from her cello-playing bio-dad. “I had no idea that I was building my identity around a lie,” she now says.

A lie that, once uncovered, revealed a decades-long deception. It wasn’t until 2014 that the Palmers learned Janet was one of more than 100 women who had been impregnated at Barwin’s clinic with the wrong sperm. In some cases, the specimens came from men who were not the agreed-upon donor; in other cases, from the Baby God himself.

In 2016, Kat Palmer was among the first claimants to join a class action lawsuit against Barwin. By the time the unprecedented, $13.375-million settlement was reached last November, it included 226 plaintiffs (including children, mothers, partners and donors). The settlement is believed to be the first of its kind and could establish a precedent for similar civil charges. But it doesn’t address the systemic failures that allowed Barwin to practise, largely unfettered, for nearly 40 years. And it does nothing to appease donor-conceived Canadians who say the Barwin case highlights a culture of secrecy that denies them basic rights. The case also raises troubling questions about a medical establishment that prioritizes the interests and reputations of physicians over the needs of patients. Like Palmer, children conceived at Barwin’s clinic are left to wonder about the motivations of a doctor whose deity status obscured a devastating reality.

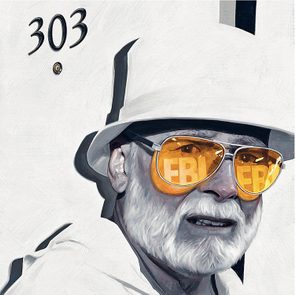

When Kat first found out that Lyon Palmer wasn’t her biological parent she didn’t think that DNA mattered. Today she feels differently: “Of course DNA matters. If it didn’t, this whole situation never would have happened in the first place.” And she’s right. Many aspiring parents challenged by infertility dream of shared genetics: the same deep-set gaze or determined jawline. Barwin’s ability to outmanoeuvre Mother Nature kept him in constant demand. Between the mid-1970s and the late aughts, he impregnated hundreds of women using artificial insemination. His success rate (Barwin claimed 76 per cent with fresh sperm and 63 per cent with frozen) spoke for itself. If that success bred a sense of imperviousness, it was hard to recognize under the white coat and soft-spoken, gentle veneer.

Who is Dr. Barwin?

Born in South Africa, Barwin earned his university degree and married his wife, Myra, before moving to Northern Ireland to complete his medical training. In Ireland the couple had four children and, in 1973, relocated to Canada, drawn by its progressive reputation and the offer of a job running the high-risk pregnancy unit at Ottawa General Hospital. But he left that position in 1984 after failing the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada gynecological exam multiple times. From there he launched his private practice, the Broadview Fertility Clinic, bringing many of his loyal patients with him.

Barwin was politically engaged, at the forefront of reproductive rights and an advocate for LGBTQ communities long before the medical establishment had come on board. In the early ’70s, he was among the first to perform gender- affirming surgery and contributed to some of the first ever textbook chapters on this emerging science. In the late ’70s, he set up the first sexual health clinics in Ottawa’s public high schools. His four children decorated an old school bus— the “Sex Bus”—which drove around Ottawa distributing information on sexual health and anti-smoking. In 1988, he campaigned against Bill C-43, which would have seen abortion added to the criminal code. He also served as president of Planned Parenthood and of the International Society for the Advancement of Contraception. A glowing 2001 profile in the Ottawa Citizen described Barwin, in an inadvertent foreshadowing of the revelations to come, as a physician who “believes in doing whatever he feels is necessary to help his patients, regardless of taboos or conventions.”

In 1995, a couple named Loree-Ann Huard and Wanda Cowton sued Barwin when they found out their daughter was not a genetic match to their intended donor. The case was settled privately in 1998, a year after Barwin was awarded the Order of Canada and praised for his “profound impact … on both the biological and psycho-social aspects of women’s reproductive health.”

Also in 1995, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), the self-governing body responsible for overseeing the conduct of doctors, contacted Barwin about the Huard-Cowton complaint. He responded that he had taken steps to ensure such errors would be avoided. If that is true, the measures weren’t successful.

In 2008, another former Barwin patient, Trudy Moore, learned her daughter (born by surrogate) was not a genetic match to the intended donor (her husband). When Moore asked Barwin for an explanation she was told that her husband’s sample may have been contaminated by a sample from a sperm bank. She consulted the Donor Sibling Registry, which connects individuals conceived with the same genetic material, and was referred to Jaqueline Slinn, a former Barwin patient who was also under the impression that her daughter, Bridget, was conceived using the same sperm bank donor. Expecting their daughters to be genetic half-sisters, the two mothers tested their DNA only to learn that the girls weren’t related. Nor was either girl a match to other children conceived ostensibly using sperm from that donor. Moore and Slinn filed two separate $1-million lawsuits against Barwin: the former for malpractice and the latter for information regarding the donor, including a genetic sample from Barwin to rule him out as a potential father.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail, Barwin called the situation “my worst nightmare,” and claimed he was still “unable to find where the basic problem lay.” Both lawsuits were settled out of court and included non-disclosure agreements. In 2012, the CPSO ordered a disciplinary hearing. The following year, Barwin was found guilty of professional misconduct. The chair of the five-member panel described his “substandard failure to establish adequate safeguards,” suspended his medical license for two months and charged him $3,650 in costs—in other words, a wrist slap. But the publicity surrounding the hearing would capture the attention of a whole new group of Barwin’s victims, including Kat Palmer.

DNA Revelations

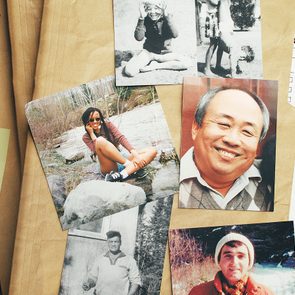

By 2012, Palmer had moved to Vancouver, where she worked in musical theatre. She still wasn’t particularly interested in meeting her birth father, but she was very curious about potential half-siblings. As an only child she had always dreamed of having a brother or sister. One day she broke down in tears watching an Anderson Cooper talk show about uniting long-lost siblings, and took this as a sign that it was time to do something. When she contacted Barwin’s clinic to learn more about the mysterious donor, she was told that, in accordance with provincial regulations, the clinic destroyed records after 10 years. Undeterred, Palmer sent a DNA sample to Family Tree DNA, one of many commercial genetic testing sites that have gained popularity over the last decade. She hoped the results would help her find siblings who shared her Irish-German donor. But when the results came back, she learned that she was almost certainly of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. For a brief moment, Lyon Palmer (who is Jewish) thought that perhaps, miraculously, he was the biological father. But further testing ruled this out.

Family Tree DNA did connect Palmer with relatives, all several degrees removed, which is how she ended up speaking on the phone with a third cousin. Palmer mentioned that she had been conceived at a clinic run by Dr. Norman Barwin. When the cousin later mentioned this to his mother, she paused, feeling the name sounded familiar. A quick record search comfirmed she had a distant relative named Norman Barwin.

Long before any of these revelations, the Palmer family had known Barwin socially. It was impossible to be a member of Ottawa’s Jewish community and not be aware of Barwin and his good works. Kat had even taught one of Barwin’s grandchildren at an after-school theatre program.

That her pupil might, in fact, be her niece was something Palmer was beginning to process. She started to follow Barwin’s family members on Instagram, marvelling at physical similarities and how many worked in the arts. Her urge to connect with these people— her biological family—felt somehow more important than whatever anger she felt towards Barwin.

On August 13, 2015, Palmer sent an email to Barwin: “I am writing this letter because I have found information that makes me believe that I am, genetically, your descendant.” He wrote back immediately and soon the two spoke on the phone. During their conversation, Barwin agreed to a DNA test. Palmer isn’t sure why he was so quick to hand over the genetic smoking gun. “I think I seemed so non-threatening. And then at the same time, I had him backed into a corner.”

When the test confirmed that Barwin was Palmer’s biological parent, he attempted to explain the situation. He had purchased new equipment in 1990—perhaps it had been contaminated during testing. Palmer thought that sounded implausible but wanted to avoid conflict in the hopes of connecting with her half-siblings. That hope was dashed when Barwin explained that learning of Kat’s existence would be too difficult for his wife and four children, and his dozen-plus grandchildren, all of whom lived in Ottawa. He sent Palmer an email: “My compensation for this inadvertent medical error is that you have been so successful in your career, but more importantly that you are a sensitive and special person.”

To Palmer, the response was a rejection, and also deeply narcissistic—like he was taking credit for her positive traits. She contacted Trudy Moore, whom she’d read about in media coverage of the 2013 disciplinary hearing.

Moore referred her to the law firm Nelligan O’Brien Payne LLP, which was preparing to launch a class action suit against Barwin. The suit accused him of using, without consent, the wrong semen for artificial insemination, and failing to safekeep semen entrusted to him. The main plaintiff was Rebecca Dixon, a 25-year-old civil servant who lived in Ottawa. She learned Barwin was her biological father after she was diagnosed with an autoimmune condition that doesn’t run in her family.

After being connected by their lawyers, Palmer and Dixon began texting almost daily. Their bond was immediate—they discovered they had attended the same Ottawa high school, that they both talk with their hands and love music. Four months later they met in person at Pearson International Airport. Palmer ran out from behind the arrivals door. Dixon held a sign that read “Welcome Sister” in multicoloured bubble letters, and the two women attempted to make up for more than two decades of lost hugs in one epic embrace.

Palmer and Dixon soon learned about a half-brother, James, and a half-sister, Marie, plus 24 others, ranging in age from 30 to 50-plus. Some have connected through the class action lawsuit, others through genetic testing. The group jokes that they need to brace themselves for more siblings after Christmas, when DNA kits are often given as gifts. Last summer, 30 of the half-siblings gathered at Dixon’s home for an atypical family reunion. “The relationships we have developed are amazing,” says Palmer. “But that doesn’t make what happened okay.” She gets angry when people act like nothing bad happened. Can’t you just be grateful you’re alive?

It’s a conundrum, but not one Dixon is willing to spend a lot of time with. “You can think about it in circles forever,” she says. “Or you can just accept that I can be happy that I’m alive and that what he did was a terrible thing. Both things can be true.”

Does This Happen Often?

Fertility fraud is shockingly common. Dr. Donald Cline, the Indiana fertility specialist and subject of the recent Netflix series Our Father, impregnated more than 50 women with his own sperm in 10 years. Dr. Quincy Fortier of Las Vegas used his own sperm to impregnate at least 24 patients from 1950 to the late 1980s. In 1992, Dr. Cecil Jacobson of northern Virginia was convicted on numerous counts of fraud and perjury for inseminating unwitting patients with his own sperm.

“It’s not that it is happening more, it’s that we are able to catch it,” says Sara Cohen, a Toronto fertility lawyer. The rise of commercial DNA testing and donor-conceived sibling registry websites has brought a previously difficult to detect misdeed into the foreground. At the dawn of artificial insemination in the 1940s, record-keeping was not the norm. Doctors would often solicit “donations” from medical students. Prospective parents were happy to get “future doctor” sperm and the thinking was that the lack of a paper trail between donor and child was best for everyone involved. Although not officially sanctioned, doctors using their own sperm was common enough that two percent of American fertility doctors said they engaged in the practice in a 1980s survey.

In the early ’70s, when Barwin established a sperm bank at Ottawa General Hospital, he made no secret of the fact that it was largely stocked by his medical students (he said nothing about using his own sperm). By the time he opened the Broadview Fertility Clinic in the mid-1980s, the culture was beginning to change. With artificial insemination now a mainstream practice, a regulated sperm bank industry emerged to serve a growing market.

Did Barwin freeze his own samples? Or did he produce live sperm (known to be slightly more effective) in the short window before an appointment? Were his decisions guided by negligence? Malice? A misguided sense of benevolence? These are the questions that haunt Palmer, but she believes she and the other Barwin descendants are, in some ways, luckier than many of her co-plaintiffs who haven’t been able to track the identity of a biological father. “It’s not the answer we want,” she says, “but at least we have one.”

What’s Being Done To Prevent It?

In 2004, Canada passed the Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHRA), regulating how donated sperm is tested and processed, but a constitutional challenge by the Province of Quebec has resulted in a stalemate, and it remains unclear which level of government has the authority to regulate assisted reproduction. Meanwhile, compliance is, at best, spotty. “There is a joke in the donor-conceived community that it is hard to find a clinic that hasn’t had a fire or a flood,” says Kevin Martin, co-founder of the Donor Conceived Alliance of Canada. Donor-conceived individuals face a frustrating battle when looking for their biological information. The organization is pushing the government to update the AHRA with requirements for expanded donor health screening, record-keeping for up to 110 years, limits on how often a single donor can be used and, above all, a ban on donor anonymity. The thinking there, Martin explains, is that a donor-conceived individual’s right to their biological information should outweigh a donor’s right to anonymity. I ask Martin how rules around anonymity would have made a difference with Barwin—it’s not like he would have written his own name on the form. Martin says that it’s about deception thriving in dark corners: “Anonymity is what allowed Barwin to do the things he did, to lie and obfuscate with zero accountability. Anonymity is how this happened. Transparency is what can fix it.”

Indeed, a culture of silence could explain how Health Canada inspected Barwin’s clinic in 1999 and 2002, and found numerous infractions, including mishandled and missing sperm. Despite this, he wasn’t shut down. Worse, the CPSO claims it was never made aware of these findings.

Paul Harte, a medical malpractice lawyer, argues that the self-governing College system for doctors is inherently biased. “There’s a tendency to protect your own,” he says. Harte would like to see the introduction of an independent body similar to the Securities Commission. The Barwin case, he says, is a good example where you have, on one side, a very vulnerable group (people struggling with infertility) and then on the other side a significant financial incentive. “Inevitably there is going to be a certain amount of corner-cutting to ensure success,” he says.

Many experts believe that classifying fertility fraud under the criminal code is an important step towards justice in Canada. In the United States, some states have created laws against it. Texas, for instance, made insemination with sperm the patient did not consent to a form of sexual assault.

What Now?

Norman Barwin retired in 2014. After investigating complaints that Barwin had used the wrong sperm, or his own sperm, at his clinic, the CPSO revoked his medical license in 2019 and fined him $10,730. Barwin pled no contest to the allegations. Last November, an Ontario Superior Court judge approved the agreed-to $13.375-million settlement from the class action suit, which included 17 plaintiffs who were conceived using Barwin’s own sperm. The settlement will be paid out by the Canadian Medical Protective Association, which represents doctors subject to legal actions. Because the case was settled out of court, Barwin made no admission of wrongdoing and offered no explanation.

There is this story, though: In 2000, Barwin, a life-long runner, competed in the Boston Marathon, finishing 14th in his age group. Later inspection revealed that he had missed check-points and had cheated his way to a strong finish. The incident was covered by Ottawa media, with many of Barwin’s former patients coming to his defence. But the following year, he was caught cheating again at the National Capital Marathon in Ottawa, the behaviour of a man for whom the rules simply do not apply.

When Palmer and Dixon first learned the truth about their conception, they asked themselves if they were the products of one man’s deranged plot to populate the earth with his descendants. Now they are more inclined to see the story, their story, in shades of grey. The man who is responsible for their existence was a doctor who would do anything for his patients up to and including things to which those patients would never consent. He was a champion of women’s rights who also violated the rights of women in the most intimate and offensive ways imaginable. A “Baby God” and a monster. And while there is an inclination to see these dichotomies as either-or, for the people who share Barwin’s DNA it is perhaps better, and easier, to believe that both things can be true.

Next, check out 10 Canadian true crime podcasts worth adding to your playlist.

Princess Diana was in a desperate situation in 1995. Her marriage to Prince Charles was unravelling over his affair with Camilla Parker-Bowles, she had been in love with another man herself, and she was questioning the role of the monarchy in modern life.

But when she revealed those shocking details during an interview with television journalist Martin Bashir, viewers were gobsmacked that a member of the buttoned-up royal family would divulge such information to the world.

As it turns out, Princess Diana may have been encouraged to speak out by another member of the royal family: Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York. That’s according to one of Diana’s close friends, Simone Simmons, who was interviewed for the Amazon Prime documentary, Diana: The Woman Inside.

Simmons said Diana called her after the interview and encouraged her to see it—before Diana had the chance to watch it herself. “She was very pleased with what she’d done at the time, she thought it was a great performance and she was thrilled,” royal biographer Penny Junor told the International Business Tribune. “She rang up her friends and said, ‘you must watch.'” Diana said she thought the piece would focus on her charity work.

But the interview that aired showed a tearful Diana revealing that “there were three people in this marriage.” She was referring to Prince Charles’s longtime love for Camilla Parker-Bowles. (Here’s why Charles didn’t marry Camilla in the first place.) Diana and Prince Charles were separated at the time, and she admitted that she had an affair with cavalry officer James Hewitt. She also questioned her estranged husband’s fitness to be king.

Simmons recalled she didn’t hold back with her friend, telling her that she thought she had made a “prat” out of herself. Flabbergasted, she asked Diana who encouraged her to give the interview. Diana told her it was Fergie (a nickname for the Duchess of York) and another friend.

Apparently, Diana and Fergie had a complicated relationship, according to Town and Country. Distant cousins, they had been friendly before they married into the royal family. Diana sat the fun-loving Fergie next to her brother-in-law, Prince Andrew, then an eligible bachelor, at a dinner. Fergie later married Prince Andrew, but both she and Diana often felt alienated within the royal family.

Once Diana saw the interview, she was reportedly horrified by it. The next year, her divorce from Prince Charles was finalized. Then in 1997, Diana died after a car crash in Paris. One of her close aides later revealed that Diana “deeply regretted” what she said in the Bashir interview.

So what did Fergie think about the Bashir interview? On The View in 2003, she said Bashir “tricked” Diana into revealing the information.

“He lulled her into a comfort zone by being this wonderful magnanimous man and by saying ‘I’m a family man as well’ and got her to talk that way,” Ferguson said, according to the Guardian. “And, of course, ‘off the record’ doesn’t exist.”

Find out more of what Sarah Ferguson revealed in her shocking royal memoir.

Considering that he’s sixth in line for the British throne (even after “stepping back from royal duties”), it’s safe to say that Prince Harry will probably never get to be the king of England. But were the line of succession not a factor, would he make a good ruler? Harry’s own mother, the late Princess Diana, reportedly thought so—in fact, she thought he would actually be better suited to the throne than Prince William.

In her 2018 biography Harry: Conversations with the Prince, Angela Levin delves into Harry’s relationship with his mother. According to Levin, as Diana’s sons grew up, she identified qualities in Harry that she thought would make him a good, willing ruler. Even though William was older, and, of course, the actual heir to the throne, she thought it was Harry who possessed more qualities that befitted a leader, including his “ability to cope,” “ease with people,” and “general gusto.” Reportedly, Diana even gave her younger son the nickname “Good King Harry.” (Check out these rarely seen photos of Diana and Harry.)

As for William, Diana didn’t necessarily think he wasn’t suited to be king. But she did sense that her older son didn’t want the throne, so much so that she would “worry about” how he’d bear his future kingly burden. “William doesn’t want his every move watched,” Levin quotes Diana as saying.

Of course, though, this was when William was much younger, so will he make a good king when he inherits the throne one day? We probably won’t know for many years.

Next, check out the most shocking royal memoirs ever published.

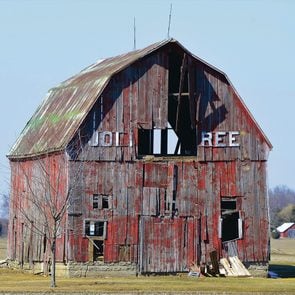

My husband Colin has always been a farmer at heart. He grew up in the small town of Hardisty, Alberta, but spent many days out on his great-uncle’s and his grandparents’ farms, helping out from a young age. We still reside in Hardisty and for the last 12 years, we’ve lived on a three-acre lot. Recently, Colin purchased a 70-year-old Allis-Chalmers tractor from a good friend. It was in running order but had done little but sit and look pretty. Colin was in his glory when he took it off his friend’s hands. He uses it on a daily basis, even if it is only to drive in circles around the acreage or pull our mobile chicken coop from one spot to the next. He’s also dug out an old John Deere cultivator at his grandfather’s homestead and tried to use the almost 90-year-old piece of equipment to cultivate our garden! It still works—with a little bit of extra elbow grease.

Colin is now busy teaching our sons, Braxton and Brayden, about the history of farming in hopes that they too will appreciate what our grandfathers and great-grandfathers once had to do to live in this beautiful country. He takes the boys out to his uncle’s and cousin’s farms to help out with combine harvesting in the fall, working the cattle and sometimes helping with calving. Braxton and Brayden are both fascinated with farm life and the machines. Colin likes to talk about what his grandparents used to do on the farm and he loves the vintage tractors—they are simple, less electronic contraptions that are less likely to break down. One day, this old tractor will get a new paint job, but in the meantime, it’ll be cranked and enjoyed for many years to come!

Next, check out the true story of Ontario’s farmerettes—Canada’s forgotten wartime heroes.

On August 30, 1997, Princess Diana called to check on her sons Prince William, 15, and Prince Harry, 12. The boys were vacationing in Scotland with family while Diana was on a summer getaway in France with her boyfriend, Dodi Fayed. But as kids can be, a phone call with their mum paled in comparison to playing with their cousins. “Harry and I were in a desperate rush to say goodbye, you know, ‘see you later,’” Prince William said in a film interview. Little did the princes know that it would be the last time they’d ever hear their mother’s voice. Shortly after midnight, Diana died in a tragic car accident.

Twenty years later, in the 2017 documentary, Diana, Our Mother: Her Life and Legacy, the two princes reflected on the regrets they have about that very phone call mere hours before their mother’s death.

“If I’d known now what was going to happen, I wouldn’t have been so blasé about it,” Prince William told the filmmakers. “But that phone call sticks in my mind quite heavily.”

The pangs of guilt and regret still eat away at his younger brother as well. “Looking back on it now, it’s incredibly hard. I’ll have to sort of deal with that for the rest of my life,” Prince Harry said in the documentary. “How differently that conversation could have panned out if I’d had even the slightest inkling her life was going to be taken that night.”

Despite their anguish about taking the last chat with their mother for granted, the boys continue to keep Princess Diana’s legacy alive. In fact, Prince William will often gush about his mother to his children as he tucks them away in bed. He even has them call her the sweetest name – Granny Diana. “Just to remind them that there were two grandmothers in their lives,” Prince William said in the interview.

Next, take a look back at these rarely seen photos of Princess Diana.

After a tumultuous 15-year marriage filled with scandal, Princess Diana and Prince Charles divorced in August 1996. Fortunately, the divorce did not strip Diana entirely of her fortune and status. Under the divorce agreement, she shared parental custody with Prince Charles raising their two sons, had full access to the royal family jets, and could keep her Kensington Palace apartment as long as the Queen agreed, along with all of the jewelry she obtained during her royal marriage. It was also reported by London newspapers that Diana would get $600,000 a year to maintain her new private offices in Kensington Palace, in addition to $22.5 million in cash, but official details of the financial settlement remained under wraps.

Even though it sounds like Diana had a pretty cushy settlement compared to most divorced spouses, there may have been one catch to some of the terms of the agreement—her marital status. In fact, royal family experts believed she may have had to relinquish many of her divorce settlement benefits if she were to remarry. She reportedly could have lost her home in Kensington Palace, the financing of her office, and possibly her title as “Princess of Wales” if she said “I do” again.

One thing she did lose upon her divorce? Her “Royal Highness” title, which was the one thing she wanted to remain intact. A royal behaviour expert told the New York Times in 1996 that stripping the “Royal Highness” from Diana’s name was “without historical precedent.”

As for what would have happened to Diana’s royal standing if the “people’s princess” had wed for the second time, unfortunately, none of us will sadly ever know, since her tragic death came a year after her divorce was finalized.

Next, discover 40 little-known facts about Charles and Diana’s wedding.

After being advised by friends to ignore suspicions of an affair between her husband Prince Charles and his long-time friend Camilla Parker Bowles, Princess Diana felt that she had to give her husband’s mistress a piece of her mind, according to archived recordings from National Geographic.

The Confrontation Between Camilla and Diana

Diana knew what she was getting herself into when she approached Camilla about the affair, and apparently so did Prince Charles. Camilla and Prince Charles were chatting with another friend in a downstairs room when Diana asked to have a moment alone with Camilla. According to the recording, Diana remembered Charles frantically running upstairs asking the friend what Diana was going to do.

Although the Princess of Wales said that she was “terrified” of Camilla, Diana told her boldly, “I’d just like you to know that I know exactly what is going on.”

Camilla attempted to avoid the claim by saying she did not know what Diana was talking about. Diana remembered Camilla saying that she had “everything she could ever want” and “all the men in the world.” When asked what more she could want, Diana told the Camilla, “I want my husband.”

Oddly enough, Diana apologized to Camilla for being in the way of her and Charles, but she was still outraged. “I do know what is going on,” she said to Camilla. “Don’t treat me like an idiot.”

A fool Diana was not, because by 1994 Charles admitted to his adultery, and in 1996, the couple filed for divorce. As we all know, Prince Charles eventually married Camilla in 2005.

Next, check out the most controversial royal memoirs ever published.