My pal Bosco the Bear

I met Bosco in the remote wilderness near British Columbia’s Mount Robson. At the end of a long day of backpacking, I had made a lean-to in a clearing beside a stream and was preparing to catch supper. Then I looked up, and there he was: an enormous black bear, slowly circling the clearing within 30 yards.

He wasn’t Bosco to me yet, and I viewed his presence with trepidation. My provisions were vulnerable if he was in a piratical mood, since I was unarmed. However, I decided to go about my fishing. The bear came along.

I’ve lived with wild creatures for 30 years, always respecting their first fear—fast movements—so I let the bear see every slow, deliberate move I made. Soon he was sitting on his haunches less than five feet away, intensely interested in my activity. When I landed a 35-centimetre Loch Leven trout, I tossed it to him. He gulped without bothering to chew. And when I flipped out the fly again, he moved closer, planted his well-upholstered fanny on the turf beside my boot and leaned half his 225 kilograms against my right leg!

When drizzly darkness set in, I was still fishing for that bear, fascinated as much by his gentle manners as by his insatiable capacity. I began to think of him in a friendly way as Big Bosco, and I didn’t mind when he followed me back to camp.

After supper I built up the fire, sat on the sleeping bag under the lean-to and lit my pipe. All this time Bosco had sat just outside the heat perimeter of the fire, but the moment I was comfortably settled he walked over and sat down beside me. Overlooking the stench of wet fur, I rather enjoyed his warmth. I listened to the rain thumping on the tarp in time with the steady, powerful cur-rump, cur-rump of his heartbeat beneath his thick coat. When smoke blew our way, he snorted and sneezed, and I imitated most of his body movements, even the sneezing and snorting, swaying my head in every direction, sniffing the air as he did.

Then Bosco began licking my hands. Guessing what he wanted, I got him a handful of salt. He enthusiastically nailed my hand to the ground with his two-inch claws—claws capable of peeling the bark from a full-grown cedar, claws that carried his 225 kilograms at full speed to the top of the tallest tree, claws that could rip a man’s body like a band saw. Finally, the last grain of salt was gone, and again we sat together. I wondered if this could be for real.

Bosco stood up on all fours, burped a long, fishy belch and stepped out into the rainy blackness. But he soon was back—with a message. He sat down near the sleeping bag and attempted to scratch the area of his rump just above his tail, but he couldn’t reach it. Again and again he nudged me and growled savagely at the itch. Finally I got the message and laid a light hand on his back. He flattened out to occupy the total seven feet of the lean-to as I began to scratch through his dense, oily hair.

Then the full significance of his visit hit me. Just above his stubby tail, several engorged ticks were dangerously embedded in swollen flesh. When I twisted out the first parasite, I thought I was in for a mauling—his roar shook the forest. But I was determined to finish the job. Each time I removed a tick, I showed it to him for a sniff before dropping it on the fire, and by the last one he was affably licking my hand.

A cold, sniffling nose awakened me several times during the night as the bear came and went. He left the sleeping bag wetter and muddier each time he crawled around and over me, but he never put his full weight down when he touched any part of my body.

Becoming brothers

The next day I set off again, over a ridge, down through a chilly river, up to the next crest, through thickets of birch and alder and down a wide, north-running river canyon. To my surprise, Bosco followed like a faithful dog, digging grubs or bulbs when I stopped to rest. That evening, I fished for Bosco’s supper.

As the days passed and I hiked north, I used a system of trout, salt and scratch rewards to teach the bear to respond to the call “Bosco!” One evening, he walked over to the log where I was enjoying my pipe and began to dig at my boots. When I stood up, he led me straight over to a dead hollow bee tree at which he clawed unsuccessfully.

Returning to camp, I covered my head with mosquito netting; tied shirt, pants and glove openings; and got the hatchet. I built a smoke fire near the base of the tree and hacked away until the hollow shell crashed to earth, split wide open and exposed the hive’s total summer production. For my understanding and efforts, I received three stinging welts. Bosco ate 20 pounds of honeycomb, bee bread and hundreds of bees. He snored most of that night at the foot of the sleeping bag.

At campsites, Bosco never tolerated long periods of relaxation and reflection, and true to my sucker form where animals are concerned, I babied his every whim. When he wanted his back scratched, I scratched; when he wanted a fish dinner, I fished; when he wanted to romp and roll with me in the meadow, I romped and rolled—and still wear scars to prove that he played games consummately out of my league.

During one particularly rough session, I tackled his right front leg, bowling him over on his back. As I sat on his belly, he retaliated with a left hook that not only opened a five-centimetre gash down the front of my chin but also spun me across the meadow. When I woke up, Bosco was licking my wound. His shame and remorse were inconsolable. He sat down with his ears back and bawled like a whipped pup once I was able to put my arm around his neck and repeat all the soft ursine vocabulary he had taught me.

It is not my intention to attribute character traits to the bear that he could not possess or exaggerate those he had. I simply studied him for what he was and saw him manifest only the normal qualities of his species, which were formidable enough without exaggeration. Other than calling him Bosco, I never attempted human training upon him. On the contrary; I did everything possible to train myself to become a fellow bear.

The affection Bosco and I developed for each other was spontaneous and genuinely brotherly. When it occurred to him to waddle over my way on his hind legs, grab me in a smothering bear hug and express an overflowing emotion with a face licking, I went along with it for two reasons. First, I was crazy about that varmint. Second, I nourished a healthy respect for what one swat from the ambidextrous giant could accomplish.

A fond farewell

Although his size and strength made Bosco almost invulnerable to attack by other animals, he had his own collection of phobias. Thunder and lightning made him cringe and whine. When whisky jacks flew into camp looking for food, he fled in terror, the cacophonic birds power-diving and pecking him out of sight.

Bosco’s phenomenal sense of smell amazed me. Trudging along behind me, he would suddenly stop, sniff the air and make a beeline for a big, succulent mushroom 200 yards away, or to a flat rock across the river under which chipmunks had warehoused their winter seed supply or to a berry patch two ridges over.

One afternoon when we were crossing a heath where dwarf willows grew in hedge-like clumps, Bosco suddenly reared up and let out a “maw!” I could detect no reason for alarm, but Bosco stood erect and forbade me to move. He advanced, began to snarl—and pandemonium broke out. From every clump of willows sprouted an upright bear! Black bear, brown bear, cinnamon bear and one champagne.

But these were young bears, two-year-olds, and no match for Bosco. He charged his closest contestant with the fury of a Sherman tank, and before the two-year-old could pick himself up, Bosco dispatched a second bear and tore into a thicket to dislodge a third. At the end of the circuit, my gladiator friend remembered me and trudged back, unscathed and still champion.

That night, we sat longer than usual at the campfire. Bosco nudged, pawed, talked at great length and looked me long in the eye before allowing me to retire. In my ignorance, I assumed it was a rehash of that afternoon’s battle. He was gone most of the night.

Along toward next mid-afternoon, I sensed something was wrong. Bosco didn’t forage but clung to my heels. I was looking over a streamside campsite when the big bear about-faced and broke into a headlong, swinging lope up the hill we had just descended. I didn’t call to him as he went over the crest full steam without once looking back.

That evening, I cooked supper with one eye on the hillside, then lay awake for hours waiting for the familiar nudge. By morning, I was desolate: I knew I would never again see big brother Bosco. He left behind a relationship I shall treasure.

If you enjoyed the story of Bosco the bear, don’t miss this incredible true tale of a photographer’s special bond with a Canada lynx.

My three-year-old grandson was admiring his cousins’ new bunk beds. He was about to climb into the lower bunk to try it out when his mom cautioned him about being extra careful not to hit his head.

He said, “I know! That’s why they’re called bonk beds.” —Val Bayer, North Vancouver, B.C.

My two-year-old granddaughter wandered into the kitchen to wash her hands. Her mom, who was busy, told her to use the bathroom sink instead. My granddaughter’s response?

“Mommy is giving me attitude!” —Lyn Thompson, Ilderton, Ont.

When my daughter was seven, she was horrified to learn that her grandparents had real names and were not, in fact, called Jeans (Grandma liked wearing jeans) and Keys (Grandpa always held the keys). —Gloria Myers, Scarborough

My four-year-old granddaughter was pretending to enjoy a piece of make-believe cake.

When her older brother, who is allergic to nuts, asked for his own pretend slice, she quickly responded, “No, you can’t have any. It has nuts in it!” —Jennifer Khan, Vaughan, Ont.

The family dog, Dooley, was about to celebrate his 11th birthday. Our five-year-old grandson suggested that a frisbee might be a good gift, but we pointed out that Dooley was now a senior citizen and too old for one.

“Don’t worry,” our grandson said. “It says, ‘ages five to 12’ right on the box.” —Sally Roper, Etobicoke, Ont.

I asked my five-year-old granddaughter what she wanted to be when she grew up. She replied, “A cashier.”

When I inquired further, she said, “Because I get to take people’s money.” —Gayden Warmald, Victoria, B.C.

My six-year-old grandson, Lucas, and I play a game called mystery cookies, where I bake cookies and he’ll guess some of the ingredients.

Lucas was getting quite good at recognizing ingredients until recently, when I made some extra-chewy cookies and asked him to name what was in them.

He replied: “Sponges?” —Donna Fulcher, Drayton, Ont.

It was difficult to see my two-year-old granddaughter when the pandemic began. But when lockdown restrictions in our area were lifted last May, I visited her with my hand puppets, and we had so much fun.

The next time, I forgot my puppets. I said I missed her and asked if she missed me. “No,” she replied, “I miss the puppets.” —Rena Hadlington, Brampton

When my grandson and I arrived at our vacation cabin, we kept the lights off until we were inside to keep from attracting pesky insects. Still, a few fireflies followed us in.

Noticing them before I did, he whispered, “It’s no use. Now the mosquitoes are coming after us with flashlights.” —Barthelemy Petro, Portland, Ont.

While I was repairing my six-year-old granddaughter’s dresser, I heard the following exchange between her and her friend:

My granddaughter: That’s my grandma. She’s our fix-it-up person. Do you have a grandma?

Her friend: No, I have a nanna.

My granddaughter: Well, you should really get a grandma. —Patricia Power, Oshawa, Ont.

A few nights ago, my eight-year-old granddaughter stayed over at our place. The following morning, she watched me rub anti-wrinkle cream on my face.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “You don’t have to worry about this yet. You aren’t old like me.”

“You’re not old,” she answered. “You’re middle-aged.” —Robin Fronteddu, Burlington, Ont.

During the pandemic, my two granddaughters—six and eight years old—were being home-schooled by their mom. One day, the eight-year-old had a spelling bee with her sister. “Spell ‘elephant,’” the older one said.

“Let her spell small animals, not big ones,” said her mom.

The older sister paused, then said, “Spell ‘mosquito.’” —Misir Doobay, Toronto

My four-year-old grandson loves picking dandelions, placing them in a glass of water and presenting them to his mom. One day, I saw him reach for the glass of dandelion water and stopped him just before he drank from it.

“Don’t drink that,” I said. “That water is yucky.”

He replied, “Well, it tasted good yesterday.” —Tammy McKenzie, High River, Alta.

My husband was reading a story to our three-year-old granddaughter, Kate, when her attention began to wane. He tried a new approach: reading a couple of sentences at a time and then pointing at pictures.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“A giraffe,” Kate answered.

This went on for a while but eventually got old, too.

“What’s that?” he asked, pointing to a zebra.

Exasperated, Kate replied, “Geez, Granddad, don’t you know anything?” —Wellner Gagnier, Delta, B.C.

Before the pandemic, our three-year-old grandson, Matthew, went to Disneyland with his parents. Before they left, Matthew’s grandpa had asked, “Can I come along in your suitcase?”

When they got to their hotel and opened their suitcases, Matthew looked into one of them. Confused, he called out, “Grandpa?” —Gail Rode, West Kelowna, B.C.

Next, check out our round-up of parents revealing the funniest things their kids have said.

How Tom Forrestall Became One of Canada’s Leading Egg Tempera Painters

Tempera is a permanent, quick-drying painting medium that combines colour pigments with a binding agent. Because this agent is often a glutinous material such as egg yolks, tempera is also known as egg tempera. It’s one of the oldest painting mediums, dating back to murals in the ancient dynasties of Egypt, Babylonia and China, among others.

Because tempera dries so quickly, colour-blending is not possible once applied to a surface. That’s why shading is done by short strokes of colour. By contrast, oil takes longer to dry, allowing for more realistic shading. Another difference is that oil is reflective, while tempera is matte.

Nova Scotia-based painter Tom Forrestall has been using this ancient method for almost 70 years and is today recognized as one of the country’s leading realist egg tempera painters. Renowned Canadian artist Alex Colville introduced Tom to the technique in 1956, when Tom was his student.

Tom was born in the Annapolis Valley in 1936. He grew up there—in Middleton—as well as in Dartmouth, and started attending art classes at an early age. In 1954, he began studies in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, having been awarded an entrance scholarship. Along with other soon-to-be-noted artists such as Christopher and Mary (née West) Pratt, Hugh MacKenzie and D.P. Brown, Tom studied under department head Lawren P. Harris (son of Lawren S. Harris of the Group of Seven) and Alex Colville, who taught at Mount Allison from 1946 to 1963.

Following his graduation in 1958, Tom married Natalie LeBlanc, whom he had met at the university. He soon received a Canada Council Grant for independent study, which allowed the couple to travel around Europe, visiting museums and viewing art.

In 1959, Tom became the assistant curator of the newly launched Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton. By the following year, he was commissioned by the Province of New Brunswick to create a painting for Princess Margaret in celebration of her wedding. Encouraged by this early success, he began to devote himself full-time to painting.

However, he was and remains a highly creative painter whose unique style hasn’t always been understood. For one, his quest to escape the constraints of traditional square and rectangular canvasses led him to use round-edged panels and a variety of other shapes, including those derived from the triangle, circle and rhombus. He has often quoted another original thinker, Oscar Wilde, who said, “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.”

Tom’s work has been widely recognized: He has been inducted into the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia, received a Queen’s Jubilee Medal, and earned several honourary doctorates as well as appointments to various academic and art boards. Among his special commissions is a painting for Pierre Trudeau of his sons, a gift from the nation upon the prime minister’s retirement. Tom’s had numerous solo and group exhibitions and, today, his art can be found in galleries and private collections in Canada, the U.S., Europe and the Middle East.

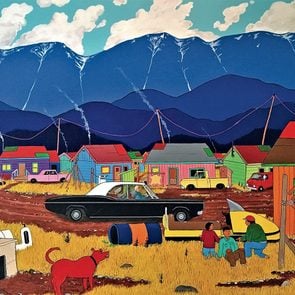

A Car For All Seasons

In 2013, Mercedes-Benz Canada bought Tom’s 1980 300D and commissioned him to depict the four seasons on its surface; the resulting piece is titled “A Car for All Seasons.” Tom credits the motivation and title, as well as the link to the luxury-car company, to his long-time friend Mary O’Regan, whose family owns O’Regan’s Mercedes-Benz in Halifax. To honour her, Tom painted Mary’s name on his mobile canvas. His son Frank got involved, too, capturing the months-long creative process on video:

“If you broke it down, there would be probably about 15 paintings,” says Tom. Of the work’s portrayal of seasonal transformation, he explains, “Winter, from spring down at the bottom, goes into summer.”

Artist Tom Forrestall has authored and appears in several books about and inspired by his craft, including Shaped by This Land (1974); This Good Looking Land: 117 Sketches of Nova Scotia (1976); Returning the Favour: Vision for Vision (1992); and Tom Forrestall: Paintings, Drawings, Writings (2008), by Tom Smart. Tom’s paintings are sold by the Mira Godard Gallery in Toronto.

Next, read the incredible story of one family’s heartwarming relationship with Canadian folk artist, Maud Lewis.

When it comes to the royal family, there is one rule that must never be broken: no matter how close they are in line to the throne, each member of the family must always bow or curtsy to the Queen. But beyond that, there’s surprisingly little royal etiquette for the Windsor clan to follow. In fact, most of the royal family rules you’ve probably heard of—likely reported as scandals in which Kate or Meghan allegedly broke “royal protocol”—are myths, manufactured by the media for the sake of a sensational headline. So let’s get to the truth behind these royal rules that apparently govern everything from their décolleté down to their toenails (literally).

Dark nail polish is frowned upon

Need proof that the British tabloids are hungry for royal gossip? If their headlines are anything to go by, the Duchess of Cambridge has sparked multiple royal scandals with her pedicures. On glam nights out, you will often spot Catherine with burgundy polish peeking out from her Jimmy Choos. While the Queen prefers to sport a pale shade of pink on her nails (Essie’s Ballet Slippers, if you’re wondering), Kate is not breaking any rules (or creating friction with Her Majesty) by opting for dark polish. “There is no actual protocol about dark nail polish,” says royal commentator Omid Scobie in Harper’s Bazaar.

Off-the-shoulder dresses are a no-no

Many of Princess Diana’s dresses made magazine covers back in the day, but there’s one in particular that achieved legendary status. In June 1994, on the same night Prince Charles’s tell-all interview confirming his affair with Camilla aired, Diana arrived at London’s Serpentine Gallery in what was hailed as “the Revenge Dress.” But did she actually flout protocol by wearing an off-she-shoulder number that showed a hint of cleavage? No way, says royal commentator Victoria Arbiter. “There are no set rules, other than being dressed appropriately for the occasion,” Arbiter explains, noting that when Meghan set the world aflutter by wearing an off-the-shoulder outfit to Trooping the Colour in 2018 (above), it was similarly a non-issue.

You must never close your own car door

A royal life comes with a lot of help, but sometimes you have to take things into your own hands, like Meghan did in September 2018, when she—gasp!—closed her own car door. Normally, a protection officer does this for the royals, but Meghan performed the simple act herself, causing the internet to combust in peak outrage at this perceived breach of protocol. In response, Arbiter tweeted:

Current state: Poking my own eyes out after reading Meghan “broke protocol” by shutting her car door. Car door shutting does not fall under protocol!

— Victoria Arbiter (@victoriaarbiter) September 25, 2018

Royals, they’re just like us—even when it comes to getting in and out of cars.

Never wear wedges in the Queen’s presence

The day after Kate got married, she left Buckingham Palace in a pair of wedge heels, to the alleged horror of the Queen. See, there’s rumoured to be an unspoken rule in the royal family that no one wears wedges around Her Majesty because she detests the style. Kate herself proved this to be false, however unwittingly. In 2019, while showing the Queen the garden she designed for the RHS Chelsea Garden Show, the Duchess wore a pair of her beloved wedges. By all accounts, Her Majesty was far more interested in the blooms than any bit of fashion Catherine was wearing. Long live the wedge!

Pantyhose are a necessity

When Meghan arrived at her engagement photocall with Prince Harry back on November 27, 2017, there was one accessory missing—pantyhose. Cue the media slating Meghan for disregarding royal protocol. “There are no rules for royal women regarding pantyhose,” notes royal expert Marlene Koenig in Harper’s Bazaar. “It is not required by any decree from the Queen.” The Duchess of Sussex tends to wear pantyhose around the Queen as a sign of respect, but otherwise she rocks bare legs.

Physical contact is to be limited

How does one interact with a member of the royal family? Well, there is supposedly a rule that you should never touch a royal, say with a handshake or hug, unless they initiate it. Except in 2009, when the Queen posed for photos with Barack and Michelle Obama, the First Lady snuck an arm around Her Majesty—and the Queen reciprocated! Did the Queen disobey her own rule? Her senior dresser (and close friend), Angela Kelly, says absolutely not. “It was a natural instinct for the Queen to show affection and respect for another great woman and really there is no protocol that must be adhered to,” Kelly explains in her book, The Other Side of the Coin: The Queen, The Dresser and The Wardrobe. In fact, you’ll notice William, Kate, Harry and Meghan are an affectionate bunch, freely reciprocating hugs from well-wishers. So if you meet a royal, go in for that hug!

Next, find out 40 little-known facts about Prince Charles and Princess Diana’s wedding.