10 Incredible Canadian Women You Didn’t Learn About in History Class

To celebrate International Women's Day on March 8, we're taking a look at the remarkable women who helped shape Canada—and continue to influence and inspire us today.

Inspiring Women in Canadian History

Marie-Josèphe Angélique (1710-1734)

In 1725, a French merchant forced Marie-Josèphe Angélique, a Portugal-born Black woman, to work in Montreal as a domestic slave. When 29-year-old Angélique overheard the merchant’s widow planning to sell her to another slave owner after nine years of having her demands for freedom denied, she fled the house where she was being kept, reportedly setting fire to her bed. That same evening, the south of rue St-Paul caught on fire, spreading rapidly, thanks to strong winds. In less than three hours, 46 homes and buildings burned down, but no one died. The resulting trial lasted six weeks, during which Angélique adamantly denied all accusations from the 22 people who testified against her. On June 4, 1734, a judge found Angélique guilty and sentenced her to death. Whether or not Angélique truly caused the fire, her trial and death symbolize Canada’s part in the slave trade. Today, Angélique is remembered as the first Black person in North America to challenge her slave status.

Shawnadithit (c.1800–1829)

Shawnadithit was the last member of the Beothuk, Algonquian peoples who lived in the south and northeast coasts of Newfoundland and numbered approximately 500 to 1,000 members when they first came into contact with Europeans in the 1500s. By the 1800s, when Shawnadithit was a few years old, that number was far less. European colonizers from England and France had settled for over a century, bringing disease and sowing conflict. While living with a group of Europeans who captured her, Shawnadithit would go on to witness the decline and eventual extinction of her people. In 1828, when she was in her mid to late 20s, the Beothuk Institution in St. John’s commissioned Shawnadithit to document the languages and customs of her people. She did so through telling stories and sketching maps, tools and people. Her documentation work is responsible for most of what we know of Beothuk culture today.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823–1893)

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was the first Black woman newspaper editor and publisher in North America. In 1853, she founded the Provincial Freeman, a weekly newspaper published in Toronto, Windsor and Chatham that advocated for equality and literacy for Black people in Canada and the United States. She also wrote about Black people thriving in freedom to promote emigration to Canada. In 1851, she established a racially-integrated school for Black refugees in Windsor. After moving back to the U.S. in 1861 after 10 years in Canada, she became one of the first Black women to earn a law degree in the U.S. In 1994, the Government of Canada named Shadd a Person of National Historic Significance, recognizing her publishing accomplishments and her community work.

Here are 10 historical landmarks every Canadian should visit.

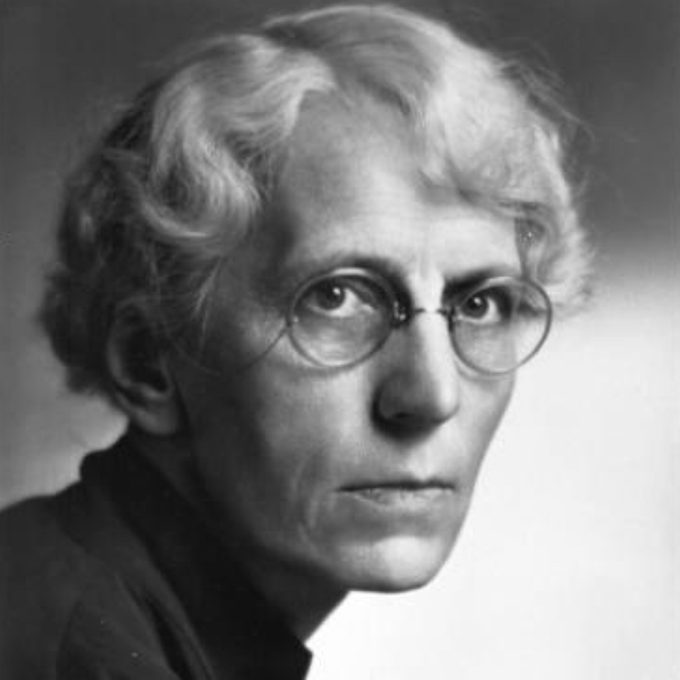

Ella Cora Hind (1861–1942)

Ella Cora Hind was the first woman journalist in Western Canada. After being denied a reporter position at the Manitoba Free Press in 1882 for being a woman, she became a public stenographer and kept a close eye on prairie farming developments. Despite being denied a full-time position, she frequently submitted articles on farming to the Free Press, and her farm upbringing made it easy for her to speak with agricultural workers. Soon, she became popular for her grain expertise. Her opinion was valued so much that it would often influence Winnipeg Grain Exchange prices. Finally, she was hired as Manitoba Free Press’ agricultural editor, and also founded the Canadian Women’s Press Club’s Winnipeg branch in the mid-1900s. She fought for women’s rights and helped lead the suffragist movement that witnessed Manitoba grant women the right to vote and hold office. Hind received an honourary LL.D from the University of Manitoba in 1935.

Alice Wilson (1881–1964)

In 1909, Alice Wilson became the first woman geologist in Canada, and in 1938, she became the first woman Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, a council of distinguished scientists, artists and scholars. At age 28, she worked as a museum assistant for the Geological Survey of Canada cataloguing and labelling collections at the Victoria Memorial Museum. However, the survey banned her from conducting field studies in remote locations with male colleagues—a policy that didn’t change until 1970—so she made shorter solo trips to the Ottawa-St. Lawrence Valley, studying fossils and rocks on foot and by bicycle. She later bought her own car when the survey denied her one—even though it was common practice for male colleagues. When Wilson retired in 1946, the survey had to hire five new people to do the work she did alone. She received an honourary degree from Carleton University in 1960, where she had lectured on paleontology from 1948-1958.

Here are the best places to see dinosaur fossils across Canada.

Elsie MacGill (1905–1980)

In the early 1920s, Elsie MacGill was the first Canadian woman to earn a degree in electrical engineering, the first woman in North America to earn a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, and the first Canadian woman to become a practicing engineer. During the Second World War, she designed the Maple Leaf II Trainer: one of the first aircraft to be designed by a woman, it was a biplane trainer that MacGill re-engineered to be faster than its predecessor. After the war, she worked in aeronautical consulting and was a women’s rights activist. She held leadership roles at the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs from 1956 to 1964. Three years later, she worked at the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, where she successfully fought for their 167 recommendations to be implemented by the federal government.

Read the incredible story of Canada’s first commercial flight.

Jean Lumb (1919–2002)

Jean Lumb played a pivotal role in reforming Canada’s discriminatory immigration laws. In 1959, at age 40, she opened her first Cantonese eatery in Toronto, where she would host discussions on discriminatory legislation with both politicians and activists. Those gathered would discuss older legislation, such as the Chinese head tax, which was enacted to discourage immigration and charged $50-$500 per family member to enter Canada, and the more recent, but equally-prejudiced, Chinese Immigration Act, which rendered the head tax moot by denying entry to most Chinese immigration applicants. The latter was repealed in 1947, but remaining restrictions made it nearly impossible for Chinese immigrant families to reunite in Canada. That changed in 1957 when Lumb and 39 others—all men—formed a delegation to successfully abolish all immigration restrictions based on race, and instead establish criteria based on skills and education. Lumb was also the first Chinese-Canadian woman to be inducted into the Order of Canada.

Can you name these famous Canadian heroes?

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013)

As one of Canada’s most acclaimed graphic artists, Kenojuak Ashevak travelled the world to showcase her Inuit art throughout the 1980s and early 2000s. In the 1950s, she became the first woman to collaborate with West Baffin Co-operative, a well-known printmaking shop at Cape Dorset focused on Inuit graphic art. Following her debut there, Ashevak received near-instant recognition for her simple yet whimsical interpretations of the natural world. Her most famous work, The Enchanted Owl, which uses energetic linework, was featured on a Canada Post stamp in 1970. In 1993, Ashevak was commissioned to create a piece she called Nunavut – Our Land to commemorate the many milestones leading to the establishment of the territory. It’s a lithograph depicting Arctic life in Canada and is on display in the Canadian Museum of History. She was a Companion in the Order of Canada and is the first Inuit artist inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame.

Here are more mind-blowing artefacts you’ll find in Canadian museums.

Dr. Lillian Dyck (1945–Present)

In 1981, Dr. Lillian Dyck became one of the first Indigenous women in Canada to receive a doctorate in the sciences. Dyck went on to work as a neuropsychiatry professor at the University of Saskatchewan from 1981-2005, eventually becoming an associate dean. Dyck is also the first Indigenous and Chinese-Canadian woman appointed to the federal Senate. She retired in 2020 after years of advocating for the rights of Indigenous peoples, Chinese-Canadians, and women. She was a leader in the fight for the 2015 inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, challenging the RCMP’s questionable statistics and pushing for harsher sentences for people who harm Indigenous women. In 2019, she received the YWCA Women of Distinction Lifetime Achievement Award both for her leadership in the sciences and for serving as a role model within Indigenous communities.

These podcasts for women are worth adding to your playlist.

Shirley Firth (1953–2013) and Sharon Firth (1953–Present)

Twins Shirley and Sharon Firth were among the first Indigenous athletes to represent Canada at the Olympics. They were members of the first Canadian women’s cross-country ski team and competed in four Winter Olympic Games from 1972-1984. Between the two, they won 79 medals at the national championships. After retiring from skiing, Sharon returned to the Northwest Territories in the mid-’80s and re-established the defunct Territorial Experimental Ski Training Program, the same Indigenous youth-targeted initiative that introduced her and Shirley to competitive skiing. Shirley moved to Paris, where she taught about Dene and Inuit cultures in numerous European institutions. In 2015, they were inducted into the Canada Sports Hall of Fame.

Next, read the incredible stories of 20 more unsung Canadian heroes.