This 10-Year-Old Got Impaled By A Skewer. Could Doctors Remove It In Time?

Xavier Cunningham fell onto a rotisserie skewer and impaled his face. Doctors couldn’t believe he was still alive.

The fall

Xavier Cunningham was having fun that warm Saturday afternoon in September 2018 with his buddies Silas and Gavon. Xavier, a bubbly, energetic 10-year-old, enjoyed playing in the yard behind his house in Harrisonville, Missouri.

That day, the trio was chucking around a stainless-steel skewer, throwing it into the ground like a spear. At 43 centimetres long and more than half a centimetre thick, the square-edged skewer was used to rotisserie meat; one end had four sharp prongs attached.

Eventually, they ditched the skewer near a neighbour’s tree house, sticking it in the ground with the four prongs anchoring it. With the neighbour’s permission, they climbed the three-metre ladder. Up top, a few yellow-jacket wasps buzzed around. “If we don’t bother them, they won’t bother us,” said Xavier.

But the boys hadn’t seen the large wasp nest wrapped around part of the tree house. Soon the insects were coming at the panicked boys thick and fast, in a dense black cloud. “I’ll get my mom!” Xavier yelled, but now he stared, frightened, at the tree-house ladder, which was covered in a seething mass of angry wasps. This is going to hurt, he thought. His hands crunched on the insects and the stings were painful as he grasped each rung, going as carefully and quickly as he could.

When he was about halfway down, a wasp painfully stung the thin skin of a knuckle on his left hand. As he swatted at it with his right, he lost his balance and fell, face down. Just before breaking his fall with his arms, he felt a sting just under his left eye. Was that a wasp? he thought. Then he realized he’d landed on the metal skewer. Nearly half of it was buried in his head. Screaming, he got up and ran toward home.

Gabrielle Miller, Xavier’s 39-year-old mom, was upstairs folding laundry in the two-storey brick home she shared with her husband, Shannon, a high school teacher, and their four children. Shannon had taken two of their kids on a day trip to nearby Peculiar, while Gabrielle, who manages a local title-insurance business, stayed at home with Xavier and his 14-year-old sister, Chayah. She heard her son screaming and sighed. When will he grow out of this stuff?

Xavier usually made a fuss over the smallest scratch. If one of their two dogs jumped up on him, he’d start screaming; he was too scared to walk Max, the coonhound he’d gotten as a puppy, because the dog pulled on the leash. His overreactions were pretty much a daily occurrence.

Gabrielle was almost down the stairs, Chayah right behind her, when Xavier pushed the front door open, shrieking, “Mom, Mom!” Gabrielle was trying to make sense of what she was seeing. “Get them off!” Xavier was yelling, batting at wasps. She pulled wasps off him, getting stung herself.

Gabrielle was confused and shocked. “Who shot you?!” It looked like there was an arrow through her son’s face; a single trickle of blood ran down from it. With his stung, swollen hands, he touched the tip of the skewer on the back of his neck, a lump that hadn’t pierced the skin.

Gabrielle guided Xavier out the front door and into the front of her Camaro. She then ran to the driver’s side. A shocked neighbour, watching as the car backed out into the road, thought, That boy’s not coming home.

Hospital

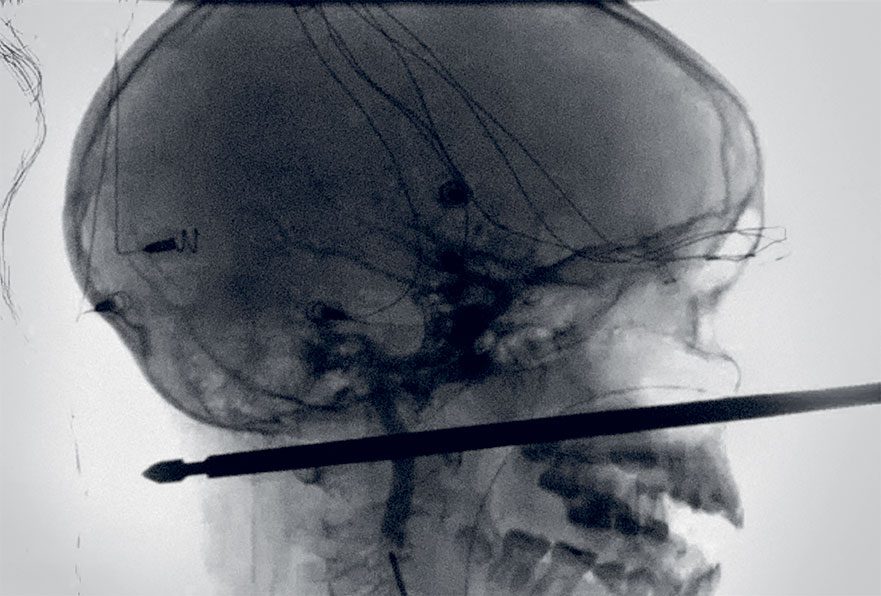

Gabrielle rushed into the Cass Regional Medical Center emergency room with a remarkably calm Xavier walking alongside her, the huge spike sticking more than 20 centimetres out of his face. The skewer didn’t appear to have hit his spine, but an X-ray can’t show tissue damage. ER staff realized they’d have to send him somewhere with more advanced imaging equipment: Children’s Mercy Hospital in downtown Kansas City, 40 minutes north.

To prevent Xavier from moving his head, staff fitted a plastic cervical collar around his neck and wrapped his entire head in white gauze to help stabilize the skewer. The only thing left exposed besides it and its four sharp prongs—caked with mud from where they’d been stuck in the ground—was his mouth.

Dr. Jeong Hyun, the pediatric surgeon working the emergency room at Children’s Mercy that afternoon, couldn’t believe his eyes when Xavier was rolled in at about 4 p.m. He asked Xavier to wiggle his toes and fingers. He was relieved that Xavier was so responsive; it meant that neither his spine nor brain had likely been hit.

The skewer also hadn’t punctured any of Xavier’s vital blood vessels. If an artery such as the carotid or the vertebral, which carry blood to the brain, had been hit and was leaking out internally, it could cause a stroke. Dr. Hyun was amazed to see via a CT angiogram that nothing was leaking and the skewer had narrowly missed every vital artery. They looked to be millimetres, if that, away. That’s spectacular, thought Dr. Hyun. But now what?

If the skewer had any kind of bend, a sharp edge or a gap, then pulling it out would be rolling the dice, as it could catch on an artery and rip it open. But the only way to get a clear picture of the skewer was with biplane angiography—a piece of equipment that gives doctors a three-dimensional view inside the vascular system. Children’s Mercy did not have it, since vascular problems are so rare in kids. But the University of Kansas Medical Center, less than five kilometres away, did. Xavier would need to be transported to a third hospital.

It was now 7:30 p.m. Xavier had been impaled for six hours.

Preparing for surgery

Dr. Koji Ebersole, an endovascular neurosurgeon at the University of Kansas Medical Center, stared at a photo of Xavier on a gurney. He had also never seen anything like the boy’s injury. How deep is that thing? he wondered. And how is this kid even alive?

Dr. Ebersole had to get Xavier into the angiography suite as soon as possible —but first he needed a plan. He was the best-trained neurosurgeon for more than 200 kilometres, but there was nothing in the medical textbooks that could help with this one. He needed to make some phone calls.

Meanwhile, his colleague at KU Hospital, Dr. Kiran Kakarala, an otolaryngologist (or ENT—ear, nose and throat specialist), was at home with his family when he received Xavier’s X-rays. His first thought was that the odds were against the boy. How can someone live through an impalement like that? he thought.

Yet he was alive—which told Dr. Kakarala they had a chance of removing it. But how? If they hit any key blood vessels, Xavier could experience a debilitating stroke, or he could die.

For the next couple of hours, Drs. Ebersole and Kakarala consulted with various specialists. They knew they needed to see exactly what the skewer had damaged, or still could damage, and then remove it while carefully monitoring its exit. Using the angiography suite required a team of 15 to 20 medical staff. It would be tough to get the right people together so late on a Saturday evening. Plus they’d have a better chance of saving the boy if they were well rested.

But could Xavier wait until morning? Was he stable mentally? Dr. Ebersole asked the doctors in pediatric ICU, where Xavier and his family waited, to gauge whether he was brave enough to hold on; everything depended on his state of mind and his ability to refrain from grabbing the skewer. When Dr. Ebersole heard back from the hospital at about 11:30, he made his final call of the evening. “We can wait until morning,” he told a relieved Dr. Kakarala. “The boy is on board.”

It took both doctors longer than usual to get to sleep; each tossed and turned as they ran through various scenarios. It could go either way.

“The biggest problem is that barbed end,” Dr. Ebersole told the team assembled at 8:30 a.m. in the angiography suite. He pointed to a computer screen; the image on it was an X-ray, which showed the skewer had a notch in the shaft near the point. If they pulled the skewer out the way it went in, the notched tip could rip an artery open, but it was also their safest option.

One floor below, Dr. Kakarala was with the anaesthetists, inserting a breathing tube into Xavier so he could be anaesthetized. The skewer had gone through his jaw muscles, and Xavier couldn’t open his mouth widely enough to fit a tube, so the doctors would thread it through his nasal passage and down his throat. This is painful for adults and worse for a child. “I’m sorry, but this is going to hurt,” Dr. Kakarala explained gently.

They numbed his nasal passages and started the procedure. Xavier didn’t complain, even when they struggled to get it around the sharp corner at the top of the nasal passage. It took about 40 minutes. Finally, Xavier could be put under—and they’d get a look inside his head.

One lucky kid

In the angiography suite, about 20 surgeons, specialists and nurses waited. The boy was transferred to the operating table and about a dozen little wires with fine needles were pierced into Xavier’s scalp; they would continuously monitor the brain’s electrical activity. If there was any decrease, the technologist stationed in the corner of the room would alert the surgeons.

Two mechanical arms, one attached to the floor and the other to the ceiling, were positioned close to Xavier’s head. Each arm held two X-ray devices that moved in wide arcs around his head to create 3-D images that appeared in real time on a large flat-panel display.

Drs. Ebersole and Kakarala could now see the one-in-a-million trajectory the skewer had taken: it had missed Xavier’s spine by less than two centimetres. It had missed the cerebellum, located at the bottom of the brain, which controls functions like balance and speech—also by less than two centimetres. It had punctured the carotid sheath, which contained his hypoglossal and vagus nerves, which control tongue function, swallow reflex and the voice box, but didn’t appear to have damaged them.

The skewer had torn the jugular, but it appeared to have occluded, or sealed itself, against the skewer. Most importantly, it missed both the carotid and vertebral arteries. In fact, it appeared to have nudged them out of the way—without puncturing them. I don’t know how a kid can be so lucky, thought Dr. Ebersole.

It’s time

The team was as ready as they’d ever be. Now they had a view of things from inside and outside. Though nobody had discussed up to that point who was actually going to attempt to pull out the skewer—there was no rule book for this situation—Dr. Jeremy Peterson, a 32-year-old chief resident, thought it might fall to him, as he was training under Dr. Ebersole.

To get a feel for the skewer, Dr. Peterson placed his left hand at its base as an anchor, while his right hand grasped just above his left hand. He nudged it back and forth ever so slightly while Dr. Ebersole watched on the screen in case the movement harmed a vessel; the skewer barely moved. “It feels pretty solid,” Dr. Peterson said.

“Okay, let’s go,” said Dr. Ebersole. He’d be the eyes, watching the monitor, while Dr. Peterson would work on getting it out. He’d have to do it slowly and smoothly while being careful that his left hand didn’t exert too much pressure because it was literally on Xavier’s eye.

Dr. Kakarala had one hand on Xavier’s face to help steady his head. Dr. Peterson squeezed with his right hand while simultaneously pulling up with the same hand. The skewer was surprisingly hard to budge. It took all the strength in Dr. Peterson’s right arm. Then it did move about a couple of centimetres—and stopped. “It feels stuck on something,” said Dr. Peterson.

The screens showed that it was now so close to the vertebral artery that it was bending it.

They tried a new angle to move the skewer away from the artery. Looks like it’ll clear that now, Dr. Ebersole thought. “Okay, go again,” he told Dr. Peterson. It worked. Dr. Ebersole watched the tip of the skewer safely pass the vertebral artery.

“It’s sliding pretty easy now,” said Dr. Peterson. Yet he continued to pull it very slowly, especially as it passed the jugular.

Then, finally, the last hurdle: the carotid artery. The rod passed it smoothly, too—and suddenly, it was out. Dr. Peterson quickly put his finger in the hole, in case blood started gushing out. It didn’t.

Success

A cheer went up from many in the room—but not from Drs. Kakarala, Ebersole or Peterson. They wouldn’t relax until Xavier was conscious and they could know he was definitely unscathed. While it appeared the boy was out of danger, it was now a matter of waiting and seeing how he recovered.

It was 3 p.m. when Dr. Ebersole entered the waiting room and told Xavier’s parents simply: “It’s out. He’s okay.” It was the happiest moment of Gabrielle’s and Shannon’s lives.

“Can I hug you?” Gabrielle asked Dr. Ebersole, and she did.

When Xavier came out of the anaesthesia a short time later, a Spider-Man Band-Aid covering the wound on his face and with stitches along his neck, he asked, “Is it out?” Yes, it’s out, his parents told him. His eyes filled with tears as he looked out the window. “That sunshine, it’s so beautiful,” he said.

Two months after the accident, the only evidence of the skewer was a tiny bump beside Xavier’s nose and some numbness on the left side of his face—miraculously, he had no other permanent damage. His healing had been smooth and uneventful. For a while, his doctor recommended he see a therapist, primarily in case of PTSD.

Aside for a new fear of wasps, Xavier has coped remarkably well. These days, he often grabs the leash to take Max out—he’s no longer scared to walk the dog alone. And when he gets a scrape, instead of going straight to 10 on the pain scale, like he used to, he’ll calmly say, “This hurts pretty bad.”

“Is it skewer bad?” Gabrielle will ask, and Xavier will laugh—crisis over.

He’s still friends with Gavon and Silas, who were rescued from the wasps by members of the fire department who aimed hoses at the swarm. Gavon ended up with 150 stings, while Silas had just one, on his arm—and that entire arm swelled from an allergy he hadn’t known about. He, too, was lucky to be alive.

Next: A snakebite turned this woman’s Thailand vacation into a fight for her life