A Brutal Alligator Attack Was Just the Beginning of His Three-Day Ordeal

Critically injured, and repeatedly stalked by the gator, could Eric Merda navigate his way out of the treacherous Florida swampland?

The stars burn brilliant over Florida’s Lake Manatee as the man backstrokes through the dark water. He’s exhausted and frustrated by his lack of progress but believes he can swim all night if he must. Then a bristling intuition creeps upon him and he sits up in the water and peers to his left. Less than one metre away lurks the unmistakable shape of an alligator’s snout, the slitted eye yellow in the starlight. The man turns onto his stomach and flings out his hands to swim, but the gator strikes, seizing his right forearm in its teeth. The predator twists its powerful body, snapping the man’s arm back at the elbow. For a moment the man’s world goes black. Then, still firmly holding its prey, the reptile dives, looking to drown its victim in the silent midnight depths of the lake. For most of us, surviving a brutal alligator attack would be cause for surrender, but for him, the journey was just beginning.

The way Eric Merda saw it, the past two weeks had been one long, crazy battle with God. The 43-year-old father of seven had always had his struggles—addiction, street fights, run-ins with the law—but things had recently become clear. For one, he’d come to accept that his relationship with the mother of five of his children was over. For another, he’d begun to realize he was running with a dangerous crowd. Intelligent, creative and spiritual, a self-described weirdo, Merda knew he’d been on the wrong track. God was telling him to clean up his act and live up to his gifts.

So he’d been on a sort of ascetic quest. By day, he’d toil beneath the Florida sun in and around his home base of Bradenton, installing and repairing sprinkler systems as he’d done for 25 years. By evening, he’d wander and explore. For the first time, he had no woman or children to come home to.

He spent much of his surplus time on Siesta Key Beach, where he gave himself daring challenges: How far out into the ocean can I go at night? How long can I float faceup with my head tipped back so far that my eyes stay in the saltwater? For a while now, there had been a thin line between embracing life and courting death. Which was it going to be?

Sometimes he slept unsheltered on the sand of Siesta Key. One morning he awoke to see litter scattered along the beach, and felt God telling him that he should clean it up. He began collecting trash. It felt good, so he made a habit of picking up litter wherever he saw it, not just on the beach.

On Monday, July 18, 2022, he had a job up in the rural portions of Manatee County. He was finished by late afternoon. Time to explore. Near an intersection of two country byways, he spotted a dirt road with a sign that read Lake Manatee Fish Camp.

He nosed his old white work van down into the area, past a little country store and some folks pitching horseshoes, and followed the road. It ended at a boat ramp onto Lake Manatee, a man-made reservoir covering about five square kilometres, ringed by wild swampland. Trash lay strewn along the roadside. Merda jumped out of his van, leaving his phone and keys inside, and started collecting the garbage into piles.

After a while, a thought occurred to him: I’ve been working all day. Nobody’s forcing me to pick up trash. I’m going to see what’s in these woods.

With the abandon of a schoolboy, he ran off into the trees. Before long, he encountered a thicket of brush, thorns and vines. Seemingly impenetrable, it presented a nice challenge. He charged into it and did battle for many long minutes. It was exhausting, but he pushed on. When at last he emerged into a grove of scrawny orange trees, he was sweaty, cut up and tired. He had no idea where he was in relation to the lake. He’d been pushing through the thicket for hours, and all he wanted was to get back to his van and go home.

Now Merda spent another couple of hours wandering among the orange trees, which were laid out in an endless grid. No sign of civilization. The lake and his van certainly weren’t out here in an orange grove, so he re-entered the woods and soon found himself mucking around in swamp water. There seemed no way out of this bog.

He laboured for hours as the sun sank. Tall, thick grasses and thorns clogged his way; mud and water filled his boots. His feet hurt so badly that he took his boots off and carried them—but the twigs and brambles lacerated his soles, so he stopped and pulled the boots back on. He tried to navigate by the sun but kept losing it. Each time he picked out a landmark or chose a beeline course, he became hopelessly lost again after just a few minutes.

Darkness was falling when at last he re-emerged onto the shore of the lake.

There across the water stood the boat ramp, now empty, and a little highway bridge, roughly 400 metres away. He was beaten, sore and thirsty. Re-enter the swamp? Out of the question. Who knew where he’d end up? He’d have to swim for it across the lake.

The water was surprisingly cold, especially as it deepened. Merda started out paddling strongly for the opposite bank, drinking lake water to quench his awful thirst. After a few minutes he realized he’d never make it with his clothes on. He shed every stitch, letting his work duds sink to the bottom of the dark lake.

He swam on, but some strange current prevented his progress. He was a good swimmer, yet he somehow kept diverging from his goal. He’d point himself at the boat ramp, swim a few strokes, lift his head and find that he was way off course. It was maddening, but he refused to surrender to emotion. In a fistfight, the guy who comes into it panicking, with no self-control, is the one who gets beaten. The sun disappeared and the stars came out, and still he struggled, alternating between a backstroke and a crawl.

And that’s when he saw the alligator. Before he could swim a stroke, before he could save himself, before he could let out a scream, the creature struck like a snake. It sank its teeth into Merda’s forearm, breaking it at the elbow, and dragged him underwater.

Merda went into fight mode. He swung his other arm around the gator’s middle, clutching at its heaving belly as he kicked his feet to keep from going to the bottom. Man and beast resurfaced and Merda gulped air—but just as quickly the gator yanked him under again. The third time, the alligator did what alligators do: It barrel-rolled its entire body in a vicious coup de grâce, and Merda felt the flesh of his arm tearing away as the limb was severed. The creature disappeared into the darkness, carrying Merda’s forearm with it.

No pain yet, only terror. His one thought was to get out of the water. He swam furiously, paddling with the stump, and came to rest at the lake’s edge not far from where he had entered. Miraculously, the wound was barely bleeding; the gator seemed to have twisted his flesh into its own tourniquet. He paused for a time in the partially submerged grasses, heaving, then spotted a huge tree on drier ground. He dragged himself to it—and screamed for help across the desolate lake.

Then he realized, I’m the only one who can get myself out of this. Just like I’m the only one who can fix every other part of my life. He positioned himself up against the trunk of the tree and waited for dawn. When the pain arrived, it was exquisite.

In the morning, Merda spotted two airplanes. Each time, he climbed up the tree and waved and hollered, which did him no good. He was stark naked in the wilderness, bereft of his right forearm and with nothing to use for a signal. Again, he started pushing through the tall grasses and immediately became lost anew, wandering in circles. He decided the best course was to re-enter the water and wade the lake’s edge, following its curve until it reached the boat ramp.

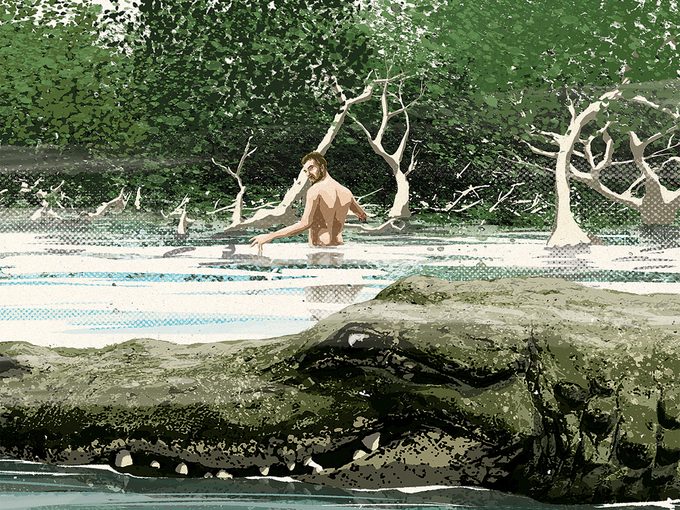

But that proved nearly impossible too. Submerged logs, tall grasses, overhanging brush and sudden drop-offs stymied his progress. He howled in pain when he blundered into a stick that poked into the exposed muscle of his right arm. Chest-deep in the murky water, he looked behind him, and there, roughly 30 metres away, stared the bumpy eyes of the alligator silently following him. He moved to shallower water and the gator eyes sank beneath the surface. All through the long day, as he struggled along, the creature dogged him. Maddeningly, thanks to the meandering shoreline, the boat ramp appeared farther away than ever.

As night fell again, he happened upon a concrete structure at the lake’s edge, no doubt part of the reservoir system. Hungry, thirsty and in agony, he haltingly climbed onto it, stretched out and slept. He awoke in darkness with the horrifying awareness that he was dangerously close to the swamp water, his left arm dangling off the structure like a second proffered morsel. That was enough. He wanted to get out of the swamp. He wanted dry land.

Up until then, Merda had been ambivalent about life and death. Now he could hear God telling him, “All right. After this, I don’t want to hear any more. If you choose to die, you choose to die. If you choose to live, then good luck to you, because it isn’t going to be easy.”

He’d always figured his concept of God would get him kicked out of most churches: By his philosophy, since we’re all made in God’s image, God is part of each of us, and each of us is part of God. Thus, to have faith in God is to have faith in oneself, and to quarrel with God is to quarrel with oneself. And he was done quarreling with himself. In the dark, he blundered his way through what seemed to be an endless stretch of three-metre-tall grasses, the roots of which lay beneath knee-deep water. He was disoriented yet again. The sun dawned on a new day, Merda’s third out here, and before long the Florida heat set the swampland to-broiling. Green horse flies swarmed his injury where the naked muscle twitched have faith in God is to have faith in oneself, and to quarrel with God is to quarrel with oneself. And he was done quarreling with himself.

In the dark, he blundered his way through what seemed to be an endless stretch of three-metre-tall grasses, the roots of which lay beneath knee-deep water. He was disoriented yet again.

The sun dawned on a new day, Merda’s third out here, and before long the Florida heat set the swampland to broiling. Green horse flies swarmed his injury where the naked muscle twitched and the bare bone gleamed. The land was so soggy that even when he wasn’t standing in water, he could scoop at the earth with his good hand and a little puddle of filthy drinking water would fill the depression he’d made. He nibbled at some tiny purple flowers growing throughout the swamplands. He began to fade, utterly spent and bloodied. But he’d made his decision. He’d chosen life, even if it meant the pain and frustration of endless struggle. Whenever his fatigue overwhelmed him, he flattened the tall grasses to make a mat on which to sleep.

His quest was dry land, and at last he found it—only to discover it overwhelmingly choked with thorny vines. It was either the swamp or this endless wall of thorns—no getting around it, over it or under it. He must push through. It’s just a little pain, he told himself. You aren’t even going to remember it once it’s gone. So he dragged himself into the bramble, crab-walking at times, sliced and punctured, pausing periodically to psych himself up for more pain.

In late afternoon, Merda came across a brown beer bottle lying in the mud like a signal from civilization. He knew now that he was saved. How far can somebody throw a beer bottle—10 metres? That meant it must be only that far to the road. You can go another 10 metres, he told himself.

He did, and when he exited the thorns he was staggering alongside the road near the turnaround spot for the boat ramp. On the other side of a wire fence, a man stood beside a red car.

“Hey! Hey!” Merda yelled. The man stared in disbelief at the stranger, naked save for the blood and mud that covered his body. “What are you doing back there?” he said.

“A gator got me!” Merda answered, waving his stump. “You got any water?”

“Holy … ! I don’t have any water, but I’ll get you some, for sure.”

The fence was the final obstacle between him and civilization. Merda had had enough. He lay down in the weeds on the swamp side of the divider and waited for the emergency workers, who would cut the fence and carry him over to the helicopter that would whisk him away to the rest of his life.

Merda spent nearly three weeks in a Sarasota hospital. His wound had become infected in the swamp, so surgeons removed considerably more than the alligator had taken, leaving him with only about half of his upper arm. It’s incredible that he didn’t bleed to death—a miracle, Merda says.

He ate like a machine in the hospital, and sent a buddy out for one meal not on the kitchen’s menu: crunchy fried alligator nuggets.

On his release, he tried to return to work. “I can still do it,” he says, “but with one hand it’s slow.” It wasn’t practical to take up his old trade. So now he’s casting about for some way to make a living while sharing the things he’s learned. Consult? Teach? Write a children’s book? Take up public speaking? Become a comedian?

He says he wants to inspire people to think, “If a skinny dude from Sarasota can fight a gator and survive, why am I afraid to open my own business, go to college or get a contractor’s license?”

The road ahead won’t be easy. Then again, that was part of the deal with God. Sometimes he feels at a loss, as if his dreams sound too ambitious, too ridiculous. But, says Merda with the wisdom of a man who has done battle with the divine, “It sounded pretty ridiculous that I was going to make it out of that swamp alive, too.”

Read on for more Drama in Real Life.