The power of the ocean

My wife, Kay, looked quite miserable standing there as I said goodbye at 6:30 a.m. that Sunday morning in December 1963. She was expecting our first child, and the doctor had firmly told her not to go. Kay was experiencing complications, and travelling would have made her pregnancy riskier. I wish now that the doctor’s advice had applied to me, as well.

Two hours later, however, I was standing on the cliff at Aldinga Beach, 55 kilometres south of our home in Adelaide, South Australia. This was why I’d set out so early. Now I had time to carefully study the dark patterns of bottom growth on the reef under the coming blue-green swells. Aldinga reef is a paradise, a happy hunting ground for underwater spear fishermen like me.

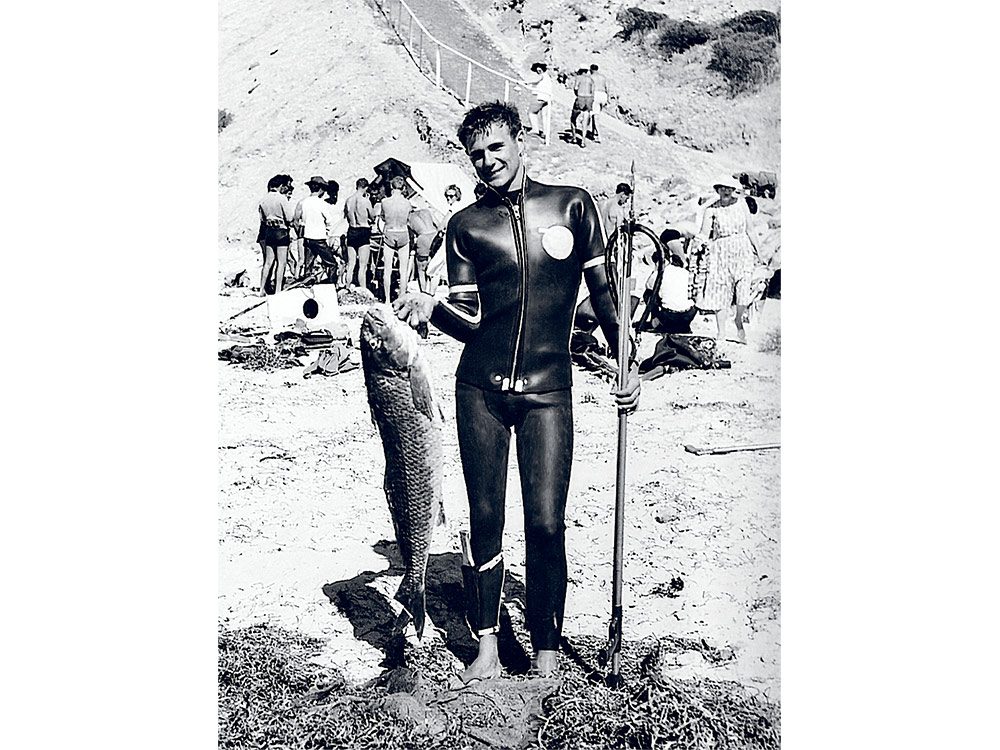

Forty of us—each with black rubber suits and flippers, glass-windowed face masks, snorkels, lead-weighted belts and spearfishing guns—were waiting for the referee’s 9:00 a.m. whistle to announce that the annual South Australian Spearfishing Championship competition had begun. We all had five hours to bring the judges a bag of fish. The winner would be determined both by total weight and by number of different species.

I was confident I’d do well. I’d taken the 1961–62 competition and was returning as the reigning champion. I had promised Kay that this would be my last competition. I meant to clinch the title and then retire in glory, diving only for fun from then on—hopefully joined by Kay. I was 23 and in peak shape after months of training. All the contestants were “free divers,” with no artificial breathing aids. I’d trained myself to dive safely to just over 30 metres and to hold my breath for more than a minute without discomfort.

These are the 13 things lifeguards wish you knew.

Meeting the Great White

At the whistle blast we waded into the surf. Each man towed a float behind him, attached to his leadweight belt. We would attach our fish to these floats immediately on spearing them, hoping their blood wouldn’t attract the always hungry and curious predatory sharks that prowl the deeper water off the South Australian coast. Lesser sharks—like the bronze whaler and grey nurse—are familiar to skin divers and aren’t aggressive.

Fortunately, great white, or “white death” sharks, caught by professional fishermen in the open ocean, are rarely seen by skin divers. Still, as a precaution, a patrol boat criss-crossed our hunting area, keeping a lookout. The day was bright and hot. An offshore breeze flattened the wave tops, but it disturbed the water on the reef. Visibility under the surface would be poor because of the previous day’s strong winds.

This makes life difficult for spear fishermen. In murky water, a diver is often too close to a fish once he realizes it’s there—and scares it away before he can get set for a shot. By 12:30, when I towed a heavy catch of parrot-fish, snapper, snook, boarfish and magpie perch to the beach, I could see from the other piles that I must be well up in the competition. I had 27 kilograms of fish on shore, comprising 14 species. It was now 12:35, and the contest closed at 2:00 p.m. As fish naturally grew scarcer in the inshore areas, I had wandered just over a kilometre out for bigger and better game.

On my last swim in from the section of the reef where it plunges from about seven metres to 18 metres in depth, I had spotted quite a few large fish near a big, triangular-shaped rock I was sure I could find again. Two of these fish were dusky morwongs, or “strongfish.” Either of these would be large enough to tip the scales in my favour, and one or two more fish of another variety would sew things up for me, I decided. I swam out to the spot I’d picked, then rested face down, breathing through my snorkel as I studied through my mask the best approach to the two fish sheltering behind the rock. After several deep breaths, I held one, swallowed to lock it in, turned over and dived. Swimming down and forward, so as not to spook my quarry, I quickly rounded the large rock. Not five metres away, the bigger dusky morwong, a beauty of at least nine kilograms, was browsing in a clump of brown weed.

I glided forward, hoping for a close shot. My arms were extended in front of me—my left for balance, my right holding the gun, which was loaded with a stainless steel shaft and barb. I drifted easily over the short weeds and lined up for a perfect head-and-gill shot, but…

How can I describe the sudden silence? It was a perceptible hush, even in that quiet world, a motionlessness that was somehow communicable deep below the surface of the sea. Then something huge hit me with tremendous force on my left side and heaved me through the water. Now the “thing” was pushing me forward with wild speed. I became immediately nauseous. The pressure on my back and chest was immense, and I felt as if my insides on my left were being squeezed over to my right side. I had lost my face mask and couldn’t see in the blur. My spear gun was violently knocked out of my hand The pressure on my body seemed to actually be choking me. I tried to shake myself loose but found that I was clamped as if in a vise. When my mind came into focus, I realized my predicament: a shark had me in its jaws.

I couldn’t see the creature, but it had to be huge. Its teeth had closed around my chest and back, with my left arm over its head. I was being thrust face down ahead of it as we raced through the water.

Although dazed with the horror, I still felt no pain. In fact, there was no sharp feeling at all except for the crushing pressure on my back and chest. I stretched my arms out behind and groped for the monster’s head. Suddenly, miraculously, the pressure was gone. The creature had relaxed its jaws. I thrust backward to push myself away, but my right arm went straight into the shark’s mouth.

As I wrenched my arm loose from the shark’s jagged teeth, I felt pain I could have never imagined. But I had succeeded in freeing myself. I knew the shark would come back for me. A fin brushed my flippers and then my knees touched its side. I wrapped my legs and arms around the monster, hoping wildly that this manoeuvre would keep me out of its jaws.

I scraped the rocks on the bottom. Now I was shaken violently from side to side. I pushed away with all my remaining strength. I had to get back to the surface.

When I reached it, the water was crimson with my blood. The shark breached a few metres away. Its body was like a great rolling tree trunk, but rust coloured, with huge pectoral fins.

The great conical head belonged unmistakably to a great white. Here was the white death itself!

It took 70 strangers to rescue these two boys from a riptide.

The fight to the surface

The shark began moving toward me, and terror surged through my body. I was alone in the fearful monster’s domain; here the shark made the rules. I was no longer an Adelaide insurance salesman. I was simply a squirming something-to-eat.

As the shark prepared to attack again, I worried I would die in agony when it struck. I could only wait. I breathed a hurried little prayer for Kay and the baby and prepared to kick at the monster’s head.

But, strangely, the creature veered away the moment before it reached me, the slanted dorsal fin curving off, just above the surface. Then my fish and float began moving rapidly across the water.

The slack line tightened at my belt, and I was being pulled forward and under the water again. At the last instant, the shark had swallowed the fish and the float instead of me and somehow got tangled in the line. I tried to release my weight belt, to which the line was attached, but I couldn’t find the buckle. I was being towed very fast now, about 10 metres below the surface, and my left hand fumbled helplessly at the release catch.

Surely I’m not going to drown now, I thought. Then the final miracle occurred: the line suddenly broke, and I was free once more. All I could scream when my head reached the surface was: “Shark! Shark!”

It was enough. Now there were voices, familiar noises, then the boat that I’d been praying would come. I gave up trying to move and relied on them to help me. Somebody kept saying, “Hang on, mate. It’s over. Hang on.”

The men in the patrol boat were horrified at the extent of my injuries. My right hand and arm were so badly slashed that the bones lay bare in several places. My chest, back, left shoulder and side were deeply gashed. Large pieces of flesh had been torn aside, exposing my rib cage, lungs and upper stomach.

Police manning the highway intersections for 54 kilometres got our ambulance through in record time. The surgeons at Royal Adelaide Hospital were scrubbed and ready. When I arrived on the operating table, I remember watching the huge silver light overhead grow dimmer. The next thing I recall is opening my eyes and seeing Kay and my mother alongside my hospital bed.

I said, “It hurts.” Kay was crying. The doctor walked over and said, “He’ll make it now.”

Don’t miss these fascinating (and reassuring) facts about shark attacks.

After the attack

Rodney Fox received a total of 462 stitches in his chest and 92 in his right arm. After a year of intense rehabilitation, he eventually returned to the sea. Fox continued to skin dive, though not competitively. Despite fearing sharks, Fox did not want to see them be senselessly killed.

His attack inspired him to learn more about the creatures and to help others do the same. During a trip to the Adelaide Zoo in 1964, while watching the caged lions, he developed the idea for a protective steel cage that could be lowered into the water over the side of a boat. Divers could float inside the cage, he thought, allowing them to get close to sharks while remaining safe from attack.

Fox eventually designed the cage and had it built. In 1965 he led the first-ever “shark cage” diving expedition, footage from which was used to make the film Attacked By a Killer Shark. Nearly a decade later, he was approached by the producers of Jaws, who requested help filming live underwater footage of great whites.

Today Fox is 78 and continues to dive both recreationally and professionally. The attack ultimately gave him a view into another world. He has consulted on more than 80 films and has travelled the globe giving lectures about sharks and his relationship to them—meeting many wonderful people along the way.

In the mood for another nail-biter? Read the terrifying tale of the helicopter pilot who was stalked by a polar bear!