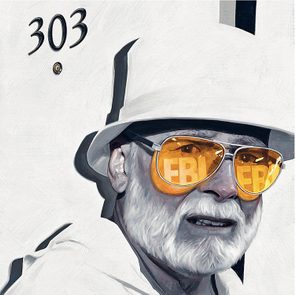

This Doctor Used the Wrong Sperm—And Sometimes His Own—To Impregnate Patients

Now the children he created want answers.

Kat Palmer was in Grade 9 biology when she began to doubt everything. The day’s lesson was on basic genetics and her teacher explained that the odds of two blue-eyed parents giving birth to a brown-eyed child were extremely remote. When she got home, Palmer broached the topic with her mother, Janet, who always knew this moment was coming. In the late 1980s, Janet and Kat’s father, Lyon, had wanted, very badly, to have a baby, but biology refused to cooperate. The Palmers, who lived in Ottawa, were thrilled to book an appointment with Dr. Norman Barwin, a local fertility specialist known as the “Baby God.” Out of a selection of possible donors, the Palmers chose a German-Irish medical student who played cello. Kathryn Rose Palmer was born on January 31, 1991 with coffee-bean eyes, a thick tuft of dark hair, and a determined jawline that everyone said looked like Lyon’s.

Kat and Lyon had always been close. So while she was shaken by her mother’s revelation, she decided this wouldn’t fundamentally change her relationship with the man who raised her. At the time, she didn’t have much interest in learning anything more about the sperm donor.

Mostly she didn’t think of him at all, though she did start to make little connections: her love of the performing arts and her talent as a musician (Kat would later study at Victoria’s Canadian College of Performing Arts) must come from her cello-playing bio-dad. “I had no idea that I was building my identity around a lie,” she now says.

A lie that, once uncovered, revealed a decades-long deception. It wasn’t until 2014 that the Palmers learned Janet was one of more than 100 women who had been impregnated at Barwin’s clinic with the wrong sperm. In some cases, the specimens came from men who were not the agreed-upon donor; in other cases, from the Baby God himself.

In 2016, Kat Palmer was among the first claimants to join a class action lawsuit against Barwin. By the time the unprecedented, $13.375-million settlement was reached last November, it included 226 plaintiffs (including children, mothers, partners and donors). The settlement is believed to be the first of its kind and could establish a precedent for similar civil charges. But it doesn’t address the systemic failures that allowed Barwin to practise, largely unfettered, for nearly 40 years. And it does nothing to appease donor-conceived Canadians who say the Barwin case highlights a culture of secrecy that denies them basic rights. The case also raises troubling questions about a medical establishment that prioritizes the interests and reputations of physicians over the needs of patients. Like Palmer, children conceived at Barwin’s clinic are left to wonder about the motivations of a doctor whose deity status obscured a devastating reality.

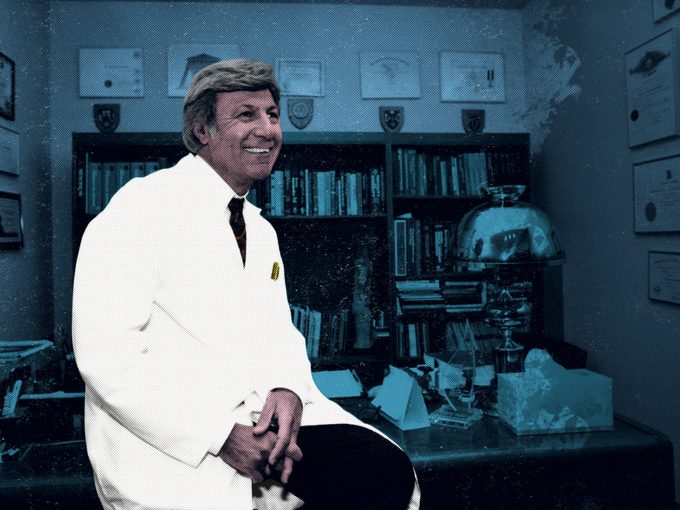

When Kat first found out that Lyon Palmer wasn’t her biological parent she didn’t think that DNA mattered. Today she feels differently: “Of course DNA matters. If it didn’t, this whole situation never would have happened in the first place.” And she’s right. Many aspiring parents challenged by infertility dream of shared genetics: the same deep-set gaze or determined jawline. Barwin’s ability to outmanoeuvre Mother Nature kept him in constant demand. Between the mid-1970s and the late aughts, he impregnated hundreds of women using artificial insemination. His success rate (Barwin claimed 76 per cent with fresh sperm and 63 per cent with frozen) spoke for itself. If that success bred a sense of imperviousness, it was hard to recognize under the white coat and soft-spoken, gentle veneer.

Who is Dr. Barwin?

Born in South Africa, Barwin earned his university degree and married his wife, Myra, before moving to Northern Ireland to complete his medical training. In Ireland the couple had four children and, in 1973, relocated to Canada, drawn by its progressive reputation and the offer of a job running the high-risk pregnancy unit at Ottawa General Hospital. But he left that position in 1984 after failing the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada gynecological exam multiple times. From there he launched his private practice, the Broadview Fertility Clinic, bringing many of his loyal patients with him.

Barwin was politically engaged, at the forefront of reproductive rights and an advocate for LGBTQ communities long before the medical establishment had come on board. In the early ’70s, he was among the first to perform gender- affirming surgery and contributed to some of the first ever textbook chapters on this emerging science. In the late ’70s, he set up the first sexual health clinics in Ottawa’s public high schools. His four children decorated an old school bus— the “Sex Bus”—which drove around Ottawa distributing information on sexual health and anti-smoking. In 1988, he campaigned against Bill C-43, which would have seen abortion added to the criminal code. He also served as president of Planned Parenthood and of the International Society for the Advancement of Contraception. A glowing 2001 profile in the Ottawa Citizen described Barwin, in an inadvertent foreshadowing of the revelations to come, as a physician who “believes in doing whatever he feels is necessary to help his patients, regardless of taboos or conventions.”

In 1995, a couple named Loree-Ann Huard and Wanda Cowton sued Barwin when they found out their daughter was not a genetic match to their intended donor. The case was settled privately in 1998, a year after Barwin was awarded the Order of Canada and praised for his “profound impact … on both the biological and psycho-social aspects of women’s reproductive health.”

Also in 1995, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), the self-governing body responsible for overseeing the conduct of doctors, contacted Barwin about the Huard-Cowton complaint. He responded that he had taken steps to ensure such errors would be avoided. If that is true, the measures weren’t successful.

In 2008, another former Barwin patient, Trudy Moore, learned her daughter (born by surrogate) was not a genetic match to the intended donor (her husband). When Moore asked Barwin for an explanation she was told that her husband’s sample may have been contaminated by a sample from a sperm bank. She consulted the Donor Sibling Registry, which connects individuals conceived with the same genetic material, and was referred to Jaqueline Slinn, a former Barwin patient who was also under the impression that her daughter, Bridget, was conceived using the same sperm bank donor. Expecting their daughters to be genetic half-sisters, the two mothers tested their DNA only to learn that the girls weren’t related. Nor was either girl a match to other children conceived ostensibly using sperm from that donor. Moore and Slinn filed two separate $1-million lawsuits against Barwin: the former for malpractice and the latter for information regarding the donor, including a genetic sample from Barwin to rule him out as a potential father.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail, Barwin called the situation “my worst nightmare,” and claimed he was still “unable to find where the basic problem lay.” Both lawsuits were settled out of court and included non-disclosure agreements. In 2012, the CPSO ordered a disciplinary hearing. The following year, Barwin was found guilty of professional misconduct. The chair of the five-member panel described his “substandard failure to establish adequate safeguards,” suspended his medical license for two months and charged him $3,650 in costs—in other words, a wrist slap. But the publicity surrounding the hearing would capture the attention of a whole new group of Barwin’s victims, including Kat Palmer.

DNA Revelations

By 2012, Palmer had moved to Vancouver, where she worked in musical theatre. She still wasn’t particularly interested in meeting her birth father, but she was very curious about potential half-siblings. As an only child she had always dreamed of having a brother or sister. One day she broke down in tears watching an Anderson Cooper talk show about uniting long-lost siblings, and took this as a sign that it was time to do something. When she contacted Barwin’s clinic to learn more about the mysterious donor, she was told that, in accordance with provincial regulations, the clinic destroyed records after 10 years. Undeterred, Palmer sent a DNA sample to Family Tree DNA, one of many commercial genetic testing sites that have gained popularity over the last decade. She hoped the results would help her find siblings who shared her Irish-German donor. But when the results came back, she learned that she was almost certainly of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. For a brief moment, Lyon Palmer (who is Jewish) thought that perhaps, miraculously, he was the biological father. But further testing ruled this out.

Family Tree DNA did connect Palmer with relatives, all several degrees removed, which is how she ended up speaking on the phone with a third cousin. Palmer mentioned that she had been conceived at a clinic run by Dr. Norman Barwin. When the cousin later mentioned this to his mother, she paused, feeling the name sounded familiar. A quick record search comfirmed she had a distant relative named Norman Barwin.

Long before any of these revelations, the Palmer family had known Barwin socially. It was impossible to be a member of Ottawa’s Jewish community and not be aware of Barwin and his good works. Kat had even taught one of Barwin’s grandchildren at an after-school theatre program.

That her pupil might, in fact, be her niece was something Palmer was beginning to process. She started to follow Barwin’s family members on Instagram, marvelling at physical similarities and how many worked in the arts. Her urge to connect with these people— her biological family—felt somehow more important than whatever anger she felt towards Barwin.

On August 13, 2015, Palmer sent an email to Barwin: “I am writing this letter because I have found information that makes me believe that I am, genetically, your descendant.” He wrote back immediately and soon the two spoke on the phone. During their conversation, Barwin agreed to a DNA test. Palmer isn’t sure why he was so quick to hand over the genetic smoking gun. “I think I seemed so non-threatening. And then at the same time, I had him backed into a corner.”

When the test confirmed that Barwin was Palmer’s biological parent, he attempted to explain the situation. He had purchased new equipment in 1990—perhaps it had been contaminated during testing. Palmer thought that sounded implausible but wanted to avoid conflict in the hopes of connecting with her half-siblings. That hope was dashed when Barwin explained that learning of Kat’s existence would be too difficult for his wife and four children, and his dozen-plus grandchildren, all of whom lived in Ottawa. He sent Palmer an email: “My compensation for this inadvertent medical error is that you have been so successful in your career, but more importantly that you are a sensitive and special person.”

To Palmer, the response was a rejection, and also deeply narcissistic—like he was taking credit for her positive traits. She contacted Trudy Moore, whom she’d read about in media coverage of the 2013 disciplinary hearing.

Moore referred her to the law firm Nelligan O’Brien Payne LLP, which was preparing to launch a class action suit against Barwin. The suit accused him of using, without consent, the wrong semen for artificial insemination, and failing to safekeep semen entrusted to him. The main plaintiff was Rebecca Dixon, a 25-year-old civil servant who lived in Ottawa. She learned Barwin was her biological father after she was diagnosed with an autoimmune condition that doesn’t run in her family.

After being connected by their lawyers, Palmer and Dixon began texting almost daily. Their bond was immediate—they discovered they had attended the same Ottawa high school, that they both talk with their hands and love music. Four months later they met in person at Pearson International Airport. Palmer ran out from behind the arrivals door. Dixon held a sign that read “Welcome Sister” in multicoloured bubble letters, and the two women attempted to make up for more than two decades of lost hugs in one epic embrace.

Palmer and Dixon soon learned about a half-brother, James, and a half-sister, Marie, plus 24 others, ranging in age from 30 to 50-plus. Some have connected through the class action lawsuit, others through genetic testing. The group jokes that they need to brace themselves for more siblings after Christmas, when DNA kits are often given as gifts. Last summer, 30 of the half-siblings gathered at Dixon’s home for an atypical family reunion. “The relationships we have developed are amazing,” says Palmer. “But that doesn’t make what happened okay.” She gets angry when people act like nothing bad happened. Can’t you just be grateful you’re alive?

It’s a conundrum, but not one Dixon is willing to spend a lot of time with. “You can think about it in circles forever,” she says. “Or you can just accept that I can be happy that I’m alive and that what he did was a terrible thing. Both things can be true.”

Does This Happen Often?

Fertility fraud is shockingly common. Dr. Donald Cline, the Indiana fertility specialist and subject of the recent Netflix series Our Father, impregnated more than 50 women with his own sperm in 10 years. Dr. Quincy Fortier of Las Vegas used his own sperm to impregnate at least 24 patients from 1950 to the late 1980s. In 1992, Dr. Cecil Jacobson of northern Virginia was convicted on numerous counts of fraud and perjury for inseminating unwitting patients with his own sperm.

“It’s not that it is happening more, it’s that we are able to catch it,” says Sara Cohen, a Toronto fertility lawyer. The rise of commercial DNA testing and donor-conceived sibling registry websites has brought a previously difficult to detect misdeed into the foreground. At the dawn of artificial insemination in the 1940s, record-keeping was not the norm. Doctors would often solicit “donations” from medical students. Prospective parents were happy to get “future doctor” sperm and the thinking was that the lack of a paper trail between donor and child was best for everyone involved. Although not officially sanctioned, doctors using their own sperm was common enough that two percent of American fertility doctors said they engaged in the practice in a 1980s survey.

In the early ’70s, when Barwin established a sperm bank at Ottawa General Hospital, he made no secret of the fact that it was largely stocked by his medical students (he said nothing about using his own sperm). By the time he opened the Broadview Fertility Clinic in the mid-1980s, the culture was beginning to change. With artificial insemination now a mainstream practice, a regulated sperm bank industry emerged to serve a growing market.

Did Barwin freeze his own samples? Or did he produce live sperm (known to be slightly more effective) in the short window before an appointment? Were his decisions guided by negligence? Malice? A misguided sense of benevolence? These are the questions that haunt Palmer, but she believes she and the other Barwin descendants are, in some ways, luckier than many of her co-plaintiffs who haven’t been able to track the identity of a biological father. “It’s not the answer we want,” she says, “but at least we have one.”

What’s Being Done To Prevent It?

In 2004, Canada passed the Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHRA), regulating how donated sperm is tested and processed, but a constitutional challenge by the Province of Quebec has resulted in a stalemate, and it remains unclear which level of government has the authority to regulate assisted reproduction. Meanwhile, compliance is, at best, spotty. “There is a joke in the donor-conceived community that it is hard to find a clinic that hasn’t had a fire or a flood,” says Kevin Martin, co-founder of the Donor Conceived Alliance of Canada. Donor-conceived individuals face a frustrating battle when looking for their biological information. The organization is pushing the government to update the AHRA with requirements for expanded donor health screening, record-keeping for up to 110 years, limits on how often a single donor can be used and, above all, a ban on donor anonymity. The thinking there, Martin explains, is that a donor-conceived individual’s right to their biological information should outweigh a donor’s right to anonymity. I ask Martin how rules around anonymity would have made a difference with Barwin—it’s not like he would have written his own name on the form. Martin says that it’s about deception thriving in dark corners: “Anonymity is what allowed Barwin to do the things he did, to lie and obfuscate with zero accountability. Anonymity is how this happened. Transparency is what can fix it.”

Indeed, a culture of silence could explain how Health Canada inspected Barwin’s clinic in 1999 and 2002, and found numerous infractions, including mishandled and missing sperm. Despite this, he wasn’t shut down. Worse, the CPSO claims it was never made aware of these findings.

Paul Harte, a medical malpractice lawyer, argues that the self-governing College system for doctors is inherently biased. “There’s a tendency to protect your own,” he says. Harte would like to see the introduction of an independent body similar to the Securities Commission. The Barwin case, he says, is a good example where you have, on one side, a very vulnerable group (people struggling with infertility) and then on the other side a significant financial incentive. “Inevitably there is going to be a certain amount of corner-cutting to ensure success,” he says.

Many experts believe that classifying fertility fraud under the criminal code is an important step towards justice in Canada. In the United States, some states have created laws against it. Texas, for instance, made insemination with sperm the patient did not consent to a form of sexual assault.

What Now?

Norman Barwin retired in 2014. After investigating complaints that Barwin had used the wrong sperm, or his own sperm, at his clinic, the CPSO revoked his medical license in 2019 and fined him $10,730. Barwin pled no contest to the allegations. Last November, an Ontario Superior Court judge approved the agreed-to $13.375-million settlement from the class action suit, which included 17 plaintiffs who were conceived using Barwin’s own sperm. The settlement will be paid out by the Canadian Medical Protective Association, which represents doctors subject to legal actions. Because the case was settled out of court, Barwin made no admission of wrongdoing and offered no explanation.

There is this story, though: In 2000, Barwin, a life-long runner, competed in the Boston Marathon, finishing 14th in his age group. Later inspection revealed that he had missed check-points and had cheated his way to a strong finish. The incident was covered by Ottawa media, with many of Barwin’s former patients coming to his defence. But the following year, he was caught cheating again at the National Capital Marathon in Ottawa, the behaviour of a man for whom the rules simply do not apply.

When Palmer and Dixon first learned the truth about their conception, they asked themselves if they were the products of one man’s deranged plot to populate the earth with his descendants. Now they are more inclined to see the story, their story, in shades of grey. The man who is responsible for their existence was a doctor who would do anything for his patients up to and including things to which those patients would never consent. He was a champion of women’s rights who also violated the rights of women in the most intimate and offensive ways imaginable. A “Baby God” and a monster. And while there is an inclination to see these dichotomies as either-or, for the people who share Barwin’s DNA it is perhaps better, and easier, to believe that both things can be true.

Next, check out 10 Canadian true crime podcasts worth adding to your playlist.