Flight Training Facilities of WWII Still Dot the Prairie Landscape

Canada’s wide-open spaces away from enemy interference were ideal for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

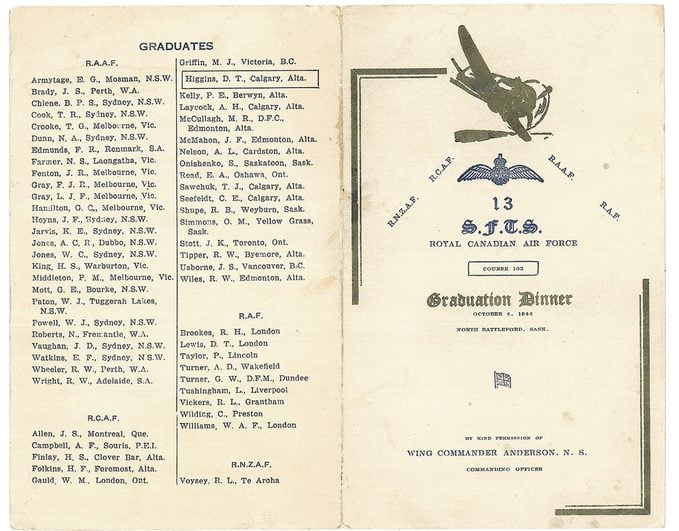

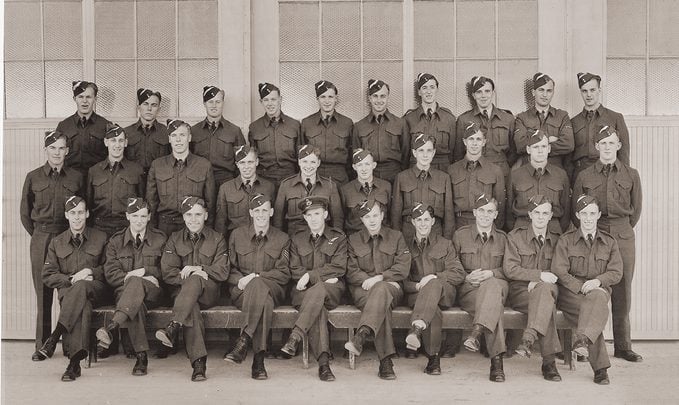

My father, R. Blaine Shupe, was one of thousands of Commonwealth pilots to graduate from the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada during the Second World War. Canada’s wide-open spaces away from enemy interference made our country ideal for air training, and pilots from Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada earned their wings at these facilities.

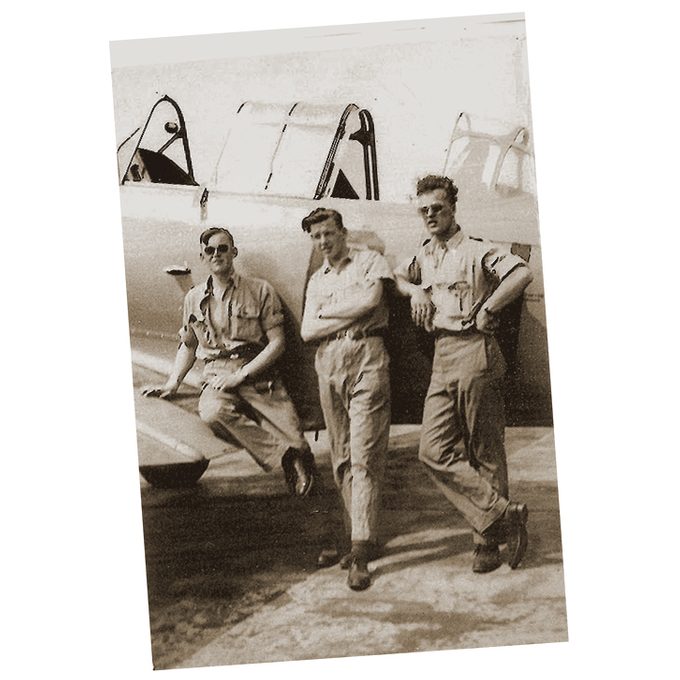

A program from Blaine’s fancy graduation dinner is one of just a few precious keepsakes we have from this time. Another heirloom is a photograph of Blaine and two others standing around a North American Harvard II training aircraft, a primitive predecessor of the CT-156 Harvard II trainer the Royal Canadian Air Force uses today. The confidence of the handsome young men, augmented by aviator sunglasses, reminds me of Tom Cruise and his pilot buddies posing beside their F-14 Tomcats in Top Gun.

Flying is not to be taken lightly, however. Training accidents in recent years, including the crash of a CT-114 Tutor in May of 2020 in Kamloops, B.C., which claimed the life of Capt. Jennifer Casey, remind me of a history lesson my father gave me in the early ’70s, when I was a young lad growing up in Weyburn, Saskatchewan. This three-hour excursion with Dad sparked a lifelong interest in aviation history, but, more importantly, made me appreciate the tremendous human cost of war. I would remain forever grateful for his military service and guidance growing up.

Blaine received his wings in October 1944 at #13 Service Flying Training School in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, one of more than 100 such schools in Canada during the war. There was even one located right in our hometown of Weyburn—#41. Blaine took me on a fascinating tour of the Weyburn base, located at present-day Weyburn Airport, and its relief landing field near the small town of Halbrite.

Touring the Old Flight Training Sites With My Father

The tour began almost as soon as we got into the car, when Blaine pointed out a strange-looking apartment block, explaining that it was once an enlisted men’s barracks. Soon after, I would proudly bring this fact to the attention of a friend who lived there.

Unlike most of the other bases on the Prairies, many of Weyburn’s structures were kept standing after the war, converted into various medical, educational, manufacturing and storage facilities over the years. Some of them, such as a couple of hangars, have hardly changed in appearance at all. Two of the best-preserved buildings are the headquarters building, which has been transformed into a sprawling residence, and the former supply depot that now serves as a functional home with character, and large art studio. The structure I remember best from my visit with Blaine is the two-storey 25-yard range, which looks like a concrete pillbox and is still very much intact. Graduating classes from Western Christian College customarily decorated the drab exterior of “The Rock,” as they called it, with colourful murals.

From the Weyburn base, we drove to the relief landing field near Halbrite, where we could examine the few remaining artifacts at our leisure. Just off the main road is a rectangular, earth-covered concrete bunker that Blaine said was probably used to house munitions and flammables. While he looked on, I scrambled up one of its steep sides and was just waiting for a soldier to emerge from one of the submarine-like hatches to see who was moving around on top of his flat roof. Even more interesting is a smaller but very solid fortification about 200 yards northwest. It only juts a couple of feet above the ground, close to where the runway used to be, but is easily visible from several hundred yards away. Blaine wasn’t sure what this stone and concrete bunker was used for. He thought it might have been the floor of a control tower at one time. It has four large, heavy-steel hatches on top that have since been opened and deliberately flooded to the top rung for safety reasons. The only other structure to see on the site was an enormous wooden hangar. Blaine spent quite a while looking around its huge interior and pointed out a few items left behind after the war. I think he was surprised at how well-preserved everything was inside. It reminded him of the hangars he used during his own training. Blaine said the training facilities were very similar to those in North Battleford. Today, its structures are an almost ghostly feature of the Prairie landscape.

The Veteran’s Section

I found our last stop a bit unsettling. We came to a halt near the Veteran’s section in the northwest corner of Hillcrest Cemetery, just south of town. Buried together in two short rows, surrounded by dozens of Saskatchewan veterans of both World Wars and Korea, are 17 RAF airmen who perished in training accidents flying out of #41 SFTS between March 1942 and December 1943. These men are included alongside 155 air personnel from England and other Commonwealth countries killed while training in Saskatchewan in a magnificent book commemorating Saskatchewan’s war dead, Age Shall Not Weary Them. Looking at the gravestones, you are immediately struck by the young age of most of the men. Some share the same date of death, often experienced officers and young pupils who were in the same crash. Over 1,700 airmen never lived long enough to see their own graduation day. An average of 12 servicemen died every week during the war in training accidents.

Blaine explained the air force suffered an exceptionally high mortality rate because of the perilous nature of its training. Certain airborne manoeuvres could be very challenging for inexperienced pilots. Many accidents, however, were strictly mechanical or weather-related. That was the saddest part of all, in Blaine’s opinion. Over one-quarter of all Allied air force casualties during the war were non-combat related. Seventeen fatalities and even more crashes in the span of just 21 months in a small rural community like Weyburn would have been acutely felt.

One grave that resonates with our family is that of Pilot Officer Harry Whittaker of Somerset, England, who died in October 1942 at 21 in the same crash as his instructor, Flight Lieutenant Harwood Williams of Leeds. My uncle, Jack Shupe, remembered Harry from his days playing ice hockey and described his sudden death as a shock, even in the aftermath of the Dieppe Raid that had shaken the entire province a few weeks earlier, with many casualties from Saskatchewan. Incidentally, my grandfather Joe Warren was the mayor of Weyburn during the war years and said that being a part of the delegations to visit some of the fallen soldiers’ parents and wives after the Dieppe Raid was one of the most difficult duties he had to perform.

The last British airman stationed in Weyburn to die in a training accident was 20-year-old Pilot Officer William Hughes of Hornchurch, Essex, on December 20, 1943.

Buried right next to him 59 years later is distinguished Weyburn native and Royal Military College graduate, Juli-Ann Dawn MacKenzie. Capt. MacKenzie and one other RCAF airman were killed when their CH-146 Griffon helicopter crashed near Goose Bay, Newfoundland, in July of 2002. This is yet another tragic but poignant reminder of the tremendous risk and sacrifice air force services endure to this day.

Don’t miss these Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.