A Terrifying Brush With Death at the Brink of Niagara Falls

If the hydro workers didn’t act fast, Sherry Vyverberg would be swept over the falls—or caught in the swirling blades of the powerhouse turbines. A Reader's Digest Classic, originally published in July 1984.

Monday, May 30, 1983, was a holiday in the United States—Memorial Day—and 20-year-old Sherry Vyverberg of Rochester, New York, decided to spend it at Niagara Falls with friends. Tall, with blue eyes and long, fair hair, Vyverberg had just finished a year of community college, the first step toward a nursing degree. Since she had to be back in Rochester by 3 p.m. for her job as a nursing assistant, she left home early and picked up her boyfriend, Keith Gandy, 22, and their friends Greg Grant, also 22, and Mike Jarocki, 26.

It was a bright, cool day, and all four were in high spirits. After a 90-minute drive, they crossed the Rainbow Bridge and had breakfast at a restaurant on the Canadian side of the border.

At 8:15 a.m., they drove along the Niagara Parkway and parked beside the Toronto Power Generating Station, an abandoned generating plant on the west bank of the Niagara River, 580 metres upriver from the falls. Gandy had broken his ankle a week earlier. Now, with his leg in a knee-high cast, he stood leaning on crutches beside the stone powerhouse, talking with the other two men.

Meanwhile, Vyverberg, dressed in a pink track suit, stepped around a metal railing by the powerhouse and crossed a small patch of grass to an ornamental barrier with a 60-centimetre-wide concrete ledge overlooking the water. Then, to get a closer view of the river, she walked a few metres along the ledge.

From her precarious perch, she looked downriver, where the semicircular crest of the Horseshoe Falls spanned the width of the river, from Goat Island to the Canadian shore. Dropping close to 60 metres to the furious turbulence below, the enormous waterfall roared like muffled thunder as it threw up its perpetual cloud of spray. Vyverberg knew that the Niagara was one of the most spectacular rivers in the world. What she did not yet realize was that it was also one of the most dangerous.

Directly below her, six metres down, water spilled from the sluiceway of the old powerhouse. Vyverberg peered down at it. Suddenly, she lost her footing and fell from the ledge.

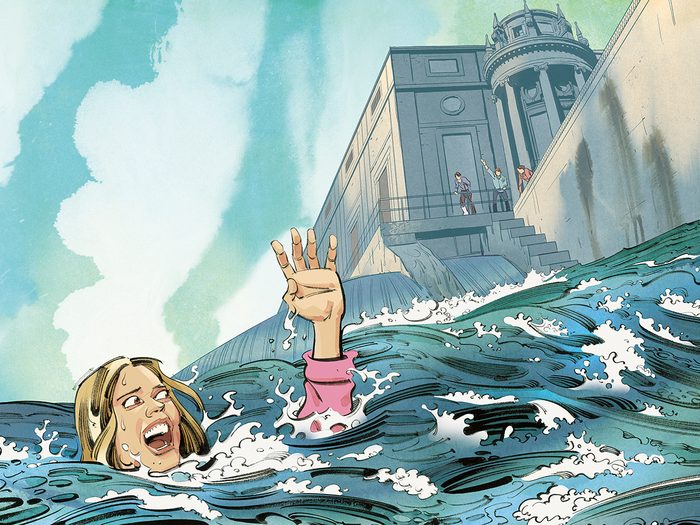

She felt the shock of plunging into eight-degree-Celsius water and the force of the current sucking her deep down. Somehow she managed to hold her breath underwater and, when she reached the surface, to gasp for air. But again and again, the churning water pulled her under.

On the bank near the ledge, Jarocki had seen Vyverberg lean forward and then topple headfirst. This isn’t real, he thought. He cried, “She’s in!” With Grant, he scrambled down the bank and stood on the shoreline watching helplessly. For an instant, Vyverberg’s head bobbed up, then her feet, then she disappeared under the whitewater. Jarocki thought, There’s nothing we can do. How can we tell her mother?

From the bank, Gandy yelled, “She’s downstream!” Vyverberg had been caught by the river’s current and pulled 15 metres offshore. Now she was roughly 500 metres from the brink of the falls. Through she was a keen skier and hiker, Vyverberg could scarcely swim. Paddling with her hands to keep afloat, she felt the current tugging at her legs like some powerful monster. I’m going to die, she thought. I’m going over the falls.

With Jarocki close behind him, Grant scaled the cliff and raced along the bank, stripping to his underwear as he ran. When he drew level with Vyverberg, she was more than 30 metres out, and much closer to the falls. He clambered down to the river and dived in, the cold water gripping his body. Grant was able to swim just five metres before being swamped by torrential rapids. I can’t make it, he thought, and struggled back to the shore.

While Vyverberg was being swept downstream, three employees of Canadian Niagara Power were driving along the parkway to the company’s Rankine Generating Station, a working powerhouse halfway between the old Toronto Power Generating Station and the falls. Carpenter Joe Camisa, 55, was at the wheel of their truck, with John Marsh and Pete Quinlin in the cab beside him.

Ironworkers by trade, Marsh and Quinlin were old friends and riggers for CNP, where they slung cables around heavy machinery that needed to be lifted and moved. Forty-year-old Quinlin was married, with four children. Marsh, 37, was wiry, with sandy reddish hair and a moustache. A bachelor, he had always loved sports that tested his swiftness and skill.

As the hydro crew drove past the Toronto Power Generating Station, they saw a young man limping toward them, waving his arm wildly and shouting.

“There’s a girl in the water!” cried Gandy. He had abandoned his crutches and hobbled the short distance to the parkway, hoping to flag down someone who could save Vyverberg.

The three men jumped out and raced to the river. Vyverberg was nowhere in sight. Then, from the asphalt path running along the bank, Marsh spotted her head floating like a beach ball 45 metres from the shore.

“She’s way out!” he yelled to Quinlin. “We’re never going to get her out there.” Sick with helplessness, the two men watched as the swift current carried Vyverberg away. Marsh thought, I’d rather jump in than watch her go over the falls and spend the rest of my life second-guessing myself.

Then he remembered the weir, a curved concrete wall running just below the surface of the river from the Rankine Generating Station to a point 130 metres offshore. The weir was designed to divert water away from the falls and into the turbines under the powerhouse. Vyverberg was now just inshore from the river end of the underwater wall.

Marsh had grown up beside the river. “I fish here a lot,” he told Quinlin. “Out where she is, the current is going to the falls. But if I cast out there, nine times out of 10 my line drifts inside the weir, down by our powerhouse. If she doesn’t go over the wall, she’ll come drifting into the powerhouse.”

Glancing back to the parkway, he saw a police cruiser passing and shouted, “There’s a cop. Flag him down!”

Quinlin waved furiously at the officer and yelled, “Get some help. We’ve got a girl in the water!”

Constable James Caddis of the Niagara Regional Police Service quickly called his dispatcher and asked for fire trucks and rescue equipment. But Vyverberg was now only 245 metres—roughly the length of two football fields—from the brink of the falls, and time was running short.

If the current swept her over the weir, no one could save her. If she drifted with the flow to the powerhouse, as Marsh hoped, they might have one brief chance to catch her before she was carried through the intake gates to the turbines—where she would be cut to ribbons—or over the sluiceway at the base of the weir and on to the falls.

Marsh and Quinlin had so often worked side by side that they instantly acted as a team. Quinlin was tying together two pieces of rope snatched from the back of the truck as they ran toward a narrow stone-and-concrete bridge that spanned the intake stream to the powerhouse. The men scram- bled over a steel picket fence and ran along the walkway. “Stay up! We’ll get you!” they called to Vyverberg. She couldn’t hear or see them, but she floated without struggling as the current carried her inshore.

Marsh told Quinlin, “I’ll go. You’re a family man. This is not the place for you.”

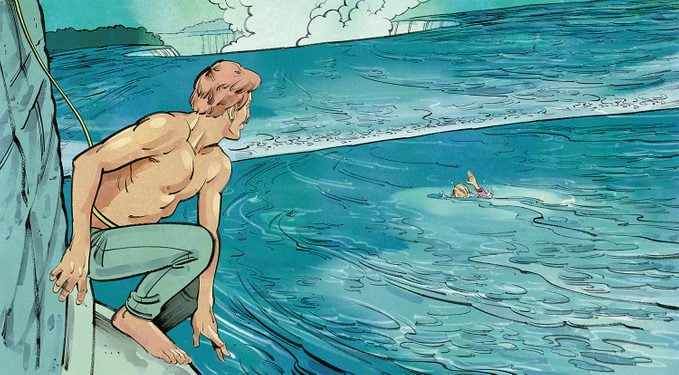

He pulled off his boots, jacket, sweater and shirt, while Quinlin tied one end of the rope to the handrail and the other in a running bowline looped around Marsh’s waist. Wearing only his jeans, Marsh climbed over the rail and dropped three metres to one of the concrete piers that supported the little bridge. He waited a few seconds, then said, “She’s as close as she’ll ever come.”

From the pier, Marsh dived in and swam toward Vyverberg as she drifted toward the weir. About 20 metres out, he’d reached the end of the rope, but he still couldn’t reach her. Swimming as hard as he could to stay where he was, he waited until Vyverberg floated closer, then made a desperate lunge and grabbed her by the hair. Pulling her backward toward him, he flung his arms around her and urged her to stay calm. Vyverberg was so exhausted that she only managed to gasp, “Thank you, God,” and to Marsh, “Thank you, too.”

On the shore, Vyverberg’s friends—and Marsh’s—were holding their breath. They saw Marsh seize Vyverberg and heard him yell, “Keep the rope tight and haul us in!” By now, Camisa and Jarocki were on the walkway beside Quinlin. Tugging together, the three men slowly dragged Marsh and Vyverberg through the water and up against a pier below the bridge.

“Hold it!” said Marsh. “Don’t let her slip back in. I’ve got hold of an iron bar down here. I’ll take the rope off of me and get it around her.”

After Quinlin pulled Vyverberg to safety, he dropped the rope back to Marsh, who slipped it over his head and shoulders and let himself be hauled up.

Vyverberg was in shock after her eight-minute ordeal. Her lips were blue, and her shivering body was numb with cold. As Jarocki flung his jacket around her, she began crying uncontrollably. But she was on her feet and walking toward the parkway with Constable Caddis when the emergency vehicles arrived: the fire-department rescue squad, an ambulance and three police cars. The paramedics wrapped Vyverberg in blankets, strapped her to a stretcher and lifted her into the ambulance. Jarocki climbed in beside her.

On the way to Greater Niagara General hospital, Vyverberg was still agitated. “Who saved me?” she kept asking. “Is anybody else hurt?” If someone has died trying to save me, that’s one thing I can’t live with, she thought. Repeatedly, Jarocki reassured her that everyone was okay.

At the hospital, Vyverberg was treated for shock and hypothermia and kept for two hours for observation and tests. In spite of her ordeal, her temperature and blood pressure were within normal limits, and X-rays showed no fluid in her lungs.

She was resting on a cot when Caddis came back to check her progress. Vyverberg asked her rescuer’s name. “John Marsh,” answered the officer. “And you’ve got a lot to be thankful for, that John Marsh was there.”

John Marsh wasn’t at the scene for long. He shrugged off his only injuries: the rope-burn bruises under his arms and around his chest. If Caddis hadn’t hailed him, Marsh and his co-workers would have driven away without revealing their names.

With self-effacing good humour, Marsh also tried to shrug off the accolades that followed, wondering what all the fuss was about. Among tributes from Canadian and American politicians came a letter from President Reagan commending him for his heroism. Marsh was awarded numerous medals and plaques, including the Carnegie Medal and the Royal Canadian Humane Association bronze medal. He was also awarded the Star of Courage by the Governor General.

As Constable Caddis said: “Just to tie that rope around you and jump into that river takes a lot of guts. One man in a thousand would do what John Marsh did.”

Check out more Drama in Real Life from the pages of Reader’s Digest Canada.