Buffy Sainte-Marie: Going Her Own Way

Shortly before sunset on the last day of June, Buffy Sainte-Marie strides onto the stage at the foot of Toronto’s city hall. Even at 76, the singer-songwriter comes across as the consummate rock star: tight black pants, studded jacket, a smile so bright it could power the curved towers looming in the background. Grinning at the crowd and its applause, Sainte-Marie is confident and cool, exuding an effortlessness that cannot be learned—hers has been earned through decades of hard work and diligence.

This performance is one part of Toronto’s contribution to Canada 150, a marathon of a party that hasn’t met with unanimity. Since January, and before, Indigenous people have voiced opposition to the festivities, contending that they erase the history of the land prior to 1867 and that Canada hasn’t given First Nations much reason to celebrate in the years since Confederation. Sainte-Marie, an Indigenous icon, has admitted she’s “of two minds” about the event in which she’s participating.

As she stands here, water protectors sit in a teepee on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, protesting Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples. Michèle Moreau, the executive director of the troubled National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, has just resigned from her post. The York Regional Police have taken over investigating the deaths of Tammy Keeash and Josiah Begg—Indigenous teens whose bodies were found in northern Ontario waterways—because an independent probe is investigating the Thunder Bay Police Service for “systemic racism.” Nerves are, to say the least, taut.

An expectant hum emanates from the audience as Sainte-Marie and her band take their places. Will she chastise the crowd? Will she castigate Canadians for their complacency? Will she reprimand Justin Trudeau and his government for their inaction? One thing is certain: she’s not going to stay quiet.

As if able to read the concertgoers’ minds, Sainte-Marie flashes a cheeky smile and launches into her 1964 song “It’s My Way”:

The years I’ve known

The life I’ve grown

Got a way I’m going

And it’s my way.

Sainte-Marie has been going her way since breaking into the music scene in her early 20s, consistently turning away from the more conventional, less controversial paths before her. Her boldness has paid dividends. During her half century in the public eye, Sainte-Marie has been the recipient of 14 honorary doctorates and reams of praise from contemporaries and critics; and won Junos, Grammys, an Academy Award for Best Original Song (the power ballad “Up Where We Belong”) and the Polaris Music Prize for 2015’s Power in the Blood.

But success hasn’t come without struggle or sacrifice. There was a time when her records were being released to very little fanfare, when her influence went unrecognized because the rest of the world couldn’t keep up. In the same way her ancestors were thriving on this land before settlers arrived, Sainte-Marie was breaking ground in art, education, activism and technology long before others came along to take the credit for “pioneering” those fields.

Through it all, Sainte-Marie has carried on, teaching those around her even as she helps map out the future of arts, education and Canada itself. One can’t help but wonder: where will she lead us next?

Buffy Sainte-Marie was born in 1941 on the Piapot Reserve in Saskatchewan’s Qu’Appelle River Valley. Orphaned in infancy, she was adopted by Albert and Winifred Sainte-Marie and raised in Wakefield, Mass. As one of the only Indigenous people in a mostly white community, she often felt isolated. Her parents responded by giving her creative freedom, through which she discovered a love of music early on.

“I used to lie on the floor with vacuum-cleaner headphones, listening to Swan Lake,” she says, recalling how she disassembled the household vacuum and connected the appliance’s tubes to the family record player to provide a more immersive sound.

At three years old, while other children were learning to dress themselves, Sainte-Marie was teaching herself to play piano. By 16 she had also tackled the guitar and was developing several different ways of tuning the instrument, generating sounds no one else was making.

Another significant interest—her roots—was less accessible. She knew she was Cree and that her adoptive mother was part Mi’kmaq, but she was also aware that Winifred had never had the chance to learn about that side of her ancestry. In their city, the most prominent Indigenous face was the scowling Wakefield Warrior, a local high-school mascot. Sainte-Marie knew there was more to her culture than the racist caricature glaring at her during sports games. If no one in Wakefield could teach her about it, she’d find someone who could.

In her late teens, she began taking trips to Saskatchewan to reconnect with her Cree community, where she was traditionally adopted by Emile Piapot and Clara Starblanket Piapot.

“They’re not blood relatives, we don’t think, but they could be,” says Sainte-Marie. Either way, the match was fitting in more ways than one. Emile was a son of the respected Chief Piapot, who had fought Canada on treaty rights and many other repressive policies, including a ban on the Thirst Dance, an important Cree ceremony.

The similarities between Chief Piapot and his adopted descendant went beyond birthplace. Both would be tireless defenders of their people’s rights; both would be visionaries—when one path to justice was blocked, they forged another; and both would be considered so dangerous, so powerful, that governments conspired to silence them.

“What I like most about Buffy is that she has always been unapologetically Indigenous,” says prominent Mi’kmaq lawyer, educator and activist Pam Palmater. “She has never tried to portray herself to be anyone but one of our people. That has always stood out in Canada, a country that has worked hard to make us adapt, change, abandon and assimilate. She is living proof that we are still here and proud.”

When Sainte-Marie first came to visit the Piapot Reserve, she had no inkling of what her future held, or of the generations she would inspire. All she knew was that she was part of a much larger history of Indigenous resistance—and she wanted to carry that tradition forward.

After graduating from the University of Massachusetts with degrees in education and oriental philosophy, Sainte-Marie considered two options: become a teacher on a reserve or travel to India to further her studies.

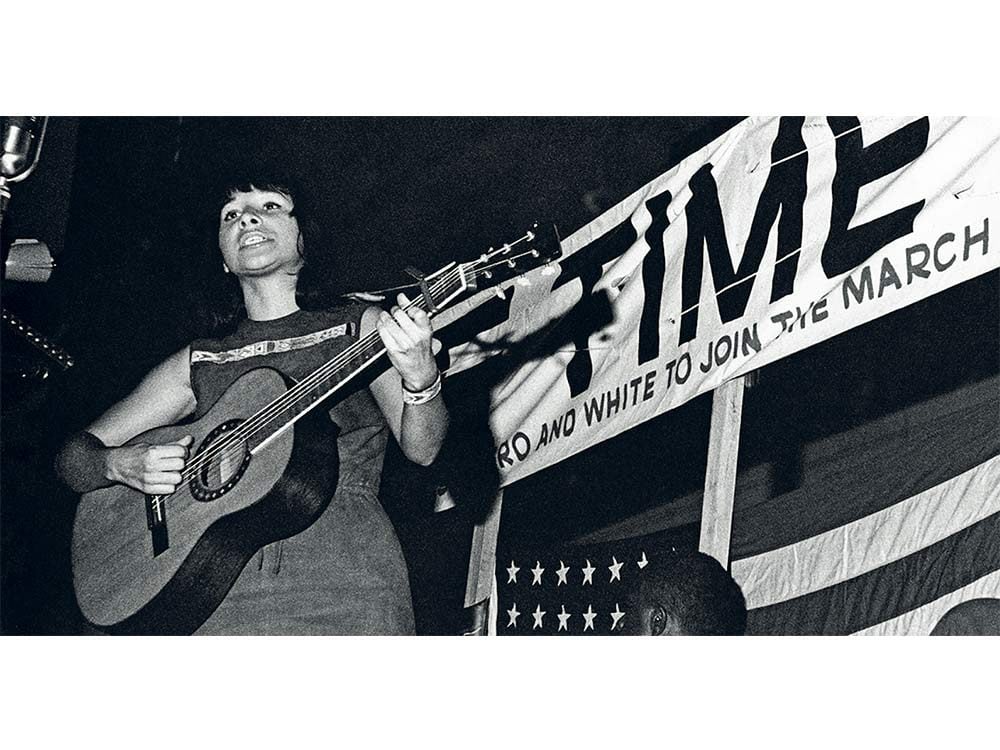

In the end, she moved to New York City, where she began performing in Greenwich Village, playing original material. Songs like “Cod’ine,” about developing an addiction to codeine while she recovered from a throat infection; “Universal Soldier,” a pacifist anthem inspired by injured American soldiers returning from the Vietnam War; and “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” a critique of the American government’s decision to build the Kinzua Dam, which flooded the Seneca reserve territory between 1961 and 1966. It was important—essential—to Sainte-Marie that each song carry a message.

“The job of a poet is to get information across in a way that’s effective in making change,” she says more than 50 years later. “My songs try to offer information that has been hidden or not thoroughly discussed. I learned to write songs that were bulletproof. I can back them up with facts.”

She soon realized that the people she was performing for in Canada and the United States had little, if any, knowledge of Indigenous people—or of their own country’s history.

Instead of waiting for school boards, government or the media to fill in the gaps, Sainte-Marie decided to do it herself.

“I wasn’t trying to give them Indian 101 in an enema,” she says with a laugh. “I was giving people the information because I truly believed that if they knew, they would try to help.”

Her lessons weren’t easy to take. She was one of the first public figures to refer to the treatment of Indigenous people by Canada and the U.S. as “genocide,” a term that appeared in her 1966 song “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying.”

“When I used the word ‘genocide,’” she says, “that was not done. ‘She must be wrong,’ they said. ‘She’s just an Indian racist. She doesn’t know any better.’ But I’d get out the letters after my name, my college degrees, and say, ‘You know what? Here are the references.’”

Check out these Canadian heroes, including Cree code talker Charles “Checker” Marvin Tomkins.

Will Canada Catch Up to Buffy Sainte-Marie?

Even with Sainte-Marie’s bibliographic footnotes, it took five decades for Canada to catch up. It wasn’t until the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its landmark report in 2015 that the mainstream media began using the word “genocide” to describe the country’s treatment of Indigenous peoples. The current widespread use of the term is a testament to the power of education and the change it can inspire.

Back in the ’60s and ’70s, however, that change wasn’t seen as positive. In fact, Sainte-Marie’s attempts to edify the public were viewed as a national threat in the U.S., and both Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon allegedly ordered radio stations to keep Sainte-Marie and her music off the air.

She kept recording albums, even if, in her words, “nobody heard them.”

With the adults off limits, Sainte-Marie turned her attention to kids. During her forced hiatus from radio, she became a mother and moved into television, spending five years on Sesame Street. It was there that she taught children about Indigenous issues and, in one memorable 1977 episode, breastfeeding, by explaining the process to Big Bird as she nursed her son, Cody.

That was a revolutionary moment for many people, including Palmater. “By breastfeeding on Sesame Street at a time when few did that in public, she showed us all that mothering is a form of strength and the foundation of our nations,” Palmater says.

Not even a blacklist could convince Sainte-Marie to play by the rules. “It didn’t get me down at all because I was moving on in other directions those folks had no idea even existed.”

Going off her early folk songs, few could have guessed which course she’d chart next. On her 1969 album, Illuminations, Sainte-Marie used early synthesizers to alter her vocals and merge sounds in ways that still feel fresh today and that laid the groundwork for modern electronic music.

From there, it was down the technological rabbit hole. In 1984, Sainte-Marie got her first Apple Macintosh computer, allowing for more innovation. Not only could she take work everywhere (she claims that her 1992 album, Coincidence and Likely Stories, was the first to be sent out digitally over the Internet), she also discovered a way to use computers to produce visual art, becoming one of the first artists to display large-scale digital paintings in museums (such as the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum in Santa Fe, N.M.).

This isn’t to say that Sainte-Marie was sequestered behind a screen. Some of her most important contributions have been outside the arts. When “Universal Soldier” became the theme song of student activism in the ’60s, Sainte-Marie was on the reserves. “I was learning, teaching, spotlighting issues and spending time,” she says. “That was a base that wasn’t being covered. That’s the kind of person I am: I like to cover the base that isn’t being covered.”

Indigenous students often fell through the cracks of mainstream philanthropy, says Sainte-Marie, so in 1969 she launched the Nihewan Foundation, eventually developing curriculum aimed at establishing healthy self-esteem and identity in Native youth. This formed the base for the Cradleboard Teaching Project, which was created to provide Indigenous perspectives on history, geography and science and has included everything from material on residential schools to digital networking between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. It is necessary and timely work that has been equally vital to Sainte-Marie herself.

“The sweetest thing that has ever happened to me isn’t my Academy Award or anything like that. It’s that the foundation turned into something much bigger. Two of my earliest scholarship recipients became the presidents of tribal colleges. One of them founded the Tribal College Movement and the American Indian Higher Education Consortium,” she says. “Sometimes you can do a little thing that’ll make a huge difference. Somebody else will maximize it and turn it into something you never could have imagined.”

Listening to Sainte-Marie, you can understand why Johnson and Nixon were afraid of her. She’s that rare teacher who makes you want to learn, who makes you remember how important it is to ask questions. After all, it’s her own curiosity that has propelled her relentlessly ahead of any time she’s found herself in.

These days, though, Sainte-Marie feels like society is catching up. That’s why she’s releasing a new album this fall: Medicine Songs, a collection of old and new protest tracks. “I’m hoping it will encourage others,” she says. “I’m banging in the kitchen and I’m cooking something that gives people an appetite. They choose their menu, and then, nourished, they go out into the world and do something with that energy that no one can predict.”

It seems funny that someone who has, in a sense, foretold cultural trends for decades is saying she can’t divine what’s to come. Still, one doesn’t need to know Sainte-Marie well to recognize that she’s hopeful. Her greatest gift may be that for half a century, she’s believed in all of us, that although we repeat many mistakes, eventually we will get better. We will create. We will teach. And we will keep learning.

Next, learn more about Mohawk actor Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs.