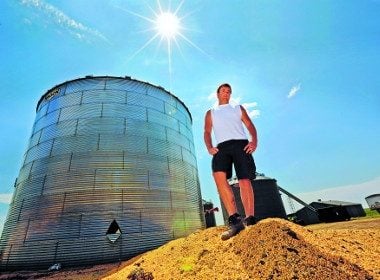

The enormous grain bins that dot the Iowa landscape store enough dried corn to swallow a body completely, squeezing the breath and life from a person in seconds. Accidents happen, and they’re often fatal. In 2010 alone, 26 Americans were killed in silo accidents. For the firefighters of Iowa, more often than not, a trip to a grain bin isn’t a rescue operation-it’s a recovery mission.

On a Wednesday last June, however, 23-year-old Baker wasn’t thinking about the risks. With his dad, Rick, getting older and the only other farmhand over 70, Baker was increasingly responsible for the family farm’s most unpleasant tasks. His first time cleaning out a dusty silo had taken all Monday and Tuesday, and now he was just trying to finish the job.

That morning, while his father and another driver, 71-year-old Kay Palmer, took turns hauling away truckloads of grain, Baker stood in the 60,000-bushel bin using a length of PVC pipe to try to break up the chunks of rotten corn that were blocking the flow. It was a sweltering day, and it was 58°C inside the massive cylinder of corrugated steel. Baker is asthmatic, so his dad had given him a battery-powered ventilation mask with a visor and a cloth that he tied under his chin. It didn’t make oxygen, but at least it filtered out all the dust kicked up while working ankle-deep in the corn.

Around 10:30 that morning, Baker’s dad left his spot on the roof, where he’d been keeping an eye on his son, to turn off the auger, the rotating screw-like device churning at the base of the silo, moving the kernels of corn out of the bin and into the waiting truck. With the load complete, Baker’s father drove off. Just seconds later, Baker felt the corn beneath his feet give way.

He didn’t know it then, but he had broken through a chunk of rotten corn that had solidified into a bridge with a cavernous air pocket beneath it. That pocket was now filling up fast, drawing in the corn-and Baker along with it-until it was up to his knees, then his waist. He had a rope wrapped around his right arm, and he held on as tightly as he could, but it was useless. The corn was like quicksand, dragging him down, and he could only watch as the cord slipped out of his gloved hands. “Dad!” Baker yelled once. He took a deep breath. Darkness, silence. He was down in the corn.

Baker was stuck firm, his left arm pointed straight up, with just his fingertips poking out of the corn. The pressure on his body was enormous. It was an awful sensation, to feel himself pressed with equal force across every inch of his body. It was like being strangled by a thousand boa constrictors. He tried to move his leg a couple of centimetres, but the corn would rush back in to fill the void, packing him in even tighter. Every breath was exhausting. He was hyperventilating, which didn’t help, either. Still, he was breathing. His mask seemed to be doing just enough. But how long could the batteries last? Three hours? Then what?

My father must know by now I’m here, Baker reasoned. Surely he’d figure it out. But a thought kept gnawing at him: what if Palmer came back and turned on the auger? The gearbox was just centimetres from Baker’s extended right foot. He’d be sucked into the machinery.

Hours crept by, and Baker kept himself from going crazy by thinking about everything he would miss. Just the weekend before, Baker and his friends had driven out to Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri. They’d rented a pontoon and gone over to Party Cove. It was one of the best weekends of his life. And to think that now it could all be over. He’d never again get to talk to his friends, some of whom had moved away from Iowa and would learn about his death over Facebook. He’d never find out what could have happened with that girl he’d just started chatting with-the girl who, at the very moment he was slowly suffocating alone, was texting him, “Did you die, mister, or are you just not talking with me today?”

Filling his lungs seemed to take more strength than Baker could muster, the slightest swelling of his chest meeting the unyielding resistance of the mountain of corn pushing in from all around him. He was tired of fighting, and began drifting in and out of consciousness.

At 10:32 that morning, just moments after driving away, Baker’s father left his son a phone message: “Hey, Arick. Like a jackass, I forgot to wait to make sure you got out okay. Give me a call when you get this.” Two hours later, when he still hadn’t received a reply, Baker’s dad called Palmer and told him to check on his son before restarting the auger. When the driver looked inside the silo, there was no sign of Baker, just his rope dangling limply from the top of the bin down into the corn. That’s when Palmer flagged down a passing state patrolman.

It was 12:45 when the Iowa Falls Volunteer Fire Department reached the farm. Fifteen-year veteran Tyler Prochaska and another firefighter, Jason Barrick, immediately lowered themselves into the bin. It was still. Silent. They scuffed through the stiflingly hot, gloomily lit structure for a few minutes before radioing back the bad news: “If the kid’s in here, he must be dead, because I don’t see him or hear him.”

Then, from down in the corn directly beneath their feet, a yell: “I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive!”

Prochaska and Barrick sank to their knees and began digging like dogs. They could hear Baker down beneath them, counting out loud for some reason, and they followed the sound of his voice. Prochaska was elbow-deep before he found the young farmer’s outstretched hand.

“Finally,” Prochaska would say later, “I grabbed something that grabbed me back.” Knowing that Baker was still alive galvanized the firefighters, who piled into the bin to help. The digging, however, was slow, and Baker’s initial euphoria at being discovered began to fade. With his head peeking out of the corn, it was clear that he was at the centre of a funnel, the grain piled high and precariously around him. Five times, Prochaska and Barrick uncovered Baker’s head, and five times something shifted and the grain avalanched down onto him, plunging him back into the terrifying darkness. They dug again, working to the sound of the intermittent beeping coming from Baker’s mask as the batteries died.

The firefighters brought in the grain-bin rescue tube-a metal cylinder with detachable panels designed to contain the victim and relieve some of the pressure. Only recently purchased, it had yet to be tested. Prochaska and Barrick pushed sections of the tube down into the corn around Baker, forming a barrier, then climbed in with him, taking turns scooping out the grain with their hands, helmets and whatever else they could use.

Prochaska wedged himself into the tube, using his body like a jack to keep the barriers from collapsing. Even so, one of the barriers buckled, letting grain trickle in, so Prochaska jammed his back against the leak. Paramedics urged Barrick and Prochaska to take a break after working for two and a half hours in the broiling silo, but they refused to leave Baker’s side. If we move, he’s gone, Prochaska thought.

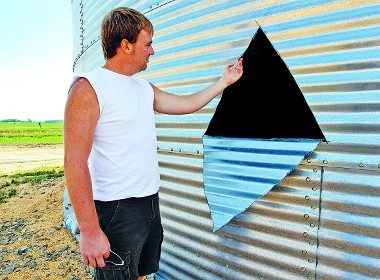

Meanwhile, more than 120 volunteer firefighters from across the county, as well as local farmers, gathered around the bin, ready to help. Using saws and torches, they cut holes into the base of the bin to try to empty the container, though the grain only trickled out. Volunteers took shifts, shovelling out the grain that pooled beneath the openings. It was slow going until Baker’s dad, who’d arrived a few hours earlier, used a neighbour’s bulldozer to clear the debris.

The rescue was in its third hour, around 4 p.m., when it happened. In one swift motion, volunteers freed Baker’s leg and pulled him up and out of the tube, alive, where he collapsed onto Prochaska. Baker sobbed as the two men hugged and then fell to the ground, too exhausted to support their own weight.

A month later, the Baker family held a dinner for the rescuers. Remarkably, Baker had recovered over two days in the hospital without lasting damage. Doctors had pumped him full of liquids and extracted corn kernels embedded in his skin. His heart had been pushed to the limit, they told him. “They said if I had been five years older, my heart would have exploded,” says Baker. “If I had been five years younger, I would have been crushed.”

At the dinner, Baker and Prochaska shared hugs and tears before diving in to pork loin and comparing notes on the ordeal. Between the toasts, Prochaska had a question: “Why were you counting out loud?” he asked Baker. “Were you timing us?” Baker laughed. “I wasn’t counting anything,” he said. “I just didn’t have anything else to say.”

For the most part, Baker has put his experience in the silo behind him, as if it were a surreal dream rather than a near-death experience-keeping the memory smooth and tidy, the edges rounded off.

Sometimes, though, a heavy feeling comes over him, and he’ll slump under pressure and an awful helplessness. For a second, he’ll be there-back in the darkness, down in the corn.