Canada’s Most Riveting Unsolved Mysteries

Can you crack these spooky disappearances, paranormal sightings and puzzling whodunits?

15 Unsolved Canadian Mysteries

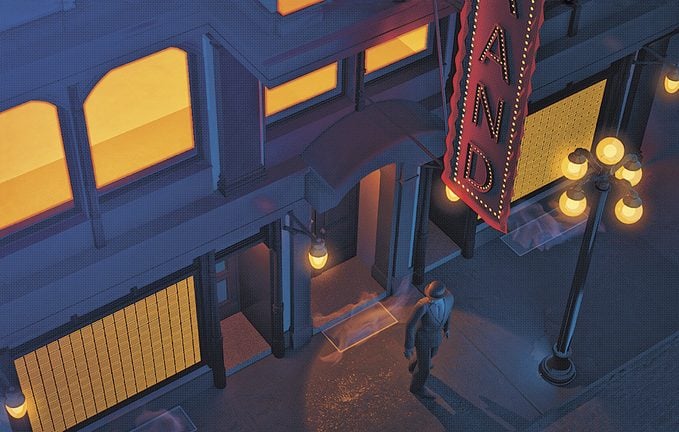

The Missing Theatre Magnate

On December 1, 1919, Ambrose Small, a Toronto theatre owner, sold the bulk of his empire to a Montreal company for $1.7 million. The sale itself was not suspicious: given the growing popularity of moving pictures, Small had decided to divest himself before it was too late. The next day, he and his wife, Theresa, together deposited the money. On the street they parted ways, Small promising to be home by dinner. But he never arrived. Small had a reputation for carousing, and Theresa waited two weeks to report his absence.

Today, the potential killers sound like players in a murder-mystery game: wife Theresa, a fixture in Toronto society; Small’s money-grubbing sisters with no other source of income; the disgruntled secretary; and at least one mistress. There was even the possibility of a gangster hit, given Small’s substantial gambling habit.

But if suspects were plenty, the investigation was clumsy at best. “This was a different era of policing,” says Katie Daubs, author of The Missing Millionaire: The True Story of Ambrose Small and the City Obsessed with Finding Him. “At that time, police mostly patrolled the streets and successfully solved crimes by being present when they happened.”

A series of private investigators tried their luck at cracking the case. So did clairvoyants and cryptographers. Theories multiplied, and the tabloids made a meal of every false lead (including a deathbed confession from Theresa, later deemed a forgery). Ultimately, neither Small nor a culprit was ever found, and in 1960 the Toronto Police officially closed the case.

Take an in-depth look at Canada’s most notorious cold cases.

The Empty Money Pit

In 1795, three teenagers discovered an odd hole in the ground on an island off the south shore of Nova Scotia. The area was rumoured to be a pit stop for pirates, so the boys began digging, hoping to unearth buried treasure. Instead, they struck layer after layer of buried timber. Though the trio never found any booty, they did discover a cryptic stone slate inscribed with unfamiliar symbols—a cipher that, at least in their interpretation, promised a huge payday.

Thus began the saga of the Oak Island money pit, which has beguiled countless explorers and excavators—including John Wayne and Franklin D. Roosevelt—over the past 225 years, even bankrupting some. Falls, explosions, suffocation and other accidents have claimed the lives of six men who tried to find the island’s prize. So far, explorers have spent millions on the search and found not a penny.

The Pacifist Assassination

At a little past 1 a.m. on October 28, 1924, a train travelling the Kettle Valley Railway in B.C. lit up the sky with a giant fireball. Nine people were killed in the explosion, including the presumed assassination target, Peter Verigin, spiritual leader of the Doukhobor people, a Russian religious sect. Since immigrating to Canada at the turn of the century, the group had faced resentment for their strict pacifism and communist ideals. There was an outcry when the government granted the Doukhobors a religious exemption from World War I.

By the time of his death, Verigin had built an extensive list of enemies. Potential suspects included a Doukhobor splinter group, the federal government, the American Ku Klux Klan and even Verigin’s own son, Peter II, who assumed his father’s leadership role. Despite a $2,000 reward, no charges were ever laid, and questions remain to this day, including whether it was an assassination at all. It’s true that Verigin was a contentious character, but some experts believe a leaky gas line or hastily packed dynamite in the suitcase of a local miner may have been responsible for the kaplow!

Here are 10 true crime movies that will chill you to the bone.

The Year of the UFO

1967 was a bumper year for unsolved Canadian mysteries. During the centenary of Confederation, the country was visited by multiple UFOs—or so people claimed. The convincing sightings prompted investigations by intelligence agencies and discussions in the House of Commons.

Rational minds might dismiss the reports as a product of the times. Anxious about the Cold War and excited by the Apollo era, Canadians were gazing skyward more than ever before. “It was the perfect storm for unusual things to be reported,” says science writer Chris Rutkowski, the author of several books about UFO sightings. “Any type of intrusion—people seeing things that shouldn’t be flying in Canadian airspace—was certainly of interest.”

Here are three of that year’s most mystifying close encounters:

Falcon Lake, Manitoba – In May 1967, an amateur geologist named Stefan Michalak went prospecting in the wilderness east of Winnipeg and encountered a silver, saucer-shaped craft about 10 metres wide and four metres high, grounded in the forest. As he approached, he heard the whir of engines coming from an open door. When he touched the vessel, it burned the fingertips of his gloves and shot out a burst of compressed air, scorching his shirt, cap and skin before quickly rotating and zooming away. Michalak was initially treated for burns and, later, for recurring blackouts. The RCMP discovered a barren 15-foot circle containing radioactive soil where he reported seeing the UFO.

Kananaskis, Alberta – Out for a hike with two friends in July, journalist and novelist Warren Smith spotted a shiny disc swiftly rising and falling overhead. He took two photos before the object disappeared in the distance and then mailed them to the Department of National Defence. After both Canadian and American intelligence studied the pictures, they concluded he’d indeed seen two unidentified flying objects, about 15 metres in diameter and three metres tall. The agencies added in an official report, “If the story and photographs are a hoax, then it is a well-prepared one.”

Shag Harbour, Nova Scotia – Late one October evening, at least 11 witnesses in this tiny town—including RCMP officers, sailors and pilots flying nearby—all reported seeing a large object with four flashing lights hovering above, and then crashing into, the harbour. Upon investigation, authorities found sulphurous yellow foam on the surface of the water. But countless diving expeditions, including one as recent as 2018, have turned up no wreckage or evidence of anything unusual.

The Silent Castaway

In 1863, a young boy stumbled upon a legless man in his 20s on the beach of Sandy Cove, Nova Scotia, and ran home to get help. Asked to share his identity, the mystery castaway grumbled something that sounded like Jerome. The name stuck, especially in the absence of any other communication or clues about a native language.

For almost 50 years, Jerome relied on a government stipend and the goodwill of strangers, passing from house to house. He eventually settled in the village of Meteghan, where one host family reportedly charged admission to anyone who wished to come and gawk at the mysterious local legend.

If Jerome knew his own origin story, he never revealed it. Many Maritimers have theories: he was a sailor who got the boot after a failed mutiny attempt, an heir to a fortune, a prisoner of pirates or maybe (likely?) the victim of a terrible head injury. He died over 100 years ago, sharing his expiration date with the sinking of the Titanic. So far only one event inspired a movie.

The Skylight Caper

In the early hours of Labour Day 1972, three men met under the cover of darkness outside the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. They pulled black ski masks over their faces and prepared to commence the largest art heist in Canadian history.

To begin, one man climbed a tree and jumped onto the museum’s roof, where he lowered a ladder to his co-conspirators. They proceeded to a skylight that was under repair—one of the panes of glass had been replaced by a plastic sheet—and slid down a 15-metre rope into the gallery.

Once inside, the thieves overpowered three night guards and left them bound and gagged in the museum’s lecture hall. They then stalked the halls in search of their loot: 18 canvases, including Rembrandt’s Landscape With Cottages (worth roughly $20 million today) and 39 pieces of jewellery, including an 18th-century gold watch.

The robbers were in and out within 30 minutes, but the search for the pieces they pilfered continues to this day. Two items—a pendant and a Brueghel painting—were ransomed to police in the months following the heist, but the rest remain at large, as do the burglars. No suspects were named, and no charges were ever laid.

The Ghost Ship of the Great Lakes

The French explorer René-Robert Cavelier has many claims to fame: he claimed the state of Louisiana for King Louis XIV, and he was one of the first Europeans to traverse the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. His most mysterious legacy, however, is Le Griffon, the ship he lost on the Great Lakes.

In 1679, Cavelier sailed Le Griffon from Niagara Falls to an island near modern-day Green Bay, Wisconsin, where he traded with its Indigenous inhabitants. Eager to explore the area, he disembarked and ordered his crew to return to Niagara with a load of furs. It was the last time Cavelier—or anyone—saw Le Griffon.

Since then, many historians have put forward their own theories to explain the ship’s disappearance: the crew made off with their wares; a local tribe captured and burned Le Griffon; or, the boat was wrecked on Manitoulin Island. None of those hypotheses have satisfied modern myth busters, and the search for Le Griffon continues.

Don’t miss these haunting tales of Canada’s most famous shipwrecks.

The Redpath Mansion Murders

In June 1901, gunshots rang out from behind the doors of Redpath Manor, home to Montreal’s famous family of sugar barons. Minutes later, the blood-soaked bodies of Ada Maria, 59, and her 26-year-old son, Clifford, were discovered by her other son, Peter. The coroner and a family physician determined that Clifford accidentally fired during a seizure and then turned the gun on himself. The official account is plausible, if it’s true that Clifford had epilepsy—no record of him having the condition exists prior to this event.

Over a century later, mystery shrouds the two Redpath family deaths. Police were never called, and both bodies were buried within 48 hours. Rumours spread about other potential suspects, including Ada Maria’s daughter, Amy, who likely stood to inherit a chunk of the family fortune. Today, researchers suspect the coroner’s account was devised to protect the wealthy family’s privacy, not reveal the truth.

The Toonie Truck Heist

The Canadian two-dollar coin debuted in February 1996. Five months later, three million dollars’ worth of the newly minted currency was stolen from CN’s Turcot Yard in Montreal. The biggest coin theft in Canadian history ran smoothly (and in broad daylight!) as thieves drove a truck containing 1.5 million toonies out an emergency exit. The abandoned vehicle was later located, but the money was gone. Authorities would not say whether it was an inside job. There were many similar trucks on the lot that day, which, along with the fact that the coins were unmarked, made apprehending the guilty party or parties unlikely. Still, Montreal’s police chief put out a nationwide alert for anyone making major purchases with a whole lot of pocket change.

The Vanished Village

On a frigid November day in 1930, a fur trapper named Joe Labelle arrived at a tiny town on the shore of Anjikuni Lake, in modern-day Nunavut. Having visited before, Labelle knew the village to be a lively community of tents and huts—a great place to trade or spend the night. Except on this particular day, the settlement was deserted.

As Labelle tiptoed through the vacant village, he noticed strange signs. A meal had been abandoned in mid-preparation. Food, clothes and weapons had all been left behind. Most disturbingly, several sled dogs had starved to death and were lying beside graves that had been emptied.

An RCMP investigation concluded that the approximately 30 Inuit inhabitants had departed eight weeks before Labelle arrived. Officers had no idea where the Inuit went or what happened to them. Some theories blame a Wendigo—an antlered, human-eating monster—rumoured to lurk nearby, while others entertain the idea of an alien abduction. Meanwhile, skeptics suggest this unsolved Canadian mystery is a hoax, arguing that the first official record of the event—an article in a Manitoba newspaper—was an early example of “fake news,” burnished by decades of retelling.

The Ill-fated Lovers

In August 1993, Kimberley Lockyer, 29, and Dale Worthman, 30, vanished. The young couple told no one where they went, because by every indication they intended to return. Their car was still parked outside their basement apartment in Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s, Newfoundland. Inside, fresh bread sat in the toaster and the fridge was fully stocked. They’d left behind wallets, IDs and cash.

Police interviewed friends, family, taxi companies and airlines, but no one knew a thing. Tips trickled in from the public, but they were dead ends, too. Years passed, and the case grew cold. If Lockyer and Worthman were alive, they were gone.

Then, in July 2006, Worthman’s friend, Joey Oliver, went to the police. Racked by a guilty conscience, he claimed he had lured the couple into the woods outside St. John’s that long-ago summer at the behest of his accomplice, Shannon Murrin. Oliver believed that Murrin simply wanted to shake Worthman down for a drug debt, but the situation took a grim turn: according to Oliver, Murrin shot both Worthman and Lockyer.

Following Oliver’s directions, police found two bodies in a single grave. Oliver pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to 15 years, but maintained he wasn’t the killer. While the Crown believed he hadn’t pulled the trigger, it couldn’t corroborate his claim that Murrin did. For his part, Murrin denied any involvement in the killings. He insisted that Oliver tried to frame him because he was an easy target—he had been previously charged, but acquitted, of another murder.

So who really killed Dale Worthman and Kimberley Lockyer? Unless one of these men changes their story, we may never know.

The Wrecked Plane

In 1959, John Diefenbaker, citing high costs, axed development of the Avro Arrow jet, even destroying prototypes and blueprints. In 2011, an intact Arrow ejection seat was discovered in the U.K., reigniting rumours that one plane survived and was smuggled out.

The Outlaw’s Gold

There are persistent rumours that the American outlaw Jesse James fled to Ontario after robbing a Wells Fargo train in 1870, assumed a fake identity and buried his loot in the hills of the small township named Mulmur. Despite much searching, however, no treasure has ever been found.

The Artist Whodunit

Tom Thomson was last seen alive on July 8, 1917, as he set off to fish Canoe Lake in Algonquin Provincial Park. His body surfaced over a week later, with a bruise on his head and fishing line wrapped around his ankle. Nobody knows whether it was an accident, suicide or murder.

The Confederation Assassination

Father of Confederation Thomas D’Arcy McGee was shot dead on April 7, 1868. The presumed assassin, Patrick James Whelan, was later hanged but maintained his innocence, saying he knew who pulled the trigger but didn’t want to go down as a snitch.

For more unsolved Canadian mysteries, check out 10 of Canada’s most haunted places.