“Like all of Rosenberg’s lies, the story sounded just plausible enough…”

Looking back, it does seem unlikely that a Swiss billionaire baron would be seeking love on the Internet, but when Antoinette met Albert Rosenberg on eHarmony in February 2012, she figured she got lucky. Along with the European title, he was charming and, yes, mega-rich, overseeing a Canadian merchant bank called Marwa Holdings Inc. He was also heir to the Ovaltine fortune, a direct descendant of Albert Wander, who invented the popular Swiss malt drink back in 1904. This was how he supported his lavish lifestyle. Or so he said.

Antoinette was in her 50s and living in Toronto when she met Rosenberg (she requested that we not reveal her last name). Her new boyfriend lived in a penthouse apartment in the swanky Yorkville neighbourhood. On a getaway to Montreal they stayed at the Ritz-Carlton. There would be future trips, he promised, to his home in the south of France, and adventures on his yacht, which he said was moored in Monaco. After dating for just a few months, they moved in together. Rosenberg convinced Antoinette to quit her job and sell her home. He told her that he would invest the profits from that sale in his company. Antoinette handed over $155,000—a lot of money for her. He drew up a contract and said he would make her a director of Marwa, which loaned large sums of money at high interest rates.

They got married in March 2013, scarcely a year after they’d met. Antoinette took Rosenberg’s name. The ring was a family heirloom of such great value that Rosenberg instructed Antoinette to leave it in their safe whenever she went out. Everything in their shared home was his; on Rosenberg’s insistence, Antoinette had sold or given away most of her belongings. Her beau had a taste for luxury brands. Shopping was a daily pastime, and boutique owners greeted him by name, fawning over him from the moment he walked in. Yorkvillers knew them and would smile and wave like humble villagers paying respects to their feudal lord.

While Antoinette and Rosenberg were dating, she lost touch with a lot of her old friends. Rosenberg gave Antoinette a cellphone and used its GPS capability to track her movements. When she made calls from the house, he would stand in the background, listening. A few months into the marriage, Antoinette was looking at bank records when she noticed another name attached to the Marwa corporate documents: Mihaela Zavoianu. This stranger appeared to have signing authority on the company bank account. Rosenberg told Antoinette that Zavoianu was a former associate he was helping out. Around the same time, she brought her engagement ring in for resizing. The clerk was impressed until he pulled out his magnifying glass and saw that it was costume jewellery. When Antoinette confronted her husband, he explained how, in his grandmother’s era, it was common to have an imitation ring made for travelling. The two must have been mixed up at some point. Like all of Rosenberg’s lies, the story sounded just plausible enough, and Antoinette found it easier to believe him than to consider the alternative.

“A man with a shocking lack of conscience…”

One evening, the Rosenbergs were out for a walk. She wanted to talk about their marital issues. Rosenberg reacted with anger, grabbing her arm in a way that was violent enough to leave bruises. Soon after, Antoinette was on Skype with her daughter. Rosenberg lingered in the background. To avoid detection, Antoinette carried on a mundane conversation while her daughter held up notes onscreen. She felt her mother wasn’t safe and encouraged her to go to the police. On August 12, Antoinette met with detectives at 53 Division and told them about her husband’s physical and emotional abuse. She also said she had suspicions about his finances.

Albert Allan Rosenberg will often change the details of his history, but his standard version is this: he was born in Cairo while his father, Alvin, a Canadian international lawyer, was stationed there in the early ’40s. His mother, Marcelle, grew up in Switzerland, where she met Alvin. The family returned to Switzerland before Rosenberg was a year old, and he was raised in a town called Küsnacht.

By the mid-’60s, the Rosenberg family had relocated to Canada. Rosenberg claims he studied computer science at the University of Toronto and got an MBA from Harvard, but U of T didn’t have an undergraduate computer science program until the ’70s, and Harvard has no record of him ever attending. In the early ’70s, he returned to Switzerland, which is where he met and married an heir to the Ovaltine fortune. The couple had three daughters. While living in Zurich, Rosenberg says, he established a public trust with his wife’s wealthy family. On other occasions he will say the trust is over 100 years old. Conflicting details come up often in Rosenberg’s stories, which tend to mix some facts in with embellishments or blatant lies.

Rosenberg says he and his wife moved to Toronto in 1981 and opened a gallery. They accepted paintings on consignment but used the proceeds of sales to pay for car leases and racquet club memberships instead of dispatching payments to the original galleries. By 1984, Rosenberg had declared bankruptcy. In June of 1986, one of the swindled owners contacted the RCMP. Shortly afterwards, both Rosenbergs were charged with fraud totalling over $300,000. She fled to Europe with their children, while he was arrested and then released on $2,000 bail.

Awaiting trial, Rosenberg met a photography curator named Lorraine Monk. At the time, she was raising money for charity. Rosenberg offered to help her by acquiring Picasso’s Buste de Femme, 1937. They would sell it for a sizable profit—all he needed from her was $100,000. A week after writing a cheque, Monk learned that Rosenberg was bankrupt. At his trial for fraud, Monk said she had been so distraught that she had felt like she wanted to die. The prosecutor described Rosenberg as a man who “played fast and loose with the truth,” taking note of his “shocking lack of conscience.” Rosenberg received a four-year sentence—his first of many prison terms.

When released on parole, he returned to his usual tricks, this time in Halifax. He was convicted and sentenced again, then paroled in 1994. Five months later, he was busted yet again on fraud charges and sentenced to two years. When he got out, he started a relationship with a woman named Birgitta Baldes, a bombshell with the purring accent and fashion sense of a Gabor sister. They flew to Switzerland together. There, they rented a blue Porsche Boxster and a deluxe edition VW Golf and relocated to Aix-en-Provence, France, where Rosenberg posed as a Swiss-American tycoon (his latest persona). The couple dressed in flashy outfits: he favoured black leather pants and a long yellow scarf; she, jewels and fur. He told people that he was in the small French town because the area was ripe for a buying spree.

A global network of scammers is targeting older people. Here’s how to avoid becoming a victim.

“Rosenberg had a way of making the people in his orbit feel special, smart, important…”

Canadian journalist Nicholas Steed happened to live in Aix-en-Provence when Rosenberg and Baldes came to town. Steed says they were so entertaining that he overlooked certain red flags. In a piece he wrote for the National Post in December 1999, Steed described Rosenberg as a “bit of a queer fish, but fun to be with, even magnetic, his often crude boasting tinged with a mischievous sense of humour.” He recalls visiting the couple at their opulent rental property. Rosenberg was eager to show off his art collection, which included canvases by Francis Bacon and Mark Rothko. At one point Steed asked Rosenberg whether, given that he owned a Bacon, he might also own a Freud, referring to Lucian Freud. Rosenberg was confused. “What do you mean? Sigmund?” he asked, betraying ignorance that would be inexcusable in an undergrad art student, never mind a worldly collector. Like the pricey real estate, art was a way for Rosenberg to establish credibility—a prop in his elaborate masquerade.

Later it would come out that he had purchased the paintings from the prestigious Marlborough Gallery in New York. He had written them a post-dated cheque for $4.3 million, asking that they wait a few days before cashing it, as funds had to be transferred from Liechtenstein. The gallery had shipped the artwork immediately. Rosenberg then tried to sell the paintings to Christie’s auction house. They weren’t interested, perhaps because he didn’t have proper ownership documents. Next he approached Sotheby’s in New York, which did buy the works, giving Rosenberg a $700,000 deposit. By this point he had moved. A private detective hired by the Marlborough Gallery tracked Rosenberg and Baldes to Florence, where, in October 1999, he was establishing his latest identity as a wealthy buyer of antiques.

Rosenberg and Baldes were arrested in Italy at the request of the French police. She was rapidly released, while he spent 55 days in jail, and was eventually let out on a technicality (the French paperwork was late). They returned to France, where they were rearrested in 2000. Rosenberg was convicted of fraud, but he was soon back in Canada. Over the next decade, he landed in jail several more times. Each time he got out, he would infiltrate a new circle, earn trust, steal money and get busted again.

In 2011, Rosenberg self-published a book titled Taking Stock in Your Future. Some have speculated it’s largely plagiarized; many sections appear to be lifted from Outperforming the Market by the Ottawa-based business writer Larry MacDonald. Rosenberg would use his book to impress his marks. He could often be found dining on the patios of Yorkville cafés with it placed conspicuously on his table, his Louis Vuitton cellphone case close by. The ability to feign financial expertise was essential to convincing investors to sign over hundreds of thousands of dollars. One such investor, who agreed to speak to me on the condition of anonymity, is a Toronto businessman in his mid-50s I’ll call James. He met Rosenberg through a colleague. Introductions via a respectable, trustworthy third party are among the most established moves in the swindler’s playbook. If Rosenberg met a successful businessman, he would ask to be introduced to his lawyer; if he met that lawyer, he’d ask for an introduction to his most successful client, and so on.

Rosenberg had a way of making the people in his orbit feel special, smart, important. “He had the bearing of a cultured individual; I never really questioned it,” says James, who dined with Rosenberg at Café Boulud. It wasn’t until the third time they got together, in January of 2013, that Rosenberg mentioned the possibility of an investment. It came up in a casual way, as if it had just occurred to him that he might be able to help this new friend make a quick buck. Later that month, James wrote a cheque for $300,000. He never told his business partners about the investment and spent months chasing Rosenberg for repayment.

“His small, dark eyes were more desperate than steely…”

In 2009, Rosenberg met a Toronto woman named Mihaela Zavoianu online. In 2010, the relationship stalled when Rosenberg went to prison. Once he got out, the romance continued. Zavoianu moved into his penthouse and signed over $80,000—her life savings—to the man she planned to marry. But in the winter of 2012, Rosenberg told Zavoianu she would have to move out for a while. His daughter, he explained, was severely depressed and coming to live with him. In fact, he had just met Antoinette.

After Antoinette went to the police, Rosenberg’s stories started to unravel. She handed all their personal financial documents over to the authorities, who called in fraud officers to investigate. The police interviewed his victims, many of whom were educated, high-earning men. The cops charged Rosenberg with assault and eight counts of fraud, totalling $1.2 million. He pleaded guilty to all charges. After his arrest, Antoinette didn’t have enough money to rent even a modest apartment, so her family is providing a place for her to live. Rosenberg was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment.

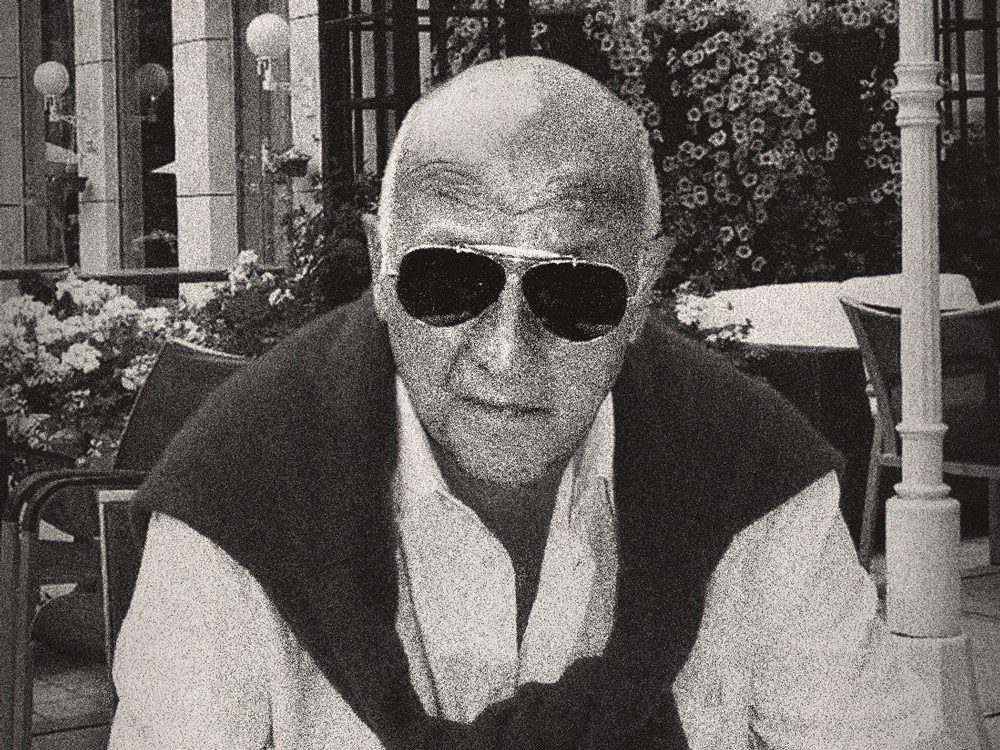

In September 2014, I visited Rosenberg at the Beaver Creek Institution in Gravenhurst, Ont. After passing a security check, I immediately spotted him waiting behind a glass door. He wore aviator shades and stood a commanding six foot something, dressed in prison-issue jeans and a long-sleeved blue work shirt. From a distance he looked menacing, like a Bond villain. Close up and without his sunglasses, his small, dark eyes were more desperate than steely. Unkempt tufts of grey hair grew out of his pointy ears. Rosenberg was soft-spoken and, at least on the surface, genteel.

Beaver Creek seems like a tolerable place to do time. Every day Rosenberg gets up at 5:30. It is, he explained, “force of habit after years as a successful businessman.” In the morning, he tutors inmates who are working toward their high school diplomas. Afternoon time is discretionary. Rosenberg visits the library, where the book selection is, he said, “actually not that bad.” Inmates cook their own meals. Some of them do so in groups, but Rosenberg keeps to himself. To stay sharp, he reads up on the great minds. Recently he’d been studying Kierkegaard.

Much of his story about his past didn’t line up with information I had researched. Sometimes it didn’t even match up with itself. “What year were you born?” I asked at the beginning of our chat. “Nineteen forty-two,” he responded. “How old are you?” I asked about an hour later. He answered 69. Lies are Rosenberg’s default response, which makes it almost impossible to know anything about him with certainty. At the library, I had found a piece in the Toronto Daily Star about a young man named Albert Rosenberg who had won a prestigious student award. The accompanying image was fuzzy, but I recognized what looked to me to be those same pointy ears. The piece was printed in 1946, which would put Rosenberg well into his 80s. “Is this you?” I asked him, holding out the photocopied story. He said it was.

Many of Rosenberg’s victims say they knew something was off, but what are you going to do, ask a man how he can be 69, 72 and 80-plus at the same time? For every accusation, Rosenberg had an explanation. It was all a misunderstanding, he said. He had always intended to pay his investors back and still planned to make restitutions as soon as he was “liberated.” There was much talk of the trust, which Rosenberg said was still in existence and worth millions. The police say they have found no evidence of it, that it’s as real as the summer home in the south of France or that yacht moored in Monaco.

Rosenberg will be up for parole in a few years. He said he planned to rebuild his life and he won’t be making any attempts to defraud anyone. “It has to stop. I keep winding up here,” he said. During my last visit, Rosenberg asked if I had received the Kierkegaard text he’d sent me. I had, though what he called an excerpt was more of a Wikipedia-style overview. All the same, it was telling, considering the history of the person who had sent it to me. Truth, Kierkegaard argued, is subjective.

Meet the investigators and scientists fighting food fraud in Europe.

© 2014 By Courtney Shea. Toronto Life (January 2015). Torontolife.com