This Photographer Captures Life in the Congo’s Displaced Persons Camps

Today, everybody’s a photographer. Millions of images are uploaded to the Internet each day, mainly to Facebook and Instagram. We have pretty sunsets, staged food and smiling selfies to last an eternity. “Great photo!” friends enthuse online.

But a great photo is more than just a captured moment. As Roger LeMoyne’s work shows us, a great photo serves as a portal to another time and place, opening eyes and hearts by sensitively bearing witness. It speaks of, and to, the world.

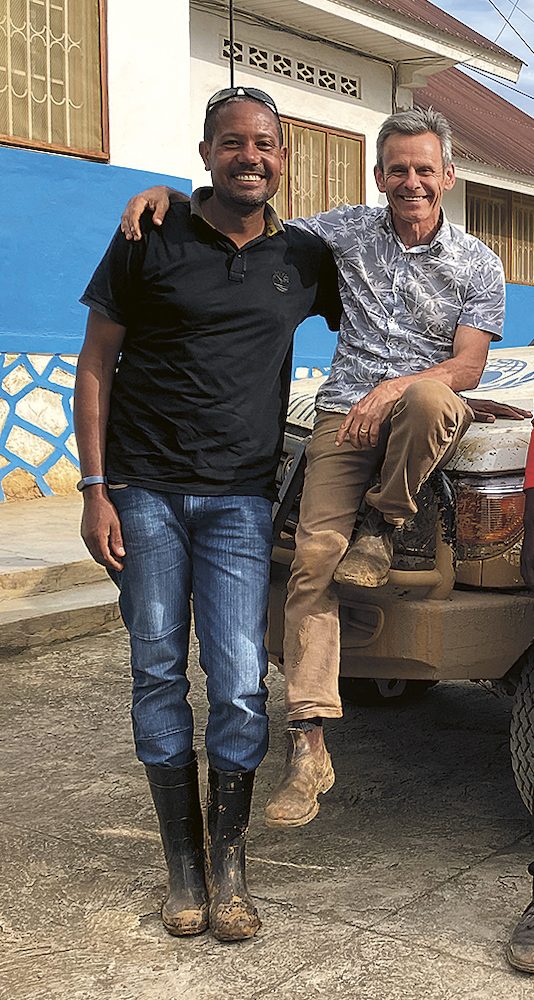

LeMoyne is a 66-year-old Montrealer. He studied cinema at Concordia University and, in 1985, took a self-financed trip to Papua New Guinea. He sold photos from that trip to Destination, a travel magazine of the day. A few years later, in Manhattan, he walked into a UNICEF office on a whim. There, his portfolio earned him his first commission, to shoot in Niger. He has since worked in 40-odd countries, recording poverty, migration and human-rights abuses.

Last fall, UNICEF sent LeMoyne to document the humanitarian crisis in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DRC is the second-largest country in Africa, and its eastern provinces are home to a vast catastrophe. Ethnic hatred, resource disputes and lack of lawful governance have led to the slaughter of untold thousands of innocents and the displacement of 4.68 million as of last November.

The intimate empathy of LeMoyne’s photos makes it easy to forget that he begins each assignment as a stranger to his subjects. Does he have a special gift for self-effacement, a chameleon-like way of blending in?

“The people in these photos can’t isolate themselves with walls and doors, the way people in the West do,” he says. “In a refugee camp, lives are more porous, more open. And people in extreme poverty have bigger things to worry about than a guy with a camera.”

At day’s end, LeMoyne returns to a guest house and dinner. He’s keenly aware of his own good fortune, but other emotions complicate his gratitude: frustration, anger, humility and awe in the face of the human capacity to endure.

“The world’s inequality wasn’t lost on me as a young person,” he says, “but with all our advances, it’s stunning that we still haven’t addressed the core issues—nutrition, security, clean water. It staggers the mind that during the three decades since I started this work, the world has become not a better place, but an even more unfair one.”

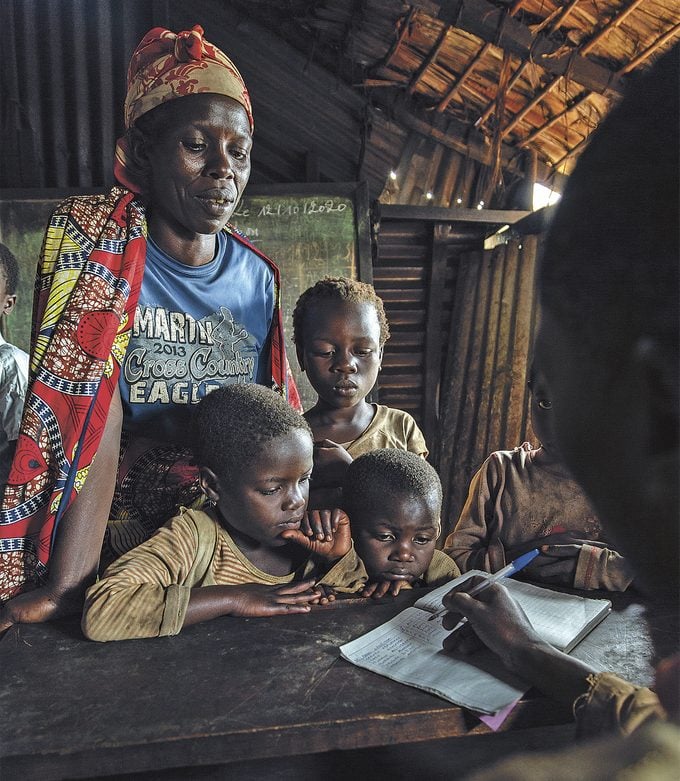

A mother registering her children for school in a camp in Mweso.

A Congolese soldier pushes a motorbike laden with produce.

A boy carrying firewood for cooking fires.

Roger LeMoyne (right) with his UNICEF driver, Michel Uyterrhaegen.

Children greeting visitors in a camp in Bunia, Ituri Province.

A view of a camp on the outskirts of Fataki, Ituri Province.

Nurse Ange Amani provides a lesson on nutrition at a health station run by UNICEF NGO partner Heal Africa in Kizimba, North Kivu.

Thousands of people live at a church in Drodro, using it as a sanctuary from the violence that has driven them from their villages.

Five-year-old Sifa Havugimana waits for her turn to be monitored for malnutrition.

A youth adjusts his COVID-19 mask in front of murals depicting demobilization of children associated with armed groups.

Next, read up on the organization that’s connecting teens worldwide to effect positive change.