The Paratrooper

By Shelley Youngblut

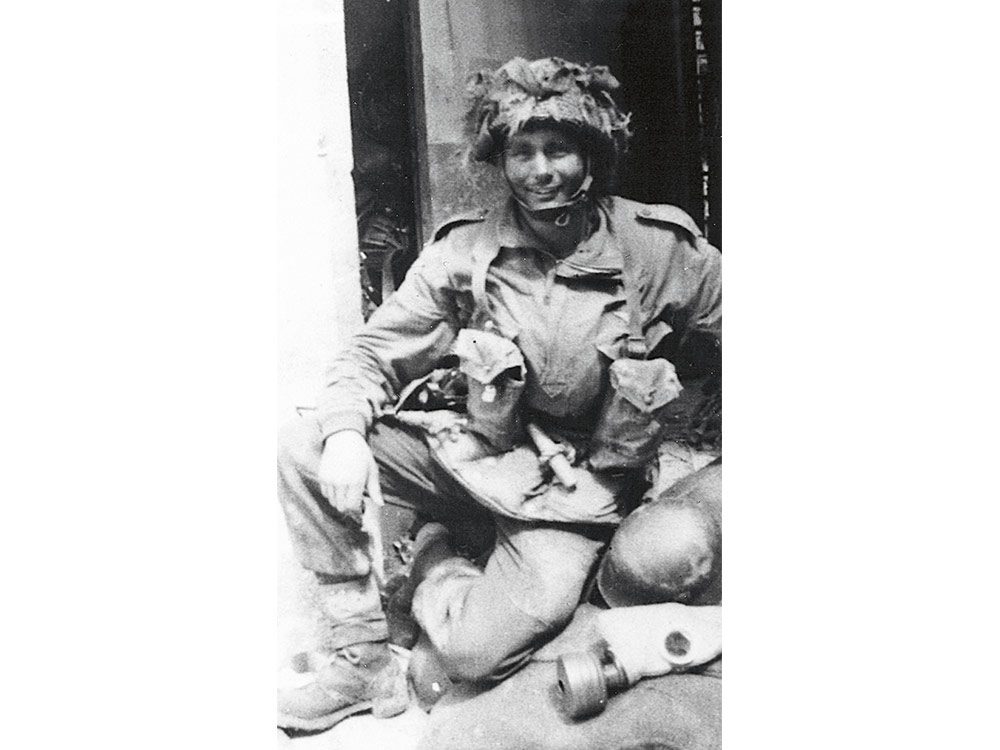

Flying over the English Channel toward Normandy, clouds breaking up the moonlight, Cpl. John Ross knew three things. He knew he was going to drop into occupied France five hours ahead of the D-Day beach invasion. He knew his advance team was expected to destroy a bridge and clear out an enemy garrison at the village of Varaville in order to slow the German counterattack when the rest of the Allied Forces landed by sea and air. He also knew that, while someone was bound to get killed or hurt, it wasn’t going to be him.

Before volunteering for the First Canadian Parachute Battalion in 1942, the 23-year-old had joined the New Brunswick Rangers. He was soon posted to Goose Bay, Labrador, where rangers slept throughout the winter in huts made from scraps of lumber with oil drums for wood stoves and tomato cans for chimneys. Ross had been toughened by the cold. And now, after nearly a year of extensive training in England, he was crammed inside the tiny hold of the Albemarle bomber with nine other paratroopers, preparing to jump.

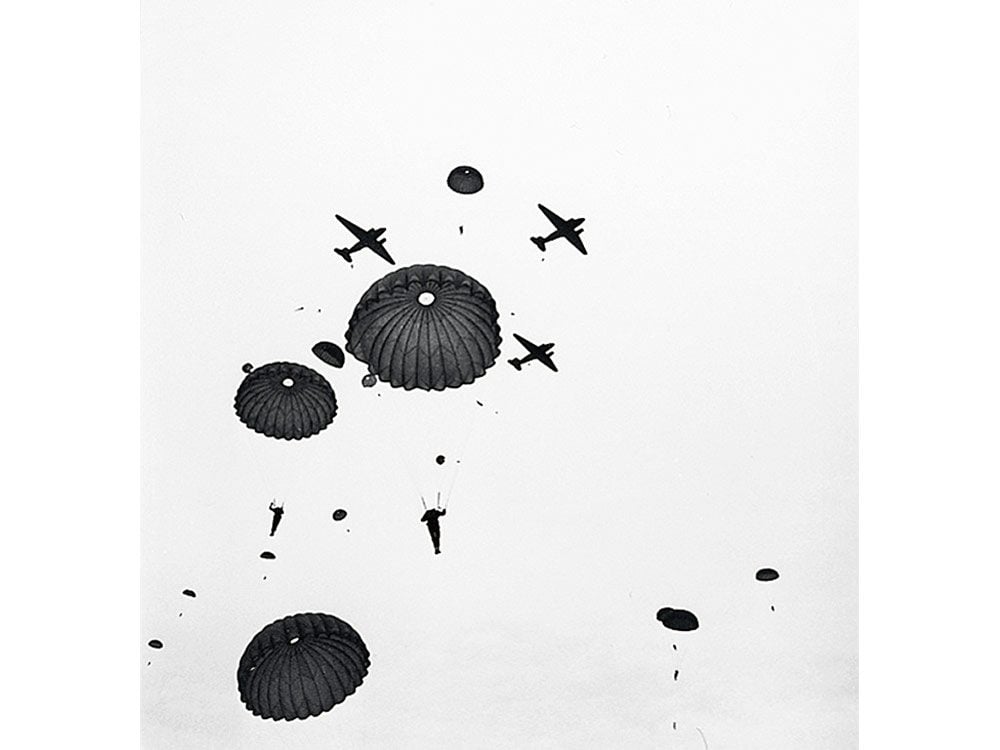

Ross looked at his watch. It was 12:15 a.m. on June 6. The aircraft—one of 12 carrying C Company of the First Canadian Parachute Battalion—managed to hold steady while other planes zigzagged to evade explosive shells fired from German anti-aircraft batteries. Two men raised and secured the sides of the trap door, leaving a hole in the floor the size of a bathtub. Ross was fourth in line. He scrambled to the opening on his hands and knees and followed his nose down into the darkness. “The planes were supposed to slow down but didn’t because the Germans were shooting at us,” says Ross. “We dropped at 600 feet, barely enough time to drop our kit bags and steer with our risers.” Ross’s parachute opened with a jolt, and he floated down in silence, into the inky landscape below. Feet clenched together, knees bent, elbows tucked in, he went into a roll as he hit the ground.

“We only had pistols, rifles and a two-inch mortar.”

The landing was easier than any he had made before, soft and right on target, just metres from the pasture Ross had noted in the aerial photographs from his briefing documents. He found his kit bag, pulled out his submachine gun and radio, then scrambled over to the group, expecting to see all 120 members of C Company. He was one of only 32 paratroopers to arrive. The others were scattered all over the countryside, some dropping as far as 16 kilometres from the rendezvous point. The cloud cover had made it difficult for pilots to find their drop zones.

Boom! The ground underneath Ross bounced. Nearly 400 Allied bombers had begun to pound a major German gun position along the Normandy beaches to the west, and off-target shells were landing nearby. The hastily assembled platoon had to move. Without enough soldiers or equipment to destroy the bridges, Ross and his unit were left to execute Stage 2 of their mission: march through an orchard toward the German stronghold in Varaville and capture the Le Mesnil crossroad, a strategic ridge that gave the enemy a view of the coastline, where Allied Forces were mounting their seaborne invasion.

The first step was to take control of a two-storey yellow-brick gatehouse that German soldiers were using as a barracks. At 1 a.m., a small band of men crept into the gatehouse to discover there weren’t any enemy soldiers left inside to take by surprise. They examined the dishevelled state of the bunk beds—enough to hold 100 men—and suspected that when the Allied bombs began to fall, the Germans had fled. But where?

The men split up. A few were stationed inside, some hunkered down in the ditch, and others, including Ross, took up positions around the gatehouse. Suddenly, gunfire sprayed the outside road, and a large shell crashed into the lower part of the building. A couple of dazed paratroopers stumbled out, unhurt. The answer was now clear: the Germans had retreated to a concrete trench fortified by machine-gun bays and a 75-mm anti-tank gun. “We only had pistols, rifles and a two-inch mortar,” says Ross. They were outgunned and outnumbered.

“Where are the rest of your men?”

For the next nine hours, the Germans fired with impunity at the Canadians. Ross and two others crawled into a ditch beside the road and tried to take the enemy down. Peppered by gravel as bullets narrowly missed his head, and up to his waist in stinging nettle, he aimed his submachine gun at the flashes coming from the enemy trench. “We kept firing,” he says, “but it was too dark to know if any of the rounds we squeezed off hit anyone.”

Not so for the enemy’s big weapon, which landed a direct hit on a second-floor window of the gatehouse, killing six men, none of whom had reached their 25th birthday. Ross didn’t have a view of the carnage, but he heard the shell rip through the wall and the sound of brick and plaster hitting the ground. He returned fire until the sun came up and a paratrooper snuck closer to destroy the Germans’ 75-mm gun with four mortar bombs.

At 10 a.m., the shooting stopped and Ross counted 42 enemy soldiers marching down the road to surrender their weapons in front of the gatehouse. As one of C Company’s signal operators, Ross radioed headquarters. “This is Charlie C,” he said and gave the code word, “blood,” which meant “success”—they were in control of Varaville.

“Where are the rest of your men?” a shocked enemy sergeant asked Ross in English. He’d been ordered to surrender because they were up against an unbeatable force of battle-hardened Canadians. “You’re looking at them,” Ross answered, pointing to the small band of paratroopers who gave the Allied Forces one of their first victories.

After the war ended, John Ross returned to civilian life. He continued to skydive, with his last drop at age 80.

Check out 20 powerful Remembrance Day quotes to share on November 11.

The Code Breaker

By Carmine Starnino

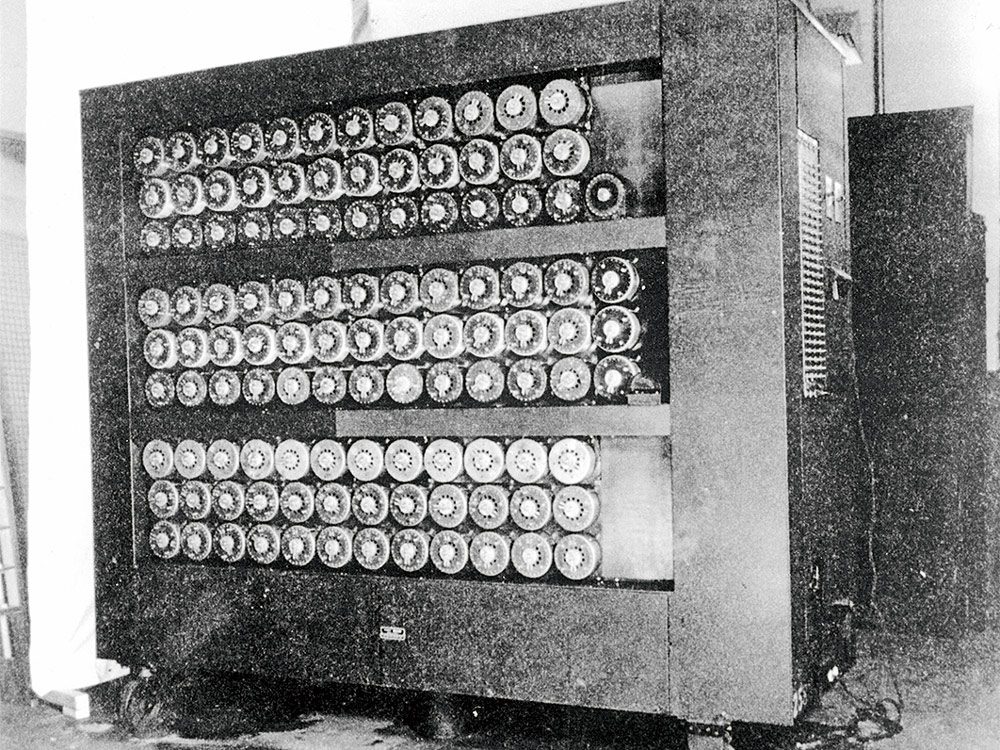

It was June 6, 1944, and for Madge Janes, the war was noise. At midnight, in a northwest London building surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, the 21-year-old entered the bay—an auditorium-size room filled with the burning smell of hot machines—and steeled herself for the clanking din of her comrade-in-arms: a two-metre-high, two-metre-wide steel behemoth called a bombe.

Janes knew the moment of the big invasion had arrived. The third officer handed her a menu, and she studied the sheet, covered with complex flow charts of numbers and letters. She stepped briskly to the rear of the machine, whose exposed back, with its mass of plaited red wires, resembled a telephone switchboard. Janes plugged the wires into sockets in the order specified by the menu. She returned to the front, where she faced rows of coloured drums, each with the letters of the alphabet engraved around its circumference. She set the drums and watched them whir.

Janes removed her navy-blue wool uniform jacket and hooked it neatly on the back of the chair. She sat. She waited. The drums were now a rackety blur. Her job was to stay sharp, to ensure the one-ton device suffered no interruption as it unriddled the correct setting needed to read the day’s intercepted German radio traffic. The bombe was dogged: cranking through the millions of combinations the Nazis might have used to cipher their messages, it nixed the improbable options, selected the promising ones. Seventy-five machines rolled 12,600 hours a week, staffed by over 400 operators. They never stopped. It was brute-force decryption. Code breaking on an industrial scale. Janes just wished she had earplugs.

“You’re killing boys overseas if you don’t get those settings.”

Eight months earlier, after signing up with the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens) in Portsmouth, England, Janes and her sister Gene were rousted from sleep in the early hours and thrust into a paddy wagon with six other scared young women. They were driven to a building in Eastcote, where they were trained on the hellish intricacies of the fickle contraption. How, if the steel-wire brushes on a rotor came undone, it would short-circuit; how you’d rush to reposition the wires with tweezers to reset the drums for another run. The women learned other things: how the noise would rise from your feet and thrum in your head; how, after an eight-hour shift, you’d stagger to bed, stupefied with fatigue. It wasn’t long before the first Wrens had a nervous breakdown, collapsing in their quarters in tears.

The pinch-faced third officer patrolled the rows. “Hurry up,” she shouted at a girl struggling with her machine. “You’re killing boys overseas if you don’t get those settings!” All day, Janes fought off visions of Allied men trapped in sinking vessels, with desperately needed supplies plunging to the ocean floor.

“We got it! We got it!”

Janes lit a cigarette, exhaled and watched the spinning drums. She had little contact with the rest of the navy and, except for rare trips to the pub, was sealed off from the town. Not even her family or her Canadian fiancé, Spitfire pilot John Trull, knew what she did. Officially? She was a “writer”—a secretary. Some Wrens felt their family’s disappointment that they weren’t playing a bigger role in the war. Janes mulled what life would’ve been like if she and her sister had joined the nurses, as they had planned. She would be tending to the wounded men she was, in secret, trying to protect. Many Wrens had boyfriends and husbands in combat. Janes’s brother was in the navy. She felt, with every message she helped decipher, she was saving his life.

The tickety-tock stopped: a setting was found. There were cheers (“We got it! We got it!”), as everyone knew some threat on this important night—a bombing raid, a torpedo—had likely been thwarted. Janes jotted down the numbers and ran the slip over to the checking machine. After it was tested, a dispatcher relayed the information by secure telephone to Bletchley Park, where mathematicians would use it to unscramble their store of German transmissions. Janes then walked back to her desk, where she was handed a new menu, and began again.

Madge (Janes) Trull eventually moved to Mississauga, Ontario. Her husband, John Trull, passed away in 1999.

Read on to find out how Cree code talkers from Alberta helped win World War II.

The Soldier

By Malcolm Johnston

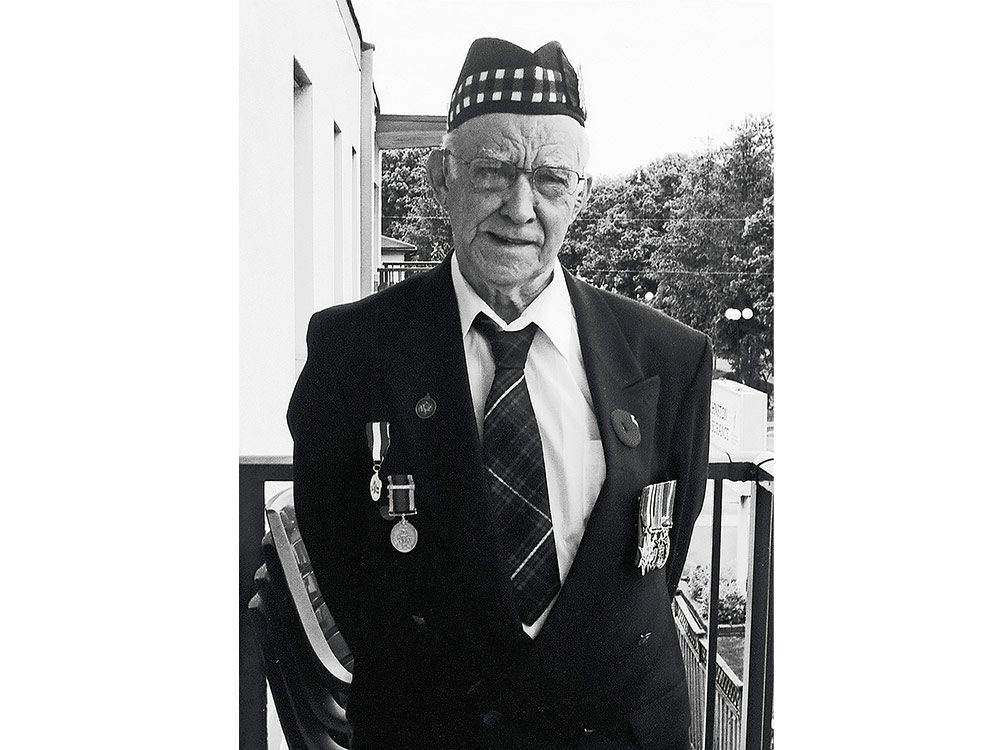

They called them “potato mashers” for their long handles and cylindrical metal tops. Orval Gibbons traced the German grenade against the sky as it sailed over the dike near Hoofdplaat, Holland. It landed in the grass five metres away, midpoint between him and his friend, a French-Canadian private named Nelson Thibeault.

In one fluid movement, Gibbons barrel-rolled over a log and covered his head as the grenade detonated, sending debris and metal fragments zinging overhead. The 21-year-old stood, staying low so as not to give snipers an easy target. He conducted a quick inventory: limbs intact, no blood, no pain. He was okay.

A sergeant in the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, a regiment in the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, Gibbons had already faced death weeks earlier on June 6, 1944. He was among the first to rush out of the Landing Craft Assaults that carried soldiers directly onto Juno Beach. From his seat, Gibbons could see explosions ahead, as land mines obliterated the lead ships. When his ramp flipped down, the sight was devastating. Bodies in crumpled positions lay everywhere.

“I belted him in the kisser, then gave him his gun, but I made sure it didn’t have any bullets.”

Atop the dunes, Germans lay in wait, armed with sniper rifles and anti-tank guns. As Gibbons stepped onto wet sand, bullets zipping past, a mine exploded to his right, lodging shrapnel deep in his shoulder. Fortunately, adrenalin numbed him to the pain. Fighting their way over the dunes—dodging sniper fire and heavy artillery—Gibbons and the Glens advanced on the French towns. By midnight, they had seized Basly, six kilometres inland. Gibbons’s swollen shoulder began to throb. Medical staff shipped him back to England for three weeks of care before returning him to the action shortly after July 7. By then, the Glens had captured Caen—a key road junction—reaching the town’s centre on July 9.

After rejoining his regiment, Gibbons learned threats didn’t always come from the enemy. One night, a soldier from the 17th platoon was on a rampage: he had discovered Thibeault was seeing his girlfriend back home and wanted the French-Canadian dead. Gibbons snatched the soldier’s gun and told him to retrieve it once he’d sobered up. When he returned in the morning, no less belligerent, Gibbons responded in kind. “I belted him in the kisser, then gave him his gun, but I made sure it didn’t have any bullets.” The incident brought Gibbons and Thibeault closer. They spent hours reminiscing about home, girls and sports.

By the fall, the Glens had orders to secure the Scheldt Estuary, an entry point for Allied supplies. On the day the potato masher came arcing over the dike, Germans had dug trenches and mounted a fierce resistance.

“Your husband saved my life.”

His ears still ringing from the grenade blast, Gibbons signalled to a private to strafe the German line. As he did, Gibbons and his company poured over the dike. Minutes later, they achieved their objective: capturing a dozen German soldiers. But Gibbons realized he’d lost track of Thibeault. He backtracked along his route and found his friend lying at the scene of the explosion. His inner thigh bore a gaping hole. Thibeault writhed on the ground, gritting his teeth. He was bleeding out; there wasn’t much time.

Gibbons pulled up Thibeault’s pant leg and applied a tourniquet to the wound. He hoisted his friend onto his back and carried him several hundred metres to the medical tent. As staff tended to the injury, Gibbons wished him well, then hurried back to the front lines. The two men never saw each other again during the war. Thibeault was relieved of duty because of the severity of his injury.

When the Germans surrendered on May 7, 1945, the Glens had pushed all the way into Germany’s Hochwald Forest. Gibbons was honourably discharged with the rank of lance corporal.

Today, Gibbons lives in Orillia, Ontario, with Audrey, his wife of more than 50 years. In the early 1990s, Gibbons and Audrey tracked down Thibeault, who was living north of Sudbury. When Thibeault opened his front door, he told Audrey, “Your husband saved my life.” Audrey was astonished. Gibbons had never mentioned the ordeal. In fact, in the years after the war, he discarded his uniform, service records and most of his medals. “Medals are crap,” says Gibbons. “I always cared more about what my buddies thought of me.”

Next, check out 30 powerful Remembrance Day stories from Canadian veterans.