In the ’90s, I was living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, making a shabby living writing magazine articles, when a peculiar assignment came my way. The Dalai Lama had received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. My Tibetan friend Paljor Thondup, who had heard that he was planning a tour of the United States, invited him to visit our town. The Dalai Lama accepted.

At the time, he wasn’t the international celebrity he is today. He travelled with only a half-dozen monks, most of whom spoke no English. Nor did he have any money.

As the date of the visit approached, Thondup hatched a plan. He called the only person he knew in government, a young man named James Rutherford, who ran the governor’s art gallery. Rutherford had a rare genius for organization. He and a contingent of volunteers undertook to arrange the Dalai Lama’s visit.

They borrowed a stretch limo from a wealthy art dealer and had Rutherford’s brother Rusty drive it. Thondup persuaded the proprietors of Rancho Encantado, a luxury resort outside Santa Fe, to provide free food and lodging. They asked me to act as the Dalai Lama’s press secretary.

The Dalai Lama arrived on April 1, 1991. I was by his side every day from 6 a.m. until late in the evening. Travelling with him was an adventure. He was cheerful and full of enthusiasm-asking questions, joking about his bad English. He would stop and talk to anyone, no matter how many people were trying to rush him to his next appointment. When he spoke to you, it was as if he shut out the rest of the world to focus his entire sympathy, attention, care and interest on you.

He rose every morning at 3:30 a.m. and meditated for several hours. In Santa Fe he had to attend dinners most evenings until late. As a result, every day after lunch, we took him back to Rancho Encantado for a nap.

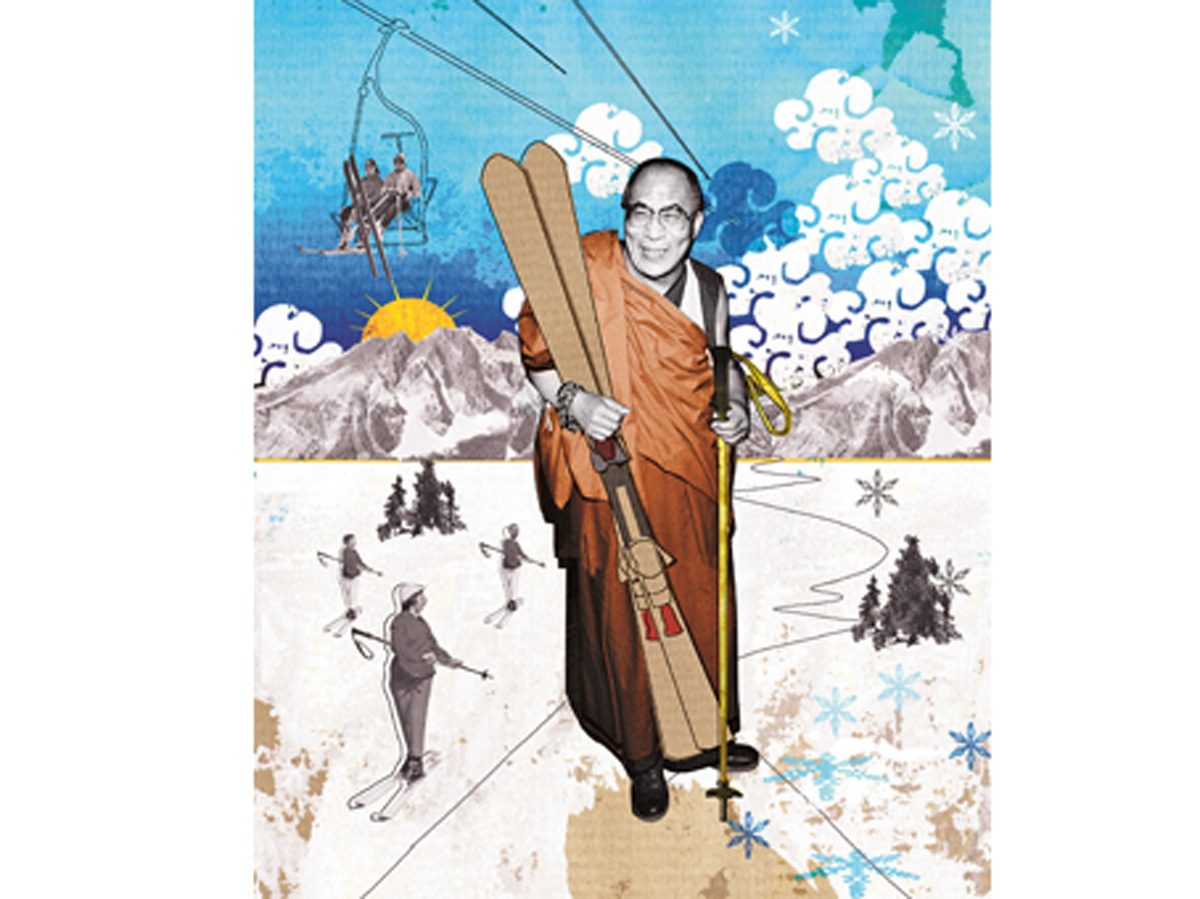

On the penultimate day of his visit, the Dalai Lama met with senators from New Mexico and the state’s governor. During the luncheon, someone mentioned that Santa Fe had a ski area. The Dalai Lama seized on this news and began asking questions about skiing-if it was difficult, who did it, how fast they went, how they kept from falling down.

After the event, the press corps dispersed. Nothing usually happened when the Dalai Lama and his monks retired for their afternoon nap. But this time something did. Halfway to the hotel, the Dalai Lama’s limo pulled to the side of the road. A moment later Rusty got out and came over to us. He leaned in the car window.

“The Dalai Lama says he wants to go into the mountains to see skiing. What should I do?”

“If the Dalai Lama wants to go to the ski basin,” Rutherford said, “we go to the ski basin.”

The limo made a U-turn, and we all headed toward the mountains. Forty minutes later we found ourselves at the ski basin. The mountain was still open. We pulled up below the main lodge. The monks clambered out of the limo.

Rutherford disappeared and returned five minutes later with Benny Abruzzo, whose family owned the ski area. Abruzzo was astonished to find the Dalai Lama and his monks milling about in the snow, dressed only in their robes. They looked around with keen interest at the activity, the humming lifts, the skiers coming and going, and the slopes rising into blue sky.

“Can we go up mountain?” the Dalai Lama asked Rutherford.

Rutherford turned to Abruzzo. “Well, can he do it?”

“I suppose so. Just him, or-?” Abruzzo nodded at the other monks.

“Everyone,” Rutherford said.

Abruzzo spoke to the operator of the quad chair. Then he opened the ropes. A hundred skiers waiting in line stared in disbelief as the four monks, in a tight group, gripping each other’s arms and taking tiny steps, came forward. Underneath their maroon-and-saffron robes, the Dalai Lama and his monks all wore the same footwear: oxford wingtip shoes. Wingtips are terrible in the snow.

The operator stopped the machine, one row of chairs at a time, to allow everyone to sit in groups of four. I ended up sitting next to the Dalai Lama, with Thondup to my left.

The Dalai Lama turned to me. “When I come to your town,” he said, “I see big mountains all around. Beautiful mountains. And so all week I want to go to mountains.” The Dalai Lama had a vigorous way of speaking, in which he emphasized certain words. “And I hear much about this sport, skiing. I never see skiing before.”

“You’ll see skiing right below us as we ride up,” I said.

“Good! Good!”

We started up the mountain. The chairlift was old, and there were no safety bars, but this didn’t seem to bother the Dalai Lama, who spoke animatedly about everything he saw on the slopes. As he pointed and leaned forward into space, Thondup begged His Holiness to please sit back, hold the seat and not lean out so much.

“How fast they go!” the Dalai Lama said. “Look at little boy!”

We were looking down on the bunny slope, and the skiers weren’t moving fast at all. Just then, an expert skier entered from a higher slope, whipping along. The Dalai Lama saw him and said, “Look-too fast! He going to hit post!” He cupped his hands, shouting down to the oblivious skier, “Look out for post!” He waved frantically. “Look out for post!”

The skier, who had no idea that the 14th incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion was crying out to save his life, made a crisp little check as he approached the pylon, altering his line of descent, and continued expertly down the hill.

With an expostulation of wonder, the Dalai Lama sat back and clasped his hands together. “You see? Ah! Ah! This skiing is wonderful sport!”

We approached the top of the mountain. The monks and the Dalai Lama managed to get off the chairlift and make their way across the mushy snow in a group, shuffling cautiously.

“Look at view!” the Dalai Lama cried, heading toward the back boundary fence of the ski area, behind the lift, where the mountains dropped off. He stared southward. The Santa Fe ski basin, situated on the southernmost peak in the Sangre de Cristo mountain range, is one of the highest ski areas in North America. The snow and fir trees and blue ridges fell away to a vast vermilion desert 1,500 metres below, which stretched to a distant horizon.

As we stood, the Dalai Lama lapsed into silence, and then, in a voice tinged with sadness, he said, “This look like Tibet.”

Then the Dalai Lama pointed to the opposite side of the area, which commanded a view of 3,700-metre peaks. “Come, another view over here!” And they set off, in a compact group, moving swiftly across the snow.

“Wait!” someone shouted. “Don’t walk in front of the lift!”

It was too late. I could see the operator, caught off guard, scrambling to stop the lift, but he didn’t get to the button in time. Just then four teenage girls came off the quad chair and were skiing down the ramp straight at the group. A chorus of shrieks went up, and they plowed into the Dalai Lama and his monks, knocking them down like red-and-yellow bowling pins. Girls and monks all collapsed into a tangle of arms, legs, skis, poles and wingtip shoes.

We rushed over, terrified that the Dalai Lama was injured. He was sprawled on the snow, his face distorted, his mouth open, producing an alarming sound. Was his back broken? Should we try to move him? And then we realized that he was not injured after all, but was helpless with laughter.

“At ski area, you keep eye open always!” he said.

We untangled the monks and the girls and steered the Dalai Lama away from the ramp, to gaze safely over the snowy mountains of New Mexico.

He turned to me. “You know, in Tibet we have big mountains.” He paused. “I think, if Tibet be free, we have good skiing!”

We rode the lift down and headed to the lodge for cookies and hot chocolate. As we finished, a young waitress with tangled, blond hair and a beaded headband began clearing our table. She stopped to listen to the conversation and finally sat down, abandoning her work. After a while, when there was a pause, she spoke to the Dalai Lama.

“Can I, um, ask a question?”

“Please.”

She spoke with complete seriousness. “What is the meaning of life?”

In my entire week with the Dalai Lama, every conceivable subject had been broached-except this one. People had been afraid to ask the

really big question. There was a brief, stunned silence at the table.

The Dalai Lama answered immediately. “The meaning of life is happiness.” He raised his finger, leaning forward, focusing on her as if she were the only person in the world. “Hard question is not, What is meaning of life? That is easy question to answer! No, hard question is, What make happiness? Money? Big house? Accomplishment? Friends? Or-” he paused. “Compassion and good heart? This is question all human beings must try to answer: What make true happiness?” He gave this last question a peculiar emphasis and then fell silent, gazing at her with a smile.

“Thank you,” she said. “Thank you.” She got up, finished stacking the dirty dishes and cups, and took them away.

Slate Magazine (February 26, 2014) Copyright © 2014 By The Slate Group, slate.com