How DNA Testing is Solving Cold Cases—and Reuniting Families

These DNA reunion stories show how genetic testing can be a powerful tool in solving missing person cases—decades after the trail went cold.

In 2018, Jeff Highsmith of Texas started a Facebook page on behalf of his family. The page had one objective: to find Melissa Suzanne Highsmith, Jeff’s sister. At just 21 months, she had been abducted from Fort Worth by her babysitter 51 years earlier and the family was desperate for answers.

In addition to the Facebook page, they made flyers with baby Melissa’s face and age-progression photos that indicated what she might look like now, in her 50s. Remarkably, they were convinced she was still alive all these years later, and determined to be reunited with her.

They knew that more tools were now available to help locate missing persons—such as genealogy kits with DNA tests. And so, the family bought kits from 23andMe, and then uploaded the results to a public database called GEDmatch.

It seemed like a shot in the dark, but it worked. In November 2022, the Highsmith family found Melissa through a key DNA match: Melissa’s daughter. By pulling the threads of DNA matches, triangulating connections on a much bigger family tree, they zeroed in on the baby snatched so long ago. The family reunion was a joyful one. Melissa described being found as “the most wonderful feeling in the world.”

The story of Melissa Highsmith and her family got global news coverage. But it’s only one of many DNA reunion stories. In Toronto, siblings separately adopted from Romania when they were babies were reunited in their 50s when both took a DNA test to learn more about their biological health; turns out they had spent much of their lives within a 30-minute drive of each other. And two sisters—one in the United Kingdom, the other in the Netherlands—met for the first time in 75 years after learning that they share a Canadian father.

There are countless cases. In Spain, a DNA database has been set up to identify the “stolen babies” of the Franco dictatorship. Black Americans are using DNA tests to learn about family lineages disrupted by slavery. And stories about recent tragedies—including the devastating February earthquake in Syria and Turkey—have included details about how DNA was being used to reunite children with their parents.

Much of the news coverage of DNA technology advances has focused on capturing a killer or identifying a long-dead victim. But there’s another, equally compelling possibility: solving cold cases involving a living victim or missing person. In other words, someone out in the world, location and identity unknown, who can be made aware of who they really are only through DNA.

Law enforcement agencies have stepped up efforts to utilize it, and private businesses have also hopped on board, creating databases and putting the tools for DNA collection into the hands of consumers. Crucially, there’s also been a rise in citizen sleuths and investigative genetic genealogists, perhaps bolstered by our insatiable love for true crime, who are helping to bring ordinary families together again.

Advances in DNA Analysis

According to Michael Marciano, director of research for the Forensic and National Security Sciences Institute (FNSSI) at Syracuse University’s College of Arts and Sciences, there have been major advances over recent decades in how forensic DNA analysis is done. One has to do with sensitivity—meaning, our ability to detect lower amounts of DNA than ever before. That means researchers can now identify the DNA that’s deposited from someone touching an object or a person.

It also means that mixed DNA samples (samples that include more than one person’s DNA) can be disentangled. “For example, a perpetrator enters a bank, picks up the pen where you fill out your deposit slips, writes a note and gives it to the teller,” says Marciano. “We know the perpetrator picked up the pen, but how many other people did? Their DNA might be on it too.” Now, it’s much easier to isolate the perpetrator’s genetic material.

The second major development has to do with how results are analyzed. Software and computing power have improved sufficiently that we can create better models and more accurate statistics that help analysts interpret the samples they’ve collected.

But still, to get a match, researchers must be able to link a sample to a DNA profile. “Forensics is about comparisons,” says Marciano. “If I have a fingerprint or DNA profile but nothing to compare it to, I can’t determine whose it is.”

This is where databases of DNA profiles come in. Sometimes, those profiles are derived from court-mandated samples or samples collected from crime scenes or missing persons cases. Dean Hildebrand runs a forensics lab at British Columbia Institute of Technology, and for decades he has done work for the province’s coroner service, running DNA samples that primarily come from missing persons or their families. Some are from remains found at scenes. Other times, he runs samples from the belongings of a missing person—a blanket the person couldn’t sleep without, or a pair of broken glasses left behind.

“We have an avalanche of those samples coming through all the time,” says Hildebrand. Many are attached to long-cold cases. More than a decade ago, Hildebrand helped develop a missing persons database so law enforcement officials can log unidentified remains and the samples from missing persons.

The Genealogy Boom

But lately, DNA searching has had little to do with foul play. Companies such as Ancestry.com, 23andMe, FamilyTreeDNA and MyHeritage have sold consumers on the idea of uncovering their heritage and making connections. It’s DNA analysis as a party game for the whole family.

And it’s very popular. By the start of 2019, according to MIT Technology Review, more than 26 million people had sent their DNA to one of four commercial ancestry and health databases.

These products and their analysis are the result of technological advancement; 20 years ago, it wouldn’t have been possible for you and your family to spit in tubes, put them in the mail, then receive a report on your lineage. But they also reflect a growing social phenomenon: a fascination with drawing connections and insights into the self through the use of genetic material.

“When you have a lot of good quality DNA, you can capture a lot of information about an individual,” says Nicole Novroski, assistant professor in the department of anthropology at the University of Toronto. She says that the databases of private ancestry or genealogy kit companies really grew, and then came the option to put your DNA sample on public databases allowing people to make additional connections.

GEDmatch is one such public database. It allows users to compare samples across a broader spectrum than a single site, looking for matches with overlapping genetic material. The bigger the overlap, the more likely the match is a close relative such as a parent, child, grandparent or first cousin.

“Sometimes, it’s a dead end,” says Novroski. “But the more people in the database, the more potential there is to make a connection, even if it’s a far-out one. Then it’s the genealogists’ and the investigators’ job to kind of rebuild all that missing information for these big family trees or kinship determinations.”

Novroski says that the work of armchair detectives, uploading samples and combing through DNA matches, can yield a mixed bag of implications. “It’s doing a lot of good by solving cold cases,” she says. “But some people don’t like the information they find, especially when there’s been infidelity and things of that nature that were previously not known or discussed.”

The number of public and private databases for genetic identification is growing. In China, authorities keep a database that includes the DNA of parents of missing children, and of any children found by police. The system was thrust into the spotlight in 2021 when a family was reunited with their kidnapped son after 24 years—a case that also drew attention to the devastation of living with the uncertainty of a loved one’s disappearance.

Before the family was reunited, the son’s father, Guo Gangtang, spent years criss-crossing the massive country in his determination to find his son, Guo Xinzhen, often sleeping outdoors and travelling by motorbike with flyers and a flag displaying his son’s image. Without the help of DNA, he likely would never have found his son. According to Chinese media, thousands of missing children have been found thanks to the database.

Investigative Genetic Genealogy

The desire to connect with family members, missing or not yet discovered, has given rise to another phenomenon: Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG). IGG takes all the newly public DNA information being uploaded to genealogy websites and combines it with other sources of public and private data—such as Facebook profiles, marriage records and even worn paper copies of family trees—to infer relationships and build out networks of people.

It’s as much a social phenomenon as a technological one, and a wave of IGG investigators are now working in tandem with families and law enforcement to find missing persons and solve longstanding mysteries. One famous recent example is when an IGG investigator, a retired attorney with a PhD in biology named Barbara Rae-Venter, helped police track down California’s “Golden State Killer,” who had eluded authorities for decades, by combing through DNA of the killer’s distant relatives.

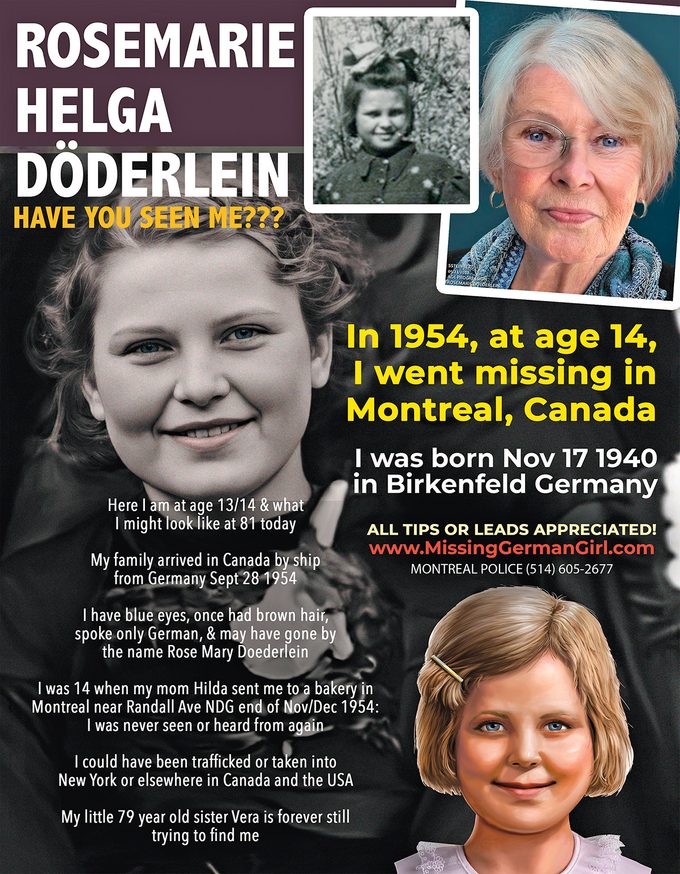

But IGGs are also being consulted to help families find long-lost relatives. In March 2022, California-based Christa Hastie decided to help her mother, Vera, 80, solve a family mystery: What had happened to Vera’s sister, Rosemarie, when she vanished from the streets of Montreal one winter day in 1954 at the age of 14? Over six months, Vera and Christa dedicated themselves to searching for any and all information related to Rosemarie’s disappearance.

Christa already had a DNA profile on Ancestry, and now she added profiles to other major sites. She also got an investigative genealogist to help her zero in on the maternal matches. They found a DNA match close enough to be Rosemarie’s grandchild, but when Christa reached out to the person, they claimed not to know Rosemarie.

Since Vera had been born in Germany, she and Christa enlisted the help of a genealogist with experience in DNA testing in that country. Carolin Becker put Vera’s grandmother’s surname into a database she had constructed, and her software found nine generations of ancestors. “A whopping 34 pages of tiny text,” says Christa.

Becker cross-referenced the data with matches from DNA sites, ruling out anyone who wasn’t both a maternal and paternal match to Vera. And she helped Christa and Vera reach out to long-lost relatives, adding their DNA to the family tree and bolstering the search.

Ultimately, more than 900 people fleshed out that family tree, dating to the 17th century. Using DNA Painter, a website with geneology research tools, Christa was able to re-confirm the specific match: Rosemarie’s granddaughter, who had been identified before.

Christa reached out again, this time with proof, and Christa and Vera connected with Rosemarie’s whole family. The truth was astonishing: Rosemarie had died years earlier, but her life hadn’t ended when she disappeared all those decades ago; she went on to have children and grandchildren. So while there would be no reunion, no explanation for Rosemarie’s disappearance, knowing she had not been murdered was a huge comfort to Vera.

There was another upside to their search: Because the IGG helped them map out a comprehensive family tree, they were united with or introduced to relatives they now keep in touch with. Christa and Vera emerged from this exercise with an expanded sense of family.

That’s exactly the promise of commercial DNA sites. And it’s easy to imagine any number of positive outcomes. We now have the capability to reunite lost family members separated by war or other circumstances. We can pinpoint the ancestral homes of adoptees or others whose biological connections have been severed.

But now imagine a less rosy scenario: A family tries DNA kits as a fun activity, swabbing the inside of their cheeks while standing around the dinner table, and then eagerly awaits the results—only to have those kits show, unexpectedly, that one of the kids is not a biological match. “The more information we’re collecting from our DNA, the more we open this Pandora’s box of ethical considerations,” says Hildebrand. “Because there can be big surprises awaiting—some of them really great, and some shocking.”

The privacy implications can also be astounding. At least one consumer site (GEDmatch) now has an opt-in clause allowing what you upload to be searched by law enforcement and the public. Since DNA is shared between biological family members, if a relative uploads theirs to one of these sites, they are potentially implicating you, because their DNA is linked to yours. So anyone who wants to, say, anonymously donate sperm or give up a baby for adoption could one day be identified—even if they never provide their own DNA sample.

“I think it’s a very powerful thing,” says Hildebrand, adding that if only around 10 percent of people add their DNA samples into one of these public or private databases, we would be able to identify every human on earth.

And that comes with benefits and drawbacks. “As people get more into this, we’ll be closer to the point where you pretty much can’t hide,” he says. “It’ll be possible to link every family in the world.”

For the Highsmith family, who were happily reunited in Texas after decades apart, DNA was the link. “Our finding Melissa was purely because of DNA, not because of any police/FBI involvement, podcast involvement, or even our family’s own private investigations or speculations,” notes one Facebook update. “DNA WINS THIS SEARCH!”

Next, check out Canada’s most notorious cold cases.