A Canadian Minister Needed a Stem Cell Donor. This Young German Man Stepped In

Dominic Leblanc won seven elections. But he was unlikely to win against non-Hodgkin's lymphoma—until a young overseas donor came to his rescue.

The young man being greeted by a staffer from the Office of the Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs, Infrastructure and Communities is neither a politician nor a foreign delegate. Jonathan Kehl, 23, is a student from Bad Hersfeld, a town in Germany. Travelling with his friend Dennis Bolender, he’d never set foot in Canada before he deplaned in Ottawa on September 25, 2022. He was whisked to a hotel where Minister Dominic Leblanc was waiting. Emotions were high as the two men hugged.

Though they’d never met in person, they felt close: Jonathan Kehl’s blood had been coursing through Dominic Leblanc’s veins for three years.

In 2000, Dominic Leblanc, the son of former Governor General Roméo Leblanc, graduated from law school and began what would be a long political career when he was elected the Liberal MP in the New Brunswick riding of Beauséjour. He has since been re-elected seven times, led various government departments and served as the president of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada.

Brimming with energy, he’d never shied away from a heavy workload. But on Saturday, April 20, 2019, Leblanc, 55, felt so under the weather—exhausted and feverish—that he consulted a physician at Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre in Moncton.

He was convinced he’d caught a flu bug, but a biopsy of the lymph nodes in his armpit said otherwise: He had a rare and very aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. And it had started to attack his liver. In a Hail Mary attempt to control its progress, he underwent strong chemotherapy.

“We weren’t sure he’d make it,” says his hematologist-oncologist, Dr. Nicholas Finn. Adds Leblanc: “I found out later that if the treatment hadn’t worked, I would have lived only a few more weeks.”

Dominic Leblanc’s wife (Jolène Richard, former chief judge of the Provincial Court of New Brunswick), and his stepson Shelby remained by his side throughout the ordeal. Fortunately, the three-week cocktail of drugs put the cancer into remission. Leblanc returned home for a short time, but the battle was far from won. Still, he was convinced he’d be cured. After all, he’d already survived chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2018.

The search for a donor

The medical team knew that the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma would return if Leblanc didn’t have a stem-cell transplant. It was his only chance of survival. The procedure is relatively simple in theory: kill all the tumour cells in the bloodstream and then introduce stem cells from a healthy donor’s bone marrow to regenerate the immune system.

“We had to work fast, while he was still healthy,” says Finn. Stem-cell transplants aren’t done at the Moncton hospital, so in June 2019, Leblanc was sent to Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont in Montreal for tests. “He was as yellow as a lemon because of the liver failure and had lost a lot of weight,” remembers Dr. Sylvie Lachance, who oversaw his care. Still, doctors believed he was strong enough for the transplant.

One of Leblanc’s younger sisters volunteered to donate her stem cells, but she wasn’t a match. And so began the search for a donor in Héma-Québec’s stem-cell bank, which has more than 55,000 registered donors, and in the international bank, which lists 40 million donors in 55 countries.

“For a transplant to work, you need an HLA match,” explains Susie Joron, manager of donor-search strategies and stem-cell distribution at Héma-Québec. Human leukocyte antigens are genetic markers that are essential to a healthy immune system. In August 2019, the perfect match popped up on a screen at Héma-Québec.

Twenty-year-old Jonathan Kehl lived with his parents and two sisters in Bad Hersfeld, a small town in the German state of Hesse. He’d registered as a stem-cell donor two years earlier, in 2018, when the German National Bone Marrow Donor Registry brought its awareness campaign to his high school. “Back then, I didn’t even know it was an option,” he admits. A year and a half later, he was a university student doing his teacher training when he got a surprise call from the German stem-cell bank. His cells were fully compatible with those of a potential recipient.

“I could have said no, but I agreed,” says Kehl. “I wanted to save a life! It was a really emotional moment for me, and for my family, who encouraged me to donate.” The donation was anonymous; all he knew was that his stem cells would go to a Canadian man.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Leblanc was elated when Lachance told him the good news—especially because the chance of finding a perfect match is only one in 20,000. On August 31, 2019, he was admitted to the hospital for 10 days of intensive chemotherapy that wiped out his immune system and blood cells.

Meanwhile in Germany, Kehl made the 150-kilometre journey to the Frankfurt Red Cross to receive injections meant to stimulate his stem-cell production prior to donation. On September 16, 2019, it was time to harvest the cells. “I felt weak,” he says, “but they told me it was normal because of the cell stimulation.”

Sitting in an armchair, he watched as blood was drawn from his arm and sent to a centrifuge to separate the stem cells (a half-litre in total was collected). The rest of the blood’s components were put back into Kehl’s body. As soon as the procedure was over, the life-saving stem cells were put in a cooler and jetted to Canada. The transplant was scheduled for 48 hours later.

At around 2 p.m. on September 18, 2019, a nurse clad in head-to-toe protective gear walked into Dominic Leblanc’s Montreal hospital room and carefully connected the small tube containing the stem cells to a catheter in an artery just above his heart. It was a moment of profound solemnity. Leblanc’s wife, both anxious and happy, was by his side as events unfolded.

The beige substance was administered intravenously for two hours. Though the infusion went smoothly, it was followed by a period of uncertainty. It takes 14 to 21 days for the new blood cells to regenerate, and another week for any to appear.

“I was afraid it hadn’t worked until Dr. Lachance came into my room with a smile and told me the neutrophils—the white blood cells—had materialized. That was proof that the transplant was a success!” says Leblanc.

He remained in isolation and was administered daily infusions of blood, platelets, antibiotics to fight infection, magnesium and potassium. “The chemotherapy was so powerful that I had ulcers in my mouth and was fed intravenously for five weeks.”

To pass the time, he read a lot and followed his team’s campaign to get him re-elected. On the eve of the French-language TV debate on September 30, 2019, his old friend Justin Trudeau paid him a surprise visit. Says Leblanc, “I was really touched to see him. He sat there with me for two hours, gloved and masked, discussing politics and laughing despite the serious circumstances.”

Three weeks later, glued to the tiny TV screen in his hospital room, Leblanc whooped with joy when voters in his New Brunswick riding of Beauséjour re-elected him for a seventh term. Still, his biggest win came on November 5, 2019: Every single cell in his bloodstream was from his donor. He could finally leave the hospital, more than two months after he’d been admitted.

But he wasn’t out of the woods yet. He would have to remain in Montreal for another month to undergo tests three times a week at Hôpital Maisonneuve- Rosemont. “The day I received my transplant, the doctors told me it was like being reborn,” Leblanc says.

High on his renewed lease on life, he wanted to thank his donor personally. And so he filled out a document that would be given to Kehl—but only when two years had passed since the transplant. “That’s an international rule that exists to make sure the transplant really worked,” explains Joron.

In January 2020, Dominic Leblanc returned to Ottawa to the applause of the members of the House of Commons. Only his lack of hair, which had fallen out due to the chemotherapy, hinted that he’d been ill. He was starting to feel healthy again, but “I have the immune system of a four-month-old,” he jokes. “It’s coming back slowly, and I have to be careful. It’s getting better and better.”

But he often thought of the man who saved his life. In 2021, two years after the transplant, Dominic Leblanc was on his way to the Ottawa International Airport when he got an email from Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont: They had his donor’s information. Leblanc was dumbfounded. He had the donor’s name, Jonathan Kehl, and some information about him.

“I was struck by his age—he was born in 1999,” says Leblanc. He excitedly asked an aide to look up his benefactor on Facebook. He was adamant about getting in touch with him.

Dominic Leblanc meets his donor

Stéphane Dion, then Canada’s ambassador to Germany in Berlin, suggested Leblanc write his donor a message in English and have it translated into German. “You saved my life, and I am extremely grateful for your generosity,” Leblanc wrote.

When Kehl received the note, he was stunned. He and his mother searched the internet for Leblanc’s name, and all signs pointed to him being a Member of Parliament. “It was unbelievable!” exclaims Kehl.

Four days later, Leblanc’s heart pounded as he read the reply. “After all this time, I am very happy to know you are well,” Kehl wrote in English, which he’d been learning since he was nine. They set up a virtual meeting two weeks before Christmas.

“I was so touched when he said he felt responsible for my health,” says Leblanc. The men spent time talking about what they’d been through, and Leblanc invited Kehl to visit him in Canada when the pandemic subsided.

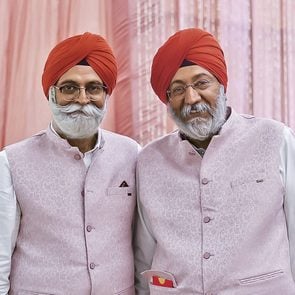

“This young man saved my life,” said Dominic Leblanc as he proudly introduced Kehl to the correspondents and photographers on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on September 28, 2022. Kehl was overwhelmed by the welcome, which was usually reserved for foreign dignitaries. Prime Minister Trudeau extended his heartfelt congratulations for the young man’s generosity.

Kehl’s whirlwind trip included a quick stop in Montreal and then a few days of salmon fishing on New Brunswick’s Miramichi River, where he revelled in the majestic landscapes (despite not catch- ing anything). “Everything was beautiful,” says the young man.

Though he was happy that his host promised to visit him in Germany, Kehl felt heavy-hearted as the parliamentarian drove him to the airport to catch his flight back home. He had the strange impression that he was leaving part of himself behind.

“Jonathan’s extraordinary gesture gave me a second life,” says an emotional Leblanc. The chances of his cancer returning get lower and lower with time, but if he ever needs another stem-cell donation, Kehl has promised to come to the rescue of the man he now feels forever connected to.

“I consider Mr. Leblanc to be my genetic twin,” he says.

Next, check out this deep-dive into how DNA testing is helping reunite families.