What I Want the Medical Students Who Studied My Parents’ Donated Bodies to Know

After long lives and hard battles with illness, my parents lie beside each other in a medical lab. If the students look closely, maybe they will see evidence of the love that bound them together.

Written on the body

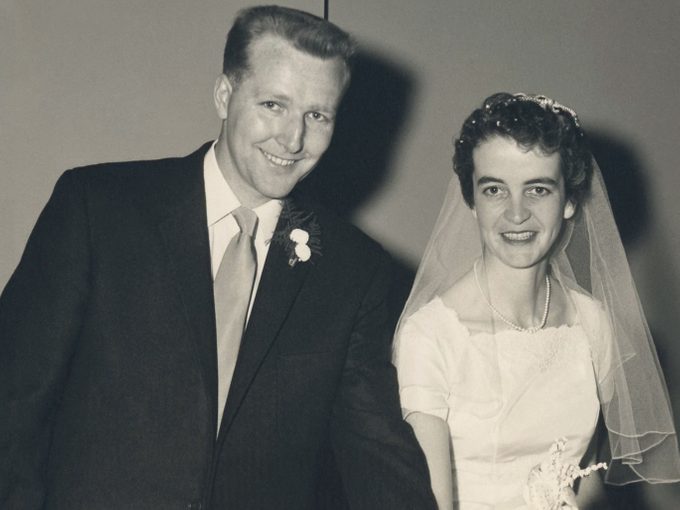

My parents died within weeks of each other. Mom left in November 2017 and Dad followed her in January. They were both 85 years old, their birthdays having been just a day apart. They had been together since they were 17, meeting on a summer evening at the Wagon Wheel Dance Hall in the small community of Pointe-du-Chêne, N.B. Growing old, they both remembered details from that long-ago Saturday night, when Mom wore a soft yellow sweater set and a pair of pedal pushers, and Dad, nervous, made his way across the floor to ask her for a dance.

As they were aging, they never discussed or specified their care needs or wishes; Mom was especially reticent to talk about it. But they knew that after dying, they wanted to have their bodies donated to a medical school. That was a long-standing and clearly stated desire, and my brother and sister and I were proud of them for making that decision. After they passed away, their bodies were taken to a medical school laboratory where they stayed for close to a year and a half, teaching a new generation of health care professionals.

I filled out a form that invited us to tell the students what we thought was important for them to know about Mom and Dad. Another form asked for medical information. I wrote a couple of paragraphs about both of them and listed their many medical conditions. The woman who coordinated the donation program assured me that Mom and Dad would lie side by side in the lab, and that the students who worked with them would know they’d been married. Some years prior, I had the opportunity to spend time in the anatomy lab of the medical school where I was working, and I would have loved to know more about the people whose bodies I was looking at.

I wanted the students to pay attention to my father’s hands. They would see that his left hand was rough, the fingers calloused and bent from decades of creation in his workshop. There might even be speckles of paint on the palm or the finger on which he rested his paintbrush.

Dad had a massive stroke when he was only 58 and, as a result, he lost the use of his right hand; perhaps a student would notice that it was the softer hand. For years after that stroke, he tried, unsuccessfully, to bring life back to that paralyzed hand, massaging and exercising it. Luckily, his dominant hand was the left one—thank fate for such a mercy.

I hoped his fingernails were trimmed. As he aged, he became more and more sensitive and it was increasingly difficult to cut his nails. And maybe he was less trusting of his grown children to do the job the way he wanted it done.

Over the decades that followed his stroke, Dad became an artist, making thousands of dollhouses, birdhouses and pieces of furniture, giving them to family and friends. Then, when age sanded his words away, he sat and painted. Hundreds of paintings. His art gave him a voice when his speech had been twisted. His workshop and, in time, his bedroom, gave him a place to craft beauty in wood and paint and whimsy—the joy of creating.

When those students would look at my mother’s back, I wished a volume of things. I hoped for them to notice the pathway of pain that was my mom’s crooked spine. That pain aged with her and, in time, put her in a wheelchair, bending her neck low. And when they would examine her heart, I wished for them to know that it had been troubled yet tough. Perhaps a student cardiologist would note the wonky valve that caused her so much fear throughout her life and, just maybe, that student would also be touched by the fact she had loved so fiercely with that heart. She did not love perfectly, but she did so mightily, and worked every day of her life to love better.

And when Mom’s brain would be studied, I wished that the future neurologist would see the worn passages of anxiety and the dark pools of depression, and be impressed by the way she navigated life with that brain. I wanted them to know that she was funny and smart, and, once in a while, very brave.

I wished that the students learning to read the human body would see Dad’s lion heart. I imagined it large, bruised, scarred but strong. He fell in love that summer night so many years ago—surely that was marked on his heart, which would also have been cracked over and over as both he and Mom battled their ways through deep illness. That demon stroke must have burned into his heart, too, but he lived on after it, defying the wicked clot that tried to take him away.

I wished for the students to see Dad’s throat, where there must have been a battalion of words, trapped. He fought to find them and to speak, right up until the day he was put to bed and demanded I take his glasses off. He died three days later.

The students would perhaps notice the crooked bones of his hips, and I hoped they would realize the pain he was in when he sat with Mom, and she with him, at the end of their long lives together. Finally, I wished for them to look at Dad’s brain, with its increasing damage. I wished to say to them: Imagine the strength it took to stay through all of that, and to do it because of love and duty and that long-ago dance.

For those with eyes to see, Mom and Dad’s bodies were tapestries.

Next, read about one man’s connection to a fallen First World War soldier.

© 2019, Linda E. Clarke. From ’My parents died months apart, but lay together in a lab for students’’, The Globe and Mail (June 19, 2019), theglobeandmail.com