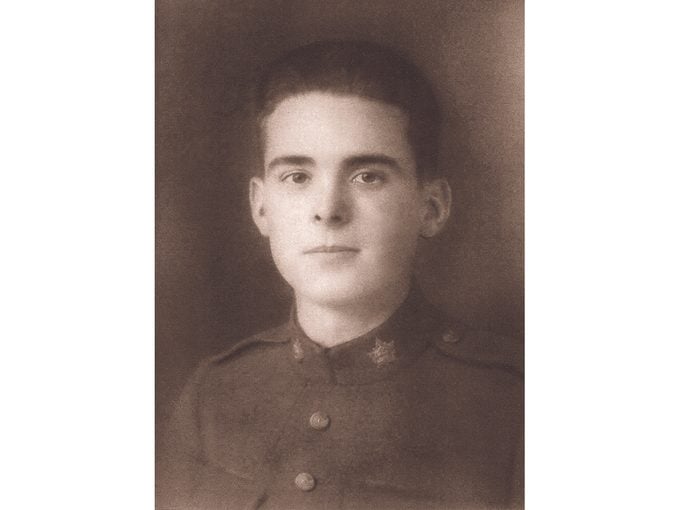

War Forced My Father Into Manhood at an Early Age

Not having a birth certificate at the time of enlistment, he was unaware that he had joined up as a 15-year old.

During the early 1940s, four veterans of the First World War lived within a two block radius of our home, in Stratford, Ontario. One had served with General Edmund Allenby in the Middle East campaigns. Another, a shell-shock victim, would stand in his mother’s yard, stiff as a ramrod, for hours on end, occasionally throwing his arms around but never saying a word. Our father’s best friend lived down the street from us, and was still alive after surviving a gas attack and the horror of being buried alive. Then there was our dad, George William Trowsdale, who carried shrapnel in his right leg to the grave.

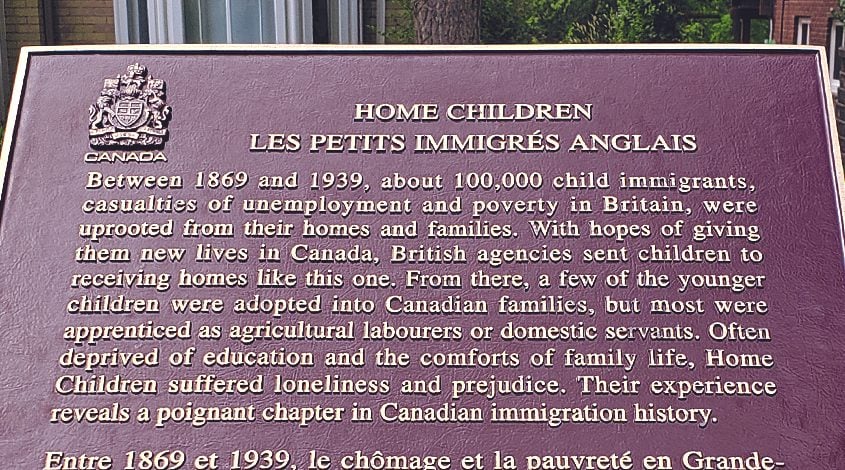

Dad and his younger sister were born in an English workhouse. Decades later, she told my sister Brenda and me how they had searched railway tracks, looking for partially burned cinders for their winter heat. When their father died and their mother disappeared, they ended up in two separate Catholic orphanages. The one my father attended was called The Children’s Homes of the Sheffield Union. In 1913, he sailed for Canada as a “home child” immigrant, and worked as a farm labourer near Tillsonburg, Ontario. Enlisting in the Canadian army on March 9, 1916, he didn’t find out his true date of birth—August 20, 1900—until sending in an application for his birth certificate in 1927. At the time of enlistment, he was unaware that he had joined up as a 15-year old.

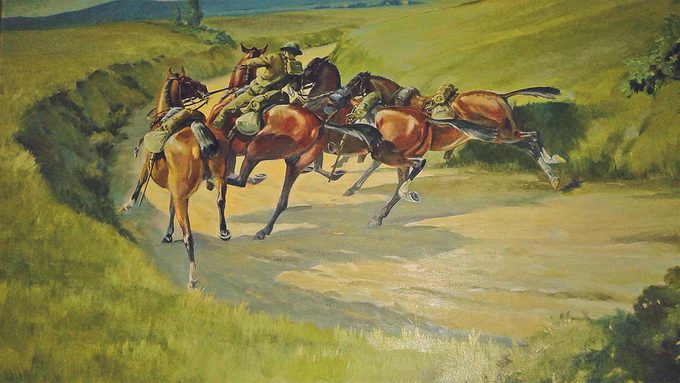

He served initially in the 168th Battalion, and then transferred to the Machine Gun Squadron of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade on March 7, 1917. I first heard about his transfer during a conversation he had while purchasing a painting of a First World War cavalry machine gun squadron, in Vancouver. Wounded in Trouville, France, in 1918, he was discharged from an Australian field hospital several months later in Rouen, France, and left without his collection of war souvenirs. The only specific item I remember he brought back was a German Uhlan cavalry helmet.

He decided to move back to England in 1919, but when he found out that his aunt, whom he had sent his pay for safekeeping, had disappeared, he returned to Ontario and settled in Stratford after a brief stay in Detroit.

He only ever told us three war stories. The first was about his decision to give up his sergeant’s stripes because of what he had to enforce. The second was about his punishment in the “glass house,” a military prison for soldiers who have broken certain rules. The only thing I recall him saying about that was, “once was enough.” The last story he ever told us was about his decision not to join three friends who had been members of the North-West Mounted Police (later the RCMP) before enlistment and wanted him to join them after demobilization. Brenda and I always found it amusing when he struggled to admit that our mother, who had grown up on a farm and could do almost anything associated with horses, was actually just as good, if not better, at handling them than he was.

Upon his return from the war, he began correspondence courses for a high school certification and also worked as a machinist’s helper for the Canadian National Railway. His first major purchase as soon as he saved up enough money was a piano, which still remains in our family home in Stratford. He began taking piano and voice lessons, decided to enter a singing class in Ontario’s first competitive music festival in 1927 and ended up winning the first-place prize. I can still remember being played to sleep at night with one of my favourite 1920s songs, “Doll Face.”

After completing the courses necessary for promotion to full machinist, he went on to survive the Depression. Rather than taking out a mortgage on a house that was built in 1858, he decided to rebuild it himself.

With a major interest in Freemasonry, he achieved his ambition of getting accepted into the Shrine, but passed away just before his oft-stated goal of living to three score and ten. An important part of his life from the early ’30s until his death in 1969 was the Masonic Lodge in Stratford.

It’s estimated that there are now over three million descendants of the more than 80,000 British home children who came to Canada between 1875 and 1933. Not only was this our personal legacy, it was the legacy of many other Canadians as well.

Check out more Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.