How I Tried to Be a Good Neighbour During COVID-19

When my city shut down during the pandemic, I started putting friendly signs in my window to check in on neighbours I had never met.

My kitchen window is above my sink. The washer of dishes and rinser of celery and lettuce can look out and imagine doing other, better things. Our window looks into the kitchen window of our neighbour’s house, so close to ours. Our houses are old soldiers in a row, shoulder to shoulder on a worn out street in downtown Ottawa.

The view into our kitchen is often lit up, like a blaring, glaring movie set. But our neighbours, two young men who I only know in passing, never seem to turn on their kitchen light. Sometimes, as I do my dishes or rinse our apples, my eyes adjust. Shadow gives way to shape and bent head and striped sweater emerge. Then I see them, standing at the sink, leaning in and down, washing a dish or a tomato or dumping the pickle juice from the empty jar. I am startled every time.

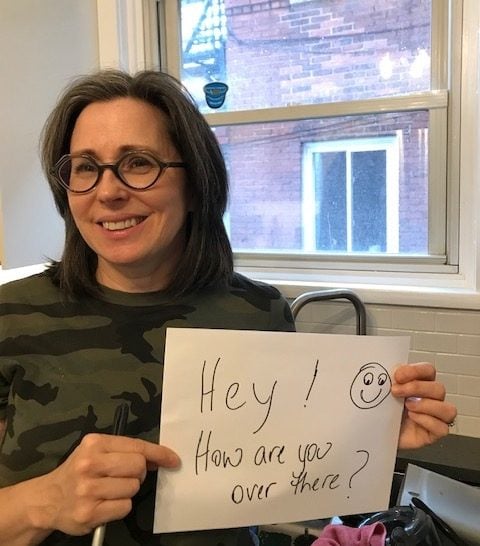

Though I don’t know these men, on the first Saturday of the first weekend of the COVID-19 lockdown I still wanted to be a good neighbor. I made a sign that said, “Have a nice day,” and stuck it on my kitchen window, with a smiley face. A while later that day, they taped up a sign on their window with a message for us.

“Thank you. You too!”

We went on like this for a few days, back and forth, like an echo, and I thought of how this would be a nice story for us all: how we communicated by signs throughout the whole pandemic—every single day!—and moved from strangers at the beginning, to such good friends by the end.

“Mom, you’re so cool,” my 21-year old daughter said.

Somewhere around Day 5, I positioned Beaker the Muppet in the window, and they met him with a cute stuffed dog. Then, I raised the bar much too high with a fragment of a Mary Oliver poem about spring, and that was the end of that. Maybe I was showing off.

By this time, I was also running into the guys in the driveway sometimes as we walked our dogs, so the notes had already started to feel a little silly. What if my notes were chore to them, and not charm? What if I was less like a mother, and more like an annoying weirdo?

So, I stopped. About a week later, my dog was yelling at their dog in our backyards. I saw one of the guys when I went out to shush him.

“Sorry, we didn’t find a poem,” he said.

“We meant to,” he added, “And then we never did.”

“That’s okay,” I replied. “DEWEY. SHUT UP!” And we both went back inside.

It is so hard to know what it means to be a good neighbour in these days. None of the old tricks work. We can’t show up and knock on a door, or even lend things. I’ve thought about baking cookies and dropping them off, but that feels illegal.

Going for walks make me sad, or mad. I like what walks do for my health, but not what they do to my heart. I hate veering away from people, like we are all infected. It’s depressing, and we avoid my favourite blocks of Bank Street, Ottawa’s long stretch of a street that reaches from near the bottom of Parliament Hill, cuts through my Centretown neighbourhood, and continues much further than I could ever walk even in normal times. It’s just too crowded with other veering, lurching people.

How do I love thee neighbour, like I’m supposed to? Love should pull in, not push out. Love takes risks, not the side road to avoid a crowd. Love drops off casseroles and attends funerals, always. Love is best and easiest in person, up close and brightly lit, not hidden in the shadows. And sick people are for visiting, not avoiding.

I can’t love like I’ve been taught. We are all just stumbling along.

So, like everyone I guess, I have been turning in, instead, and caring for my family with roast chicken and pineapple crumble and quite a few frittatas, as it has turned out.

Being only and always with my family means that kind of love is also stretched and challenged. There is no question that our neighbours on the other side, with whom we share the thin walls of our semi-detached 120-year-old house—a house that has stood and not fallen through two world wars, a depression and the Spanish Flu—have now heard me yell. That’s okay. Love is loud.

After this is all over, I have decided I will finally have our neighbours from both sides, the left and the right, over for dinner. I will pack our house with neighbours. We will sit on the couch together. I can’t be a neighbour now, as I’d like to, but I can be a neighbour then. We will all have lived through this together. The pandemic might have knitted us together like an old worn sock, even after it’s over—because it is finally over.

I will write this invitation on a piece of paper, and stick it on my kitchen window for them to read, for old, bad time’s sake. Maybe we can have a little laugh together, about how we tried to be kind, even during a time when we didn’t really know how.

Karen Stiller‘s new book The Minister’s Wife: a Memoir of Faith, Doubt, Friendship, Loneliness, Forgiveness and More releases in May 2020, and is available to pre-order now.