How I Said Goodbye to My Beloved Horse

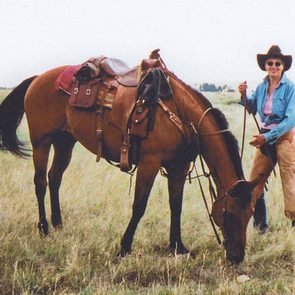

During my horse Roany’s final days, our extraordinary bond only grew stronger.

Horse of a Different Colour

Last summer, I put my old horse in the ground. But there’s way more to the story than that. Roany spent 39 years on the planet, and 25 of those were with me.

The first thing I noticed about him were his kind eyes; the second was his size—just under 17 hands (1.72 metres) at the shoulder. The Santa Fe cowboy who sold him didn’t tell me much, but within days I came to understand Roany’s intensely good nature. Each morning when I went out to feed him, he greeted me with a just-happy-to-be-here chortle.

He was as solid a trail horse as I’ve ever ridden, never flinching in big wind or while crossing water, or even when two mule deer, hidden by some willows, leaped in front of him. He was so bombproof that the county search-and-rescue team enlisted his help a few times a year to find and deliver a wayward hiker.

I bought Roany the same year I moved to a ranch in Creede, Colo., because Deseo, my alarmist Paso Fino horse, decided it was the scariest place he’d ever been. I counted on Roany to keep the whole barnyard calm, not just Deseo and the miniature donkeys but also the ewes and lambs, the recalcitrant rams, the aging chickens and me.

Like all roan horses, Roany’s coat marked the changing of the seasons. In the dead of winter, he was burgundy with tiny white flecks. In March, he would shed to a dappled grey with rust highlights. By midsummer he was red again, but not as rich. And when his heavy coat grew back in October, he was solid grey for most of a month.

I stopped riding Roany when he turned 33 because I thought my old friend deserved a lengthy retirement, though he stayed strong until a few months before his death.

His decline started with a bout of lameness in April and a longer one in May. By late June, he was limping more often than not. When Doc Howard came for a ranch call, he said, “There’s a number associated with this lameness, Pam, and it’s 39.”

I did the things there are to do: supplements, an ice boot, various anti-inflammatories and painkillers. We’d had very little snow and no spring rain, and for the first time in my tenure the pasture stayed dormant all summer, the ground extra hard on sore hooves.

Roany loved nothing more than the return of the spring grass, and it seemed radically unfair that in what was looking to be his last year, there wouldn’t be any. I watered, daily, a thin strip of ground between the corral and the chicken coop and called it Roany’s golf course.

He had some good days there, but mostly he hung around the corral. That summer, between my fiancé, Mike, my ranch helpers, Kyle and Emma, and me, Roany hardly had a moment’s peace. We iced his legs and groomed him twice daily, mixed canola oil into his grain to help keep weight on him, and hugged him constantly.

He seemed bemused by all the attention. Every time we set the water in front of him, he took a giant drink, and I suspect it was more for our sake than his. One day, Kyle, not knowing I was out there, set a bucket down next to Roany not three minutes after he had drunk three-fourths of a fresh bucket for me. Roany looked at Kyle for a minute, glanced over at me, then lowered his head to drink again.

Roany was stoicism defined. As his condition worsened, he learned to pivot on his good front leg—and he would, for an apple or a carrot or to sneak into the barn to get at the winter’s stash of alfalfa. He blew bubbles in his water bucket because it made me laugh, and he would sometimes even give himself a bird bath by splashing his still-mighty head.

I also knew that just because he could handle the discomfort it didn’t mean he should. He had been so strong so recently, a force of nature thundering back and forth across the pasture. There was no chance I was going to ask him to make another winter, but as long as he was hobbling to his golf course and chortling to me each morning, it seemed too early to end his life.

A sweet goodbye

Among Mike’s many gifts is a deep intuition about the suffering of people and animals, so I paid attention when he said, on a Monday night in mid-August, “This is entirely your decision, but if you want to put Roany down this week, I could take Wednesday afternoon off.”

The next day I saw a slight downturn in Roany’s condition. He ate his food, drank his water, and stood for his treatments, but there was something a little lost in his kind eyes. I called Doc and made the appointment for Wednesday afternoon, with the caveat that I could cancel if Roany’s condition improved or I lost my nerve.

By Tuesday night, Roany was swaying, just slightly. He ate, but with a little less enthusiasm than usual. I went out to check on him at 8 p.m. and then at 10. The moon was bright and the coyotes were singing. Even by this light I could see that Roany was holding his body like he didn’t feel right inside of it.

I woke at 4:30 with the kind of start that always means something has happened. I grabbed a flashlight and rushed to the corral, but Roany wasn’t there, nor on his golf course, nor in the yard.

I called his name and heard hoofbeats coming hard across the pasture. I indulged the fantasy that after weeks of suffering he was miraculously cured. Then I heard Deseo: my hot-blooded alarmist, my early-warning system, my tsunami siren. He skidded to a stop and butted his head against my chest, seeming to say: About time you got here.

I started out with Deseo beside me, heading for one of Roany’s favourite spots at the back of the property. When I turned at the quarter pole, Deseo whinnied again: Not that way, human. By this time, Mike was crossing the pasture to meet me. Deseo whinnied again, and we followed him to another favourite spot—a shady stand of blue spruce at the base of a hill. It was the first time since last summer that Roany had been out that far.

He was still standing when I got there. But the minute he saw me, he went to the ground. He curled up like a fawn, and I could hear that his breathing wasn’t right. Mike and I sat beside him and petted his handsome neck.

Above us, stragglers from the Perseid meteor shower, which had peaked over the weekend, streaked the blackness. Pegasus, the biggest horse of all, galloped across the sky. We listened to Roany’s breathing and the coming of dawn. Deseo stood nearby, head lowered.

Roany stretched out his long legs and put his head in my lap. I thanked him for taking good care of the ranch animals, including the humans, including me. I told him I’d be okay, that we’d all be okay, and he could go whenever he needed to, but he went on taking one slow breath after another.

Kindness of others

On one of Roany’s first bad days, a compassionate horsewoman named Debbie innocently asked me how I was. My answer was no doubt more than she’d bargained for, but on that day she became my adviser in horse eldercare and pain relief.

I told her my fears: I had made difficult decisions with beloved dogs, but the length of a horse’s life and the sheer size of its body makes everything trickier. Debbie promised that, when the time came, she would send her husband out on his track hoe to dig the hole, never mind that they lived off-grid more than 30 kilometres away.

Now, I called Debbie to say I thought we were close. Then, I called Doc to say I thought we might not need him. It was finally daylight, but the sun hadn’t risen. Mike and I were shivering, so he slid into my place to hold Roany’s head and I ran to get sleeping bags. When I got back across the pasture, Roany’s head was still in Mike’s lap, but now he was struggling for breath.

“Touch him,” Mike said. I knelt and put my hand on his big red neck. Roany took one breath and then another and then the last breath he would take forever. “I think he was waiting until you got back.”

A moment later, the first rays of sun came over the hill, turning the sky electric. I crossed the pasture one more time to get Roany’s brushes to groom him for burial. Debbie’s husband, Billy Joe, had a dozen things to do that morning, but he arrived at the ranch not long after I called.

I don’t know Debbie very well, and Billy Joe hardly at all, but as much as anything else this is a story about the way people in my town care for one another. When I tried to pay Billy Joe for his time, or even for gas, he shook his head and said, “An old cowboy doesn’t take money to bury an old horse.”

If there is such a thing as a good death, Roany had one. It was almost as if he had heard Mike’s offer and said, All right then, Wednesday, and how about in that stand of spruce on the other side of the hill? I’ve always said Roany was a horse who never wanted to cause anybody trouble. He remained that horse till the last second of his life and beyond.

Late that night, I watched the Perseids burn past my window and imagined my old Roany up there, muscles restored to their prime, and his shining burgundy coat alongside the white of Pegasus, both of them with their heads held high, and galloping.

Outside (May 2019), Copyright 2019 by Pam Housons, Outsideonline.com.

Next, find out what it’s like photographing Alberta’s wild horses.