With Some Help From My Favourite Dishes, I Finally Found Joy in Cooking

In learning to be comfortable with what I don’t know, I’m realizing that the things that make me feel as though I can’t cook don’t have to be true forever.

For a man raised in a patriarchal culture, my father loved to cook for his family. We lived in Uganda and, later, in Kenya for about two years as refugees. Since we didn’t have an indoor kitchen, he would light a fire outside of our home. He’d cook sukuma wiki, a dish of collard greens, onions and tomatoes, and serve it with ugali, a porridge made of cornmeal and water. We ate this in the refugee camp, and it remains one of my favourite meals.

My mother left our family when I was five—war has the power to come between a mother and her children. I never met my father’s mother, or jaaja in the Luganda language. But if my dad’s cooking took after that of my jaaja, she was phenomenal.

My father didn’t cook often—we ate once a day and other family or community members would feed us. But when he did, it was worth the wait. If he started making dinner at 4 p.m., you wouldn’t expect to eat until at least 10 p.m. He liked to take his time, cutting ingredients into pieces so tiny that the onion was practically puréed. He also loved his pili pili peppers: tiny red and green chilies he would munch on at every meal. The smell of his cooking would overpower our home, including the one in London, Ont., where we moved to in the mid-1980s, when I was 10 years old.

With his friends, my father was the life of the party—he would host get-togethers that would go into the early hours of the morning. I washed dishes, enthralled with the loudness of the adults and how happy they all seemed. Looking back, that joy was what freedom felt like. Their dancing revealed a vulnerability that wasn’t afforded to them during the war. When my father was cooking, he was happy. But if he wasn’t, he could be unpredictable. I often felt like he resented my presence.

I left home when I was 16, and from then on, I lived on my own in London before moving to Toronto. I really only knew how to make pancakes and scrambled eggs because in our family, I was responsible for making breakfast on weekends. My father would say that his mom taught him how to cook because she didn’t want him to rely on anyone to take care of him. But he never passed on the same knowledge to me.

The woman who sponsored us to come to Canada, whom I’ve since called granny, turned the kitchen into a place of love. When we left refugee housing, she moved us next door to her house, and we lived there for about three years. On Sundays, she would make potato stew, cheesecake and lemon meringue pie. We would listen to Louis Armstrong and watch movies in her basement. She knew me better than I knew myself.

From my mid-teens to early 20s, I lived on a steady diet of ramen noodles and pasta with canned sauces. Cooking at that time in my life was perfunctory; cleaning the toilet brought me more joy. Being in the kitchen made me miss my granny and reminded me of the loss of my mother, who is still alive.

Unlike many things in my life, not knowing how to cook wasn’t something I could gloss over or joke away. So I avoided thinking about it. It was only when I had kids in my 30s that I realized I had to learn.

I’d listen to a friend tell me in detail how she made puréed baby food from scratch, while I fed the jarred stuff to my toddler. I watched in awe as another friend baked cookies for parent-teacher nights. I’m a resourceful person, but not knowing how to cook for my kids made me feel stuck and guilty.

The time I spent in the kitchen only clarified what I lacked. Should the pot be hot when I add the onions? Should the butter be room temperature? Should I use baking powder or baking soda? The absence of family recipes, secrets passed down the line, was a reminder that elders are missing from my life.

When my son was around two, I realized I had to feed him solids. I took to Google in search of “easy” recipes and also sought out inspiration on Instagram. I looked for reassurance that with time and patience, I could do it. There have been failures—I once baked chocolate chip cookies so hard they chipped my daughter’s tooth—but I keep trying. And in learning to be comfortable with what I don’t know, I’m realizing that the things that make me feel as though I can’t cook don’t have to be true forever.

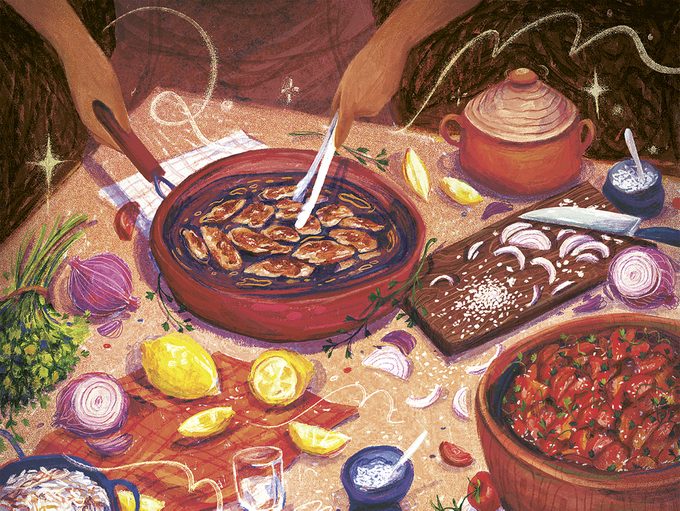

Once my kids were ready for full meals, I tried to recreate my father’s stewed chicken, one of his favourites. The dish includes minced onions, tomatoes, salt and curry served with white rice and a salad of tomatoes, onions, lemon juice and cilantro. I would fry the chicken separately first and then add the rest of it into one pot with water. That handful of ingredients connects me to a simpler story of family, one that I imagine was the same for my father when his mother, my jaaja, was still alive.

And then last year, the pandemic lockdown pushed me into the kitchen not just out of necessity but also curiosity. What began as an activity to pass time with my kids, like trying out different recipes and making vanilla cupcakes, has become a slow peeling away of the conviction that I can’t learn to cook.

One afternoon, I surprised myself when I made a loaf of bread. Yes, I used the wrong type of yeast and the dough rose to an incredible height, but it baked into a crispy exterior with an inside as soft as any bread I’d bought from a bakery. And then I finally made a batch of cookies that didn’t hurt my daughter’s teeth.

Standing in my kitchen can be daunting, but I remind myself that those feelings are just a beginning, a place to create cooking traditions of my own that I can pass on to my children. As I stand at the stove, I know the story doesn’t end with me.

Next, learn about the Toronto charity that feeds thousands with surplus restaurant food.

© 2020, Namugenyi Kiwanuka. From “Finding Joy in the Discomfort of Cooking,” Chatelaine (September 14, 2020), chatelaine.com