The Cottage Chair That Helped One Man Learn How to Sit Still

Woodie Stevens has been spending summers at his Canadian cottage since he was a kid. From finding the love of his life to appreciating the joys of quiet contemplation, his family's homemade chair has seen him through it all.

From the time he was four years old, Woodie Stevens has spent every summer of his life at his family cottage in the Thousand Islands, a 10-minute boat ride from Gananoque, Ont. But it wasn’t until his 20th summer at the cottage, when he thought he had that part of the province all figured out, that the islands and the river reached out and spoke to him—and changed the course of his life.

Woodie, born Ford Woods Stevens, is now 79 years old. He’s a career dentist in the Philadelphia area, a gentle soul who can spin a good yarn. His cottage, which has been in the family for more than a century, sits atop the highest point on Wyoming Island, some 18 metres above the St. Lawrence River. It features an impressively level stone patio just outside the door, a perfect plateau of Canadian Shield granite, courtesy of Mother Nature. The patio faces downriver to the east but also offers a clear view south toward Grindstone Island, just across the invisible line in the water that marks the Canada-U.S. border.

The Thousand Islands were Woodie’s summer playground as a kid, the place where he learned how to swim and paddle and fish, and how to get into and out of trouble. At age 15, he and his pal Gordie once found a giant anchor stone at the bottom of the river and decided to haul it out of the water and up to the patio. It took them five days.

By the time he’d reached his 20s, Woodie was living a carefree and careless life. “I was full of beans as a young man,” he says. “Always running around, always talking.”

Then, one beautiful morning in the mid-’60s, he woke up early and saw his father, Ford Stevens Sr., out on the patio.

His dad (also a dentist, and one of the founders of the Academy of General Dentistry) was sitting in one of the family’s homemade chairs, which they call “island rock chairs.” They look like a pre-historic prototype of a Muskoka chair, the kind of thing an archaeologist might unearth. They have the same sloped seat, wide armrests and tall backrest. But they are less rounded than Muskoka chairs, more angular and boxlike. The backrest is made of only two wide slats of wood. The armrests are untapered. The chair’s rudimentary appearance is key to its charm.

“He was having a coffee and watching the sunrise, so I got up, got some coffee and went out. Of course, I was full of bubbles and that stuff, and he just went, ‘Shh,’” Woodie recalls. “He said, ‘Quiet. Sit down. Sit down and listen.’”

Woodie sat in the island rock chair his dad had made for him when he was just a kid. Woodie obviously wasn’t inclined toward quiet serenity at this point in his life, but the chairs, with their reclined seats and backrests, have a way of encouraging people to settle. He gently lowered himself into the seat and the chair took hold of him, and he tried listening for a change.

The problem was that Woodie truly had no idea what he was supposed to listen for. Voices? Motorboats? A malfunctioning septic system? “I said, ‘Listen to what?’ And Dad said, ‘Sit and listen.’ I thought I was in trouble again so I kept quiet.” Moments passed. Then his dad said, “Listen to the river. ”

Woodie listened. He was sitting on an island with the mighty St. Lawrence rushing past him on all sides, but to him the river had become inaudible. It took him a while to locate the sound of its churn beneath the loon calls. You have to listen past the wind to hear the water. Finally, he heard it and isolated the sound in his mind. Then he looked at the river anew. “My dad said, ‘This river has passed by this island for millions of years at six miles an hour. You’ve got to design your life like that.’”

It was an epiphany to him: those words, spoken in this place at that moment, suddenly gave him a new perspective on his life, his family, adulthood, the world. The lesson he took from the moment wasn’t that he needed to slow down to six miles an hour, and it wasn’t just that he needed to find a more sustainable pace for his life. He also understood that he needed to learn to halt life’s perpetual rush, fast or slow, and be still—and that his grandfather, as it happened, had designed the perfect chair for this very purpose. Even when you’ve got an island cottage like Woodie’s—as literal a metaphor as you’ll ever find for stepping outside the fray—it’s not an easy thing to do.

The Stevens clan has, through generations, been characterized by its combination of hospitality and contemplation, which helps explain how the family ended up with this cottage in the first place. Wyoming Island got its name from its initial purchasers, two Methodist ministers from Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley. They quickly decided the island was big enough for four families and, recognizing they had a rare opportunity to choose their neighbours, in 1910 invited two of their friends, young family men both, to come visit, and to buy in.

One of those friends was Woodie’s grandfather, Junius Stevens. He purchased the island’s southeast corner, which happened to be its least accessible area from the water, yet its most majestic once scaled (funny how those things go together, adversity always leading to reward). Junius then contracted a Grindstone Island farmer, Hiram Russell, to build a one-room camp and to complete it in time for the following summer.

Back then, it was arguably easier for Hiram Russell to build that camp than it was for Junius Stevens to go and enjoy it. The Stevens family’s voyage to their summer retreat was an annual crucible, and it is a testament to their destination’s beauty that they endured it. At 420-odd kilometres, the trip from Kingston, Penn., to Gananoque, Ont., which is roughly the same distance as Ottawa to Toronto or Edmonton to Banff, lasted three whole days. Junius owned a motor car and drove it—with his wife, Fannie, and their two children—on unpaved and badly potholed roads, stopping repeatedly to fix flat tires and to push through muddy ruts.

There were no hotels or motels along the way; just roadside tent camping and campfire cooking. The trip was capped by a ferry ride from Clayton, N.Y., to Gananoque, and then 90 minutes of toil in a rowboat to Wyoming Island.

Nor was life any easier once they arrived. There were regular rowboat outings to Grindstone for milk and other necessities, and all the cooking took place outside on that stone patio. All this in order to spend the summer in a one-room cabin with an outhouse.

Junius designed and built his original island rock chairs out in the open here, as well. The original chairs he built for himself and Fannie are still there on Wyoming Island, beneath their favourite pine tree.

Skip forward a century or so, and that one-room camp is now a three-bedroom cottage with a full kitchen, plus a second building that features its own miniature suite and, around back, a giant workshop with every tool you could possibly need. The second suite is for Woodie’s brother, Jim, and his wife, Darlene; as the family has grown, so has the

family compound. As their kids have become adults, they all

share in the cottage’s operating expenses, with everyone paying annual dues for taxes, repairs and maintenance. It’s an unsentimental way to organize the business end of the family cottage, but it works. Once everyone pays up, they are free to indulge in relaxation and nostalgia.

These days, Junius’s 72-hour excursion has become, for Woodie, a six- hour drive from Philadelphia to the Gananoque marina and a 10-minute ride in Chips, the family’s vintage mahogany motorboat.

“If you think you really like a girl,” Ford Stevens Sr. told his restless son back in the ’60s, “bring her here.” This was the sagest piece of advice Woodie’s dad gave his sons about choosing a partner. Island cottaging isn’t for everyone: even when you’re not alone you remain symbolically surrounded by a void, outside life’s currents, cut off from the rest of the world. Some people—the Stevenses, for example—find that liberating. Others find it suffocating. If your steady likes it here, explained Ford, the relationship has potential. If not, it’s doomed.

This is precisely what Woodie did when he met young Lini Westland on a nearby Howe Island dock in 1971. Woodie, 29 at the time, was out on the water with two friends, zipping around in one of his buddies’ motorboats, when they spotted three girls sunbathing at Bishops Point one summer afternoon. Lini, then 21, was sharing a cottage rental with two friends. The boys offered them a boat ride, and Lini’s friends said yes. Lini thought the whole thing was sketchy, but she wasn’t about to leave her friends or be left alone on Bishops Point.

Woodie and Lini hit it off immediately. Woodie told her he was planning to go back to school and become a dentist. “When he told me that, I realized he had a dream and some ambition,” she says.

Woodie was deeply enamoured, too. Their conversation turned easy and intimate while Woodie’s buddies were still trying hard to impress the other girls. Later that afternoon, the group split up, and Woodie, though he’d known Lini for no more than a couple of hours at this point, didn’t see any point in wasting time. He brought Lini to Wyoming Island for the litmus test.

She liked it from the outset. “I thought this whole place was really beautiful. And his father liked me right away because I paid attention to the stuff on the walls.” She also got her first taste of the Stevens’ unique, homemade family cottage chairs on the stone deck and made a point of saying how comfortable they were. “I asked about everything and told him how wonderful it all was, and I meant it.”

Lini and Woodie spent a week at the cottage alone later that summer. Within five months, Woodie had achieved the following milestones: he proposed, he and Lini were engaged and then married, and Woodie built Lini her own rock chair.

When Lini gushed to her future father-in-law about the family cottage, it was no small compliment. The walls of the Stevens family cottage are replete with built-in shelves, hooks, mantels and plate rails, the better to festoon them with tchotchkes and quirky artifacts. It’s a living family archive that puts their values on display.

And it’s a display so rich that it’s actually hard to see the walls themselves. Toby jugs. Commemorative plates. Family photographs. Model boats. Muskie mounts. Busts of ship captains. Two American flags in triangle fold—tributes to relations killed in war. A ship’s wheel. Regatta silverware galore, from medals to banners to plaques. Beer steins. Family sayings and poems.

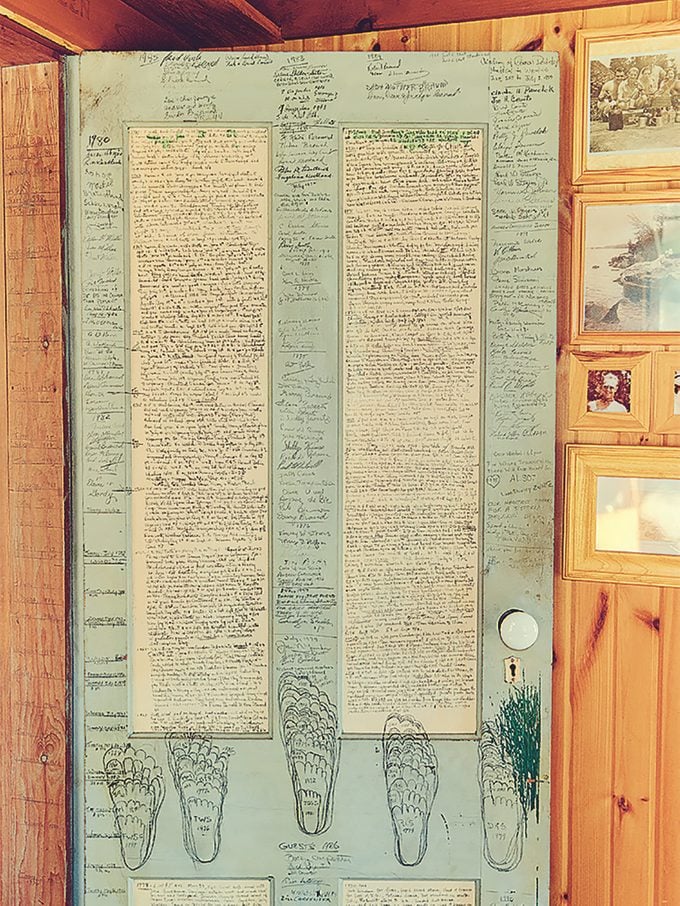

What Lini noticed in particular—what everyone notices—was the bedroom door off the dining area that doubles as a logbook. It’s a beautiful old door, solid wood with four recessed interior panels. Every inch of that door—the panels, the borders, top to bottom—has a log entry inscribed into it. One side of the door, unpainted, covers the period ranging from the interwar years to the 1960s. The other side of the door, painted blue and white some 50 years ago and never to be repainted, contains entries running from 1971 to the 1990s, when they ran out of room.

The door looks better than it reads—if you parse the Stevens’ door log, you’ll learn that they got a new dishwasher and electric range in 1972; you’ll read about water levels and first swims and first paddles; you’ll find the names of dinner guests; and you’ll see the outlines of their kids’ feet, showing how they’ve grown over the years. But cottage logbooks aren’t meant to be great literature. They are meant to mark the passage of time in a place where time stands still. No one bothers keeping a logbook of their city home; we buy and sell urban dwellings like the commodities they are, and whatever traces of ourselves we leave behind will be forgotten with the next reno. But our cottages are truly ours, and we make our mark indelible upon them.

When Woodie’s dad first told him to be quiet and listen to the river, it felt to Woodie as though his dad was passing on a piece of wisdom he’d always known, a lesson he always knew his son had to learn and that he had just been waiting to impart to him when the time was right. But of course, that’s not true: his father was also a restless young man once, and he also had needed to learn to be still, as did his father, Junius. This is surely why Junius invented his own cottage chair.

Despite its rough appearance, the Stevens cottage chair is the most comfortable version of the Muskoka-Adirondack chair I’ve ever sat on. The angle of the seat is not as steep as in a true Muskoka chair, making it easier to get in and out. And your spine fits neatly into the space between the two backrest boards, allowing your shoulder blades to press flat against the backrest.

In the Stevens chair, you also sit a little taller, making it easier to converse with others, read or write in a notebook on the armrest. Or to simply look out over the horizon and listen for the river, and to feel its power, even when you’re not immersed in it. Island cottaging teaches you to step outside the current, watch its flow and not react, nor respond, nor go with the flow or against it. The only way to be still is to sit still.

Next, check out the story behind the fascinating origins of butter tarts.

© 2021, Philip Preville. From “A Family’s Homemade Chair Is More Than Just a Place to Site,” Cottage Life (August/September 2019), cottagelife.com