The invasive Burmese python

It is just past five in the afternoon and I am walking atop a levee in a gated-off section of the Everglades seldom visited by the public, some 60 kilometres west of Miami. The thick, humid air is swarming with buzzing, whining mosquitoes, black flies and other insects that I am constantly swatting away from my face and exposed skin. Millions of chirping, grunting pig frogs add to this rowdy outdoor symphony.

An occasional jet-black alligator splashes into the water from its perch on the levee as I walk by; others eye me suspiciously but stay put, soaking up the late afternoon sun. Majestic herons, egrets, anhinga and countless other water birds burst from slash pines, cypress, and mangrove trees and fly overhead.

The 6,216 square kilometres of the Everglades, known as “the river of grass,” stretches as far as I can see, dotted here and there with tree-filled islands, hillocks, and the sawgrass-heavy swamp. The scene is as awe-inspiringly beautiful as it is wild. And, as I will soon learn, it can be extremely dangerous.

I have come to southern Florida to see how licensed local snake hunters are helping the government cope with the recent explosion of invasive Burmese pythons that is wreaking havoc with the region’s wildlife by eating almost everything—from raccoons to squirrels to rabbits to foxes—in their path. Indeed, the New York Times has described these serpentine invaders as “the snake that’s eating Florida.”

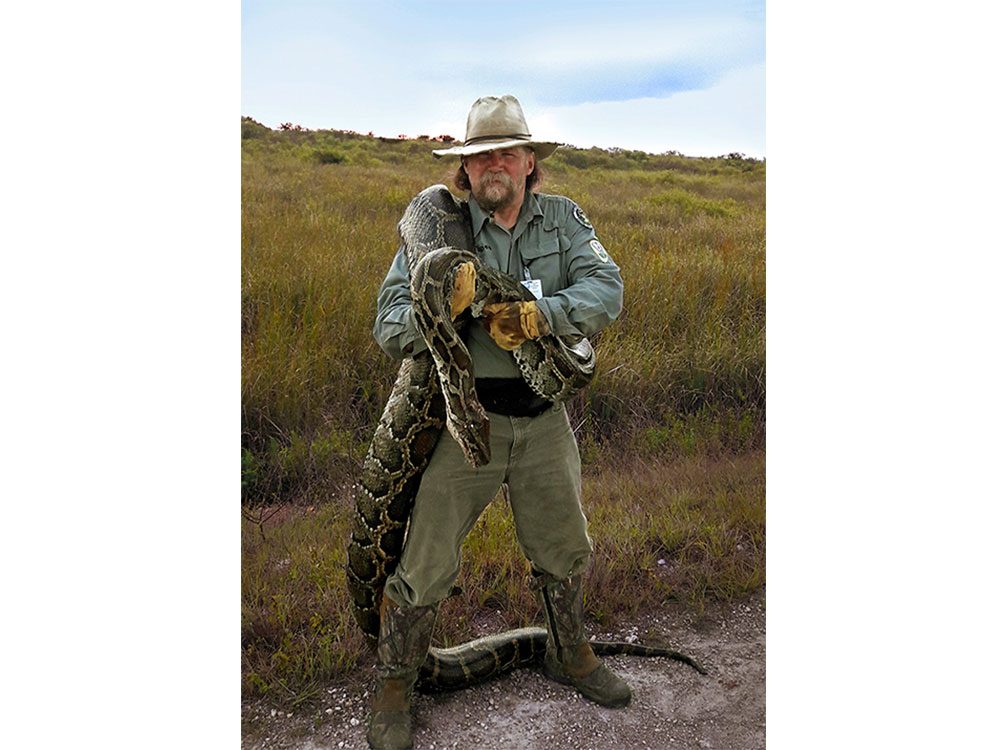

Thirty years ago there were no sightings of Burmese pythons in the Everglades, now most experts agree there may be as many as 100,000 to 200,000. And they’re reproducing at an alarming rate. In a last-ditch, government-sponsored effort to stem this invasion, the hunters are paid to catch and kill the powerful snakes, which can grow to be 20 feet long, as thick as a telephone pole and weigh over 200 pounds.

I am tagging along with Tom Rahill, a telecom technician by day and a python hunter on weeknights and weekends. He has caught over 500 of the snakes over the last decade and become known as “the snake whisperer” for his success. Rahill is also the founder of “Swamp Apes,” an all-volunteer group that takes military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder into the Everglades. “It’s a great way to get their minds off their troubles,” he explains.

As we walk along the levee I watch Rahill occasionally poke a five-foot-long forked wooden staff or “snake stick” into a thicket of dense grass on a hardwood hammock. He points to a flattened section and tells me, “This is prime Burmese python country. You can see where they’ve tunneled through the grass.”

As he looks for more telltale signs such as shed skin, he reminds me that the invasive pythons have quickly become the apex predator in the Everglades. “The local wildlife doesn’t stand a chance,” he says. “They’ve eaten nearly all the small mammals in the Glades and are now even attacking alligators. They are magnificent animals, but they don’t belong here.” Rahill, 61, pauses to mop his brow with a red bandana and adds, “This invasion has become a tragedy for the Everglades.”

Suddenly, Rahill stops in his tracks and starts sniffing the air. “Python poop is horribly acrid. Once you’ve smelled it you’ll never forget it,” he tells me with a broad smile. “It’s so easy to walk by them; pythons are perfectly camouflaged.” Within minutes he spots a recently-shed skin on the ground. “This was a big one. Maybe a 10-footer,” he says as he holds up the days-old translucent tunnel of shed skin. “I knew we were in the right place!”

While he continues searching and probing the brush, I begin poking my own snake stick into the dense undergrowth and limestone crevices. As I walk along the levee, carefully dodging the poisonwood bushes that can cause a nasty rash, I feel a hand on my shoulder and hear Rahill shout, “Stop! Watch out!”

I freeze in place and he points out a thick, triangle-headed water moccasin coiled up at the base of a Brazilian pepper tree just inches away from my boot and ready to strike. I hadn’t seen the four-foot long, highly venomous pit viper (also called a cottonmouth).

“If he’d bitten you,” says Rahill as I step away, “your snake hunting days would be over.” As rivulets of sweat run down my forehead, I make a mental note: From now on walk behind the snake whisperer. And pay attention.

Find out how scientists are trying to save North American bats from extinction.

The apex predator in the Everglades

To get the background of the python invasion, I earlier visited Frank Mazzotti, 69, a professor of wildlife ecology and conservation at the University of Florida. Mazzotti has researched invasive plant and animal species for four decades, including 12 years of studying invasive reptiles. As we sit in his sunny, fourth-floor office on the campus in Fort Lauderdale, I ask him how many pythons have established themselves in southern Florida and the Everglades.

“You’ve heard the figures, ‘anywhere from 30,000 to 200,000,’ haven’t you?” he asks me. “No one knows the exact numbers for sure, because pythons are so hard to spot.”

After a pause, he looks me straight in the eyes and says, “What we do know, however, is there are a lot of them!” He laughs and says, “And a lot is way too many!”

Many experts believe the python invasion of southern Florida began in the 1980s when python owners, possibly disenchanted with their fast-growing reptiles (hatchlings average 22 inches and can grow to ten feet long in less than two years), released them into the Everglades. “It’s likely that the owners didn’t want to kill them so they let them escape into the Everglades,” says Mazzotti. “Big mistake.”

Mazzotti and others also point to the pet trade as a likely origin of the invasion. They believe, given the snakes’ low level of genetic diversity, that they were either deliberately or accidentally released by reptile dealers decades ago. Some also claim that Hurricane Andrew in 1992 may have damaged breeding facilities, releasing the invasive reptiles into an ecosystem where they flourished.

However they got to southern Florida, the snakes have quickly become a dominating force. “They are perfectly suited to this habitat,” says Mazzotti. He explains that the Burmese pythons are both habitat and diet generalists. “That means, unlike many other species, they can easily change their diet to gobble up whatever is available.”

Mazzotti describes them as voracious eaters or “vacuum cleaners.” “And they are not overly picky about where they live.” Even worse news for their Florida-based prey: They are remarkably fertile. A female python can lay 50-100 eggs per season.

Burmese pythons are skilled ambush predators, preferring to lie in wait for their prey before striking out at them, grabbing them with their several rows of needle-sharp, backward-facing teeth and then coiling around their prey, constricting them until they stop breathing. How effective are they? A study showed that over the last two decades pythons were likely responsible for devouring all the rabbits and foxes in the Everglades, as well as more than 85 per cent of the region’s opossums, raccoons and bobcats.

Remarkably, by “shrinking” their vital organs and lowering their metabolism, they can also go without eating for as long as a year. And they are masters at camouflage; their brown and tan colouring helps them virtually disappear in the wild. Mazzotti recalls releasing a 14-foot female, which had been fitted with a transponder, back into the Everglades. “I was holding her by the tail but as soon as she slithered into the water, even though I still had hold of the back half of her, I could no longer see the front half of her. It was as if that half had suddenly vanished.”

Many python hunters have reported that the snakes are so well camouflaged that they haven’t found them until they have stepped on them. Says Mazzotti, “Imagine the perfect, apex hunter. Now imagine that hunter is wearing high-tech camouflage. They’re that good.”

Hunting for Burmese pythons

Before I leave Mazzotti’s office I ask him about the likelihood that this invasion can be stopped or reversed. “I think,” he says as he shakes his head, “we are about 10 years too late to make a difference. I am afraid the pythons are here to stay.”

I am reminded of Mazzotti’s “camouflage” quote after several days of bushwhacking through the Everglades with Tom Rahill and failing to spot a single python. We’ve walked along levees, alongside some of the hundreds of kilometres of canals managed by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD), and have slogged through the murky waters of the Everglades themselves. While we’ve seen many other snakes, from cottonmouths to racers to coral snakes to diamond back rattlers, and countless alligators, tortoises and water birds, we’ve yet to spot a Burmese python.

Tonight we’re taking a different approach; we will drive slowly along the canals in Rahill’s battered Chevy pickup truck in the hopes of spotting a Burmese python on the road or levee. As Rahill has told me, “Road cruising is a great way to spot pythons that have slithered out of the Everglades to warm themselves on the road surface.”

I meet Rahill near Kendall, Florida, some 24 kilometres southwest of Miami near the eastern border of the Everglades. He has outfitted his truck with powerful lights on both sides and the front to help us spot the snakes. The sun is close to setting and just before we unlock one of the water district’s gates to start our search, a local resident approaches us on horseback.

Nicky Garcia, a 66-year-old with a weather-beaten face and a welcoming smile, introduces himself and tells us he has owned his home in the Rocky Glades area of the Everglades for 30 years. When he learns we are hunting for Burmese pythons he reaches down to shake our hands.

“Thank you,” he says. “They got a lot of my animals!” Over the years, he has lost more than 60 chickens and at least five goats to pythons.

“Go get them. Please,” he says before he rides off.

As we drive alongside a canal with our spotlights shining brightly from both sides of Rahill’s pickup, he reminds me what I should be looking for. “A python on the road in front of us is easy to spot; it will look like a speed bump,” he explains. “But as you look down the levee and into the Everglades you’re looking for anything that doesn’t seem to belong; anything out of the ordinary.”

“If we see a big one, you’ll have to grab the back end of it while I go for the head. Think you can handle that?” he asks me.

“Sure,” I lie.

“Great. One other thing. More than likely it will poop all over you.”

Now is not the time for second thoughts, but I suddenly recall a recent story about a 25-year-old Indonesian villager who recently went missing on a palm oil plantation. A day later he was discovered inside a giant 23-foot Burmese python that had killed him and swallowed him whole. In Florida in 2009, an eight-foot pet python killed a two-year-old girl. But I remind myself that python attacks on humans are rare.

It’s dark now, the moon is full, and it’s as if we are driving through a tunnel of light. Rahill is scanning the levee while telling me “war stories” about past captures he has made. He describes the time he spotted a 12-footer as it was slithering down the levee and into the Everglades. “The minute I saw it, I slammed on the brakes, scrambled down the levee and grabbed it by its tail just before it got into the water. It was incredibly strong and I was alone,” he says. “Somehow, after wrestling with it for more than ten minutes, I got it back onto dry land and managed to overpower it and pack it into an oversize pillow case. I was sore for a week.”

Another time he spotted a massive python that had just slithered into the water. He and a friend grabbed it by the tail but the snake was so strong it dragged them both 60 feet into the water and swam away. “It pulled us along like we were feathers on a freight train,” he remembers. “Frightening.”

Just then, as if on cue, Rahill turns onto another levee and suddenly shouts, “SNAKE!” There, slowly crossing the levee’s crushed limestone road, is a Burmese python. He slams on the brakes, whips open his door and rushes to the snake. It looks like a five to six footer (“a teenager but a strong one,” shouts Rahill). Its thick, full belly indicates it must have killed and eaten recently.

Expertly, Rahill bobs and weaves, dancing around the snake as it strikes out at him. He then grabs it with one hand firmly behind its head.

“Grab the tail,” he tells me.

As Rahill holds the head of the snake I grip its tail and am amazed as I feel what seems to be solid muscle while it fights to get free. I tighten my grip as the snake tries to wrestle itself away from me and coil itself around my arm. Then, just as Rahill predicted, it poops all over me.

My pants are covered with white blobs of Burmese python poop with a stinky, sulfurous musk. But I don’t care. We’ve finally bagged our python. Rahill and I high-five each other. Later he will kill the snake and turn it in to SFWMD for payment—nearly $100 for one of this size. Although it’s just after three in the morning, he asks me if I want to keep hunting. I quickly tell him, “Let’s go!” As Frank Mazzotti said, there are a lot more pythons out there.

Next, learn about seven animals that are deadlier than sharks.

Editor’s Note: The South Florida Water Management District recently announced that licensed hunters had captured and killed the 1000th Burmese python under its Python Elimination Program, which began in March 2017. More recently, after resisting for years, the Everglades National Park has opened its lands to authorized python hunters.