The freak accident

The snow began to fall earlier than they’d expected, but Jeremy Osheim wasn’t worried. He’d driven this route a thousand times, and he knew exactly what to do. Take it easy. Watch the road. You’ll get there when you get there, and when you do, it’s going to be awesome.

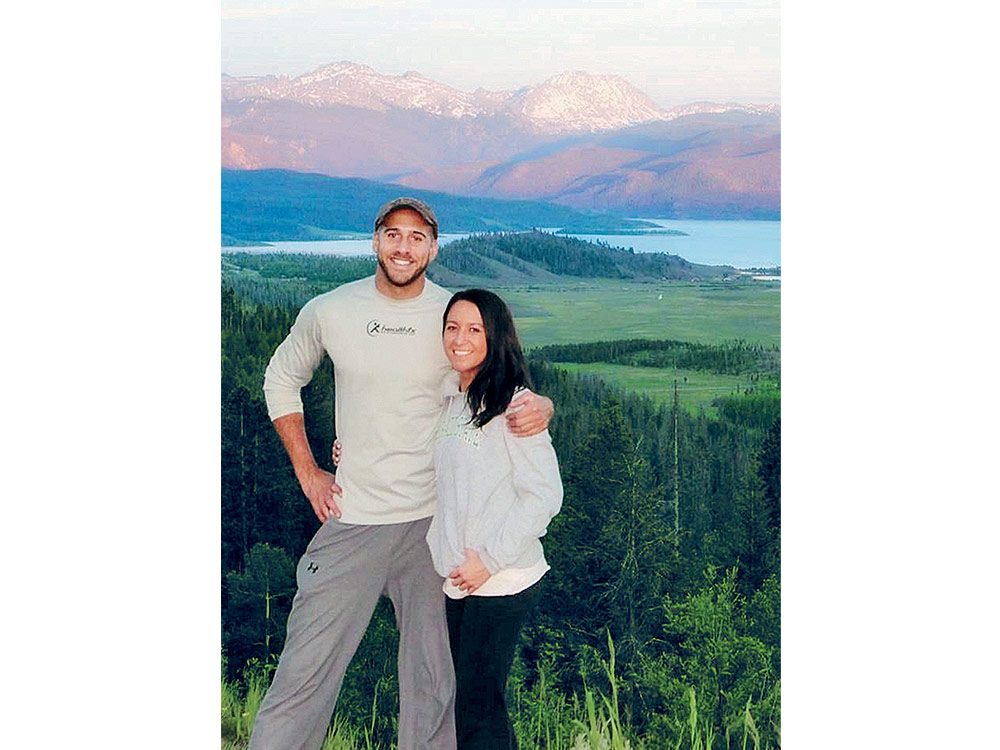

It was January 30, 2016, and Osheim and his girlfriend, Molei Wright, were leaving Denver for a weekend on the slopes in Breckenridge, Colorado. The pair were like-minded: ambitious, gregarious and thoughtful. Both had grown up in Colorado and were lovers of books, plays, music and the outdoors. Osheim, then 29, was a PR specialist who moonlighted as a mixed martial arts fighter; Wright, then 28, was the first in her family to graduate from college and worked selling mutual funds to financial advisers. They’d been together for less than a year, but it had taken only a few dates to realize they clicked. They’d never formally said, “I love you,” to each other, but Osheim was pretty sure Wright was the one. As the car turned and climbed along the road, Osheim felt an overwhelming wave of gratitude.

“That was probably the best moment of my life, just feeling so good about what was ahead for us,” he says. “Then, within a blink of an eye, everything was shattered.”

The freight truck that hit them came out of nowhere. One minute, Osheim was driving his SUV smoothly through the falling snow; the next, he was sitting by the side of the road in a mangled vehicle, pinned to his seat by the steering wheel, his body screaming with pain. Next to him he saw Wright. Her eyes were open, but Osheim could tell they saw nothing. All he could think to say: “Don’t die. I love you. Don’t die…”

Statistically, Wright should have died. Inside her neck, the vertebrae had been crushed. Her head was attached to her shoulders by nothing but skin and muscle. Doctors call it cervical occipital dislocation. The more common description is internal decapitation. The odds of survival: one in 100.

Henry Rodriquez, a vacationing army lieutenant trained in emergency medicine, was driving on the same highway not far behind the SUV, and when he saw the wreck he pulled over instantly.

While his wife, Brittany, calmed the trapped and terrified Osheim, Rodriquez worked swiftly. One wrong move and Wright could be dead or paralyzed. Protecting her head and neck, he carefully extracted her from the twisted wreckage and laid her on the road by the side of the car, keeping her warm by covering her with coats that Brittany had collected from other drivers.

For 45 harrowing minutes, Rodriquez pounded her chest to bring her heart back to life. As the ambulance rushed to the scene, she showed flickers of consciousness and movement, but eventually those hopeful signs were gone. That she made it alive to Lakewood’s St. Anthony Hospital, about 45 minutes away, was a miracle.

Brush up on the seven essential steps of CPR.

The fight to stay alive

By the time Wright’s mother, Mo, finally arrived at around 11:30 p.m., Wright had sunk into a coma and was hooked up to a half-dozen tubes and machines. The doctors could tell Mo almost nothing beyond the obvious: Wright’s injuries were extremely serious. At a moment’s notice, fever or infection could carry her daughter off. And even if Wright’s body stabilized, her brain might never recover.

“One doctor took me aside and said, ‘I need to be honest. There’s a chance she’s not going to make it,’” says Mo. “And I remember saying, ‘Molei is a fighter. She’s competitive. She’s not one to just lie back and take this.’”

But doctors knew it might not be up to Wright. In addition to her shattered neck, Wright had suffered fractures to her ribs and other vertebrae, bruises on her lungs and damage to the major arteries bringing blood to her brain. Scans showed hemorrhages all across her brain’s surface, blood vessels and stem.

Like anyone who has suffered a traumatic brain injury, Wright’s chances of recovering consciousness had entered a realm of mystery. How well a particular mind returns is completely unpredictable. In fact, doctors have a saying: If you’ve seen one brain injury, you’ve seen one brain injury. Sometimes victims come back fully capable and healthy. Sometimes they linger indefinitely in a state of unconsciousness.

Sometimes, patients’ brains survive but their personalities don’t. “They get angry, they have temper problems, their families are afraid to be around them,” says Dr. Philip Yarnell, a trauma neurologist who treated Wright. Such cases can be devastating, shattering relationships and ending marriages. “You’re with one person and then you’re with another, and it’s not the one you started with.”

Yarnell knew that, as soon as they arrived at the hospital, the Wright family would want answers. But they’d have to wait. “[Doctors] don’t give a long-term prognosis,” he says. “You can be fooled.”

So as Wright lay silent and still, the best the doctors could do to save her brain was to save her body by using drugs to fend off fevers and infections. Machines for food and oxygen. Surgeries for injuries. Constant monitoring for signs of consciousness. And above all, patience.

In the weeks following the crash, a pattern set in. Wright lay in her bed being fed through a tube, breathing on a ventilator. Yarnell and his team would come in every day to test her reactions and see whether her brain was responding: poke her arms and feet; pinch her shoulders; move objects in front of her face to see whether her eyes would track them.

But as the doctor’s log documented, Wright showed no response.

February 6: Not following commands.

February 11: Not following commands.

February 15: Not following commands.

“It was killing us,” Mo says. “Every morning I’d get in the car and drive to the hospital, and every morning was my lowest moment. What are they going to tell us?”

Osheim, who was still recovering from his own injuries (a broken hip and scapula, as well as heart and lung contusions), followed the nurses’ cues and talked to Wright as if she could hear him.

“I just kept thinking: She’s going to come back to me. I know it,” he says.

But Osheim also knew that Wright’s chances of recovery were growing slimmer over time. At one point, her wrists and hands started to curl inward, a phenomenon called posturing that can indicate irreversible limb damage. “I was heartbroken,” says Osheim.

And then, about three weeks after the crash, Wright began to show signs of recovery.

February 25: Able to move the right leg spontaneously.

February 29: A focused gaze.

March 1: Off the ventilator all day. Looks to both sides.

The signs of progress came slowly, but they were enough. Somebody was in there.

Wright can still remember seeing the date on the whiteboard at the foot of her bed and realizing that three full months of her life had disappeared.

“It said, ‘Hello, Molei! Today is Wednesday, May 18,’” she says. “It was confusing…like, Wait! What happened to February and March and April?”

Wright didn’t yet know it, but she was now in Craig Hospital in Englewood, Colorado, one of the nation’s leading rehabilitation centres for brain and spinal injuries. Three months after the crash, when Wright was well enough to be moved, Yarnell had her admitted there. At the hospital, staff worked to revive her with regimens of wake-up drugs and physical therapy.

After coming to, Wright was largely in a fog for the first several weeks. She understood who she was, but she couldn’t connect with nurses, doctors or even loved ones. She didn’t know whether she ever would.

And then one day, around late May, Osheim made her laugh. It happened in the workout room at Craig. By this point, Wright was in limbo, halfconscious. She couldn’t direct her own movements or talk. But if Osheim or her therapists moved her limbs, she could sit up and even stand.

That day, Osheim was doing just what he’d been doing for weeks: helping and hoping. First, he hoisted her from the bed and onto a kind of hanging chair that moved on tracks, which in turn took her to a wheelchair. From there, he guided her down to a room full of padded platforms designed for massage and therapy. His plan was to stretch her limbs a bit while he talked to her. So he laid her on the therapy bed, sat at her feet and started flexing her legs, chattering and spouting nonsense, as he called it, just as he’d been doing for months.

He wasn’t surprised when Wright’s body suddenly spasmed and she sat up abruptly. Without even thinking, Osheim responded, “Hey, we’re not doing sit-ups. What are you doing?” And she laughed.

Suddenly, Osheim’s eyes lit up. “Oh my God!” he shouted. “You hear me! You’re in there!”

It was a watershed moment. “I don’t know if I’ve ever laughed so much or smiled so hard,” he says. “I knew then that she still thought my stupid jokes were funny. She knew who I was.”

It was a breakthrough for Wright as well. “He could tell, ‘Hey, I’m still in here! I’m not just this girl in a coma,’” she says.

In the weeks that followed, Wright improved dramatically. Soon she was watching, listening, focusing and responding. She still couldn’t talk, so she tried to communicate using the sign language she’d learned in college. Osheim knew some sign language, too, so he understood the first thing she told him.

“It was, ‘I love you,’” Wright said. “That’s the first thing I said to him.”

The return home

Wright had spent a total of six months in hospital after the crash, including two months at Craig, where she learned to eat carefully, talk slowly and travel short distances with a walker. The cognitive rehabilitation therapy, including puzzles, tests and medication for focus and attention, had started to repair her mind. The brain is a remarkable thing, Yarnell says. If you keep exercising it, it can find ways to work around its problems.

When the doctors said she was ready, Wright moved back into her family’s home. There were setbacks and frustrations; the simplest decision, such as whether to rely on the walker or the wheelchair to get to the living room, could be fraught. But every month, Wright made progress. And eventually, everyday tasks became routine: using the bathroom, folding laundry, riding the exercise bike. As her body revived, her mind sharpened, just as Yarnell had predicted.

In what may have been her biggest step of all, Wright moved in with Osheim 18 months after the crash. The life they’d once imagined sharing began to take shape. And even if it isn’t exactly the life they’d expected, Osheim says, the love they share is just as deep—maybe deeper.

“I liken it to going to war with someone,” says Osheim. “We went through something that is unfathomable to other people. I shared some things with her that I can’t quite explain.”

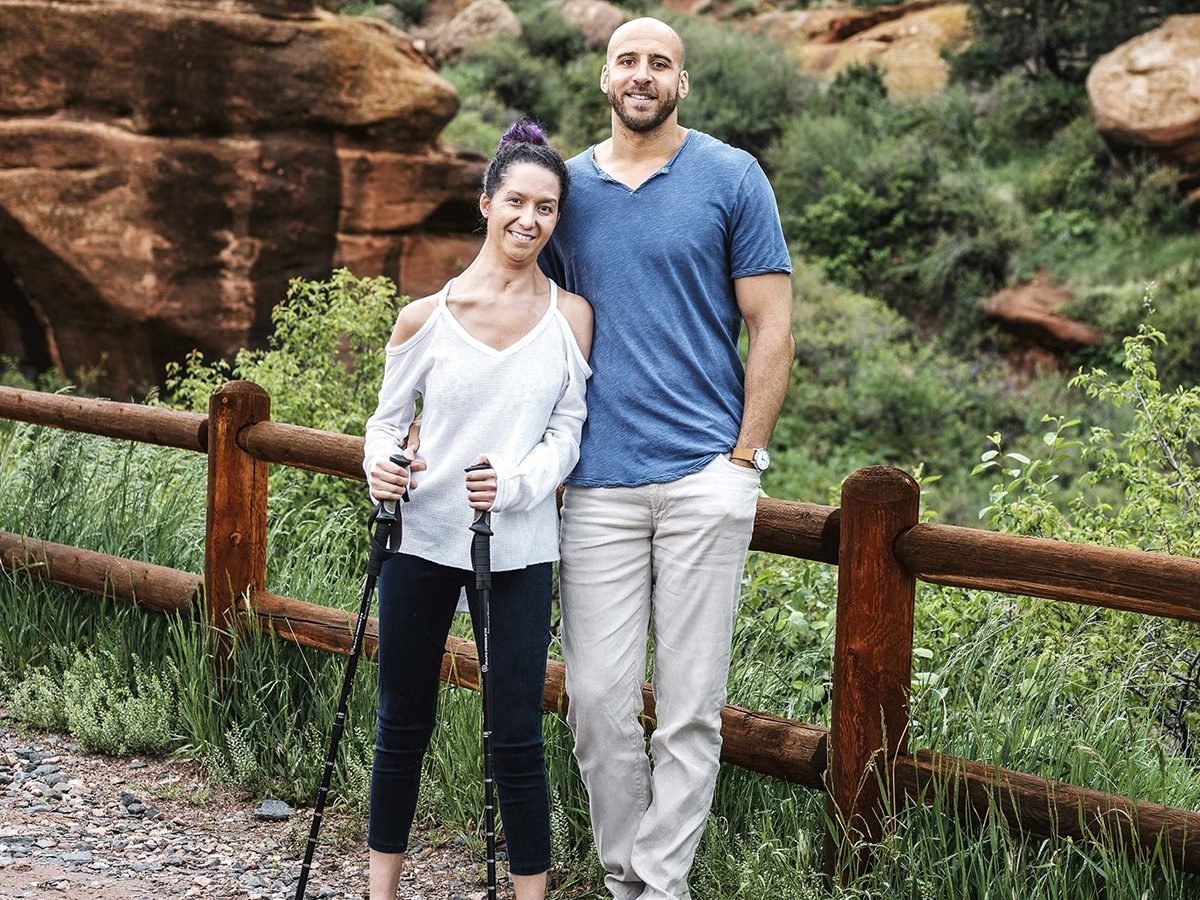

Today, Wright still faces a series of challenges. Her left side remains weak, her grip uncertain and her fused spine means she can’t turn her neck. Yarnell says Wright will probably always have some cognitive deficits. Multi-tasking will likely tire her out. Holding down a high-stress job might never be possible.

And yet, she manages the couple’s household along with her own recovery. She meets with friends, shares books and podcasts with Osheim, and volunteers to visit classrooms and talk to students about what her experience taught her about perseverance and kindness. She’s training for a bike race and considering a new career as an occupational therapist.

She’s the Molei whom Osheim fell in love with, the one who’d never settle for anything less than the best. “You just can’t turn off this wild ambition,” he says. “You can’t go through something like this and be exactly the same person, but the core of who she is remains the same.”

In February 2018, two years after she and Osheim almost died on the way to Breckenridge, Wright finally arrived at the resort town. With the assistance of outriggers—poles with mini skis attached to their base—she glided down the mountain on adaptive skis, plowing through the snow as the trees blurred beside her and her cheeks tingled in the crisp air.

She wasn’t a crash victim anymore. She was just Molei Wright, out in the sun with the man she loved, conquering the mountain she’d first set out to run two years earlier.

“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is happening!’” Wright remembers. “It was liberating.”

Check out more gripping stories from Reader’s Digest‘s Drama in Real Life.