Why I Already Miss Le Château

The closing of the iconic Canadian brand—which defined fun fashion since the 1960s—leaves a triangle-sized hole in our malls.

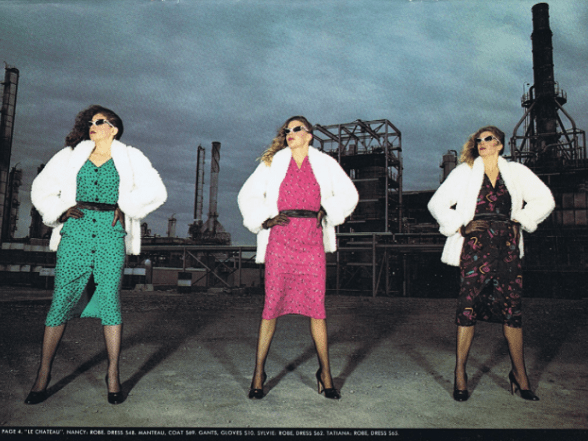

Growing up, Le Château was always the “prom store.” When news broke that the Montreal-based retailer had filed for court protection from creditors and would be liquidating all 123 of its stores, countless Canadians of a certain age—namely, millennials 30 and above—shared memories of two-tone organza spaghetti strap dresses and midriff-baring one-shoulder tops. In its late ‘90s–early 2000s heyday, Le Château was a veritable bastion of slinky lurex dresses and “going out tops”—flimsy pieces of fabric held together by pieces of string. The brand’s clothes were ostensibly aimed at people above legal drinking age, but also somehow ended up worn by preteens with a 9 p.m. bedtime. I vividly remember experiencing my first whiff of independence after being dropped off with a friend to walk unsupervised around the Quinte Mall in Belleville, Ont., where we would make a beeline towards Le Château to gently caress racks of flared polyester pants that laced up on the side and dream of the people we would someday become.

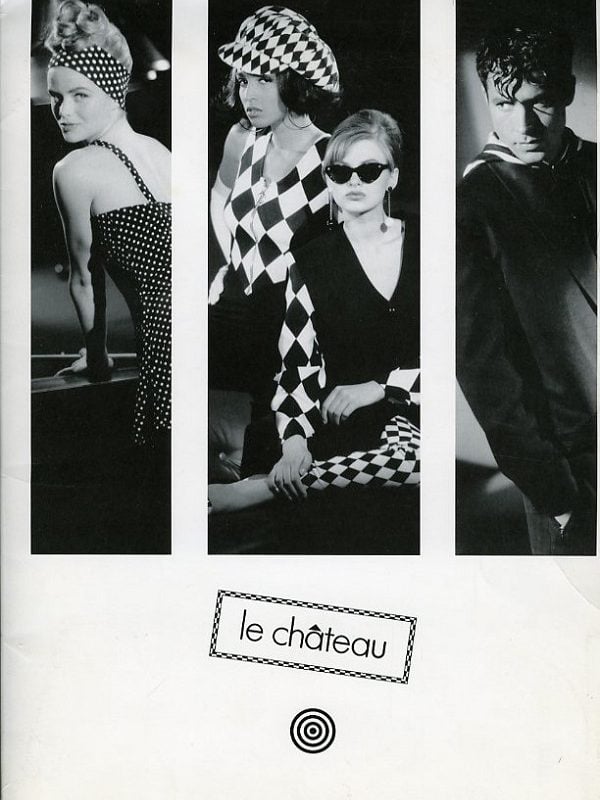

Now Le Château now joins Cotton Ginny and Zellers in the retail graveyard of once-beloved Canadian stores that, sadly, just weren’t able to make it work. Founded in 1959 by Montreal fashion retailer Herschel Segal, Le Château initially sold discounted overstock clothing before it became the centre of Canada’s 1960’s youthquake. Segal introduced European styles to a fashion-forward crowd and has claimed to be the first person to introduce bell bottom pants in Canada. John Lennon and Yoko Ono donned Le Château black velour tracksuits for their 1969 Montreal bed-in for peace—the ultimate coup in cool.

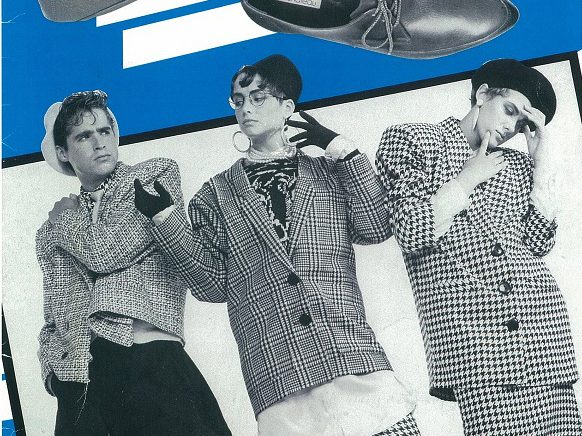

By the 1980s, the brand had rebranded as a mall staple and became what was essentially a progenitor of H&M and Zara: an emporium of hyper-trendy, disposable clothing available at a mid-range price. But what set Le Château apart from its global competitors was its longstanding commitment to Canadian manufacturing. Le Château was one of the few remaining fashion brands that continued to produce a portion of their offerings in Canada—a stalwart holdout of Montreal’s once-booming garment district.

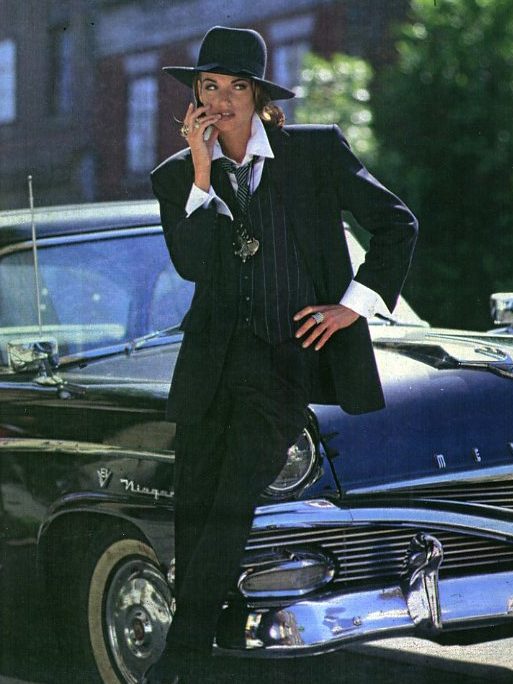

But in recent years, Le Château’s often-flimsy clubwear failed to attract the cool teens it had once effortlessly catered to. While working as a fashion editor, I recall being invited to the Eaton Centre for a sneak-peek at the season’s new offerings. The fluorescent-lit store was packed tight with tailored blazers and boot cut pants made out of borderline flammable material, slouchy camel coats and bridesmaids dresses. Yet despite the literal cornucopia of stuff, I couldn’t find a single item of clothing I wanted to wear. I left the store empty-handed.

In the end, Le Château was a victim of the pandemic (it’s owners cited Canadians’ changing shopping habits, especially the drop in demand for prom wear) as well as its own pragmatism. By manufacturing milquetoast work clothes for a nebulous demographic of “young professionals,” Le Château lost the elusive aspirational quality that remains key to maintaining a successful fashion brand. Had they shifted gears and attempted to target a specific customer—early 2000s nostalgia-core, loose flowy linens, or even athleisure bae—they might have stood a chance at recapturing the zeitgeist. In their efforts to cater to everyone at once, they ended up appealing to no one at all.

I wish Le Château’s dedication to Canadian manufacturing had been enough to save it. The company has skirted death before. Segal first went bankrupt in the early 1960s, and was close to shuttering the company in the late ‘90s, early 2000s and early 2010s. Still, something about Le Château felt permanent. I took it for granted that Le Château would emerge out of this difficult period unscathed, just as they had the previous 60 years.